Before dawn, 2nd April 1982. Argentina launched an invasion of the British-held Falkland Islands, known in Spanish as Las Malvinas. Frogmen landed first from a submarine, followed later by the main assault force. It was an historic day. One group attacked the capital from the landward side, another from sea. Soldiers occupied the radio stations and captured people inside. By 7 AM, after fierce fighting, Government House was completely surrounded; British marines ultimately gave up their arms. The islands were a national cause in Argentina. Pupils in primary schools learned about their lost heritage and how the British stole the islands from them in 1833. Even an unpopular dictatorship would be acclaimed if it could realise the dream of recovering Las Malvinas. When news of the invasion reached Buenos Aires, the crowds went wild. The military regime's record of violent repression, economic decline: all had been forgotten overnight.

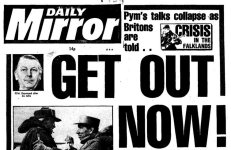

In London, there was outrage that the Government could allow British sovereign territory to be invaded. Rowdy scenes erupted in Parliament, swiftly followed by resignations. "It is a national humiliation," admitted Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington, who dismissed the notion that a "minister responsible should just go on as if nothing had happened." Margaret Thatcher gave an urgent statement to the Commons. "Mr Speaker, I'm sure that the whole House will join me in condemning totally, this unprovoked aggression by the Government of Argentina." MPs cheered. "It has not a shred of justification and not a scrap of legality." The Prime Minister sounded resolute, with indications of support from her backbenches. "When [the Governor] left the Falklands, he said the people were in tears. They do not want to be Argentine. He said the islanders are still tremendously loyal." As she praised the man's conduct, Mrs Thatcher could not help but notice heckles against her own policy of defence cuts from members of Labour, the SDP and Liberals. "It is the Government's objective to see that the islands are freed from occupation and are returned to British administration at the earliest possible moment." The United Kingdom's prestige was severely damaged. Its leadership now turned to the Armed Forces.

Lining jetties and walls, thousands of people waved farewell to the British Task Force at the start of its 8,000-mile journey to the South Atlantic. By the end of the week, half of the Royal Navy were mobilised and pushing south. 26,000 service people boarded the ships. Privately, Thatcher had many doubts, worries and fears about the mission. US Secretary of State Alexander Haig flew to London with the aim of brokering peace discussions, then to Buenos Aires. The Reagan Administration were keen not to fall out with either party in the conflict. Negotiations collapsed, with Haig returning empty-handed to Washington on 19th April. After three weeks at sea, the Task Force approached the Falklands. The Argentine navy closed in. UK officials intercepted a signal that The General Belgrano and aircraft carrier were part of an encirclement force on the attack. Thatcher held a war cabinet meeting at Chequers, where the developing situation became known to her. A submarine was ordered to torpedo The Belgrano, Argentina's only cruiser. It was attacked just outside the 200-mile exclusion zone around the Falklands, on the controversial basis that it posed a threat to the Task Force. Approximately 700 people on the warship sank.

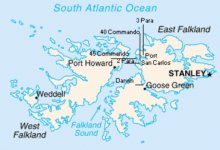

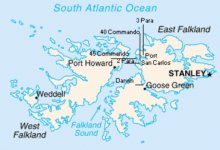

Meanwhile, the frigates Brilliant and Yarmouth were sent to hunt the San Luis, an Argentine submarine. The German-built vessel escaped again and again, proving a distraction to Royal Navy operations. On 4th May, an Exocet missile hit the destroyer HMS Sheffield, causing it to sink days later. 20 people died and many more were injured. The UN Secretary General reported that his attempt to mediate in the Falklands crisis had failed. Mrs Thatcher, watching these events unfold, believed that were a military response to the Argentine invasion unsuccessful, the sense of humiliation in Britain would probably grow out of control. In unpredictable Atlantic weather, her Task Force undertook an amphibious landing on hostile territory without air superiority. British troops went ashore in a number of raiding parties. 5,000 were landed after midnight in San Carlos, a port settlement in northwestern East Falkland - it was an astonishing feat. That is when the Argentine air attacks started.

In London, there was outrage that the Government could allow British sovereign territory to be invaded. Rowdy scenes erupted in Parliament, swiftly followed by resignations. "It is a national humiliation," admitted Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington, who dismissed the notion that a "minister responsible should just go on as if nothing had happened." Margaret Thatcher gave an urgent statement to the Commons. "Mr Speaker, I'm sure that the whole House will join me in condemning totally, this unprovoked aggression by the Government of Argentina." MPs cheered. "It has not a shred of justification and not a scrap of legality." The Prime Minister sounded resolute, with indications of support from her backbenches. "When [the Governor] left the Falklands, he said the people were in tears. They do not want to be Argentine. He said the islanders are still tremendously loyal." As she praised the man's conduct, Mrs Thatcher could not help but notice heckles against her own policy of defence cuts from members of Labour, the SDP and Liberals. "It is the Government's objective to see that the islands are freed from occupation and are returned to British administration at the earliest possible moment." The United Kingdom's prestige was severely damaged. Its leadership now turned to the Armed Forces.

Lining jetties and walls, thousands of people waved farewell to the British Task Force at the start of its 8,000-mile journey to the South Atlantic. By the end of the week, half of the Royal Navy were mobilised and pushing south. 26,000 service people boarded the ships. Privately, Thatcher had many doubts, worries and fears about the mission. US Secretary of State Alexander Haig flew to London with the aim of brokering peace discussions, then to Buenos Aires. The Reagan Administration were keen not to fall out with either party in the conflict. Negotiations collapsed, with Haig returning empty-handed to Washington on 19th April. After three weeks at sea, the Task Force approached the Falklands. The Argentine navy closed in. UK officials intercepted a signal that The General Belgrano and aircraft carrier were part of an encirclement force on the attack. Thatcher held a war cabinet meeting at Chequers, where the developing situation became known to her. A submarine was ordered to torpedo The Belgrano, Argentina's only cruiser. It was attacked just outside the 200-mile exclusion zone around the Falklands, on the controversial basis that it posed a threat to the Task Force. Approximately 700 people on the warship sank.

Meanwhile, the frigates Brilliant and Yarmouth were sent to hunt the San Luis, an Argentine submarine. The German-built vessel escaped again and again, proving a distraction to Royal Navy operations. On 4th May, an Exocet missile hit the destroyer HMS Sheffield, causing it to sink days later. 20 people died and many more were injured. The UN Secretary General reported that his attempt to mediate in the Falklands crisis had failed. Mrs Thatcher, watching these events unfold, believed that were a military response to the Argentine invasion unsuccessful, the sense of humiliation in Britain would probably grow out of control. In unpredictable Atlantic weather, her Task Force undertook an amphibious landing on hostile territory without air superiority. British troops went ashore in a number of raiding parties. 5,000 were landed after midnight in San Carlos, a port settlement in northwestern East Falkland - it was an astonishing feat. That is when the Argentine air attacks started.

Last edited: