The History of the United Kingdom of

Great Britain, Ireland and Hong Kong

==========================

The Locust Years (1938-1946)

British history after the Third Union can be summed up quite succinctly, as in

1889 and All That (the thrilling sequel to

1066 and All That) as “Napoleon and debris”. British history classes love to cover the many Napoleons and how they all affected British foreign policy, culminating in the Continental War.

Like any good movie, they end just as the final victory is gained. Everything that was sacrificed for that victory, the classes tend to cover fairly quickly, as if unwillingly and begrudgingly. But one cannot separate Britain of the 2020s from its past. The doors of the old House of Commons were broken not once, but twice. The first in glory and revolution in 1889, the second in destitution and ruin in 1931.

King George VI had a high task ahead of him, to declare victory in war while reassuring his people that the peace would be bright.

King George VI had a high task ahead of him, to declare victory in war while reassuring his people that the peace would be bright.

As the sun rose on a broken kingdom triumphant, the King wished to speak to his people. He was already known for his steely resolve, but his talent in public speaking was still green and untested. The speech would have to one of a victorious leader, but not too arrogant. He still could remember seeing the ruins of Parliament and having to flee Buckingham Palace. He still could remember receiving the news of his father dying. That was an unpleasant surprise, but even more unpleasant was when he was acclaimed King while at Balmoral. He believed that his elder brother could ride out the war. After all, he was young still, and could have had children.

But history was to end Edward IX and make George VI. The abrupt news combined with his stutter meant that the first speech was to put it charitable – average. It was through his actions that the public would be won over. Even though his father and brother perished, he refused to flee. It was his duty to lead his people through their darkest hour. And it was the darkest hour. The clouds always rang of the sound of bombs, France amplified the bombings as the tide of war turned against them.

The Tempest, as Britain called the on and off French bombings during the Great Continental War, took its toll on many British cities.

He knew his people suffered. He knew they still suffered. Many cities bombed to ruins. He even was appalled to hear that the Bristol Corporation went so far to declare that Bristolians would have to eat insects and other vermin to survive. To have a triumphant and joyful speech was right out. Triumphant yes. But humble. Consulting with the BBC writers and his own gut instinct, he worked out what would go down in history as the “Rex Populi” speech.

It started off matter-of-factly, announcing the end of the war and the acceptance of France’s surrender. Then the speech moved on to a quiet tribute to all soldiers of the Empire and its allies, “both those alive and those taken from us”. Finally, it spoke of the sacrifices made on the Home Front and how “in the time of unbridled war, everyone fought in their own way for this prized moment”, and concluded that “if our United Kingdom and its Empire lasts for thousands of years, men will still say that this war was where we steeled ourselves and fought every day as if it was our last. Truly they will say it was Britain’s finest hour.”

But finest hour or not, it still left gaping scars. Every city had rubbles, some even just were rubbles. The Ministry of All the Talents, the tripartisan coalition of the Tories, Liberals and Labour, refused to disband until the acute crisis was dealt with. First of all, food. The war forced the implementation of rationing, but even rationing had its limits when infrastructure were bombed. Herculean efforts to restore infrastructure and feed people, including feeding them relatively unfamiliar food that were easier to procure, were afoot. The Earl Woolton, pushed to his limits, would force the National Loaf and make the ‘Woolton pie’ a thing. But he would also acquire immense shipments of rice from Britain’s colonies (helmed by British men eager to feed the Old Country) that would be incorporated in many different meals for people to ensure they would get nutrition.

A 'meal box' would typically be made out of rice, meat (often beef or pork), vegetables and rarely (as seen here) boiled eggs.

A 'meal box' would typically be made out of rice, meat (often beef or pork), vegetables and rarely (as seen here) boiled eggs.

The “meal box”, a borrowing from Britain’s increasingly-distant Japanese ally, would find itself accepted in a society struggling to get enough nutrition. Rice, slices of beef, or other heavily-rationed meat, and vegetables like carrot, would be a regular worktime meal for many decades for British people. Rice (traditionally restricted to sweets such as rice pudding) came in its own with Britain at the most dire time in its cuisine, where rationing for years and years strangled many old traditions and the government was willing to try anything to feed its subjects.

In those years, the bald simple fact that Britain long outgrew its natural food output and was an importer country for centuries, was made painfully aware to its inhabitants. The rationing were insufficient even as rice and other foodstuff flowed in as the structure struggled to function with weak infrastructure and high demand, and many turned to the black market. Spivs thrived in the 1930s, and the end of war did not stop them. Everyone, from the Prime Minister to a lowly civilian, participated in illegal activity to acquire food to survive. “In those days, you either were a criminal, or you were dead.” Perhaps this led to the blasé attitude to low-level corruption we see today.

Not all crime was the black market for in the Locust Years, violent crime ran rampant. Most of them were your standard low-level thugs, seeking to profit from a country in crisis. A few were more structured and became gangs that terrorised urban areas as policing struggled. It became almost accepted that certain areas were the domain of certain gangs. Most of those would fade away, collapse to renewed police efforts, or go ‘legitimate’ by the 60s, but there were a few that had… an ideology, a greater purpose.

Thankfully for Britain, the Red Flag Brigade was merely one of a few ideological militias and not reflective of a wider trend.

Thankfully for Britain, the Red Flag Brigade was merely one of a few ideological militias and not reflective of a wider trend.

The Mosleyite Independent Labour Party (ILP) was loosely associated with Labour and also loosely associated with the ‘Red Flag Brigade’, a bunch of angry and deeply ideological primarily-young people who had read the Communist Manifesto and going off incomplete information about the regime east of Portugal, declared that in this clear crisis of imperialist capitalism, that they should rise up and take over the country and declare a restored Commonwealth on socialist principles. All grand ideas, but the execution was… lacking.

For you see, while young people were angry, they also were resigned, and many had a distrust of the weirdos with dog-eared red books shouting at them. In the end, the Brigade fled to the Pennine Mountains with stolen guns from the Home Guard after getting few people interested, and lasted a few years doing their quixotic ‘resistance’ before inevitably splitting and being cracked down by the Army. The connections to ILP and thus to Labour was a major embarrassment for Prime Minister Malcolm MacDonald who was forced to cease his party’s connection with the ILP to save face.

Never was Britain more in ‘splendid isolation’ than in the Locust Years. The Empire still ran like clockwork, the Prime Minister and King still signed off on foreign treaties especially when it came to finalising the long-sought-after peace, but the government was fundamentally disinterested in foreign affairs when Britain was still bombed. Ireland was for a time the more prosperous part of the Home Isles due to being bombed far less, and the Parliament of Ireland led by Lord Lieutenant William Norton (in one of the rare non-Tory governments) used this to squeeze concessions for Irish industries and interests, and his successor Joseph Martin continued such tactics upon his victory in the 1944 election.

The 1941 election was long overdue, with the last election being held in 1924. There were plenty of calls for the “Longest Parliament” to have an election before 1941, but the Ministry of All the Talents closed ranks and declared that the country was not ready for elections. At any other time, this would have been decried as dictatorial, but outside of Mosleyists and the hard-right nobody seriously opposed the sudden consensus between the country’s three major parties. The country won the war, but it was sickened in the process, and the 1938-1941 period needed to be a period of healing, or so that was the rhetoric. There were reshuffles to reorient focus on internal matters and the beefing up of the Ministries of Fuel and Power, Labour and National Service, National Insurance, and most significantly the position of First Commissioner of Works.

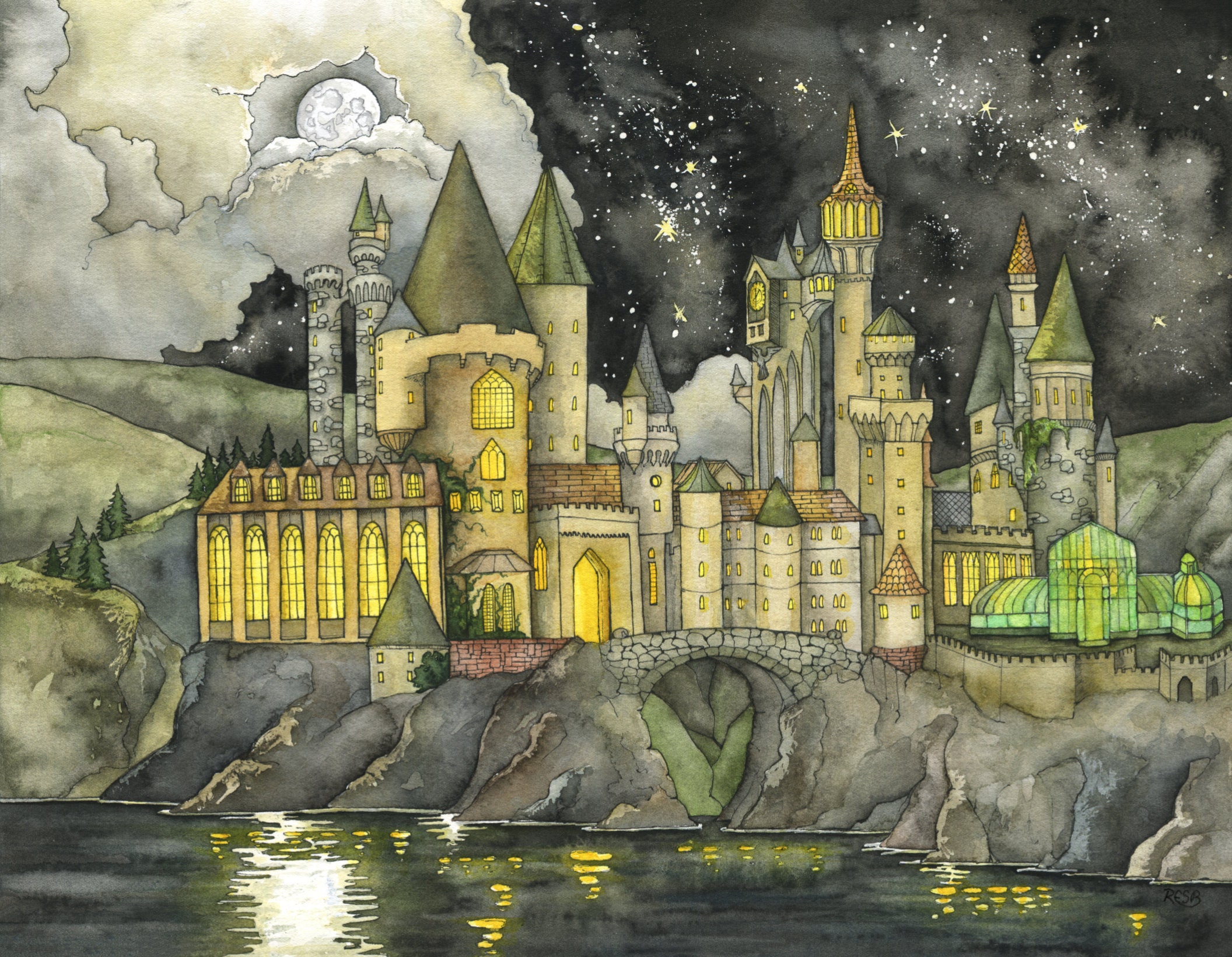

Even now, the De La Warr Pavilion in the District of East Sussex, along with others, pay tribute to the 'Man Who Rebuilt Britain'.

‘Buck’ De La Warr, the ninth Earl De La Warr, was First Commissioner of Works during the last Ministry of All the Talents (and later on the MacDonald government), and was by far the most powerful First Commissioner yet. Still in his thirties, and with a keen fascination for ‘decorativist’ architecture from his youth, he was given carte blanche to rebuild Britain as ‘a country that rises from the ruins’. At every turn, he prioritised building proposals that in his words, ‘will lead to the growth, prosperity and the greater culture of our nation’, hence modernist and decorativist.

Urban buildings, which he deemed to need the more ‘modern’ appearance, were far more emphasised on ‘decorativism’, and he implemented guidelines that would shape urban Britain’s look. Meanwhile as a country earl he wished for rural Britain to be rebuild in its own way to ‘capture the essence of deep England’, hence arts and crafts enjoyed a second wind in rural areas. This was a deeply quixotic approach in mixing two architecture styles, and more than once he was mocked at Cabinet for it, but his quick wit and charming personality ensured he could complete what he deemed his ‘project’, to make a new Britain from the ruins.

As a committed socialist (but far from the Mosleyists), he pushed hard for social housing, aka housing where the state owns it but people live there on the state’s agreement. This was something the Tories shied away from, preferring to commit to the late Noel Skelton’s ‘property-owning democracy’, and there was significant push-back. Cheap but purchasable housing was the watch-word up until 1941, then MacDonald permitted him to expand on his social housing policy as part of his grand plan to house as much Britons as possible. This would see the Tories push back eventually in reaction under Attlee and Salisbury, but the Earl got his way during 1941-1946, seeing the rapid growth of social housing as a thing in Britain. By the end of the Locust Years (commonly defined as the election of Clement Attlee), social housing was approaching 20% of all households, and despite the Conservatives’ efforts, this would only grow.

Thanks to the untiring efforts of the Earl De La Warr, the government of Prime Minister Malcolm MacDonald could champion that it all but ‘solved’ the housing crisis and rebuilt most of the cities in far less time than anticipated and in a very unique image that was then forever associated with the scarred defiance of post-war Britain and the declaration of a country in modernity, one transgressing old social boundaries to form something new. Before the Tempest, the South of England was widely seen as more prosperous than the North, with the South associated with leafy green and comfortable rural middle-class and the North a more working-class culture. The Tempest changed that, and many people moved north (some would say ‘fled’), and it was a keen emphasis of the Amery and MacDonald governments to build more houses in the South to get people to move back, and this was something Attlee would continue. The South would be shaped by this legacy, with many social housing in leafy grove and some craters if you know where to look.

As a consequence of all this, many of the old stratified class boundaries were shook up and people who came from ‘middle-class’ families and others from ‘working-class’ families would be thrown into the same mix, affected by the non-discriminative destruction of the Tempest and the movements of people north and then south again. The strong class stratification that defined the England that Karl Marx visited was if not obliterated than deeply blurred. The literati of this time period wrote of a ‘new society’ free from the idea of social class, but this new society was not seeping through to politics any time soon. The literati noted however, that eventually it would.

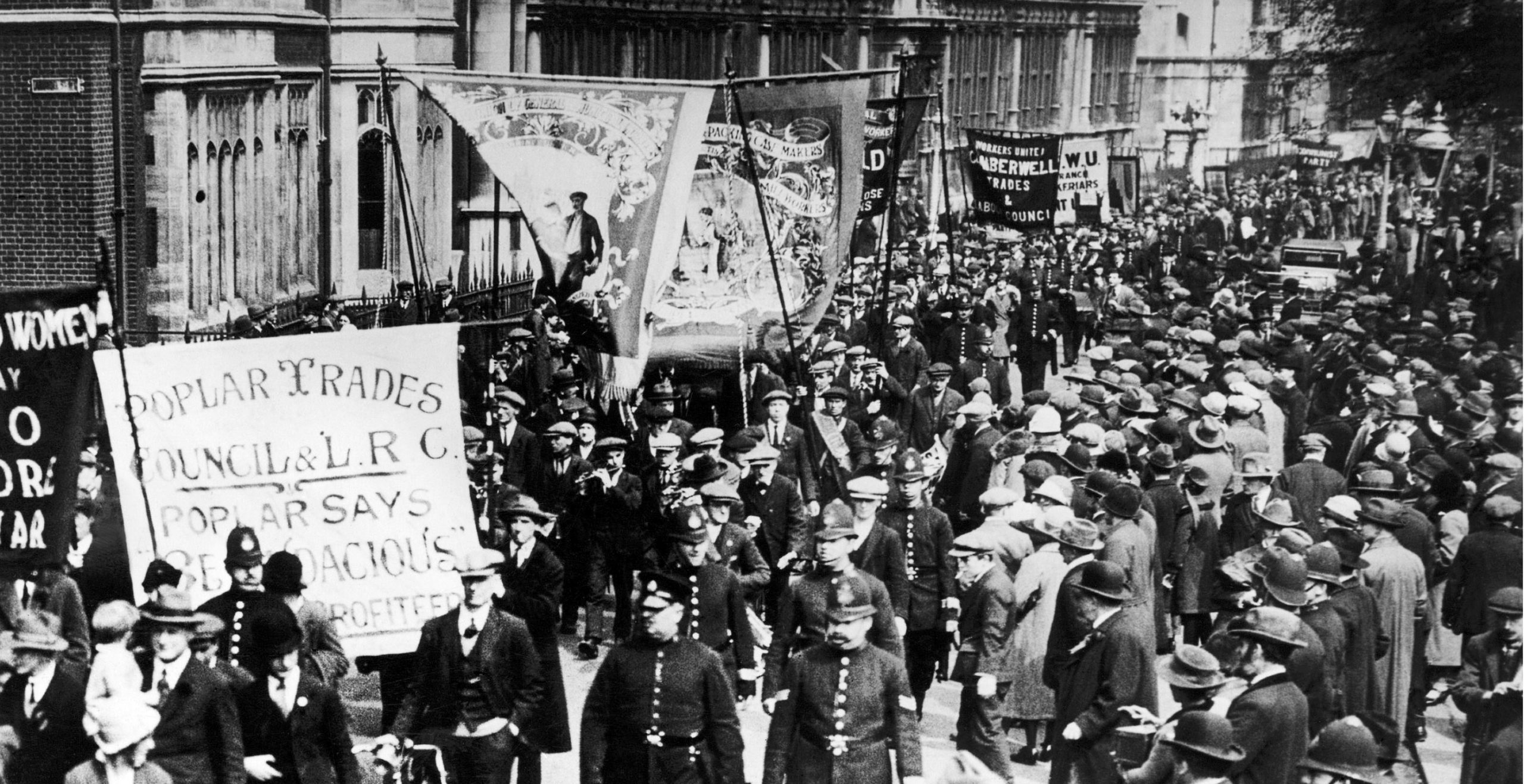

The 1945 general strike was in many ways the scream of a frustrated Britain, and by far its most impactful labour action.

The Red Flag Brigade was a humiliation to the Prime Minister, but a greater moment would come to the labour movement in 1945. Union membership was soaring, and union leaders were dissatisfied with the ‘moderate’ Labour leader who refused to go after the rich and even worked extensively with the Opposition. After much haggling and negotiation, and growing discontent over insufficient workers’ pay for a standard of living, the unions led by the TUC and their firebrand General Secretary James Maxton declared a general strike. The “Red Summer” it was called, and it was a great test of the reconstructed Britain’s so-called stability. The TUC issued a list of demands including better workers’ pay, but fatally overreached to including appointing union people to the House of Lords.

The workers that struck were less than expected despite the unpleasantly low wages, Maxton knew this, but he persisted. Eventually things would budge and the government would give in. But MacDonald stood up with a steely face in the Commons, and declared that while he was a socialist, he would never give in to “a reign of terror by radical councilists of the likes of Americans and Spaniards”. Standing firm, he declared that Britain have had enough of people who seek to divide the country, and pledged to implement a satisfactory minimum wage if the strike ended. In a sense, this was conceding the original demand without ceding power or ground to Maxton and the ‘councilist threat’. This was aired nation-wide, and was a major blow to the “Red Summer”.

Maxton however, refused to budge, and under great pressure the greater TUC organisation buckled, removing Maxton and replacing him with the more ‘constructive’ Walter Citrine. This major defeat for the labour movement at such an inopportune time led to people increasing moving from the ‘big’ unions to small unions, or to the cooperatives which saw a major boom in the aftermath. MacDonald however, would see the Party mutter about him going against the unions, and Mosley would make hay out of him betraying the workers. In the end, the event defined Malcolm MacDonald and took him from helming an incoherent and weak government with success primarily off great negotiations with the Liberals and Conservatives, to a good Prime Minister. However, the Party was starting to fall apart as a result of this as left and right tore each other apart, and the 1946 election was a foregone conclusion.

Still, the Houses of Parliament were close to completion (done up in the old arts and crafts style over the Earl’s private objections), people were reasonably housed and fed, cities were rebuilt (unrecognisably so) and the Downing Street Complex was finished a month before the election. In the end, the locusts died after eight years of turmoil, and after a handshake with the old Prime Minister and a visit to the King in the rebuilt Buckingham Palace, the new Prime Minister was ready to make changes of his own. The time of Clement Attlee was here.