-

Hi Guest!

The costs of running this forum are covered by Sea Lion Press. If you'd like to help support the company and the forum, visit patreon.com/sealionpress

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Breaking the Mould Redux: A Wikibox Timeline

- Thread starter Lucon50

- Start date

1983 proved, in many ways, to be a change election both in terms of political alignment and operation. While the scribbling out and re-drawing of constituency boundaries has been discussed, it also witnessed a brand-new style of campaigning and party loyalties based on demographic shifts. The Liberal/SDP Alliance as it was - headed by two leaders with one joint manifesto leaving out several policy differences between the pair - innovated collegiate and professional techniques formerly alien to Britain. Television and listening exercises featured more centrally. The Alliance was able to drum up most of its potential support in the centre ground and establish solid ideological roots. Its voters ranged from Guardian readers to right-wingers and people with rather discordant positions overall: for example, SDP voters were close to Labour on state spending and nearer to the Conservatives on trade union reform. Its social base comprised many public sector workers in the middle income bracket. However, the Alliance drew unemployed and impoverished sections of society to their cause by attacking the Tory record harshly while emphasising Liberal/SDP plans for investment and compassion. 'A Fresh Start for Britain' document, published as Alliance ministers took office, formalised the coalition manifesto.

Labour and Tory hopes had been cruelly dashed by the general election outcome. Combined, the party duopoly maintained since 1924 took only 55.4% of votes cast - a sharp fall on the gradual post-war decline which handed them around 80% just four years earlier. Newspapers described a "wipe-out" for Mrs Thatcher's army, reduced to third nationally and worse in some parts. Boasting a mere 108 seats, it was factually the worst ever result recorded by the Conservatives in history and represented a bleak situation indeed. For Labour, anti-socialists pointed to the terrible vote number while leftists attributed their runner-up in terms of seats to an energetic fight by Tony Benn and the grassroots. At a rally in Central Hall, Westminster, David Steel and the Gang of Four drew hundreds of supporters to celebrate the Alliance's victory in reshaping the political map in its favour. Upon entering power, any conflict on major policy would be resolved by these leading lights alongside Liberal ministers Alan Beith, David Penhaligon and Russell Johnston. Incoming SDP foreign secretary David Owen heaped praise on Shirley Williams, calling the new Parliament Britain's "most progressive ever", beating 1906 on that score.

MPs and Lords arrived in the halls of power on 18 January for the swearing-in of members and election of the Commons speaker. Reading out her new Government's programme a week after, the Queen detailed its main commitment as lowering the number of jobless to a million over the following two years, without a spike in the rate of inflation. This task appeared challenging but necessary. £3 billion of extra borrowing, together with a cancellation of the nuclear weapons upgrade from Polaris to Trident, would fund the emergency spending. It would be supported by a "fair and effective" pay and prices mechanism. Steel's core Liberal ideas on taxation and public works would be saved until the expected February budget, covering fiscal and monetary ambitions. Other plans included: the radical restructuring of the welfare state, with a longer-term goal of integrating tax and benefit systems; anti-poverty measures; greater democracy in the trade unions; profit-sharing and employee share-ownership in firms; a massive expansion of education and training (particularly for young workers); and a halt to both nationalisation and privatisation. The sale of British Telecom would not go ahead.

Next, the Queen spelled out out her Government's bold constitutional reform agenda. The terms of the European Convention on Human Rights would be written into British law as a bill of rights; legislation introduced, providing for wide access to official information. The "shifting of power to regions and local authorities" began with imminent devolution to a Scottish Parliament able to levy taxes without running a deficit. Welsh and English regional assemblies should follow, if given consent via referenda. A system of proportional representation based on multi-member constituencies and the single transferable vote would be introduced on the statute book without delay. Steel and Williams described electoral reform as "the linchpin of our entire programme" and a precondition of "healing Britain's divisions" that would "transform the character of our politics". Concluding her speech, the Queen articulated the Government's underlying themes of intention: national unity in the wake of strife and partnership between all sections of the community, banishing extremism. The Alliance would be economically "tough" but socially "tender". Reform of industry was married to a liberal position on matters of foreign policy, defence and individual rights. Notably typifying SDP majority views, the Government would harness a mixed economy and welfare capitalism to produce the wealth it planned to redistribute and lower inequality.

Labour and Tory hopes had been cruelly dashed by the general election outcome. Combined, the party duopoly maintained since 1924 took only 55.4% of votes cast - a sharp fall on the gradual post-war decline which handed them around 80% just four years earlier. Newspapers described a "wipe-out" for Mrs Thatcher's army, reduced to third nationally and worse in some parts. Boasting a mere 108 seats, it was factually the worst ever result recorded by the Conservatives in history and represented a bleak situation indeed. For Labour, anti-socialists pointed to the terrible vote number while leftists attributed their runner-up in terms of seats to an energetic fight by Tony Benn and the grassroots. At a rally in Central Hall, Westminster, David Steel and the Gang of Four drew hundreds of supporters to celebrate the Alliance's victory in reshaping the political map in its favour. Upon entering power, any conflict on major policy would be resolved by these leading lights alongside Liberal ministers Alan Beith, David Penhaligon and Russell Johnston. Incoming SDP foreign secretary David Owen heaped praise on Shirley Williams, calling the new Parliament Britain's "most progressive ever", beating 1906 on that score.

MPs and Lords arrived in the halls of power on 18 January for the swearing-in of members and election of the Commons speaker. Reading out her new Government's programme a week after, the Queen detailed its main commitment as lowering the number of jobless to a million over the following two years, without a spike in the rate of inflation. This task appeared challenging but necessary. £3 billion of extra borrowing, together with a cancellation of the nuclear weapons upgrade from Polaris to Trident, would fund the emergency spending. It would be supported by a "fair and effective" pay and prices mechanism. Steel's core Liberal ideas on taxation and public works would be saved until the expected February budget, covering fiscal and monetary ambitions. Other plans included: the radical restructuring of the welfare state, with a longer-term goal of integrating tax and benefit systems; anti-poverty measures; greater democracy in the trade unions; profit-sharing and employee share-ownership in firms; a massive expansion of education and training (particularly for young workers); and a halt to both nationalisation and privatisation. The sale of British Telecom would not go ahead.

Next, the Queen spelled out out her Government's bold constitutional reform agenda. The terms of the European Convention on Human Rights would be written into British law as a bill of rights; legislation introduced, providing for wide access to official information. The "shifting of power to regions and local authorities" began with imminent devolution to a Scottish Parliament able to levy taxes without running a deficit. Welsh and English regional assemblies should follow, if given consent via referenda. A system of proportional representation based on multi-member constituencies and the single transferable vote would be introduced on the statute book without delay. Steel and Williams described electoral reform as "the linchpin of our entire programme" and a precondition of "healing Britain's divisions" that would "transform the character of our politics". Concluding her speech, the Queen articulated the Government's underlying themes of intention: national unity in the wake of strife and partnership between all sections of the community, banishing extremism. The Alliance would be economically "tough" but socially "tender". Reform of industry was married to a liberal position on matters of foreign policy, defence and individual rights. Notably typifying SDP majority views, the Government would harness a mixed economy and welfare capitalism to produce the wealth it planned to redistribute and lower inequality.

Last edited:

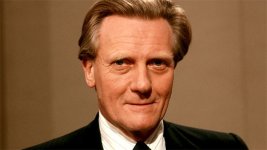

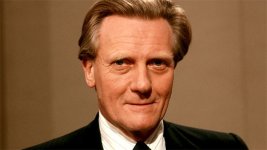

The electoral bloodbath left Conservatives shell-shocked, mad, bitter and in a state of denial. Liberal/SDP success had come primarily at the expense of Tory MPs, to the point at which Margaret Thatcher had even said Labour "will never die" during the campaign to shore up votes against the Alliance, rattled by the emerging picture. When she resigned the party leadership with immediate effect in January 1983, the Iron Lady expressed a desire for her successor to "promote free markets, financial discipline, firm control over public expenditure, tax cuts, de-nationalisation and moral values - putting country first". Long-serving deputy Willie Whitelaw became acting leader, ruling that a contest would be held with MPs selecting from candidates. Two-hundred booted from Parliament outnumbered the 108 survivors, ranging in each case from Keynesian 'wets' who blamed Mrs Thatcher's doctrinaire policy to non-ideological moderates/traditionalists and hard-liners on the reactionary, sometimes populist Tory right. In the weeks after "that bloody woman" stepped down, lobby briefings and open conflict consumed the party. First to declare his intention to succeed her was Michael Heseltine. Having served as environment secretary (heading the savvy Right to Buy initiative) and in charge of defence, he sought to represent the corporatist, pro-European left wing. Heseltine also called for more pluralism, engaging various strands of opinion.

Against him stood tough grassroots favourite Norman Tebbit, whom Michael Foot had once referred to as a "semi-housetrained polecat". Known for his venal hatred of socialism, cockney accent and sharp tongue, he outlined a policy of continuity with Thatcherism designed to retain working-class voters. Heseltine immediately drew the backing of Francis Pym, a scion of the one-nation, centrist faction. Allies outside Parliament also gave him their support, including Norman St John-Stevas, Peter Walker, Douglas Hurd, Peter Tapsell (despite his euroscepticism) and George Young. The prospect of a liberal restoration, consigning the troubled New Right experiment to history, was an attractive one. Mr Heseltine might have wished to include different sides in his nascent project, yet it was becoming evident that his supporters' deep-seated hatred of monetarism could provoke a vicious reaction. Mr Tebbit launched into a tirade on Friday 21 January, writing in The Daily Mail that Heseltine personified an "insufferable, smug, sanctimonious, naive, guilt-ridden, wet, pink orthodoxy". It was both a shocking and characteristic line of attack. Tebbit argued instead for the Conservatives to be a "national party of Great Britain", the voice of "all those who support the British tradition of democracy, of personal freedom, of personal responsibility for one's own affairs" without state intervention.

Mr Heseltine shot back. "They say a man should be judged by his enemies. I am very proud of mine." He asserted that "the market has no morality", putting down Tebbit on the grounds of substance and deriding the former PM, quipping that "you can't wield a handbag from an empty chair". Furiously, Heseltine said he "always knew that Norman belonged in the economic nursery". Another round of hostilities flared up soon after. "Michael would not recognise a principle if it were staring him in the face, unless it was about his own ego," said Tebbit, who complained that Heseltine "did his very best to undermine Mrs Thatcher". He underlined falling inflation, removal of "wasteful" spending and economic growth as indicators that neoliberal ideas worked at home, so long as British clout on the world stage could be made a twin priority. Figures from the Conservative Monday Club - a traditional right-wing pressure group - and young 'dries' quickly lined up behind Tebbit. Keith Joseph influenced the campaign, proposing the 'social market' model inspired by Christian democracy and a firm hand against both Alliance and Labour. With divisions in the spotlight, Tory poll ratings slid further. Heseltine suggested a return to consensus politics, which had been given a new electoral mandate; Tebbit, resolute development of the winning 1979 programme and only a stylistic change from the party's recent horror.

Eager to revive Conservative fortunes, interim leader Mr Whitelaw threw his hat into the ring, pitching himself as a unity candidate. Patrician, moderate and loyal, the contrast with Heseltine's flamboyance and Tebbit's fanaticism exposed the warring sides as dangerously schismatic. Whitelaw provided a bridge for the centre to traverse, bringing faces inside Parliament (such as Norman Fowler) and outside (e.g. independent Anthony Meyer) together with 'sensible' monetarists (like Leon Brittan, Nigel Lawson and a brow-beaten Geoffrey Howe). They all shared a distaste for the brewing Tory civil strife, preferring a middle ground. Data showed that while Heseltine's position was more attuned to Liberal and SDP voters, he represented a shrunken left in the Westminster caucus. Tebbit would do strongly in a hypothetical grassroots poll, backed in the right-wing media and carrying the Thatcherite flame. Mr Whitelaw, whose campaign managers sensed that the bulk of Conservative MPs sat somewhere between his rivals ideologically, appeared optimistic that party divisions would be settled by compromise. Seeking to fulfil this, he used every hour as acting leader to criticise the Government's measures and divert attention towards Labour. "Whatever mistakes there may have been, that's all in the past now. Much good work was done. I will continue to persuade the British public that we have to spend money on our services, on maintenance and improvements."

Against him stood tough grassroots favourite Norman Tebbit, whom Michael Foot had once referred to as a "semi-housetrained polecat". Known for his venal hatred of socialism, cockney accent and sharp tongue, he outlined a policy of continuity with Thatcherism designed to retain working-class voters. Heseltine immediately drew the backing of Francis Pym, a scion of the one-nation, centrist faction. Allies outside Parliament also gave him their support, including Norman St John-Stevas, Peter Walker, Douglas Hurd, Peter Tapsell (despite his euroscepticism) and George Young. The prospect of a liberal restoration, consigning the troubled New Right experiment to history, was an attractive one. Mr Heseltine might have wished to include different sides in his nascent project, yet it was becoming evident that his supporters' deep-seated hatred of monetarism could provoke a vicious reaction. Mr Tebbit launched into a tirade on Friday 21 January, writing in The Daily Mail that Heseltine personified an "insufferable, smug, sanctimonious, naive, guilt-ridden, wet, pink orthodoxy". It was both a shocking and characteristic line of attack. Tebbit argued instead for the Conservatives to be a "national party of Great Britain", the voice of "all those who support the British tradition of democracy, of personal freedom, of personal responsibility for one's own affairs" without state intervention.

Mr Heseltine shot back. "They say a man should be judged by his enemies. I am very proud of mine." He asserted that "the market has no morality", putting down Tebbit on the grounds of substance and deriding the former PM, quipping that "you can't wield a handbag from an empty chair". Furiously, Heseltine said he "always knew that Norman belonged in the economic nursery". Another round of hostilities flared up soon after. "Michael would not recognise a principle if it were staring him in the face, unless it was about his own ego," said Tebbit, who complained that Heseltine "did his very best to undermine Mrs Thatcher". He underlined falling inflation, removal of "wasteful" spending and economic growth as indicators that neoliberal ideas worked at home, so long as British clout on the world stage could be made a twin priority. Figures from the Conservative Monday Club - a traditional right-wing pressure group - and young 'dries' quickly lined up behind Tebbit. Keith Joseph influenced the campaign, proposing the 'social market' model inspired by Christian democracy and a firm hand against both Alliance and Labour. With divisions in the spotlight, Tory poll ratings slid further. Heseltine suggested a return to consensus politics, which had been given a new electoral mandate; Tebbit, resolute development of the winning 1979 programme and only a stylistic change from the party's recent horror.

Eager to revive Conservative fortunes, interim leader Mr Whitelaw threw his hat into the ring, pitching himself as a unity candidate. Patrician, moderate and loyal, the contrast with Heseltine's flamboyance and Tebbit's fanaticism exposed the warring sides as dangerously schismatic. Whitelaw provided a bridge for the centre to traverse, bringing faces inside Parliament (such as Norman Fowler) and outside (e.g. independent Anthony Meyer) together with 'sensible' monetarists (like Leon Brittan, Nigel Lawson and a brow-beaten Geoffrey Howe). They all shared a distaste for the brewing Tory civil strife, preferring a middle ground. Data showed that while Heseltine's position was more attuned to Liberal and SDP voters, he represented a shrunken left in the Westminster caucus. Tebbit would do strongly in a hypothetical grassroots poll, backed in the right-wing media and carrying the Thatcherite flame. Mr Whitelaw, whose campaign managers sensed that the bulk of Conservative MPs sat somewhere between his rivals ideologically, appeared optimistic that party divisions would be settled by compromise. Seeking to fulfil this, he used every hour as acting leader to criticise the Government's measures and divert attention towards Labour. "Whatever mistakes there may have been, that's all in the past now. Much good work was done. I will continue to persuade the British public that we have to spend money on our services, on maintenance and improvements."

Last edited:

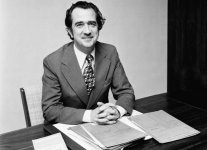

Bill Rodgers stood before the House of Commons to deliver the first Alliance budget on Tuesday 11 February. After working closely with Liberal and SDP partners in Whitehall, he'd brandished the chancellor's red box outside Downing Street and set off for Parliament. MPs from the Labour benches jeered, while the Tories were in disarray. Colleagues made supportive noises as Rodgers gave his reading of the economic state Britain found herself in. The other parties between them had "created an industrial wasteland", offering interference and confrontation from the left or bankruptcy and neglect from the right. Unemployment was at a record high of 20%. Mr Rodgers said that via his budget the Government would rescue the country, giving a "well-directed stimulus to the economy" and "firm and fair incomes policy". The human cost of joblessness and inefficiency would become a thing of the past. With vision and "enlightened self-interest" of the kind which produced the Marshall Plan, Britain could provide a leading international example. New social welfare reforms depended on funding by the taxation of wealth. "This budget comes from a government of national unity, comprising all the talents. It is the people's budget - for redistribution and the spreading of opportunity and power. Our democratic mission extends to all sections of the community, from elections to business. This Alliance budget delivers a new deal for every family in Great Britain."

The emergency budget promised: an inflation tax on 'excessive' wage rises; the usage of North Sea oil revenues to fund public services; a reflationary strategy with £3 billion of raised expenditure to boost demand and generate jobs; workforce education and training; incentives for co-operatives and social enterprises; a 2% tax on the value of land; subsidies for the private sector to take on new recruits; extra healthcare funding; and capital investment, upgrading assets such as roads, bridges and homes. The Government wanted to "put spades in the ground" immediately, looking ahead to the benefits of growth across the next few years. Whilst the structural changes planned would take some time to bear fruit, 1983 might be remembered as a "turning point" when the UK decided to reject "dogma and bitterness", instead venturing on "a new road of partnership and progress". Rodgers laid out his goals as chancellor. "Our concern is for the long term, not just for tomorrow. We do not want to solve our immediate problems by piling up new crises for future generations. So when we plan for industrial recovery, we are not simply seeking growth for growth's sake. We want an increase in the sort of economic activity which will provide real jobs, which will rebuild our decaying infrastructure, which will conserve energy, and which will re-use and recycle materials rather than wasting them. We want to invest in education and housing since our long-term future depends upon the skill and maturity of the next generation." Opposition MPs could be seen hissing and moaning, perched uncomfortably but ready for battle. The chancellor raised his head from his dispatch box to take aim. "We offer reconciliation at home and constructive leadership abroad. We are not ashamed to set our sights high."

As Mr Rodgers sat down next to the PM David Steel, he was patted on the back by roaring colleagues who deduced that his centrist spending plans had easily wrong-footed a divided Tory party eager to appear moderate and a Labour movement breaking into full-scale civil war. Shadow chancellor Peter Shore got up to respond. "This budget does little to get Britain back to work. To rebuild our shattered industries. To get rid of the ever-growing dole queues. To protect and enlarge our National Health Service and our other great social services." It was a package of criticism levelled more against insufficient extent of action rather than quality of individual measures. Alliance thinking drew heavily from the old Labour blueprint, after all; Foot and Shore needed to walk a tricky path combining socialist fury and pragmatism. He reiterated calls for £11 billion of expansion financed by debt. However captivating his rhetoric was, Mr Shore struggled to define Tribunite beliefs in the face of modest efforts in a positive direction. Next, Conservative treasury spokesman Leon Brittan (replacing Geoffrey Howe) rose to speak. "The Government made a choice today: to squander our achievements over the past four years. The answer is not bogus social contracts and overspending. Both, in the end, destroy jobs." Dry economic points fared poorly in the new House of Commons. "We did not disguise the fact that putting Britain right would be an extremely difficult task," he said. "The Government and Labour claim that they could abolish unemployment by printing or borrowing thousands of millions of pounds. This is a cruel deceit. Their plans would immediately unleash a far more savage economic crisis than their last; a crisis which would, very soon, bring more unemployment in its wake."

The emergency budget promised: an inflation tax on 'excessive' wage rises; the usage of North Sea oil revenues to fund public services; a reflationary strategy with £3 billion of raised expenditure to boost demand and generate jobs; workforce education and training; incentives for co-operatives and social enterprises; a 2% tax on the value of land; subsidies for the private sector to take on new recruits; extra healthcare funding; and capital investment, upgrading assets such as roads, bridges and homes. The Government wanted to "put spades in the ground" immediately, looking ahead to the benefits of growth across the next few years. Whilst the structural changes planned would take some time to bear fruit, 1983 might be remembered as a "turning point" when the UK decided to reject "dogma and bitterness", instead venturing on "a new road of partnership and progress". Rodgers laid out his goals as chancellor. "Our concern is for the long term, not just for tomorrow. We do not want to solve our immediate problems by piling up new crises for future generations. So when we plan for industrial recovery, we are not simply seeking growth for growth's sake. We want an increase in the sort of economic activity which will provide real jobs, which will rebuild our decaying infrastructure, which will conserve energy, and which will re-use and recycle materials rather than wasting them. We want to invest in education and housing since our long-term future depends upon the skill and maturity of the next generation." Opposition MPs could be seen hissing and moaning, perched uncomfortably but ready for battle. The chancellor raised his head from his dispatch box to take aim. "We offer reconciliation at home and constructive leadership abroad. We are not ashamed to set our sights high."

As Mr Rodgers sat down next to the PM David Steel, he was patted on the back by roaring colleagues who deduced that his centrist spending plans had easily wrong-footed a divided Tory party eager to appear moderate and a Labour movement breaking into full-scale civil war. Shadow chancellor Peter Shore got up to respond. "This budget does little to get Britain back to work. To rebuild our shattered industries. To get rid of the ever-growing dole queues. To protect and enlarge our National Health Service and our other great social services." It was a package of criticism levelled more against insufficient extent of action rather than quality of individual measures. Alliance thinking drew heavily from the old Labour blueprint, after all; Foot and Shore needed to walk a tricky path combining socialist fury and pragmatism. He reiterated calls for £11 billion of expansion financed by debt. However captivating his rhetoric was, Mr Shore struggled to define Tribunite beliefs in the face of modest efforts in a positive direction. Next, Conservative treasury spokesman Leon Brittan (replacing Geoffrey Howe) rose to speak. "The Government made a choice today: to squander our achievements over the past four years. The answer is not bogus social contracts and overspending. Both, in the end, destroy jobs." Dry economic points fared poorly in the new House of Commons. "We did not disguise the fact that putting Britain right would be an extremely difficult task," he said. "The Government and Labour claim that they could abolish unemployment by printing or borrowing thousands of millions of pounds. This is a cruel deceit. Their plans would immediately unleash a far more savage economic crisis than their last; a crisis which would, very soon, bring more unemployment in its wake."

Last edited:

"Opinion polls now show that I am best placed to recover those people who deserted us in the last election," Heseltine told reporters on 9 February. There was clearly much dissatisfaction with Mrs Thatcher but, on the other hand, she retained quite a lot of supporters. Radicals went with Tebbit; 'realists' who understood the dial had moved opted for Whitelaw. This indicates how badly the Conservative Party was split over the former Prime Minister's legacy. Discussion revolved around an MP from the younger cohort taking over. Mr Heseltine, aged 49, proposed money - including the receipts from council house sales - be spent on infrastructure projects, rejecting tax cuts as the wrong priority. He also called for reductions in tax relief on mortgage interest payments and pension contributions, in the hope of encouraging investment into industry rather than into property and finance. On the subject of long-term unemployment, he called for people to get support off benefits and into a job to reduce numbers. Tebbit clashed bitterly with Heseltine, claiming the latter's policy positions were identical to the SDP's. Nevertheless, in a few areas the two men found common ground. Both were against the devolution of powers to London and elsewhere; backed suggestions to establish market-led reforms in the NHS and fully privatise cable/wireless; opposed the mooted Freedom of Information Bill; and gleefully threw fists at Labour. According to Heseltine, Britain required a Conservative programme of industrial renewal, settling class relations without major upheaval and helping neglected towns attract private investment from large companies.

Ex-home secretary Willie Whitelaw kicked off his campaign in earnest just a fortnight before the initial round of voting was expected. As seen in leaked notes from his parliamentary tearoom chats, sympathetic MPs were told that Mr Whitelaw had "the gravest doubts" about the Task Force back in 1982, correctly fearing massive loss of life. Of course, at the time, he'd remained loyal, giving wise counsel. Figures such as Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson admired this self-styled commitment to public duty, as exhibited time and again by his protection of Thatcher in her opposition years. "The job we have is impossible," Whitelaw once told staff as Northern Ireland secretary. "So we must begin as though we are going to enjoy it." A tough approach to law and order was floated, echoing his 1979-83 tenure as home secretary. More prisons would get the green light; new grammar schools built; 10,000 extra police officers; a £3 billion annual rise in defence expenditure; income tax cuts explored; a review of the nationalised utilities; and 50% of North Seal oil channelled into a sovereign wealth fund. This manifesto succeeded in uniting a good proportion of MPs on the centre-right. When Heseltine asserted on the evening news that Thatcherism had failed the nation, both rivals announced they would not campaign for him on that basis in the next general election. Otherwise, the 64 year-old Mr Whitelaw reserved his temper for another. The feeling was mutual.

Speaking at a Monday Club event, Mr Tebbit revealed his slogan: 'The Next Move Forward'. He would have to answer misgivings surrounding his central role in the Thatcher experiment. "It's a question of leadership when our aims aren't clearly defined. When people understood what she was doing, there was a good deal of admiration for her energy and resolution and persistence - even from those who didn't agree. Now, there's a perception that we don't know where we're going." His stated aim was to present to the voters a movement "confident, united" and determined to implement change. That Lawson and co. refused to join brought a nasty disappointment. In private, Margaret Thatcher apparently told Rupert Murdoch: "I couldn't get Norman elected as leader even if I wanted - nor would the country elect him if he was". Despite this reluctance, the former PM is rumoured to have voted for Tebbit. His policies included: the sale of BT, electricity, gas, rail, steel and water; massive cuts to income and corporation tax rates; strict limits on immigration, with tight work visa checks and the requirement to speak English; a 'referendum lock' on any new EEC treaties; £5 billion of additional defence spending; and a critical friendship with the US in the aftermath of the Falklands disaster. He attracted the informal support of Ulster Unionist MP Enoch Powell, who nevertheless lambasted the Conservatives' advocacy of nuclear weapons. Whitelaw publicly denounced the Tebbit campaign. "We must be very careful to safeguard against the kind of entryism seen in the Labour Party. To have Mr Tebbit as our figurehead would be intolerable and lead us to ruin."

On 15 February, the result was announced. Heseltine won a respectable third place, given the odds. Many wets had already left the party; his candidacy was a nod to those who wanted a more liberal position and raised his standing for the future. However, the polarisation of debate revealed mounting fractures. Tebbit came in second by ably consolidating free-market zealots with traditionalists (including some 'High Tories') under one banner. Whitelaw gained a majority, topping 15% of the votes ahead of his nearest challenger, securing victory as per the rules since 1965. He told the press his triumph showed MPs were united. He immediately started assembling a frontbench team. Over half of his colleagues in Parliament had chosen stability and moderation over radicalism and further discord. Their new leader was a statesman, experienced in the art of government as well as organisational politics. His loyalty to the Conservative Party as an institution was beyond question, unlike the fidelity of a movement shattered by defeat and close to tearing itself apart. Already, there were rumblings of dissent on the right-wing fringes. How could even Whitelaw bridge the gulf between corporatist, pro-EEC Heseltine supporters, Atlantic enthusiasts, followers of Milton Friedman and imperialist race-baiters? In the glow of their election success, One Nation centrists breathed a sigh of relief that the recent ugliness was definitely over... but for how long? Time would tell.

Ex-home secretary Willie Whitelaw kicked off his campaign in earnest just a fortnight before the initial round of voting was expected. As seen in leaked notes from his parliamentary tearoom chats, sympathetic MPs were told that Mr Whitelaw had "the gravest doubts" about the Task Force back in 1982, correctly fearing massive loss of life. Of course, at the time, he'd remained loyal, giving wise counsel. Figures such as Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson admired this self-styled commitment to public duty, as exhibited time and again by his protection of Thatcher in her opposition years. "The job we have is impossible," Whitelaw once told staff as Northern Ireland secretary. "So we must begin as though we are going to enjoy it." A tough approach to law and order was floated, echoing his 1979-83 tenure as home secretary. More prisons would get the green light; new grammar schools built; 10,000 extra police officers; a £3 billion annual rise in defence expenditure; income tax cuts explored; a review of the nationalised utilities; and 50% of North Seal oil channelled into a sovereign wealth fund. This manifesto succeeded in uniting a good proportion of MPs on the centre-right. When Heseltine asserted on the evening news that Thatcherism had failed the nation, both rivals announced they would not campaign for him on that basis in the next general election. Otherwise, the 64 year-old Mr Whitelaw reserved his temper for another. The feeling was mutual.

Speaking at a Monday Club event, Mr Tebbit revealed his slogan: 'The Next Move Forward'. He would have to answer misgivings surrounding his central role in the Thatcher experiment. "It's a question of leadership when our aims aren't clearly defined. When people understood what she was doing, there was a good deal of admiration for her energy and resolution and persistence - even from those who didn't agree. Now, there's a perception that we don't know where we're going." His stated aim was to present to the voters a movement "confident, united" and determined to implement change. That Lawson and co. refused to join brought a nasty disappointment. In private, Margaret Thatcher apparently told Rupert Murdoch: "I couldn't get Norman elected as leader even if I wanted - nor would the country elect him if he was". Despite this reluctance, the former PM is rumoured to have voted for Tebbit. His policies included: the sale of BT, electricity, gas, rail, steel and water; massive cuts to income and corporation tax rates; strict limits on immigration, with tight work visa checks and the requirement to speak English; a 'referendum lock' on any new EEC treaties; £5 billion of additional defence spending; and a critical friendship with the US in the aftermath of the Falklands disaster. He attracted the informal support of Ulster Unionist MP Enoch Powell, who nevertheless lambasted the Conservatives' advocacy of nuclear weapons. Whitelaw publicly denounced the Tebbit campaign. "We must be very careful to safeguard against the kind of entryism seen in the Labour Party. To have Mr Tebbit as our figurehead would be intolerable and lead us to ruin."

On 15 February, the result was announced. Heseltine won a respectable third place, given the odds. Many wets had already left the party; his candidacy was a nod to those who wanted a more liberal position and raised his standing for the future. However, the polarisation of debate revealed mounting fractures. Tebbit came in second by ably consolidating free-market zealots with traditionalists (including some 'High Tories') under one banner. Whitelaw gained a majority, topping 15% of the votes ahead of his nearest challenger, securing victory as per the rules since 1965. He told the press his triumph showed MPs were united. He immediately started assembling a frontbench team. Over half of his colleagues in Parliament had chosen stability and moderation over radicalism and further discord. Their new leader was a statesman, experienced in the art of government as well as organisational politics. His loyalty to the Conservative Party as an institution was beyond question, unlike the fidelity of a movement shattered by defeat and close to tearing itself apart. Already, there were rumblings of dissent on the right-wing fringes. How could even Whitelaw bridge the gulf between corporatist, pro-EEC Heseltine supporters, Atlantic enthusiasts, followers of Milton Friedman and imperialist race-baiters? In the glow of their election success, One Nation centrists breathed a sigh of relief that the recent ugliness was definitely over... but for how long? Time would tell.

Last edited:

Ever since Roy Jenkins trailed the pavements of Warrington to fight its 1981 by-election, the SDP agenda had always given first concern to one item over a much-needed fix to unemployment. Before tackling the dole queue, they would have to formulate a system of price and wage controls to bring down inflation. The Alliance promoted this despite Heathite and Owenite concerns. Although some in the new Government looked unkindly on previous mechanisms from the Wilson and Callaghan days, Jenkins and Bill Rodgers held firm with Liberal support. Reviving the 'social contract' inspired by Nixon's US administration in the 1970s, trade unions would accept very limited wage growth and prices would be restrained by businesses. Nationalised bodies would follow a similar line. Through a Pay and Prices Commission, trade secretary John Pardoe discussed with representatives of business, unions and consumers, the desirable range for wage negotiations. Pay settlements in large firms were monitored, with Government powers to restrict increases above the agreed range; this exempted small companies. Set alongside the Counter-Inflation Tax levied by Inland Revenue on high wage rises, better productivity in firms would be allowed to translate into pay rewards via allocation of (initially non-marketable) shares. However, for now the Government carried out a fully statutory incomes policy.

On the global stage, Alliance ministers hoped to design a progressive, modern role for Britain. Mr Jenkins (formerly European Commission President) favoured closer ties with the UK's neighbours. This won the backing of David Steel and Shirley Williams, cementing his influence. Most Liberal and SDP members identified with the project of European federalism, the 'good old cause' for severed relations with Michael Foot's Labour. Integration symbolised the direction of travel - for cooperation, reform and peace; against isolation and division. Opponents questioned this framing given matters of democracy, sovereignty and overreach by the banking class in Europe. Either way, Mr Steel believed that the issue had been closed by referendum in 1975; he would press ahead. Britain joined the European Monetary System (EMS) on 13 March 1983 - four years after its creation - with existing members France, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. Foreign secretary David Owen also spearheaded membership of the European Currency Unit, a measure to price some financial transactions and capital transfers. London would assist in providing exchange rate stability on the Continent, echoing the Keynesian 'Bretton Woods' mechanism of 1944-76. Mr Owen realised that German monetary policy dominance was because of that nation's high GDP growth rate and low inflation. The UK's response was to task Bank of England planners with its own version at home.

British submarines had been circling the Falkland Islands for nine months, denying access to Argentine goods, ships, aircraft and men. RAF planes continued to bomb enemy defences at long range from the Wideawake base on Ascension Island, an operation known as Black Buck. This airport was, over the course of 1982, the busiest in the world in terms of movements. Port Stanley and other targets underwent heavy damage in the lead up to March 1983, when the Alliance Government began negotiations with Junta officials to end the undeclared conflict and organise a peace deal. Since the failure of the 1956 Suez Campaign, the end of Empire and economic decline in the 1970s which culminated in the Winter of Discontent, Britain had been beset by uncertainty and anxiety about its international role, status and capability. With defeat, her 'special relationship' with America was strained, weakening their unity of resolve against the Soviet Union. The Junta soon eyed border adjustments with Chile, dizzied by victory over a colonial power and riding a wave of nationalist frenzy. Flying to Buenos Aires, UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar chaired a summit on 21 March. Diplomats met with him over lunch, followed by an introduction of Steel and Owen to Argentine president Leopoldo Galtieri.

Mr Owen did not share the ambivalence to British power projection in the South Atlantic held by many Westminster colleagues. He had wanted the UK to win and hated the incompetence displayed by Thatcher in allowing an invasion to start with. Naval rearmament was finishing completion, a development which threatened Argentine control. Getting down to talks, the Foreign Secretary agreed that British rule would not ensure a lasting solution to the dispute and offered a compromise settlement. Under a trusteeship, sovereignty would be transferred to the UN. Administration of the islands would be passed from Britain to Argentina under UN supervision. Failure of the Junta to engage in this process would incur the wrath of Task Force 2, having learned from its predecessor. Only a fair outcome for both sides could be sustained politically, while military alternatives existed. The British really only cared that the islanders were not deprived of their rights. Moreover, the Argentines were still willing to forego actual control as long as the British dropped their claim to sovereignty over the Malvinas. The UN trusteeship would prevent abuses of human rights and encourage political, social and economic reconstruction. Galtieri signed up to the plan, happy with the victory he'd accomplished.

For Argentina, the advantage of UN supervision was that it provided administrative control of the islands for an indefinite period. The UK would immediately yield sovereignty. However, since Las Malvinas would be classified as a strategic trust, final disposition of the issue would be determined by the Security Council - where Britain exercised a veto. A ceasefire came into effect on 25 March. The next day, US papers described it as a "good investment in world order". Jubilant crowds amassed in Buenos Aires, waving flags in scenes reminiscent of mid-1982. While British public opinion was less than comfortable with this, surveys indicated that a majority felt glad the entire sorry mess was over. Dreams of ruling the waves had gone; the UK would have to reemerge a different, more forward-facing country among equals.

On the global stage, Alliance ministers hoped to design a progressive, modern role for Britain. Mr Jenkins (formerly European Commission President) favoured closer ties with the UK's neighbours. This won the backing of David Steel and Shirley Williams, cementing his influence. Most Liberal and SDP members identified with the project of European federalism, the 'good old cause' for severed relations with Michael Foot's Labour. Integration symbolised the direction of travel - for cooperation, reform and peace; against isolation and division. Opponents questioned this framing given matters of democracy, sovereignty and overreach by the banking class in Europe. Either way, Mr Steel believed that the issue had been closed by referendum in 1975; he would press ahead. Britain joined the European Monetary System (EMS) on 13 March 1983 - four years after its creation - with existing members France, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. Foreign secretary David Owen also spearheaded membership of the European Currency Unit, a measure to price some financial transactions and capital transfers. London would assist in providing exchange rate stability on the Continent, echoing the Keynesian 'Bretton Woods' mechanism of 1944-76. Mr Owen realised that German monetary policy dominance was because of that nation's high GDP growth rate and low inflation. The UK's response was to task Bank of England planners with its own version at home.

British submarines had been circling the Falkland Islands for nine months, denying access to Argentine goods, ships, aircraft and men. RAF planes continued to bomb enemy defences at long range from the Wideawake base on Ascension Island, an operation known as Black Buck. This airport was, over the course of 1982, the busiest in the world in terms of movements. Port Stanley and other targets underwent heavy damage in the lead up to March 1983, when the Alliance Government began negotiations with Junta officials to end the undeclared conflict and organise a peace deal. Since the failure of the 1956 Suez Campaign, the end of Empire and economic decline in the 1970s which culminated in the Winter of Discontent, Britain had been beset by uncertainty and anxiety about its international role, status and capability. With defeat, her 'special relationship' with America was strained, weakening their unity of resolve against the Soviet Union. The Junta soon eyed border adjustments with Chile, dizzied by victory over a colonial power and riding a wave of nationalist frenzy. Flying to Buenos Aires, UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar chaired a summit on 21 March. Diplomats met with him over lunch, followed by an introduction of Steel and Owen to Argentine president Leopoldo Galtieri.

Mr Owen did not share the ambivalence to British power projection in the South Atlantic held by many Westminster colleagues. He had wanted the UK to win and hated the incompetence displayed by Thatcher in allowing an invasion to start with. Naval rearmament was finishing completion, a development which threatened Argentine control. Getting down to talks, the Foreign Secretary agreed that British rule would not ensure a lasting solution to the dispute and offered a compromise settlement. Under a trusteeship, sovereignty would be transferred to the UN. Administration of the islands would be passed from Britain to Argentina under UN supervision. Failure of the Junta to engage in this process would incur the wrath of Task Force 2, having learned from its predecessor. Only a fair outcome for both sides could be sustained politically, while military alternatives existed. The British really only cared that the islanders were not deprived of their rights. Moreover, the Argentines were still willing to forego actual control as long as the British dropped their claim to sovereignty over the Malvinas. The UN trusteeship would prevent abuses of human rights and encourage political, social and economic reconstruction. Galtieri signed up to the plan, happy with the victory he'd accomplished.

For Argentina, the advantage of UN supervision was that it provided administrative control of the islands for an indefinite period. The UK would immediately yield sovereignty. However, since Las Malvinas would be classified as a strategic trust, final disposition of the issue would be determined by the Security Council - where Britain exercised a veto. A ceasefire came into effect on 25 March. The next day, US papers described it as a "good investment in world order". Jubilant crowds amassed in Buenos Aires, waving flags in scenes reminiscent of mid-1982. While British public opinion was less than comfortable with this, surveys indicated that a majority felt glad the entire sorry mess was over. Dreams of ruling the waves had gone; the UK would have to reemerge a different, more forward-facing country among equals.

Last edited:

David Steel encountered plaudits and blame in the House of Commons during Prime Minister's Question Time on 29 March. John Golding had been agreed unanimously to become Speaker, technically cutting the Labour ranks to 189. Opposition leader Michael Foot, who'd supported the 40,000-strong Task Force, used every chance to savage the Government over losing the Falklands. Defeat undermined the UK's "great power" status and with it, he argued belligerently, influence that could be used to promote justice and disarmament. Foot highlighted the rights of the islanders, who wished to stay British. "We have surrendered our moral duty", he said regretfully. Most fellow comrades to his left delighted in the retreat of empire. Yet the Labour leader viewed the Junta's actions as unwarranted fascist aggression, which had now been "rewarded" by success. In a bid to unite the disparate tribes of his rancorous party, Mr Foot voiced his consistent support for the principle of a UN-brokered treaty. On the one hand, his commitment to anti-appeasement and democratic socialism led him to oppose Argentina's land grab, while conversely, Foot felt anxious over parallels with the Suez Crisis, which he had so forcefully condemned as editor of Tribune magazine. Within the shadow cabinet, NEC and trade unions, Foot paradoxically relied upon the support of moderates and revisionists engaged in bitter anti-left conflict to bolster him on the issue. Defectors now in ministerial positions, including Roy Hattersley and Giles Radice, ridiculed Labour as wallowing in unpatriotic "moral gestures" and "mock heroics". Shadow chancellor Peter Shore, himself a kind of nationalist, doubled down on Foot's stance. Tony Benn, in a barnstorming speech that day in Parliament, contended that the war had been in vain and fought mainly for the pursuit of oil, its "real interest". His faction viewed the episode as seeking to revive militaristic and xenophobic attitudes. Neil Kinnock, thought of as a Bennite since the 1981 deputy leadership race, now commended the use of fleet upgrades as a bargaining chip to achieve peace. Veteran socialist Ian Mikardo repeated his call for the UK to abandon America and forge a European defence pact. In the words of anti-war journalist Chris Mullin, Foot had been "carried away by [the] tide of revived imperialist fervour". The weakened Labour leader responded by condemning the Bennites' "infantile leftism".

Only by securing a trusteeship had the Alliance managed to curb both waves of media-generated jingoism and hopelessness sweeping Britain. If Labour's fractures appeared unmanageable, the Conservatives were yet to recover from Thatcher's failed strategy to link attempted reconquest in the Falklands with efforts to overturn the post-war consensus. With defeat on the high seas, electoral ruin and the substitution of Liberal and SDP ministers for loser Tories, the party's New Right faced withdrawal from public relevance as the narrative changed. In the place of Britain's empire was a Euro-federalist country renewed in favour of multilateral answers to collective security. America, once her leading partner, was looked at with distrust by angry patriots and socialists alike. The Prime Minister's cohort tried hard to prop up the Atlantic relationship, pitching London as the ideal diplomatic and trading post for Brussels and Washington. In the Commons, he exploited divisions. Mrs Thatcher had sought to use the courage of British troops "for the greater glory of herself". Conservatives "presided over a shambles of incompetence" in their conduct of foreign policy, hiding their administration's "nakedness" with the flag. Mr Steel turned his attention to the Labour leader. "Mr Speaker, the Labour Party have taken leave of their senses. The Right Honourable Gentleman's attack was quite extraordinary. I suppose it just demonstrates the panic in Labour ranks. Desperation has set in." In the nation at large, a majority seemed to endorse the Government. Polls averaged the Liberals/SDP on 51%, Conservatives 27% and Labour 21%. The Alliance were given credit for ending the war and stood insurmountable above factious rivals. Opposition MPs sank into dismay. Norman Tebbit, who'd declined to join Willie Whitelaw's team after being refused the post of home affairs spokesman, urged other Thatcherites to cause havoc in a bid to discredit One Nation centrists and break the unity leadership's stability. For this, Mr Tebbit cynically appealed to parliamentarians and the voters, calling for a tougher line on defence and immigration. He also lambasted Whitelaw's preference for economic subsidies as "unnatural restrictions on the free market". The PM was tempted to call a snap general election, hoping to increase the Government's majority of seats; other Liberals worried about losing their party's primacy in the Coalition Government. Fears were corroborated by evidence that a higher vote share for the Alliance would result in mostly SDP wins in Labour constituencies. Even a handful of gains for Shirley Williams' party could put her in 10 Downing Street as head of the largest Alliance member. This is not to say the two leaders' partnership was strained: they worked rather harmoniously. Steel ruled out another election in a press conference, denouncing the 'first past the post' (FPTP) voting system as "outdated and on borrowed time". Radical reforms would follow.

Only by securing a trusteeship had the Alliance managed to curb both waves of media-generated jingoism and hopelessness sweeping Britain. If Labour's fractures appeared unmanageable, the Conservatives were yet to recover from Thatcher's failed strategy to link attempted reconquest in the Falklands with efforts to overturn the post-war consensus. With defeat on the high seas, electoral ruin and the substitution of Liberal and SDP ministers for loser Tories, the party's New Right faced withdrawal from public relevance as the narrative changed. In the place of Britain's empire was a Euro-federalist country renewed in favour of multilateral answers to collective security. America, once her leading partner, was looked at with distrust by angry patriots and socialists alike. The Prime Minister's cohort tried hard to prop up the Atlantic relationship, pitching London as the ideal diplomatic and trading post for Brussels and Washington. In the Commons, he exploited divisions. Mrs Thatcher had sought to use the courage of British troops "for the greater glory of herself". Conservatives "presided over a shambles of incompetence" in their conduct of foreign policy, hiding their administration's "nakedness" with the flag. Mr Steel turned his attention to the Labour leader. "Mr Speaker, the Labour Party have taken leave of their senses. The Right Honourable Gentleman's attack was quite extraordinary. I suppose it just demonstrates the panic in Labour ranks. Desperation has set in." In the nation at large, a majority seemed to endorse the Government. Polls averaged the Liberals/SDP on 51%, Conservatives 27% and Labour 21%. The Alliance were given credit for ending the war and stood insurmountable above factious rivals. Opposition MPs sank into dismay. Norman Tebbit, who'd declined to join Willie Whitelaw's team after being refused the post of home affairs spokesman, urged other Thatcherites to cause havoc in a bid to discredit One Nation centrists and break the unity leadership's stability. For this, Mr Tebbit cynically appealed to parliamentarians and the voters, calling for a tougher line on defence and immigration. He also lambasted Whitelaw's preference for economic subsidies as "unnatural restrictions on the free market". The PM was tempted to call a snap general election, hoping to increase the Government's majority of seats; other Liberals worried about losing their party's primacy in the Coalition Government. Fears were corroborated by evidence that a higher vote share for the Alliance would result in mostly SDP wins in Labour constituencies. Even a handful of gains for Shirley Williams' party could put her in 10 Downing Street as head of the largest Alliance member. This is not to say the two leaders' partnership was strained: they worked rather harmoniously. Steel ruled out another election in a press conference, denouncing the 'first past the post' (FPTP) voting system as "outdated and on borrowed time". Radical reforms would follow.

Last edited:

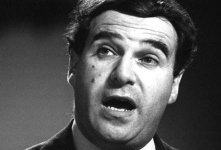

After coming third at the ballot box and second in Parliament, Labour entered 1983 with heavy weight on their minds. Most discussions produced furious wrangling between tribes; few invited unity. In any case, MPs were distracted by the viciousness of a civil war stretching from the grassroots up to senior leadership. The Wilson and Callaghan ministries from 1964-70 and 1974-79 included much to be proud of; however, disappointments (particularly for the left) emerged as the party, headed predominantly by members of the trade unionist right, fell to monetarism in seeking a bail-out from the IMF. This, against a background of industrial militancy and class conflict. Workers, bargaining for fairer pay and conditions, had only elected union representatives to negotiate with the Government. Actual workplace democracy barely existed. The state-owned bodies were still structured along capitalist lines of production, concentrating decision-making power in the hands of a minority. Higher inflation, triggered by the rocketing price of Middle Eastern oil, tore into family budgets. Under Harold Wilson, Labour tried to enact a union-led policy of voluntary wage restraint in a bid to lower the spike. In return, the Government repealed Ted Heath's Conservative legislation on industrial relations, froze rent increases and introduced food subsidies. Known as the 'Social Contract', different individual groups could be treated separately by an employer (in publicly owned bodies, the state) when devising pay settlements. This allowed for a degree of flexibility, unlike the previous mechanism. Wages would be decided annually, taking into account the wish to offset expected or recent inflation rises. By the end of Jim Callaghan's time in office, the contract was breaking down because of competing demands from workers and bosses, falling profits (amid industrial decline) and stubbornly high prices. The 1978 'Winter of Discontent' stuck in voters' minds, causing many to abandon Labour and elect Margaret Thatcher, whose rhetoric exploited the situation and moved Britain away from organised industrial action. Now in opposition, radical socialists blamed their party's elite for failing to carry out its manifesto pledges, accusing the failed administrations of being weak and timid. Allies of Callaghan balked at the expansion of a mass membership hungry for democratic involvement, political boldness and revenge on the right.

Michael Foot's disastrous time at the helm can be attributed to several factors: his often clumsy appearance and old-fashioned delivery, seized upon by the Tory press; desertion by a good deal of the Labour moderates, carping from the sidelines or joining the SDP; brutal infighting among centrists and Tony Benn, whose victory in the deputy leadership race saw tensions burst into the public arena; and the superior tactical nous of (at first) Thatcher, followed by David Steel and Shirley Williams. The contrast between Labour - intent on sweeping nationalisation, abolition of the Lords and withdrawal from the EEC - and the Alliance meant that, in the context of an exodus of supporters leaving the Conservatives over issues of defence and the economy, millions of swing voters found a home with the Liberals and SDP. Foot, by now, had lost credibility over the Falklands. The Keynesian post-war consensus built by Attlee's reforming administration was struggling to mend a divided nation, pulled apart by capitalism in crisis. Responsibility for this endeavour no longer sat in the hands of Labour, but with Alliance ministers. Everyone in Foot's party resorted to old feuds in search of blame. Calling a leadership election to be held right after May Day, the party's 'broad church' arrived at a violent schism. First to lay out his stall was Mr Benn. He promised to transform Labour, harnessing the eagerness of grassroots supporters right across the land to disperse power, ensuring that policies agreed by conference held sway over future governments. MPs would undergo a mandatory, open re-selection process in front of local members to provide accountability. In charge of the British state, Labour would widely extend democratic social ownership of the towering heights of industry. At last, ordinary employees could actually run their firms with strong rights, the ability to elect managers from among their ranks and collective allocation of profits. A "national liberation struggle" aimed at working-class voters promised to free the people from monarchy, European capitalism and American hegemony. Echoing the 1974 manifesto, Benn vowed that his leadership meant an "irreversible shift of the balance of power in favour of workers and their families". Britain would be refashioned as a socialist commonwealth, following a decisive move to the left.

Even with many right-wingers having crossed the floor, resistance to Benn's vision was deep and enduring. Keen to avenge his narrow defeat in 1981 and move on from Foot, 'big beast' Denis Healey declared his intention to challenge for the leadership. However, he remained reluctant to publicly disregard mandatory re-selection or the electoral college. Far from rallying the centre over dividing lines such as nuclear weapons or Europe, Healey tried to placate wavering socialists by coming across as inoffensive. In his eyes, the unions could handle internal debates while a project of the Labour right would focus on winning a majority irrespective of policy commitments. While this failed to inspire the most ardent anti-Bennites, his mild-mannered approach succeeded in keeping elements of the 'soft left' on board. Healey believed that the likes of Gerald Kaufman and Eric Varley had nowhere else to go but to endorse him. It was a risky bet. The left now exercised control over policy and internal organisation. Without someone like Roy Hattersley there to find a compromise, Labour descended into open conflict. Foreign secretary David Owen lamented his former party's abandoning of the mixed economy, internationalism and parliamentary oversight. Peter Shore decided to run for the leadership on a pro-nuclear, anti-EEC ticket. The contest began in earnest straight away: Benn, on screens and touring the country for rallies and pickets; Healey, trading jibes and working to dispel his aloof reputation. The left had "thrown away" dreams of success in 1983 by fracturing the party, he claimed. Benn attacked the right, particularly SDP splitters, telling crowds his leadership would back unilateral disarmament, exit from the Common Market, a 35-hour week without loss of pay, rejection of an incomes policy and a "fully socialised economy" founded on democratic ownership. Party conference affirmed this programme. Although they were losing ground, the right retained influence in the unions and, of course, among MPs. Pitched in a fight over democracy, those supporting an elitist position could not hope to persuade the membership.

On 2 May, a special assembly played host to the results announcement. First, the outcome of the deputy leadership contest was read out. Neil Kinnock, an 'independent socialist' from Wales who had begun to distance himself from the radical left, secured a convincing victory in the second round. Michael Meacher, Benn's "vicar on Earth" was the runner-up, beating Kaufman whose moderate social democratic campaign got limited sway. Eric Heffer, another Bennite, came fourth. Soft left, anti-war candidate Tam Dalyell picked up loyal followers across the party spectrum, winning fifth place. Gwyneth Dunwoody, who'd run on a ticket with Peter Shore, fell in last. Kinnock's election was a decent result for the post-Bevan centre-left. He appealed to Labour members in the north of England and Wales, moderate socialists and less ideological pragmatists longing for unity. If the tussle for deputy replicated Foot's Tribunite victory in 1980, the main event set new precedents. In one ballot, made up of 40% for the union block vote, 30% for constituency parties and 30% MPs, the left triumphed. Mr Benn stormed to victory by 5% over Healey. Shore took a disappointing bronze, reflecting his part in fiasco as shadow chancellor. Right-wing members were completely appalled and despairing. MPs soon convened to discuss their next steps. The grassroots, who numbered 300,000 at this point, voted overwhelmingly for Benn to change the party and fight to usher in a different dawn for Britain. Standing before the conference, Labour's new leader identified "the rebirth of hope in people", bombastically taking turns to rail against the obstacle of unelected peers, a record 3 million unemployed, the plight of welfare services and looming nuclear war. Benn told members that day: a left-wing movement fronted by him would rise to the economic, social and political challenges facing voters.

Michael Foot's disastrous time at the helm can be attributed to several factors: his often clumsy appearance and old-fashioned delivery, seized upon by the Tory press; desertion by a good deal of the Labour moderates, carping from the sidelines or joining the SDP; brutal infighting among centrists and Tony Benn, whose victory in the deputy leadership race saw tensions burst into the public arena; and the superior tactical nous of (at first) Thatcher, followed by David Steel and Shirley Williams. The contrast between Labour - intent on sweeping nationalisation, abolition of the Lords and withdrawal from the EEC - and the Alliance meant that, in the context of an exodus of supporters leaving the Conservatives over issues of defence and the economy, millions of swing voters found a home with the Liberals and SDP. Foot, by now, had lost credibility over the Falklands. The Keynesian post-war consensus built by Attlee's reforming administration was struggling to mend a divided nation, pulled apart by capitalism in crisis. Responsibility for this endeavour no longer sat in the hands of Labour, but with Alliance ministers. Everyone in Foot's party resorted to old feuds in search of blame. Calling a leadership election to be held right after May Day, the party's 'broad church' arrived at a violent schism. First to lay out his stall was Mr Benn. He promised to transform Labour, harnessing the eagerness of grassroots supporters right across the land to disperse power, ensuring that policies agreed by conference held sway over future governments. MPs would undergo a mandatory, open re-selection process in front of local members to provide accountability. In charge of the British state, Labour would widely extend democratic social ownership of the towering heights of industry. At last, ordinary employees could actually run their firms with strong rights, the ability to elect managers from among their ranks and collective allocation of profits. A "national liberation struggle" aimed at working-class voters promised to free the people from monarchy, European capitalism and American hegemony. Echoing the 1974 manifesto, Benn vowed that his leadership meant an "irreversible shift of the balance of power in favour of workers and their families". Britain would be refashioned as a socialist commonwealth, following a decisive move to the left.

Even with many right-wingers having crossed the floor, resistance to Benn's vision was deep and enduring. Keen to avenge his narrow defeat in 1981 and move on from Foot, 'big beast' Denis Healey declared his intention to challenge for the leadership. However, he remained reluctant to publicly disregard mandatory re-selection or the electoral college. Far from rallying the centre over dividing lines such as nuclear weapons or Europe, Healey tried to placate wavering socialists by coming across as inoffensive. In his eyes, the unions could handle internal debates while a project of the Labour right would focus on winning a majority irrespective of policy commitments. While this failed to inspire the most ardent anti-Bennites, his mild-mannered approach succeeded in keeping elements of the 'soft left' on board. Healey believed that the likes of Gerald Kaufman and Eric Varley had nowhere else to go but to endorse him. It was a risky bet. The left now exercised control over policy and internal organisation. Without someone like Roy Hattersley there to find a compromise, Labour descended into open conflict. Foreign secretary David Owen lamented his former party's abandoning of the mixed economy, internationalism and parliamentary oversight. Peter Shore decided to run for the leadership on a pro-nuclear, anti-EEC ticket. The contest began in earnest straight away: Benn, on screens and touring the country for rallies and pickets; Healey, trading jibes and working to dispel his aloof reputation. The left had "thrown away" dreams of success in 1983 by fracturing the party, he claimed. Benn attacked the right, particularly SDP splitters, telling crowds his leadership would back unilateral disarmament, exit from the Common Market, a 35-hour week without loss of pay, rejection of an incomes policy and a "fully socialised economy" founded on democratic ownership. Party conference affirmed this programme. Although they were losing ground, the right retained influence in the unions and, of course, among MPs. Pitched in a fight over democracy, those supporting an elitist position could not hope to persuade the membership.

On 2 May, a special assembly played host to the results announcement. First, the outcome of the deputy leadership contest was read out. Neil Kinnock, an 'independent socialist' from Wales who had begun to distance himself from the radical left, secured a convincing victory in the second round. Michael Meacher, Benn's "vicar on Earth" was the runner-up, beating Kaufman whose moderate social democratic campaign got limited sway. Eric Heffer, another Bennite, came fourth. Soft left, anti-war candidate Tam Dalyell picked up loyal followers across the party spectrum, winning fifth place. Gwyneth Dunwoody, who'd run on a ticket with Peter Shore, fell in last. Kinnock's election was a decent result for the post-Bevan centre-left. He appealed to Labour members in the north of England and Wales, moderate socialists and less ideological pragmatists longing for unity. If the tussle for deputy replicated Foot's Tribunite victory in 1980, the main event set new precedents. In one ballot, made up of 40% for the union block vote, 30% for constituency parties and 30% MPs, the left triumphed. Mr Benn stormed to victory by 5% over Healey. Shore took a disappointing bronze, reflecting his part in fiasco as shadow chancellor. Right-wing members were completely appalled and despairing. MPs soon convened to discuss their next steps. The grassroots, who numbered 300,000 at this point, voted overwhelmingly for Benn to change the party and fight to usher in a different dawn for Britain. Standing before the conference, Labour's new leader identified "the rebirth of hope in people", bombastically taking turns to rail against the obstacle of unelected peers, a record 3 million unemployed, the plight of welfare services and looming nuclear war. Benn told members that day: a left-wing movement fronted by him would rise to the economic, social and political challenges facing voters.

Last edited:

Over the course of Spring, the Coalition Government used both rival parties' turmoil for its advantage. Launching a package of bills introduced in the Queen's Speech to Parliament, Commons leader David Alton outlined the Alliance's goals. With the "fair and effective" wages and prices system up and running, the February budget's £3 billion emergency spending could be invested to reduce unemployment by 1 million during the next two years. This situation, caused by "strife in British industry, restrictive practices and low investment", was of utmost priority. A series of motions would be voted on to approve key policy changes. First, defence secretary Russell Johnston confirmed that Trident, the planned upgrade from Britain's Polaris nuclear weapons system, would be cancelled. Revenues saved would help to fund the Government's jobs programme, alongside borrowing. In spite of reservations held by those such as Liberal David Penhaligon and quite a few SDP folk, Parliament ratified the move by 405 'ayes' to 232 'nays', a thumping majority of 173. This included the Government's 327 MPs, together with 69 pacifists from Labour, 5 SNP, 3 Plaid Cymru and 1 SDLP. The UUP, influenced by Enoch Powell, chose to abstain. Sinn Féin's only MP did not take his seat to vote. Celebrating a win, David Steel and colleagues immediately published their landmark legislation. While Benn found broad praise across the left, ranging all the way to Barbara Castle in the European Parliament, many opponents inside Labour lambasted his "siege economy" financial policy. Rejecting Benn's Labour leadership success and the advance of Trotskyist group Militant, fifteen names from the party's right and centre defected to the SDP. These were: Leo Abse, Donald Anderson, Peter Archer, Tony Blair, Betty Boothroyd, Gordon Brown, Ian Campbell, Donald Dewar, Andrew Faulds, George Foulkes, Denis Howell, Roy Mason, George Robertson, Robert Sheldon and James White. It was another triumph for the Alliance. Mr Steel had bottled a snap election over fear that he'd lose the premiership to Shirley Williams; now, her party counted 177 MPs over 165 Liberals. The Coalition's majority increased from 4 to 34. No challenge to the PM would arise, yet the balance of power inside the Government favoured Social Democrats. At the very least, an equal relationship between the two Alliance parties (covering ministerial positions and policy) was secure. Steel could not govern wholly as he pleased - every single decision would need to be thrashed out with the Gang of Four.

Debates on the legislation presented before Parliament started off in the House of Commons. One flagship item was the Education and Training Bill, drafted by the minister responsible, Roy Hattersley. This put forward an extension of the Youth Training Scheme to all 16 and 17 year olds, including provisions over the long term for everyone aged 16-19 to receive the opportunity of either student work experience or a job with access to skills development. Adversaries tried to vote down the bill while Labour were divided, hence it progressed with 446 (generally pro-Keynesian) MPs in favour and 202 (socialists and Conservatives) against: a majority of 244. Liberal Des Wilson and Social Democrat Giles Radice jointly pioneered the wide-ranging Environment, Housing and Public Investment Bill. Through a huge expansion of the Community Programme, the Government planned to target construction jobs on the long-term out of work. Of particular focus would be regions of high unemployment figures. £500 million would be earmarked for vacancies in the NHS and social services. Altogether, the Coalition intended to boost demand with public works, reflating the economy to raise GDP growth and uplift household incomes. The bill passed its initial stages through the Commons with 437 ayes (mainly SDP, Liberals and the Labour right) vs 211 nays. Next came the controversial Trade Union Reform Bill. Employment secretary Richard Wainwright, Liberal treasury spokesman prior to the 1983 general election, introduced his draft legislation with a pledge to make unions "genuinely representative of their members". The Alliance foresaw organised labour playing an important role in a new system of employee democracy. "We want to see effective... and responsible trade unions playing their full part in industry, and in this we stand apart from the Conservative Party." Benn and supporters jeered from the opposite benches. The bill legislated to provide for: compulsory secret individual ballots for the election of union leaders; the right for 10% of a bargaining unit to require a vote before calling a strike; mandatory arbitration talks to end disputes in essential public services, before industrial action can commence; tax exemption for union contributions to encourage a higher level of funding; a Development Fund to assist trade union mergers and rationalisation; access to organise in workplaces; and an Employees' Charter, clearly safeguarding union freedoms.