Hi everyone!

In the wake of recent drafts and learning to create wiki infoboxes, I've decided to organise this alt-history into a final, proper timeline, complete with media and quotations. Our story follows Britain under the divisive rule of Maggie Thatcher, Labour's conversion to full-blooded socialism and the ascendancy of a new, radical centre: the SDP-Liberal Alliance. My work aims to tell what happened in much greater detail, so might take a while to unfold - our goal is to cover a world shaped by events all the way until the present day. Prepare for changed realities, a shock to political fortunes and the UK's very nature to be dramatically different by the end of it! Thanks for reading

So here goes -

BREAKING THE MOULD REDUX:

A Wikibox Timeline

On 4th May 1979, the United Kingdom awoke to news of a change of government. Having conducted polling across the land, Labour were out and the Conservatives, for the first time in five years, were in. Britain swung decisively to a fresh kind of Toryism, more classical free markets than post-war moderation. Under Margaret Thatcher, the country had a woman leader and the mandate to introduce policies to end a consensus in effect since 1945.

Her objectives were rebuilding economic prosperity, limiting trade union freedoms and transforming the soul of the nation. At the steps to 10 Downing Street, the incoming prime minister quoted St Francis of Assisi: "Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope".

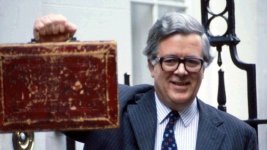

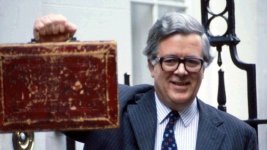

Mrs Thatcher's cabinet included faces from left and right of the party quite evenly, with several millionaires, old Etonians and hereditary peers. The chancellor, Geoffrey Howe, asserted that both borrowing and spending were too high and, in order to reduce inflation, must be reduced. The indicators looked negative; unemployment was also rising. In his budget, public expenditure and direct taxation would be cut, while the indirect value-added tax (VAT) rose substantially. Moving the burden of taxation, distributive role of the state and balance of power in the country at large - from workers to employers and in favour of individuals - became the government's driving missions.

By early 1980, inflation had actually doubled to 21.8% since Labour left office. This was a recurring problem catalysed by shocks to oil prices in the 1970s. The unions, hoping to prevent their members taking the brunt of spiralling prices, fought collectively for wage increases, which grew by 20.1% in the same period. Howe's response was paired to high interest and exchange rates; with a manufacturing sector in trouble, forecasts were bleak. As some of the media and Conservatives talked of a 'wage-price spiral', petrol's shrinking affordability thanks to price gouging and market forces in the OAPEC zone really hit working-class Brits in their pockets. Thatcher espoused 'sound finances': handling the economy as a household budget, to be trimmed of anything deemed wasteful, such as badly run or loss-making industries and even jobs.

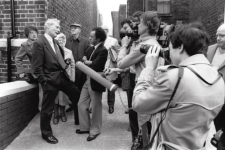

As ship-building and steel fell to the gods of monetarism, outcries across the country against its so-called 'Iron Lady' were palpable. Jobless numbers topped 2 million that year, with grim consequences for family incomes, poverty and life chances. Britain was entering a recession. The Tory left, represented by Ted Heath, Jim Prior etc held misgivings about the course of economic policy. Damaging leaks to the press added to a narrative of Keynesian 'wets' vs Thatcherite 'dries'. Against this backdrop of turmoil, the prime minister took to her stage at the 1980 Conservative Party conference to send a resolute message: "To those waiting with baited breath for that favourite media catchphrase, the U-turn, I have only one thing to say: you turn if you want to; the lady's not for turning".

In the wake of recent drafts and learning to create wiki infoboxes, I've decided to organise this alt-history into a final, proper timeline, complete with media and quotations. Our story follows Britain under the divisive rule of Maggie Thatcher, Labour's conversion to full-blooded socialism and the ascendancy of a new, radical centre: the SDP-Liberal Alliance. My work aims to tell what happened in much greater detail, so might take a while to unfold - our goal is to cover a world shaped by events all the way until the present day. Prepare for changed realities, a shock to political fortunes and the UK's very nature to be dramatically different by the end of it! Thanks for reading

So here goes -

BREAKING THE MOULD REDUX:

A Wikibox Timeline

On 4th May 1979, the United Kingdom awoke to news of a change of government. Having conducted polling across the land, Labour were out and the Conservatives, for the first time in five years, were in. Britain swung decisively to a fresh kind of Toryism, more classical free markets than post-war moderation. Under Margaret Thatcher, the country had a woman leader and the mandate to introduce policies to end a consensus in effect since 1945.

Her objectives were rebuilding economic prosperity, limiting trade union freedoms and transforming the soul of the nation. At the steps to 10 Downing Street, the incoming prime minister quoted St Francis of Assisi: "Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope".

Mrs Thatcher's cabinet included faces from left and right of the party quite evenly, with several millionaires, old Etonians and hereditary peers. The chancellor, Geoffrey Howe, asserted that both borrowing and spending were too high and, in order to reduce inflation, must be reduced. The indicators looked negative; unemployment was also rising. In his budget, public expenditure and direct taxation would be cut, while the indirect value-added tax (VAT) rose substantially. Moving the burden of taxation, distributive role of the state and balance of power in the country at large - from workers to employers and in favour of individuals - became the government's driving missions.

By early 1980, inflation had actually doubled to 21.8% since Labour left office. This was a recurring problem catalysed by shocks to oil prices in the 1970s. The unions, hoping to prevent their members taking the brunt of spiralling prices, fought collectively for wage increases, which grew by 20.1% in the same period. Howe's response was paired to high interest and exchange rates; with a manufacturing sector in trouble, forecasts were bleak. As some of the media and Conservatives talked of a 'wage-price spiral', petrol's shrinking affordability thanks to price gouging and market forces in the OAPEC zone really hit working-class Brits in their pockets. Thatcher espoused 'sound finances': handling the economy as a household budget, to be trimmed of anything deemed wasteful, such as badly run or loss-making industries and even jobs.

As ship-building and steel fell to the gods of monetarism, outcries across the country against its so-called 'Iron Lady' were palpable. Jobless numbers topped 2 million that year, with grim consequences for family incomes, poverty and life chances. Britain was entering a recession. The Tory left, represented by Ted Heath, Jim Prior etc held misgivings about the course of economic policy. Damaging leaks to the press added to a narrative of Keynesian 'wets' vs Thatcherite 'dries'. Against this backdrop of turmoil, the prime minister took to her stage at the 1980 Conservative Party conference to send a resolute message: "To those waiting with baited breath for that favourite media catchphrase, the U-turn, I have only one thing to say: you turn if you want to; the lady's not for turning".