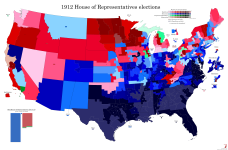

I'm very glad this latest change in theme seems to have brought some interest, because there's more congressional maps coming.

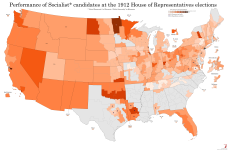

We start this series in 1912, an interesting year for a number of reasons. Firstly because it was the last really properly three-cornered presidential race in U.S. history - in 1968, while Wallace ran a nationwide campaign with a nationwide party, he got very limited traction outside the South and even he would probably have candidly admitted that he wasn't trying to win the presidency outright, and in 1992, Perot got a reasonably impressive nationwide voteshare but won no states and wasn't really close to winning more than a handful of electoral votes. In 1912, however, there were three candidates heading nationwide organised political parties who all had significant pockets of strength around the country, although it was pretty clear from the beginning who was going to win.

The Progressive Era, which was at or near its absolute zenith in 1912, was a weird period in American political history. Generally, most American party systems consist of one "active" political party, whose formation or adoption of a new program signals the start of the party system, and a "reactive" party, who form as a broad coalition in opposition to the active party and tend to be a lot less ideologically coherent. From 1860 until about 1890, the Republicans had been the active party in American politics, formed on a platform of opposition to slavery, American nationalism and an economic policy that combined government aid for economic development (particularly rural economic development) with protectionist trade policy and strong support for big business, and gathering a coherent bloc made up of businessmen, small-town notables, farmers and Protestant churches. Opposing them were the Democrats, left over from the previous party system, and combining their old Jacksonian populist element with urban machines, Catholics and immigrants as well as the white supremacist bloc in the South, which by 1890 was completely and utterly dominant across most of the region. It was an extremely weird amalgam of interests, but through most of the period, control was maintained by a pro-business faction known as the Bourbon Democrats, who ensured that the party mostly differed from the Republicans in wanting lower tariffs and a weaker federal government. The main divide among voters had less to do with ideology and more to do with the legacy of the Civil War - if you or your family fought for the Union or otherwise identified with its cause, you probably voted Republican, and if you didn't (whether that was because you disagreed with Lincoln's conduct in office, because you were on the Confederate side, or because you came to America after 1865 and didn't have a stake in the matter), you probably voted Democratic.

By the 1890s, however, things were slipping. Grover Cleveland's presidency, usually regarded as the peak of the Bourbon Democrats, resulted in new battle lines being drawn, with a number of anti-corruption Republicans breaking with the party to support Cleveland against James G. Blaine, who was widely suspected of having sold favours to railroads during his time as Speaker of the House. On the Democratic side, meanwhile, Cleveland's conservatism drew the ire of the populist wing of the party, and after the Panic of 1893, his critics were able to take full control of the party. The 1896 DNC, dominated by southern and western anti-Bourbon interests, resulted in the nomination of William Jennings Bryan, a young firebrand from Nebraska who seemed to run against everything Cleveland stood for. The nascent People's Party, an organisation of farmers and rural workers in the West who had won a few electoral votes in 1892 and had a decent-sized bloc of seats in the House of Representatives, cross-endorsed Bryan, and the stage seemed set for a new realignment along something more like what we might recognise today as left-right lines.

Yet this never happened. Perhaps it was too early in 1896, a time when many thousands of Civil War veterans were still alive and the legacy of the conflict still shaped politics, for the political divide created by it to simply go away. Regardless, the Democrats and Republicans continued to operate, and indeed still continue to operate to this day. Bryan's crusade against the bankers and plutocrats who would "crucify mankind upon a cross of gold" did not convert the Democratic Party into a vehicle for progressive reform, and indeed conflict would continue to rage between his faction and the legacy Bourbons right up until FDR forced them together to combat the Great Depression.

Instead, the Progressive Era would come to be defined by these internecine struggles between progressive and conservative forces within each party, and it was a Republican who would implement most of the key progressive demands. In 1900, as William McKinley ran for re-election, he was persuaded to accept Governor of New York, and leading progressive Republican, Theodore Roosevelt as his running made. This was done partly as a sop to progressives within his own party, partly to neutralise Bryan's message in his second run for the presidency, and partly because the New York Republican machine wanted to neutralise Roosevelt by kicking him upstairs to a largely-powerless federal office. This backfired spectacularly the next year, when McKinley was assassinated while visiting the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, and Roosevelt assumed the presidency. He would serve for almost two full terms, winning re-election in 1904 and retiring in 1908, handing power to his hand-picked successor William Howard Taft.

Taft would go on to alienate Roosevelt and his progressive faction in office. There's been raucous historical debate over how much of a conservative Taft actually was - he continued many of Roosevelt's initiatives, and would later argue he'd gone further to break up trusts than Roosevelt had. According to this line of argument, Roosevelt moved to the left after his presidency, arguing for a "New Nationalism" which included things like social insurance, inheritance taxes, an expanded right to strike and campaign finance regulations, and while Taft continued to implement the agenda of Roosevelt's presidency, he did not support his mentor's new tack. According to Roosevelt's supporters, meanwhile, Taft had been captured by big business and was now a full-throated enemy of their movement. Wherever the truth lay - and there was probably some truth to both sides of the argument - Taft and Roosevelt became the standard-bearers for the opposing factions of the Republican Party heading into the 1912 election.

It pretty quickly became clear that the Republican state organisations mostly favoured Taft's more moderate line, and that the convention would be dominated by the conservative faction. Roosevelt's supporters blamed this on the large Southern contingent at the convention, which was both firmly conservative and hugely overrepresented relative to the number of Republican voters in those states. Disputes over this led most Roosevelt supporters to abstain on the nomination ballot, and when Taft won the nomination on the first ballot, they walked out of the convention. They hastily organised a convention for a new "Progressive Party", which nominated Roosevelt unanimously and approved a platform, the "Contract with the People", which essentially copied Roosevelt's "New Nationalist" agenda. There was one notable exception - antitrust measures, which had probably been the single most important progressive hallmark of Roosevelt's presidency, was struck from the platform in favour of vague language about "strong regulation". This was blamed on the influence of George Walbridge Perkins, one of the party's key financiers and an employee of J. P. Morgan whose progressivism included arguments for "the Good Trust", and a number of leading progressives declared the new party a lost cause before it really got going.

Nevertheless, Roosevelt was still personally popular, and a large number of rank-and-file Republicans defected to his campaign, giving him a momentum that easily overpowered Taft's official Republican campaign. Whatever Taft's personal politics might have been, the formation of the Progressive Party left the GOP firmly in conservative hands, and its campaign focused on attacking Roosevelt as a dangerous radical who would change America beyond all recognition and/or an inveterate egotist who was only running to satisfy his vanity and sabotage Taft. It wasn't a very effective strategy, and Taft, as the only status quo candidate in the race, had very few real arguments to sway voters.

But, of course, there was also a Democratic campaign. And surprisingly enough, even as the Republicans were tearing themselves apart, the Democrats appeared more united than ever. There had been a clamour for Bryan to run again - his fourth heave - but the man himself refused, believing the one thing that could hurt the party's chances at this point would be nominating a three-time loser. This meant a bitterly contested convention, a Democratic Party tradition in the making, which ended up nominating Woodrow Wilson, a southerner who moved to New Jersey to take up a professorship at Princeton University - he'd served both as president of the university and governor of the state by the time of his nomination. Wilson was known as a reformer who took an intellectual approach to politics and shared many progressive goals, but he also appealed to conservatives in the South because he came from there and remained outrageously racist even by the standards of the time. As President, even as his administration made strides on some progressive issues, the federal government was segregated, and the Southern tradition of lynchings and race riots spread throughout the United States with the apparent blessing of the White House.

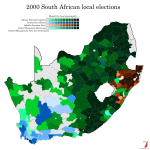

Because, in case you hadn't already figured it out, the main effect of the Republican split was to give Wilson a clear run for the White House. He won 40 of 48 states and 435 electoral votes, the largest number ever recorded, despite only gaining some 41% of the popular vote. Roosevelt won another six states, mostly in the West but also including Michigan and Pennsylvania, while Taft won only Vermont and Utah.

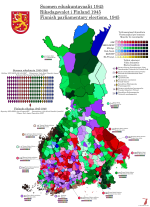

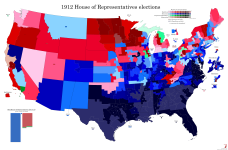

Of course, the map I've made isn't of the presidential election - you can find good maps of that in other places already - but of the congressional election that accompanied it. By 1912, all states elected their congressmen on the same day they elected the President, except Vermont and Maine, which elected their ones alongside state elections in September. This is the origin of the saying that "as Maine goes, so goes the nation" - it wasn't that Maine's election results tended to match those across the country, it was that you could read political trends from their elections because they literally voted two months before everyone else.

1912 was the first election after the 1910 Census, and also the first after Arizona and New Mexico were admitted to the Union. The Census showed a population of 92 million, up from 76 million in 1900, and the Apportionment Act of 1911 determined that 435 seats in the House of Representatives would be adequate to represent this population. For reasons we'll no doubt get to, this is still the size of the House, even though the country has more than tripled in population since then. Anyway, this represented an increase of 44 seats from the previous election, or 41 counting the three seats given to Arizona and New Mexico in the interim, and with around 210,000 inhabitants per seat, it still represented the largest population-to-seat ratio in U.S. history up until that point. Of course, while the states were technically required to make their electoral districts compact, contiguous and equal, in practice these rules were very loosely observed in a time before the Voting Rights Act.

This would be demonstrated in more ways than one. While, again, states were required by the Apportionment Act to draw as many districts as it had representatives, the Act also allowed for representatives to be elected at-large (that is, by the entire population of the state) as needed until redistricting laws could be passed. An astonishing fourteen states did this, with Montana, Idaho and Utah electing their two-seat delegations statewide, while another eleven states used a combination of statewide and district elections. Most egregious in this regard were Oklahoma, which gained three new seats but kept using its five districts drawn in 1906, and Pennsylvania, which gained four seats but kept using its 32 previous districts. Even more astonishingly, Pennsylvania would keep doing this for

ten years.

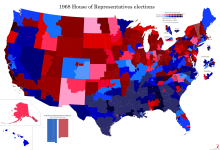

As with the presidential race, the congressional elections of 1912 were a blowout for the Democrats. Even though the House grew by 41 seats, the Republicans suffered a net loss of 28, and the Democrats won a two-thirds majority of seats. Their gains included inroads into strongly Republican regions like Pennsylvania, northern Illinois and rural New England, as well as commanding majorities in their Southern stronghold, which was by now thoroughly established as the "Solid South" with unopposed or nigh-unopposed elections as the norm. All that said, however, the Republicans still fared better than they did on the presidential level - even if many of their supporters backed and campaigned for Roosevelt's presidential campaign, there were only a few cases where the Progressives were able to get any sort of coattails. Usually, this involved incumbent Republican congressmen defecting to the party, and that was quite a rare thing even for more progressive-minded ones. Most of the Republican Party on the state and local levels stayed intact through the split, and in the end the Progressives were only able to win nine seats in the House - substantially less than the 22 seats the Populists had at their peak. Their delegation would only dwindle in size from here, further contributing to the party's image as a flash in the pan that had no basis for existing outside of Roosevelt's campaign. And in spite of future attempts to break the two-party system, the Democrats and Republicans continue to dominate U.S. politics to this day.