The first election held on the set of boundaries that would last thirty years was also one of the most dramatic in Indian history. The Indian National Congress, which had ruled the country without much opposition since independence, had lost much favour over the previous six years, largely due to the increasingly heavy hand of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her closest associates in running both the party and the country. Indira had come to power in 1966, two years after the death of her father, India's first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Like her father, she believed in developing India in a socialist direction, relying on the country's natural wealth and partners in the Soviet Union and other formerly-colonised nations to forge a path separate from European influence. Her rise to power saw a populist turn in the ruling party, with policies including the nationalisation of the banking sector and the abolition of the privy purse (the system of annual payments to former rulers of princely states) being announced and implemented at breakneck speed with little public consultation. This brought her into conflict with a number of regional Congress leaders, who successfully persuaded the party bureaucracy to have Indira expelled in November 1969. Indira was not cowed by this, obviously, and the result was a split in the party, with Indira leading the Congress (R) and her opponents the Congress (O). Both parties entered the 1971 general election, but even though the Congress (O) and its allies stood candidates in every seat, Indira's Congress (R) trounced them everywhere except in Gujarat, where a number of Congress (O) leaders had their base.

Having gotten a clear mandate for her policies independent of the Congress organisation and name loyalty, Indira set about reshaping the country in her image. Part of this, to her credit, was delivering on the 1971 campaign slogan

Garibi hatao, desh bachao ("remove poverty, save the country") - the 5th Five-Year Plan, beginning in 1974, included a number of policies designed to alleviate rural poverty and develop the country's education and utility infrastructure. Unfortunately, the 1973 oil crisis affected India just as it did the rest of the world, and the goal of

garibi hatao was very quickly put on the back burner. Instead, Indira's government came to focus more and more on suppressing internal dissent, which was beginning to flourish owing to many of the same issues that had precipitated the Congress split in 1969. Put simply, Indira and her inner circle had gotten a reputation for disregarding democracy, which stemmed in part from them pushing through their preferred reforms without discussion or reflection, but also in part from the actual erosion of key democratic institutions under their rule. Back in 1967, the Supreme Court had ruled that those parts of the Constitution that dealt with fundamental civil rights could not be amended unilaterally by Parliament, and Indira's response was to pass a new amendment saying "yes we can" and promote a relatively junior Supreme Court justice, A.N. Ray, to the position of Chief Justice on the basis that he'd written the dissent in the original case. Ray's appointment was widely seen as a move to seize control of the judiciary, and raised such a furore among the legal profession that the Indian bar actually went on strike in 1976.

But it wasn't all questions of high democratic principle - Indira herself also came under attack at this point. After the 1971 election, the Prime Minister's main opponent in her own constituency of Rae Bareli, a Samyukta Socialist Party candidate and former independence activist named Raj Narain, sued her in court for electoral malpractice, arguing that the Congress (R) had bribed voters and used government employees as campaign workers. The case was tried at the Allahabad High Court, which in June 1975 ruled that Narain's charges were accurate and found Indira guilty of electoral malpractice, ordering her to resign from office within twenty days and barring her from standing for election for a period of six years. Indira appealed the ruling to the Supreme Court, and two weeks afterward, President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed declared a nationwide state of emergency on her advice.

The Emergency, as it's become known, lasted for 21 months, and saw an enormous crackdown on politics and civil society, with tens of thousands of people arrested under national security legislation passed in the years before, many of them key opposition leaders. Many of these were tortured or otherwise mistreated in jail, and in general the police and security services, by now thoroughly loyal to the Congress (R) government, were let loose in the cities and towns. A key figure in this was Sanjay Gandhi, Indira's younger son, who was one of his mother's most important advisers despite holding no political office, and who would become one of the most powerful men in the country during the Emergency. Sanjay had very few qualms about respecting democratic norms, conferring only with a few trusted friends and using his untouchable status as the Prime Minister's son to impose his will on the country, and the city of Delhi in particular. In April 1976, when visiting the old town of Delhi, he complained to a city official that there were tenements blocking his view of the Jama Masjid, and the Delhi Development Authority proceeded to have the tenements demolished, displacing 70,000 residents with very little notice and killing some 150 of them when they protested and the police opened fire. In September, Sanjay led the implementation of a new "family planning" scheme, allegedly designed to address the IMF's concerns about overpopulation in India, whose centrepiece was a programme of sterilisation of lower-class (and lower-caste) people. On paper, the programme was always voluntary, with participants receiving either a straightforward cash payment or a housing loan on favourable terms from one of the nationalised banks in exchange for undergoing sterilisation. However, local governments were very eager to meet quotas, and reports of people being herded into camps and forcibly sterilised are so common that it's hard to argue there wasn't a systemic campaign of compulsory sterilisation going on. The sterilisation campaign is maybe the single most infamous aspect of the Emergency, and family planning remains a toxic subject in Indian politics to this day.

Despite the arrests, the press censorship and what few social programmes still remained despite the shift in priorities, opposition to the Congress (R) government (rebranded as Congress (I) during the Emergency, with I naturally standing for Indira) was growing by the day. As early as July 1975, Sikh leaders in Punjab had organised the

Democracy Bachao Morcha (Save Democracy Front), which called for mass protests to oppose the "fascist tendencies" of the Congress, and which led to over 40,000 Sikhs getting arrested over the following two years, more than a third of all arrests made during the Emergency. This massive Sikh resistance didn't come out of nowhere - the group had been engaged in disputes against the central government ever since independence, for many different and complex reasons, but the long and short of it was that Sikhs, and Punjabis generally, had felt disadvantaged by the central government's actions for a long time before the Emergency and now saw their last chance to resist or watch India turn into a police state. This sentiment was echoed by many other groups in India, particularly in North India, whose river plains were and are the poorest and most densely-populated regions of the country, thus making them the epicentre of the sterilisation campaigns. Jayaprakash Narayan (popularly known as JP), a Marxist and former independence activist from the Bhojpuri region of Bihar, had led a mass movement against the state government of Bihar during previous years. When the Emergency was declared, JP's calls for a

Sampurna Kranti (Total Revolution) against Congress excesses and social injustice attracted hundreds of thousands of people to his protest rallies and millions to his movement before he was jailed. He would be released in November 1975 to get treatment for kidney failure, and spent the rest of his life in very poor health, but by that point he was a nationally recognised symbol of democracy.

Far from uniting India behind her, Indira's heavy-handed policies had actually succeeded, if only for a short while, in uniting almost the whole political scene in opposition to her continued rule. Both the communist movement, which had been growing in states like Kerala and West Bengal thanks to massive rural poverty and anti-Vietnam War sentiment, and the Hindu nationalist milieu around the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh were targeted as potential cores of resistance, and both groups eventually agreed to join forces against Indira alongside the Congress (O) and related groups. This alliance was extremely heterogeneous, and for lack of a better unifying factor, the dissident Congress elements found themselves leading it due to their relatively centrist outlook. The RSS would never have accepted a leftist leader, the CPI(M) would never have accepted a Hindu nationalist one, but in the figure of Morarji Desai, former Finance Minister and Congress (O) stalwart, they found an acceptable compromise. Desai had reasonably good opposition credentials, having gone on hunger strike and been jailed due to his support for the

Navnirman Andolan (Reconstruction Movement) protests in his home state of Gujarat, but he was also past his eightieth birthday and unlikely to rock the boat too much in either direction.

In January 1977, having extended the Emergency twice, Indira decided to lift some of the restrictions and give the people the chance to give her another mandate at the ballot box. She had little reason to suspect this wouldn't work - after all, everyone around her was telling her how popular she was, the press (censored by government order) was giving nothing but praise for her leadership and her government's programmes, and everyone who'd predicted her downfall in the 1971 election had been spectacularly wrong. But of course, 1977 was not 1971. As mentioned, India had been wracked by constant protests and resistance movements even before the Emergency was declared, and the appearance of armed troops in the towns and sterilisation camps in the villages had done nothing to make the government more popular. From the moment elections were called, the opposition alliance mobilised their forces - two days later, the

Janata Party was formed as a unified organisation for all but the leftist and regionalist elements of the coalition. The core of the JP was the Congress (O), the centre-left Samyukta Socialist Party, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Jana Sangh, and the Bharatiya Lok Dal, which was itself a merger of several anti-government factions including the liberal Swatantra Party and the Congress Socialist Party. The BLD would lend its electoral registration to the JP, since there wasn't time to register the alliance as a new political party, and it quickly hammered out a seat-sharing agreement with the Left Front in West Bengal, the Shiromani Akali Dal in Punjab, the Peasants' and Workers' Party in Maharashtra and the independent Congress (O) remnant as well as the DMK in Tamil Nadu.

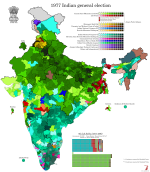

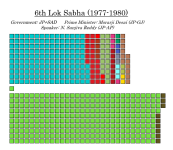

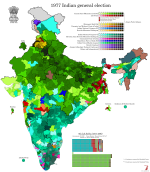

Congress (I), meanwhile, spent the entire campaign getting increasingly rattled, with several cabinet ministers crossing the floor to the opposition and Indira offering very little except vague promises of future economic development, which rang more hollow than ever. From the very beginning, momentum was with the opposition, and when the people went to the polls in March, Congress was handed its worst defeat to date. The government did relatively well in the south and the northeast, holding majorities of seats in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Assam, and was relatively competitive in Maharashtra and Gujarat. In the north, however, they were utterly, utterly routed, with not a single seat in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana or Punjab staying with them, and only a couple of seats in West Bengal and one each in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. Indira herself lost Rae Bareli to Narain, who stood again as the JP candidate and won convincingly (although it was still the weakest opposition majority in UP). The sweep in West Bengal can be attributed in large part to the Left Front, which would take power on the state level in June, inaugurating India's longest-serving communist state government.

Morarji Desai was sworn in as Prime Minister by Acting President B.D. Jatti on 24 March, four days after the end of polling. Aside from Akali Dal leader Parkash Singh Badal, who took office as Minister of Agriculture, the cabinet included only JP members - the other allied parties all went into opposition. Even so, and despite their stable majority in the Lok Sabha, the Desai ministry would only last a little over two years before internal divisions caused it to collapse.