As if the schizophrenic nature of this thread over the past week or two wasn't proof enough that I'm spiralling mentally, I've actually started attempting to map the Frankfurt National Assembly elections.

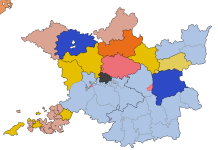

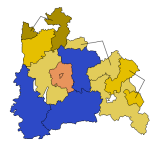

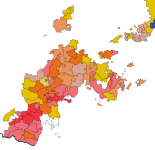

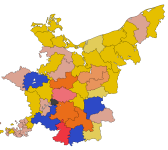

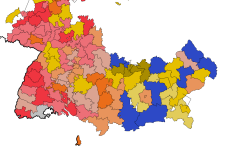

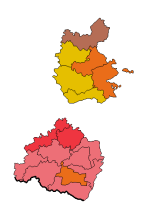

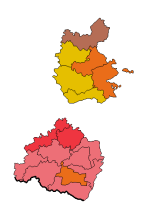

Red is the Donnersberg faction, which was the most radical and wanted a democratic republic modelled on the United States. They originated as a split from the Deutscher Hof faction, in pale red, who were also committed to universal suffrage and the creation of a new German state with none of the trappings of the old order, but were generally less keen on revolutionary violence as a way to get there. The Westendhall faction, in orange, was a rightward split from the Deutscher Hof, and were nicknamed "the left in white tie" by their more radical colleagues - they nominally also supported a republic, but voted with the assembly's monarchists a number of times and were generally somewhat agnostic on the issue as long as some sort of liberal democratic order was established. This brought them pretty close to the Casino faction, in yellow, who were moderate liberal constitutionalists, most of whom supported a property-based franchise and a constitutional monarchy. The Casino were the biggest faction overall in the Assembly, although around a third of the membership belonged to no faction - the only such member seen here was the member for Nassau 1, which is depicted in independent brown as a result.

Red is the Donnersberg faction, which was the most radical and wanted a democratic republic modelled on the United States. They originated as a split from the Deutscher Hof faction, in pale red, who were also committed to universal suffrage and the creation of a new German state with none of the trappings of the old order, but were generally less keen on revolutionary violence as a way to get there. The Westendhall faction, in orange, was a rightward split from the Deutscher Hof, and were nicknamed "the left in white tie" by their more radical colleagues - they nominally also supported a republic, but voted with the assembly's monarchists a number of times and were generally somewhat agnostic on the issue as long as some sort of liberal democratic order was established. This brought them pretty close to the Casino faction, in yellow, who were moderate liberal constitutionalists, most of whom supported a property-based franchise and a constitutional monarchy. The Casino were the biggest faction overall in the Assembly, although around a third of the membership belonged to no faction - the only such member seen here was the member for Nassau 1, which is depicted in independent brown as a result.