- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

The years following the end of the First World War were not an easy time for Europe, as the major powers reeled from the devastation of war and the new states of Central and Eastern Europe struggled to establish themselves and find a place in the global political and economic order. For a country like Denmark, firmly established as a state and as a nation with its own identity and largely untouched by the war itself, the political side of the post-war crisis was hardly felt - the Folketing elected in September 1920 yielded a relatively stable government and lasted three and a half years - but the economic side reared its head before too long. Denmark's biggest source of economic activity was selling surplus agricultural products to Germany and the UK, and with Germany in an economic tailspin, the Danish economy soon felt the effects. In 1922, Landmandsbanken, the biggest bank in Denmark and an institution that specialised in providing loans to farmers, declared bankruptcy, after which it was revealed that it had been systematically padding its books for years. The Rigsdag was forced to step in and provide a reconstruction plan, and (this is how you can tell it was a hundred years ago) several of the bank's executives were tried and jailed for fraud. Emil Glückstadt, the managing director, was found guilty and sentenced to prison time, but died before the sentence could be carried out.

The Landmandsbanken case marked the beginning of two unstable years for the Neergaard ministry, which only held minorities in either house of the Rigsdag and relied on support from the Conservatives to pass its programme. This turned out to be a big issue in light of the crisis, since the two parties' main ideological disagreement was trade policy. Venstre, being a right-liberal farmers' party, continued to believe in free trade and free markets, while the Conservatives believed tariffs were more necessary than ever to protect the Danish economy from predatory foreign actors. On top of which the krone was suffering heavy inflation (not as heavy as that of the German mark, but still), which would need government action to get back in check. Eventually, after many government crises, Neergaard was able to get his revaluation plan through the Folketing in early 1924, and went to the country immediately thereafter in the hopes of being able to present a strong record in government.

This met with mixed success, to say the least. The country was still in a deep recession, and most voters did not see Venstre as a party that had fought their corner especially hard over the previous four years. On top of this, it was pretty widely recognised that a new Venstre ministry would have to depend on Conservative votes, and that that would mean continued confusion over trade and economic policy. The Conservatives themselves underscored this point by attacking the government for not taking strong enough action to protect Danish businesses, while the opposition happily seized on the disunity to underline their calls for a strong and resolute government that would make all Danes better off. The Social Democrats proposed a plan to fight inflation and the rising deficit by instituting wealth and luxury taxes, which caused some rumblings among their opponents, but overall the party did not seem as radical as it had in the past, and more and more voters saw them as the less bad option.

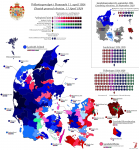

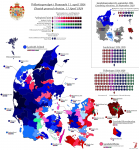

When the country went to the polls, this was clearly and dramatically reflected. For the first time ever, the Social Democrats received not only the largest voteshare but the largest delegation in the Folketing, taking seven seats from Venstre and giving the lower house a slight left-wing majority for the first time since 1918. Nor would they return to passively supporting a Radical ministry - Zahle was never going to come back within eyesight of the King, and the Social Democrats held a clearly dominant position in a way they hadn't the previous time, so they were able to insist upon their own ministry led by party leader Thorvald Stauning, who had chaired the Copenhagen City Council during the Easter Crisis and was relatively respected by the King despite his working-class origins (he'd originally worked as a cigar sorter before becoming a trade union organiser and then entering party politics). Stauning's ministry made history on its first day by including Nina Bang, the first woman to serve in a parliamentary government anywhere in the world (the first overall being Alexandra Kollontai), as education minister. Of course, the parliamentary situation was essentially the same as before the election, only in reverse, and so it remained to be seen how much of its economic programme the new ministry would be able to get past the Radicals.

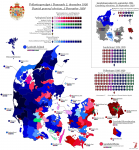

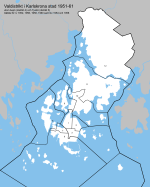

Oh, and in September, the Landsting held its first regular election since the 1920 dissolutions. Half of the constituency seats were renewed, but the members elected by the outgoing Landsting in 1920 all remained in place. It didn't yield too many surprises, with slight gains for the Social Democrats but a continued strong right-wing majority.

The Landmandsbanken case marked the beginning of two unstable years for the Neergaard ministry, which only held minorities in either house of the Rigsdag and relied on support from the Conservatives to pass its programme. This turned out to be a big issue in light of the crisis, since the two parties' main ideological disagreement was trade policy. Venstre, being a right-liberal farmers' party, continued to believe in free trade and free markets, while the Conservatives believed tariffs were more necessary than ever to protect the Danish economy from predatory foreign actors. On top of which the krone was suffering heavy inflation (not as heavy as that of the German mark, but still), which would need government action to get back in check. Eventually, after many government crises, Neergaard was able to get his revaluation plan through the Folketing in early 1924, and went to the country immediately thereafter in the hopes of being able to present a strong record in government.

This met with mixed success, to say the least. The country was still in a deep recession, and most voters did not see Venstre as a party that had fought their corner especially hard over the previous four years. On top of this, it was pretty widely recognised that a new Venstre ministry would have to depend on Conservative votes, and that that would mean continued confusion over trade and economic policy. The Conservatives themselves underscored this point by attacking the government for not taking strong enough action to protect Danish businesses, while the opposition happily seized on the disunity to underline their calls for a strong and resolute government that would make all Danes better off. The Social Democrats proposed a plan to fight inflation and the rising deficit by instituting wealth and luxury taxes, which caused some rumblings among their opponents, but overall the party did not seem as radical as it had in the past, and more and more voters saw them as the less bad option.

When the country went to the polls, this was clearly and dramatically reflected. For the first time ever, the Social Democrats received not only the largest voteshare but the largest delegation in the Folketing, taking seven seats from Venstre and giving the lower house a slight left-wing majority for the first time since 1918. Nor would they return to passively supporting a Radical ministry - Zahle was never going to come back within eyesight of the King, and the Social Democrats held a clearly dominant position in a way they hadn't the previous time, so they were able to insist upon their own ministry led by party leader Thorvald Stauning, who had chaired the Copenhagen City Council during the Easter Crisis and was relatively respected by the King despite his working-class origins (he'd originally worked as a cigar sorter before becoming a trade union organiser and then entering party politics). Stauning's ministry made history on its first day by including Nina Bang, the first woman to serve in a parliamentary government anywhere in the world (the first overall being Alexandra Kollontai), as education minister. Of course, the parliamentary situation was essentially the same as before the election, only in reverse, and so it remained to be seen how much of its economic programme the new ministry would be able to get past the Radicals.

Oh, and in September, the Landsting held its first regular election since the 1920 dissolutions. Half of the constituency seats were renewed, but the members elected by the outgoing Landsting in 1920 all remained in place. It didn't yield too many surprises, with slight gains for the Social Democrats but a continued strong right-wing majority.