India 1980

- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

The first attempt to unite anti-Congress forces into a working government was a dismal failure. The Janata Party had performed well in the 1977 elections, sure, but their only unifying factor was the sense of urgency in preventing Indira Gandhi and her government from retaining power after the Emergency. Once Morarji Desai had come to power and completed the reversal of the Emergency, there were a thousand different voices within his own coalition on how to proceed, and ultimately, none of them would fully emerge triumphant.

Desai's first act in power was to release all those prisoners remaining in Indian jails whose charges were considered political, and to introduce constitutional amendments to strengthen human rights protections and prevent the abuses of power that characterised the Emergency from happening again. To further drive this point home, investigations were launched into leading government figures of the previous parliamentary term, including Indira and Sanjay Gandhi. Sanjay was investigated primarily for his role in running state-owned carmaker Maruti Motors Ltd., which had been started in 1971 with the goal of producing an Indian-made car that would be affordable to India's growing lower middle classes. Maruti had still never produced a single car by this time, but Sanjay Gandhi had made millions off his position as managing director and, given that Maruti had been given an exclusive licence to produce its proposed class of car, he could be expected to make even more if production ever started.

Indira had been offered a comfortable exile by the King of Nepal, but after some consideration declined this and decided to stay in India and fight back. In October 1978, the Lok Sabha seat of Chikmagalur in Karnataka was vacated by its sitting member, D. B. Chandregowda, explicitly to allow Indira to return to parliament. The Janata Party made an attempt to recruit Kannada cinema legend Dr. Rajkumar as their candidate against her, but he declined citing a desire to stay apolitical, and the by-election was a slam dunk for Congress. Shortly afterward, however, Union Home Minister Charan Singh issued warrants for Indira and Sanjay's arrests, charging them with corruption and abuse of power so vague that they would be almost impossible to prove in court - among other things, they alleged that Indira had plotted to have jailed opposition leaders killed. Far from immobilising Congress, the arrests were a huge tactical error, and made it look as though the Janata Party was out for revenge rather than justice. Matters were not helped on 20 December, when two Congress supporters hijacked an Indian Airlines plane between Calcutta and Lucknow demanding Indira's immediate release. This was not granted, but the hijacking ensured that Indira was already a martyr before her trial even began.

By that time, the Janata Party was already splitting down the middle. As mentioned, the party had very little to unite it other than prosecuting Indira and the other key figures in the Emergency, and while Morarji Desai was able to achieve a few things as Prime Minister - notably normalising relations with China and Pakistan (though not to the point of settling border disputes with either country) and appointing the Mandal Commission to identify and propose policies to improve the lot of India's "socially or educationally backward classes" - there was no agreement within the government on how to deal with India's still-ongoing economic crisis. In late 1977, the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act was passed, imposing strict controls on currency exchange and effectively requiring multinationals seeking to do business in India to partner with domestic Indian companies. Economic nationalism was one of few principles shared by socialists, populists and Hindu nationalists, but the FERA failed to achieve its goals in multiple different ways: it did very little to stave off the multinational presence in India's economy in the long run, but in the short run, it caused a large exodus of cash and resources as American conglomerates scrambled to leave the Indian market before the new regulations went into effect. Most famously, Coca-Cola pulled out of India altogether, and for a brief time, the Indian state entered the soda market with a drink labelled "Double Seven" - believed by some to be a reference to the 1977 defeat of Congress, and making the drink immediately controversial.

Beyond selling soft drinks, it's hard to say the Desai ministry had any economic policy whatsoever. If anything, the two sides of the Janata Party - the secular socialists led by George Fernandes and Charan Singh on the one hand, and the Hindu nationalists led by L.K. Advani and Atal Bihari Vajpayee on the other - were more interested in preventing the other from achieving their goals than they were in advancing their own ones. The issue came to a head in summer 1979, when left-leaning members of the cabinet floated the idea that the Janata Party should ban its members from being part of any "alternative social or political organisation", a fairly direct reference to the RSS, which still counted most of the Hindu nationalist faction including Advani and Vajpayee as members. When Desai, fearing for his majority, refused to go along with this, Charan Singh and several dozen of his followers, including Fernandes as well as Indira's old foe Raj Narain, resigned both from cabinet and from the party, depriving the Janata Party of its parliamentary majority. Charan Singh, despite having been the driving force behind the arrests of Indira and Sanjay less than a year before, reached out to Congress and tried to make a deal whereby his faction of the Janata Party, now styling itself the Janata Party (Secular), would be permitted to govern with Congress support. Indira tentatively agreed on the condition that the charges against her and Sanjay be dropped, but Charan Singh refused to go along with this and was promptly denied confidence by the Lok Sabha. He resigned as Prime Minister after less than a month in office, and arranged to have the Lok Sabha dissolved pending elections in January 1980.

There were now two different Janata Parties heading into the election, and two Congresses as well - when Indira announced that Sanjay would be standing for election as the Congress candidate in Amethi, the seat bordering Rae Bareli, regional Congress leaders who hadn't been part of the inner circle during the Emergency balked. Karnataka chief minister D. Devaraj Urs went so far as to break off from the party and found his own, which became known as Congress (Urs) or Congress (U) and attracted support in a number of different states. However, Congress (U) never really became a mass party, and only attracted support in the constituencies of its own leaders. On the whole, the "official" Congress - Congress (I) - was once again the only nationwide force in India, and just about everyone predicted a landslide victory in spite of the still-fresh wounds of the Emergency.

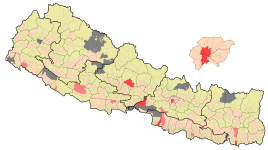

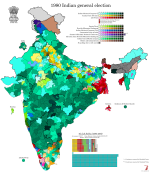

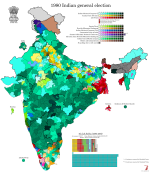

They were right, too. Congress took 353 seats in the new Lok Sabha, a stronger majority than the Janata Party before it, and no other party reached the 55 seats needed to form an official opposition. Although the "official" Janata Party, which was supported by the RSS and its large ground organisation, placed a fairly solid second in the popular vote, both the Janata Party (Secular) and the CPI(M) won more seats than it. Taken alongside their Left Front allies and the tentatively-allied CPI, the communist bloc was the second-largest in the chamber, and candidates endorsed by the Left Front won all but four seats in West Bengal in particular, a sign of the popular groundswell backing Jyoti Basu's state government and its land-reform agenda. The JP(S), meanwhile, achieved great strength in the countryside around Delhi, as well as parts of eastern UP and Bihar, but failed to really break through anywhere else. The opposition to Indira was much more fractured than Congress had been in the previous term, and for all intents and purposes, she now had the run of the country once again.

EDIT: Oh, and the bulk of Assam didn't vote in this election or the next one, due to a massive nativist campaign organised by the All Assam Students Union to prevent the granting of civil rights (including the right to vote) to Bangladeshi refugees living in the state, to the point where adherents attacked polling booths to disrupt any election where Bengalis might be on the electoral rolls. The situation wasn't resolved until 1985, when the central government essentially caved to the nativist movement's demands, and tensions between native Assamese and Bengali migrants continue to simmer to this day.

Desai's first act in power was to release all those prisoners remaining in Indian jails whose charges were considered political, and to introduce constitutional amendments to strengthen human rights protections and prevent the abuses of power that characterised the Emergency from happening again. To further drive this point home, investigations were launched into leading government figures of the previous parliamentary term, including Indira and Sanjay Gandhi. Sanjay was investigated primarily for his role in running state-owned carmaker Maruti Motors Ltd., which had been started in 1971 with the goal of producing an Indian-made car that would be affordable to India's growing lower middle classes. Maruti had still never produced a single car by this time, but Sanjay Gandhi had made millions off his position as managing director and, given that Maruti had been given an exclusive licence to produce its proposed class of car, he could be expected to make even more if production ever started.

Indira had been offered a comfortable exile by the King of Nepal, but after some consideration declined this and decided to stay in India and fight back. In October 1978, the Lok Sabha seat of Chikmagalur in Karnataka was vacated by its sitting member, D. B. Chandregowda, explicitly to allow Indira to return to parliament. The Janata Party made an attempt to recruit Kannada cinema legend Dr. Rajkumar as their candidate against her, but he declined citing a desire to stay apolitical, and the by-election was a slam dunk for Congress. Shortly afterward, however, Union Home Minister Charan Singh issued warrants for Indira and Sanjay's arrests, charging them with corruption and abuse of power so vague that they would be almost impossible to prove in court - among other things, they alleged that Indira had plotted to have jailed opposition leaders killed. Far from immobilising Congress, the arrests were a huge tactical error, and made it look as though the Janata Party was out for revenge rather than justice. Matters were not helped on 20 December, when two Congress supporters hijacked an Indian Airlines plane between Calcutta and Lucknow demanding Indira's immediate release. This was not granted, but the hijacking ensured that Indira was already a martyr before her trial even began.

By that time, the Janata Party was already splitting down the middle. As mentioned, the party had very little to unite it other than prosecuting Indira and the other key figures in the Emergency, and while Morarji Desai was able to achieve a few things as Prime Minister - notably normalising relations with China and Pakistan (though not to the point of settling border disputes with either country) and appointing the Mandal Commission to identify and propose policies to improve the lot of India's "socially or educationally backward classes" - there was no agreement within the government on how to deal with India's still-ongoing economic crisis. In late 1977, the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act was passed, imposing strict controls on currency exchange and effectively requiring multinationals seeking to do business in India to partner with domestic Indian companies. Economic nationalism was one of few principles shared by socialists, populists and Hindu nationalists, but the FERA failed to achieve its goals in multiple different ways: it did very little to stave off the multinational presence in India's economy in the long run, but in the short run, it caused a large exodus of cash and resources as American conglomerates scrambled to leave the Indian market before the new regulations went into effect. Most famously, Coca-Cola pulled out of India altogether, and for a brief time, the Indian state entered the soda market with a drink labelled "Double Seven" - believed by some to be a reference to the 1977 defeat of Congress, and making the drink immediately controversial.

Beyond selling soft drinks, it's hard to say the Desai ministry had any economic policy whatsoever. If anything, the two sides of the Janata Party - the secular socialists led by George Fernandes and Charan Singh on the one hand, and the Hindu nationalists led by L.K. Advani and Atal Bihari Vajpayee on the other - were more interested in preventing the other from achieving their goals than they were in advancing their own ones. The issue came to a head in summer 1979, when left-leaning members of the cabinet floated the idea that the Janata Party should ban its members from being part of any "alternative social or political organisation", a fairly direct reference to the RSS, which still counted most of the Hindu nationalist faction including Advani and Vajpayee as members. When Desai, fearing for his majority, refused to go along with this, Charan Singh and several dozen of his followers, including Fernandes as well as Indira's old foe Raj Narain, resigned both from cabinet and from the party, depriving the Janata Party of its parliamentary majority. Charan Singh, despite having been the driving force behind the arrests of Indira and Sanjay less than a year before, reached out to Congress and tried to make a deal whereby his faction of the Janata Party, now styling itself the Janata Party (Secular), would be permitted to govern with Congress support. Indira tentatively agreed on the condition that the charges against her and Sanjay be dropped, but Charan Singh refused to go along with this and was promptly denied confidence by the Lok Sabha. He resigned as Prime Minister after less than a month in office, and arranged to have the Lok Sabha dissolved pending elections in January 1980.

There were now two different Janata Parties heading into the election, and two Congresses as well - when Indira announced that Sanjay would be standing for election as the Congress candidate in Amethi, the seat bordering Rae Bareli, regional Congress leaders who hadn't been part of the inner circle during the Emergency balked. Karnataka chief minister D. Devaraj Urs went so far as to break off from the party and found his own, which became known as Congress (Urs) or Congress (U) and attracted support in a number of different states. However, Congress (U) never really became a mass party, and only attracted support in the constituencies of its own leaders. On the whole, the "official" Congress - Congress (I) - was once again the only nationwide force in India, and just about everyone predicted a landslide victory in spite of the still-fresh wounds of the Emergency.

They were right, too. Congress took 353 seats in the new Lok Sabha, a stronger majority than the Janata Party before it, and no other party reached the 55 seats needed to form an official opposition. Although the "official" Janata Party, which was supported by the RSS and its large ground organisation, placed a fairly solid second in the popular vote, both the Janata Party (Secular) and the CPI(M) won more seats than it. Taken alongside their Left Front allies and the tentatively-allied CPI, the communist bloc was the second-largest in the chamber, and candidates endorsed by the Left Front won all but four seats in West Bengal in particular, a sign of the popular groundswell backing Jyoti Basu's state government and its land-reform agenda. The JP(S), meanwhile, achieved great strength in the countryside around Delhi, as well as parts of eastern UP and Bihar, but failed to really break through anywhere else. The opposition to Indira was much more fractured than Congress had been in the previous term, and for all intents and purposes, she now had the run of the country once again.

EDIT: Oh, and the bulk of Assam didn't vote in this election or the next one, due to a massive nativist campaign organised by the All Assam Students Union to prevent the granting of civil rights (including the right to vote) to Bangladeshi refugees living in the state, to the point where adherents attacked polling booths to disrupt any election where Bengalis might be on the electoral rolls. The situation wasn't resolved until 1985, when the central government essentially caved to the nativist movement's demands, and tensions between native Assamese and Bengali migrants continue to simmer to this day.

Last edited: