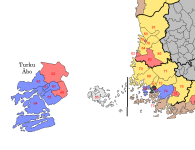

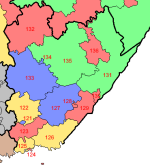

The ride goes on. I'm hoping to finish the map today, remains to be seen whether I can get the writeups done as well.

Finland Proper (18 constituencies, quota 20,911)

60: Turku Cathedral (

Turun tuomiokirkko,

Åbo domkyrka)

24,065 (+3,154)

I've had a casual look at Turku's ecclesiastical division while drawing these constituencies, and although I've ignored the parish boundaries in a lot of cases, it still felt right to name this seat, which covers the city centre east of the Aura river as well as the university area, after Finland's primate church. As a student-heavy area, it's generally pretty strong for the combined left, but its left-wing vote was heavily split between Left and SDP in this election, and as a result the seat went to the Coalition.

61: Turku-Mikael (

Åbo-Mikaels)

18,698 (-2,213)

Another seat named for a church, although in this case I believe the majority of the constituency is actually in the cathedral parish. This is the commercial centre of the city, but the newer side, having mostly been built during the Russian period and after the 1827 fire. Its politics aren't much to write home about, you should know the drill by now - safe Coalition. My guess is that Petteri Orpo would represent either this seat or #64, since he's not from anywhere in the city originally and those are the safest Coalition seats in it.

62: Turku-Maaria (

Åbo-Marie)

21,025 (+114)

Maaria used to be one of the two rural parishes covering the area around Turku, along with Kaarina south of the river. Today, it's thoroughly suburbanised and somewhat politically mixed, although mostly lower-middle class, which along with the presence of the Runosmäki estate means it's a good seat for the SDP specifically.

63: Turku West (

Länsi-Turku,

Åbo västra)

19,893 (-1,018)

I wasn't able to settle on a good name for this seat, as it covers part of the Maaria and Mikael parishes, both of which have their seats in other constituencies, and no one suburb really seems dominant - though there is a commercial area called

Länsikeskus (West Centre), so with that in mind I think just calling it Turku West is acceptable. This part of the city is mostly working-class and was built to house workers for the shipyard, which is now located in Perno at the western edge of the constituency. The shipbuilders used to be a solid Communist constituency, and the Left remains quite strong here, but as with #60, vote splitting (and the Finns presence) is strong enough to hand it to the Coalition.

64: Turku Harbour (

Turun satama,

Åbo hamn)

23,664 (+2,753)

Although this seat includes the western edge of the city centre, its main focus is the islands along the coast, which are thoroughly middle-class and vote for the Coalition by wide margins. The mainland part of the seat is more akin to #60 in its politics, with a formerly-strong Green presence that's given way to vote splitting and a narrow Coalition plurality. Still a blue seat, in other words.

65: Turku-Henrikki (

Åbo-Henriks)

19,461 (-1,450)

A largely middle-class seat made up of suburbs built after the war in what was formerly Kaarina municipality, annexed into the city in 1939. While not as safe as #64, all of the areas here tend to vote Coalition, so they'll likely win the seat handily.

66: Turku-Varissuo (

Åbo-Kråkkärret)

19,079 (-1,832)

Varissuo, literally "Crow's Moor", is Turku's most infamous housing estate, built in the 1970s and largely housing working-class people of all ethnic backgrounds. Unlike the older working-class neighbourhoods and the university area, Varissuo and its surroundings seem to have always voted SDP, and the seat remains their safest in the city.

67: Raisio (

Reso)

26,109 (+5,198)

Turku added up to a bit more than seven seats, so the solution I went with was to combine its (very rural) northern extremity with some of the suburban municipalities nearby, resulting in this apparently oversized seat. You'll eventually see why there was a surplus that needed to be distributed, though perhaps there could've been a more elegant solution than this. Either way, Raisio proper is similar to the areas of Turku across the border from it (seat #63), having started out as overspill housing for harbour and shipyard workers, and as such used to be solidly left-wing. Since 2011, though, the Finns have made strides here, which combined with the Centre collapse taking out their stronghold in the north of the seat has meant that this is a somewhat safe yellow seat in 2023.

68: Naantali (

Nådendal)

20,062 (-849)

Naantali, a medieval town that originally hosted a nunnery (the Swedish name "Nådendal" literally means "valley of grace"), but is now primarily known as a summer place, being host to the President's country residence at Kultaranta as well as the Moominworld theme park. A lot of the permanent population commutes to Turku, and their voting lean is similar to that of the islands in Turku proper - Naantali has always been a Coalition-voting town, and 2023 is no exception.

69(nice): Mynämäki (

Virmo)

20,732 (-179)

This is a mostly-rural seat made up of a number of small villages along the coast and the road between Turku and Pori. Traditionally would've been a Centre stronghold, now it's a Finns stronghold instead.

70: Uusikaupunki (

Nystad)

19,711 (-1,200)

Uusikaupunki ("new town") has been home to a car factory run by Valmet since the 1960s, and a number of other industries remain present in the town. It still seems to slot neatly into the "post-industrial regional town" mould, going from an SDP stronghold to one for the Finns over the 2010s.

71: Loimaa

19,617 (-1,294)

This seat covers the entire interior of Finland Proper, an area that was mostly considered part of Satakunta until the 20th century. Loimaa itself is home to the Finnish Agricultural Museum, which should tell you all you need to know about its former political leanings, but today it's a reasonably safe Finns seat.

72: Lieto (

Lundo)

21,806 (+895)

This is a mixed seat that stretches from Turku's suburbs up to the border with Häme. Although Lieto proper (the closest area to Turku) voted for the Coalition, the rest of the seat was quite weak for them, and I believe this would be enough to let the Finns come out on top, although it would likely be a close race.

73: Kaarina (

S:t Karins)

21,719 (+808)

The aforementioned municipality of Kaarina, which used to cover a good chunk of what's now Turku as well, is thoroughly suburban and middle-class, and as a result votes for the Coalition by a decent enough margin.

74: Paimio (

Pemar)

23,307 (+2,396)

Another "small towns along the coast" seat, which is mostly situated along the railway line between Turku and Helsinki - although every single station in the constituency is closed, Finland outside Helsinki being a bit behind on the regional rail revival. The area doesn't seem to suffer too badly though, as most of it voted for the Coalition.

75: Salo

20,906 (-5)

Salo is probably best known for the Nokia mobile phone factory, which was located here from 1979 until 2015, when production was offshored. There's still a substantial high-tech industry in the town, though, just not the manufacturing side. The closure still hit the town hard, as most of the workers weren't exactly in a position to get computer science degrees, and unemployment continues to be high leading to a strong Finns presence. The town proper, however, voted for the SDP by a decent margin in 2023.

76: Somero-Perniö

19,286 (-1,625)

This seat combines the municipality of Somero with Salo's rural fringe, and resembles #71 politically: a formerly safe area for the Centre, which now votes for the Finns by a good margin.

77: Åboland (

Turunmaa)

17,255 (-3,656)

Remember how I mentioned that there was always going to be a surplus? This is why. The two Swedish-speaking municipalities in the Åboland archipelago, Pargas and Kimitoön, are

almost big enough for a seat when combined, but there's not really any one area that would be suitable to combine them with. I decided it'd make more sense to leave them aside, with the same justification as for the Österbotten seats. It's a reasonably safe SFP seat, although not quite as safe as those.

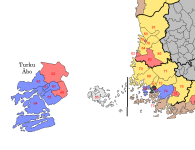

Satakunta (8 constituencies, quota 21,225)

78: Pori Central (

Keski-Pori, Björneborg centrala)

22,516 (+1,291)

Pori is a kind of poster child for post-industrial malaise in Finland: it was traditionally a manufacturing and textile town, and in the 1960s turned down the offer of a university campus because it was felt that the local industries provided sufficient economic opportunity without the need for one. Cue the 90s, and unemployment in the city hit 25%. Recovery has been slow and painful, and the city is smaller today than it was in 1975. Not surprisingly, the Finns have done very well here for most of their history, although the formerly-dominant SDP is still a strong factor in local politics. Enough so, most likely, to win the central seat, although the Coalition also has a presence here and I honestly couldn't say for sure who is stronger.

79: Pori West (

Länsi-Pori, Björneborg västra)

20,857 (-368)

Aside from the central seat, I've divided Pori roughly along the Kokemäki river, which seems to provide a neat enough split. The west bank of the river was the seat of many of the aforementioned heavy industries, and most of the residential areas here are working-class - then again, that's true of most of the city. Likely a safe-ish SDP seat in the past, today it's reasonably good for the Finns.

80: Pori East (

Itä-Pori, Björneborg östra)

22,183 (+958)

Again, Pori doesn't seem to have a huge geographic divide within it, but if anything it seems like the east of the city is slightly more middle-class. Doesn't matter too much though, as this seat is also a safe Finns one.

81: Northern Satakunta (

Pohjois-Satakunta)

19,899 (-1,326)

Yet another rural seat that used to vote Centre and now votes Finns. The biggest settlement in the seat is Kankaanpää, which by all accounts was an early Finns stronghold, and the entire thing voted for them by imposing margins in 2023.

82: Rauma

21,131 (-94)

Rauma is an old port town with a strong (though nearly extinct) local dialect, and it still has a strong industrial presence mainly centred around the harbour and the UPM-Kymmene paper mill. Unlike most other such places, the SDP still dominates here, although part of that may be that they had further to fall - it used to be their single biggest stronghold in Finland alongside Varkaus (also a paper mill town - coincidence?).

83: Eura

21,812 (+587)

This seat includes bits of Rauma as well as its namesake municipality, both of which are still SDP strongholds.

84: Ulvila (

Ulvsby)

21,157 (-68)

Ulvila was formerly one of Finland's six medieval market towns, but when the harbour silted up as a result of post-glacial rebound, Pori was founded further downriver to replace it. Ulvila has since become a suburb of Pori, and does sort of alright as a result, but not great given the city it's next to. Although Eurajoki (the coastal part of the seat, most notable as the home of Olkiluoto nuclear power station) voted SDP, the rest went for the Finns by enough of a margin to carry the seat.

85: Kokemäki (

Kumo)

20,246 (-979)

This seat actually has three roughly-equal population centres, Kokemäki itself, Harjavalta and Huittinen, all of which are former industrial towns along the Kokemäki river. None of them are doing that hot, and a former SDP-Centre swing seat is now a safe Finns one.

Landskapet Åland (

Ahvenanmaan maakunta) (1 constituency, electorate 21,557)

86: Åland (

Ahvenanmaa)

Åland is, of course, special. Luckily for us, its electorate is almost exactly right for one seat, which is likely contested by an entirely different set of parties from the mainland ones. If the situation is anything like OTL, however, there'll be a dominant bloc of centre-right parties which nominates a unity candidate who then sits with the SFP once elected. As such, although the seat is marked independent grey on the map, I'm counting it as an SFP seat for the purposes of the total.

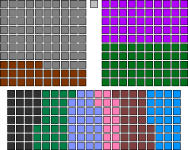

Regional subtotal

Finns 11

Coalition 8

SDP 6

SFP 1+1

National total (thus far)

Coalition 46

Finns 36

SDP 35

Centre 19

SFP 11+1

Left 2