A

lot happened between 1919 and 1922 in Poland, indeed, probably too much to write here. Unquestionably the biggest thing was the Polish-Soviet War, in which Polish forces advancing east to reclaim former Polish lands and realise Józef Piłsudski's ambition of creating a Poland strong enough to defend itself from the neighbouring great powers rather inevitably came into conflict with Red Army forces advancing west to link up with the German Spartacists and kickstart the world revolution. The Soviets did pretty well for a long time, but were finally stopped at the gates of Warsaw in August 1920, in what became known in Polish historiography as the "Miracle on the Vistula". Soon enough, the Poles were marching east again, and in March 1921, the Polish and Soviet governments signed a peace treaty in Riga, which drew a very favourable eastern border for Poland. They didn't get the entire former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as Piłsudski had wanted, sure, but all of Galicia and Volhynia and a good chunk of Belarus ended up in Polish hands. At about the same time, the border with Germany was finalised following plebiscites in Masuria and Upper Silesia. Those borders ended up less favourably for Poland, because the plebiscites had been held right when it seemed like the Polish state was on the verge of collapse, and so plenty of Polish-speaking locals voted to stick with the devil they knew.

Far from all of these territories were ethnically Polish. Minorities existed almost everywhere, sure, but most of the eastern lands (the

Kresy, which just means "border regions" in Polish) were majority East Slavic, and the former German partition had sizeable German minorities throughout. And, of course, there were Jewish communities all over the country. Most of the Jews in Germany had made a strong effort to assimilate and speak Standard German after the ghettos were dissolved, but in Galicia and the Russian partition, where they were surrounded by Slavic peoples rather than Germans, this was understandably quite a lot harder - not to mention the repression they faced from Russian state authorities in particular. So there was a very strong Jewish identity in Poland at this time, and the Yiddish language was one of the largest minority languages in the country with over two million native speakers. Although opinion was divided among these groups on whether they ought to be part of Poland, most of them recognised the threat of Polish ethnonationalism winning control of the new state, and at the initiative of Yitzhak Grünbaum, a veteran Jewish community leader and journalist, a number of different minority groups united for the November 1922 parliamentary elections as the

Bloc of National Minorities (

Blok Mniejszości Narodowych,

BMN). The BMN's leadership was made up of an equal number of Jews, Germans, Ukrainians and Belarusians, although Grünbaum acted as the unofficial leader of the movement, his skills as a journalist and community organiser carrying over very well into parliamentary work. The BMN didn't gather quite every minority group, however, with several Jewish and Ukrainian groups staying out of it - most of the latter boycotted the elections altogether, dismayed by the way Poland had subsumed the West Ukrainian People's Republic in 1919.

It may be worth stopping here to dwell on the nature of Polish nationalism, which had been divided into two broad camps even before the war. As mentioned, Piłsudski was an advocate of territorial expansion, believing that Poland would never be able to defend its independence if it didn't cement itself as a significant player in European politics in its own right. Supporters of this style of Polish nationalism, known as the "Jagiellon Concept" after the royal house that had built up the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, believed in a place for ethnic diversity, carrying on the PLC's tradition of being somewhat welcoming to groups like the Jews and the Greek Orthodox Eastern Slavs, but also generally believed that the Poles had a historic role as the leading ethnicity of the state and that the other ethnic groups in the area would welcome them as liberators. On the other hand, there were the supporters of the "Piast Concept", named for the dynasty of dukes and kings who founded the Polish state in the 10th and 11th centuries. Led by the

National Democracy (

Narodowa Demokracja,

ND or

Endecja) movement, they were generally a lot less keen on expanding Poland's borders, and a lot more keen on making sure any Polish state was politically stable and homogenously Polish. In their view, the expansive and permissive nature of the PLC was precisely the thing that had made it vulnerable, and military adventures by the new Polish state were only bound to make enemies of the peoples around them. The important things would be to secure a close relationship with the West, especially with fellow Catholic powers like France, and to make sure that (Catholic) Poles would be the masters of their own destiny within Poland. It shouldn't surprise you that they pretty much all saw the Jews as the single biggest threat to this, and that's worth bearing in mind for the 1928 election especially.

In 1922, there wasn't really an organised political party advocating for Polish nationalism based on the Jagiellon Concept, which might come as a surprise given that its proponents had effectively governed Poland since 1919. However, that power was concentrated in the person of Józef Piłsudski, who relied on emergency laws to impose his will on the administration. The Legislative Sejm, on the other hand, was dominated by Piast Concept supporters, who drew up a constitution modelled on the French one with a very strong parliament and a ceremonial presidency. This annoyed Piłsudski so much that he refused to stand for the presidency and declared he would retire from politics as soon as a successor could be elected. Obviously, this emboldened his rivals, chief among them the

Endecja's political wing the

People's National Union (

Związek Ludowo-Narodowy,

ZLN), who formed an electoral alliance with the

Polish Christian Democratic Party (

Polskie Stronnictwo Chrześcijańskiej Demokracji,

PSChD or

Chadecja) led by Silesian activist and former Reichstag deputy Wojciech Korfanty, as well as a number of other right-wing Christian groups who formed the

Christian-National Club (

Klub Chrześcijańsko-Narodowy,

KChN). This alliance was dubbed the

Christian Association of National Unity (

Chrześcijański Związek Jedności Narodowej - you'll sometimes see this rendered as "Christian

Union of National Unity", but I'm choosing to avoid the tautology since it's not there in Polish). Local wits decided to abbreviate this name to

Chjena, which is pronounced like "hyena", and despite their own protests, this abbreviation very quickly became ubiquitous.

The

Chjena's mockers could laugh all they wanted, because the situation was very clearly favourable for the alliance. In western Poland, especially the ZLN's strongholds in Greater Poland and the

Chadecja's one in Silesia, they were completely dominant, and although they were a lot weaker elsewhere in the country, they won a commanding lead in the popular vote with almost 30% of the Sejm vote and almost 40% of that for the Senate (which had a smaller electorate, I believe you had to be 30 to vote for it and 40 to stand for election). Of course, that's not a majority, and the rest of the scene was divided between the BMN, the two different PSL factions left standing, and the PPS, in addition to a gaggle of smaller parties. None of them got along very well, but they all hated the

Endecja enough to block them from influence. When the new National Assembly met in joint session to choose a president, the

Chjena's candidate, the Ambassador to Paris Count Maurycy Zamoyski, lost by a fairly big margin to Piłsudski's preferred candidate, the renowned engineer, PSL-"Wyzwolenie" member and former Minister of Public Works Gabriel Narutowicz. However, after just five days in office, Narutowicz was assassinated by a rogue art critic and

Endecja supporter named Eligiusz Niewiadomski (these names, my God), and the election had to be rerun. Once again, the Chjena put up a candidate, this time the historian Kazimierz Morawski, who again lost, this time to the PSL-"Piast" politician Stanisław Wojciechowski, a friend of Piłsudski's who had been active in the PPS alongside him back in the 1890s. Although thought close to Piłsudski, Wojciechowski would in time become one of his key enemies, as discontent with the unstable parliamentary regime of which Wojciechowski was the figurehead grew out in the country.

Speaking of which, although the new Sejm was able to elect a president twice over, forming a government proved rather harder. The nonpartisan, but conservative, ministry led by Julian Nowak continued in office through most of December, being replaced by a caretaker ministry headed by General Władysław Sikorski (who played a key role in the Miracle on the Vistula and would play an even more key role in the Second World War). This lasted well into 1923 before a parliamentary government could finally take office, headed by Wincenty Witos of the PSL-"Piast" and comprised of them and the

Chjena parties (to give some idea of how universal that name had become, the coalition was known as the

Chjeno-Piast). This in turn lasted about six months, and then the carousel started back up again.

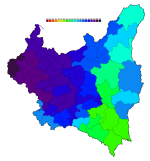

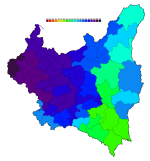

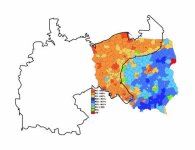

As a corollary, I made a turnout map, which I think is a pretty good illustration of what would become known as the "Poland A"/"Poland B" divide. Areas west of the Vistula, including Western Galicia to some extent, were generally highly industrialised, highly literate and highly politically conscious, which is reflected here in turnout levels of around 80%. The east, on the other hand, tended to be a lot less economically developed and also a lot less ethnically Polish - the figures for Eastern Galicia specifically are affected by the Ukrainian boycott, and those constituencies will look

very different in the next election, but then again, so will the entire country. Because you see, not all was well in the state of Poland, and the military especially were deeply dismayed to watch the country they had fought to liberate descend into political backstabbing and corruption within months of its creation. Rumblings were heard through the barracks and the boardrooms, calling for a "cleansing" (

sanacja) of the Polish body politic, and they would soon find backing from the highest possible quarters.