NotDavidSoslan

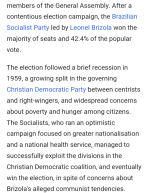

Active member

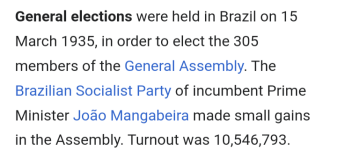

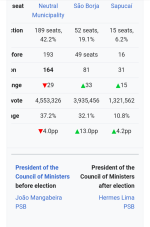

In August 1889, the Brazilian General Assembly passed several reforms, which historians credit with preventing a republican coup d'etat and the overthrow of the monarchy.

Afonso Celso, the President of the Council of Ministers who proposed the reforms in spite of Emperor Pedro II, who had no hopes of saving his system, not supporting them.

Among the reforms were the:

• Increase of provincial autonomy;

• Expansion of voting rights and electoral districts;

• Direct election of municipal administrators and provincial presidents and vice presidents;

• Reduction of the prerogatives of the Council of State;

• And the reduction of Senate terms from lifelong to eight-year ones.

Over the following months, the General Assembly also legalized civil marriage and birth and death certificates, estabilished new taxes, and allowed freedom of religion, although Catholicism remained official. However, the conservative landowners prevented the Liberal Party's new agricultural law from passing, and improvements to education and the creation of a civil code would only happen under the premiership of Rui Barbosa.

On the other hand, the reform package substantially reduced support for a republic, especially among landowners, with the coffee planters of the Paraíba Valley supporting the imperial government and estabilishing a mutually beneficial patronage relationship with it that lasted until Getúlio Vargas, from the Riograndense Republican Party, became Prime Minister.

Brazilian politics in the late 19th century

Between 1889 and 1899, the following Presidents of the Council of Ministers held the office:

39. Afonso Celso de Assis Figueiredo (Liberal, 1889–1891)

40. Prudente de Morais (Liberal, 1891–1893)

41. Rui Barbosa (Liberal, 1893–1895)

42. Campos Sales (Liberal, 1895–1897)

43. Rodrigues Alves (Liberal, 1897–1899)

All of those prime ministers (and all Brazilian ones for that matter, until Lauro Sodré in 1909) were from the Liberal Party, as the fading into obscurity of the Republican movement allowed the Luzias to estabilish themselves as the defenders of federalism and the Paulista oligarchy, with the Saquaremas (Conservative Party) realigning as the party of the declining North and centralized government.

Afonso Celso, Viscount of Ouro Preto, had sought to estabilish a large, private central bank akin to those in European countries in order to regulate finance. This plan was rejected by the Saquarema majority, as the Brazilian financial market was a "feud" of a few banking families.

Under the tenure of Rui Barbosa, several important reforms were done, such as the creation of a civil code and official separation of church and state. There wouldn't be any land reform until the 1930s, due to the influence the landed oligarchy had in the legislative branch.

On 15 January 1895, longtime Emperor Pedro II died at the age of 69, after 65 years of reign and 55 in power, being succeeded by his grandson Pedro de Alcântara, a 24 year-old and the first member of the House of Bragança to survive the "curse" that always killed the firstborn sons of the Portuguese and Brazilian royal families. Pedro III was a liberal, and cooperated with Parliament in passing reforms to reduce his power, but his primary interest was in facilitating credit for bankers, industrialists and planters.

Voter fraud continued unabated during the 1890s, and in 1894, a parliamentary comission was estabilished to search for a solution. It concluded an Electoral Court was needed to regulate elections, but it was only estabilished under the term of Lauro Sodré, an act historians attribute to his goal of restoring Saquarema dominance.

The Northeastern planters which had dominated Brazilian politics since colonization slowly faded into the background, with only gerrymandering and cronyism keeping this elite influent until it was swept away in the 1930s.

In 1901, the Moderating Branch, which allowed the Emperor to interfere in the other branches of government, was finally abolished, marking the moment the "new" oligarchies captured the state for good.

Brazilian politics and economy in the early 20th century

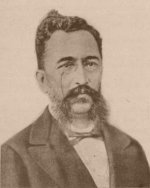

Rui Barbosa, an important Brazilian politician of the period.

Between 1901 and 1920, all ministerial cabinets other than Lauro Sodré (1909–1911), were dominated by the Luzias, who had leaders such as Rui Barbosa, Nilo Peçanha, Rodrigues Alves and Delfim Moreira. Barbosa served as Prime Minister between 1903 and 1905, 1911 and 1913, and 1915 and 1917. In 1919, the ease of credit led to a boom and bust cycle following WWI, and an economic depression which resulted in Conservative (Saquarema) dominance until the Great Depression.

Although the Liberals initially rigged elections in order to stay in power, and ensured government was dominated by the coffee planters from São Paulo and Minas Gerais, there was little corruption other than voter fraud, as Pedro III, like his father, had a list of politicians accused of corruption, who were never again allowed to hold public office; in spite of the Moderating Branch's abolition, the Emperor could still dissolve Parliament and schedule new elections, and the Luzia administrations oversaw the expansion of the railway network, wide access to credit for industrialists (outside of financial panics), greater investment in primary education, and the maintenance of low taxes. Also, the Electoral Court founded in 1909 by Sodré made fraud a thing of the past outside of the Sertão.

By 1920, railways crisscrossed virtually all of Southern Brazil, significantly easing transportation, although only the middle class could afford train tickets, and this amount of railroads led to environmental issues. Telegraph lines reached the remote Amazon Rainforest, especially with the short-liver rubber boom, and the ease of credit, coupled with foreign immigration, meant industrialisation progressed rapidly. Also by 1920, Brazil was considered to be a Great Power, participating in the Versailles Conference and becoming a founding member of the League of Nations.

In 1902, the Brazilian Socialist Party was founded in São Paulo, spreading to all Southern provinces by 1911; it was actually a coalition of regional parties whose strong showing in 1911, almost exclusively driven by the immigrant vote, led to Rui Barbosa passing a law authorizing the deportation of immigrants suspected of "subversive" activity, and the beginning of strike-breaking and union-busting activities by the Public Forces of various provinces.

In 1917, there was a general strike in São Paulo, which was Barbosa's cabinet sought a mediated solution for, only for the unions to refuse it; his cabinet soon broke the strike.

Afonso Celso, the President of the Council of Ministers who proposed the reforms in spite of Emperor Pedro II, who had no hopes of saving his system, not supporting them.

Among the reforms were the:

• Increase of provincial autonomy;

• Expansion of voting rights and electoral districts;

• Direct election of municipal administrators and provincial presidents and vice presidents;

• Reduction of the prerogatives of the Council of State;

• And the reduction of Senate terms from lifelong to eight-year ones.

Over the following months, the General Assembly also legalized civil marriage and birth and death certificates, estabilished new taxes, and allowed freedom of religion, although Catholicism remained official. However, the conservative landowners prevented the Liberal Party's new agricultural law from passing, and improvements to education and the creation of a civil code would only happen under the premiership of Rui Barbosa.

On the other hand, the reform package substantially reduced support for a republic, especially among landowners, with the coffee planters of the Paraíba Valley supporting the imperial government and estabilishing a mutually beneficial patronage relationship with it that lasted until Getúlio Vargas, from the Riograndense Republican Party, became Prime Minister.

Brazilian politics in the late 19th century

Between 1889 and 1899, the following Presidents of the Council of Ministers held the office:

39. Afonso Celso de Assis Figueiredo (Liberal, 1889–1891)

40. Prudente de Morais (Liberal, 1891–1893)

41. Rui Barbosa (Liberal, 1893–1895)

42. Campos Sales (Liberal, 1895–1897)

43. Rodrigues Alves (Liberal, 1897–1899)

All of those prime ministers (and all Brazilian ones for that matter, until Lauro Sodré in 1909) were from the Liberal Party, as the fading into obscurity of the Republican movement allowed the Luzias to estabilish themselves as the defenders of federalism and the Paulista oligarchy, with the Saquaremas (Conservative Party) realigning as the party of the declining North and centralized government.

Afonso Celso, Viscount of Ouro Preto, had sought to estabilish a large, private central bank akin to those in European countries in order to regulate finance. This plan was rejected by the Saquarema majority, as the Brazilian financial market was a "feud" of a few banking families.

Under the tenure of Rui Barbosa, several important reforms were done, such as the creation of a civil code and official separation of church and state. There wouldn't be any land reform until the 1930s, due to the influence the landed oligarchy had in the legislative branch.

On 15 January 1895, longtime Emperor Pedro II died at the age of 69, after 65 years of reign and 55 in power, being succeeded by his grandson Pedro de Alcântara, a 24 year-old and the first member of the House of Bragança to survive the "curse" that always killed the firstborn sons of the Portuguese and Brazilian royal families. Pedro III was a liberal, and cooperated with Parliament in passing reforms to reduce his power, but his primary interest was in facilitating credit for bankers, industrialists and planters.

Voter fraud continued unabated during the 1890s, and in 1894, a parliamentary comission was estabilished to search for a solution. It concluded an Electoral Court was needed to regulate elections, but it was only estabilished under the term of Lauro Sodré, an act historians attribute to his goal of restoring Saquarema dominance.

The Northeastern planters which had dominated Brazilian politics since colonization slowly faded into the background, with only gerrymandering and cronyism keeping this elite influent until it was swept away in the 1930s.

In 1901, the Moderating Branch, which allowed the Emperor to interfere in the other branches of government, was finally abolished, marking the moment the "new" oligarchies captured the state for good.

Brazilian politics and economy in the early 20th century

Rui Barbosa, an important Brazilian politician of the period.

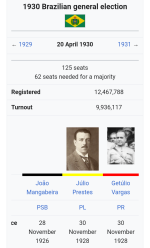

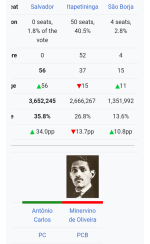

Between 1901 and 1920, all ministerial cabinets other than Lauro Sodré (1909–1911), were dominated by the Luzias, who had leaders such as Rui Barbosa, Nilo Peçanha, Rodrigues Alves and Delfim Moreira. Barbosa served as Prime Minister between 1903 and 1905, 1911 and 1913, and 1915 and 1917. In 1919, the ease of credit led to a boom and bust cycle following WWI, and an economic depression which resulted in Conservative (Saquarema) dominance until the Great Depression.

Although the Liberals initially rigged elections in order to stay in power, and ensured government was dominated by the coffee planters from São Paulo and Minas Gerais, there was little corruption other than voter fraud, as Pedro III, like his father, had a list of politicians accused of corruption, who were never again allowed to hold public office; in spite of the Moderating Branch's abolition, the Emperor could still dissolve Parliament and schedule new elections, and the Luzia administrations oversaw the expansion of the railway network, wide access to credit for industrialists (outside of financial panics), greater investment in primary education, and the maintenance of low taxes. Also, the Electoral Court founded in 1909 by Sodré made fraud a thing of the past outside of the Sertão.

By 1920, railways crisscrossed virtually all of Southern Brazil, significantly easing transportation, although only the middle class could afford train tickets, and this amount of railroads led to environmental issues. Telegraph lines reached the remote Amazon Rainforest, especially with the short-liver rubber boom, and the ease of credit, coupled with foreign immigration, meant industrialisation progressed rapidly. Also by 1920, Brazil was considered to be a Great Power, participating in the Versailles Conference and becoming a founding member of the League of Nations.

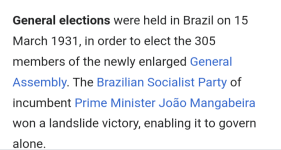

In 1902, the Brazilian Socialist Party was founded in São Paulo, spreading to all Southern provinces by 1911; it was actually a coalition of regional parties whose strong showing in 1911, almost exclusively driven by the immigrant vote, led to Rui Barbosa passing a law authorizing the deportation of immigrants suspected of "subversive" activity, and the beginning of strike-breaking and union-busting activities by the Public Forces of various provinces.

In 1917, there was a general strike in São Paulo, which was Barbosa's cabinet sought a mediated solution for, only for the unions to refuse it; his cabinet soon broke the strike.