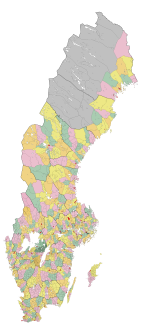

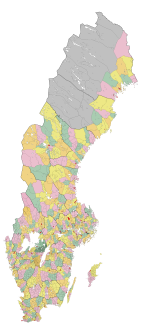

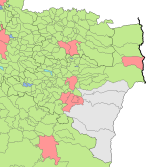

So here's something unrelated to the previous (take a shot, everyone): I've taken my very best shot at bringing the big basemap of Swedish parishes back to 1863, the year the Municipal Ordinances came into effect and civil and ecclesiastical administration was separated. These laws applied throughout the country except in Lapland, where the sparse and "uncivilised" nature of the local population meant it took another eleven years before the reform was implemented.

The Ordinances created 2,358 rural municipalities, most of which were derived from one whole Church of Sweden parish, although there were a few exceptions where small parishes (mainly in Västergötland and Östergötland) were merged to make administration more efficient. Even then, most municipalities were very small, counting only a few hundred residents - this wasn't that big of a deal, since local municipalities had limited powers in rural areas and mainly administered poor relief. There was no planning outside of towns at this point, roads were maintained by local landowners, and schools continued to be run by the Church until 1930. To handle issues too wide-ranging or costly for the local municipalities, mainly agricultural aid and public health (and later on also hospitals), a related ordinance set up county councils (

landsting) which were elected by the same census franchise as the local municipalities, had a number of councillors that were in fixed proportions to population (one per 5,000 urban residents and 7,000 rural residents, at least later on), and would additionally serve as electors for the First Chamber of the Riksdag when that was created in 1866.

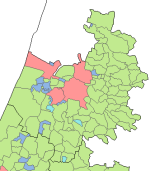

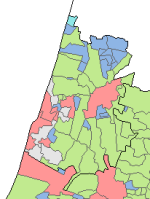

There were also a large number of very illogical and impractical boundaries still in place at this point, some of which were exclaves (mainly in Dalarna and other sparsely-settled areas), but most of which were to do with parishes being split between multiple hundreds, and in some cases, multiple counties. The south of Sweden was particularly notorious for this, with boundary-crossing parishes practically being the norm in both Scania and Småland. Småland even has a dialect word (

skate - that's pronounced with two syllables) meaning "a part of a parish that's separated from it by a higher administrative boundary". One of these - the

Skårdals skate area directly across the river from Kungälv, just north of Gothenburg - had even been in a separate

country from the main part of the parish until 1658, when Bohuslän belonged to Norway. Residents of the area were said to be "Norwegian in body and Swedish in soul", since they paid taxes to the Norwegian crown but went to church across the border in Sweden.

What about urban areas, then? Well, the 88 towns in Sweden had already had some form of self-rule, but the Ordinances standardised the form of governance across the entire country and removed the role of guilds and other social corporations in electing town councils. Along with the 1864 law establishing freedom of enterprise throughout the country, this ended the privileged role of the towns in the economy, but they continued to be distinguished from rural areas in law. Broadly speaking, we can say towns were more powerful than rural municipalities, but also less autonomous. On the one hand, they had authority over things like planning, public health and fire safety, but on the other hand, the city council's power over these matters was tempered by the presence of the magistrates, who were judges appointed by the central government and, in addition to running the local judiciary, had effective veto power over the council's decisions.

In addition to towns and rural municipalities, there was also a secret third thing -

köpingar, which were marketplaces (under the old trade laws predating the freedom of enterprise) that didn't have full town status. Most of these were

lydköpingar, which were ruled by a town in the local area, but there was also a small number of

friköpingar which had their own councils but lacked several of the powers given to towns. Seven of these - two

lydköpingar (Ronneby, which had sorted under Karlskrona, and Mönsterås, which had sorted under Kalmar) and five

friköpingar (Arvika, Lysekil, Malmköping, Motala and Örnsköldsvik) were given autonomy by the Ordinances and allowed to form councils with essentially the same powers as rural municipalities - in later years, they would gain power over planning and fire safety, and the right to voluntarily implement the other powers of towns, but they remained under rural jurisdiction throughout their existence. Over the years, a great many more

köpingar would be established, usually in industrial settlements that weren't thought big enough for full town status, and in many cases leading on to the granting of town status later on.