Presidents of the United States

1801-1809: Thomas Jefferson (Republican)

1800: (with Aaron Burr) def. John Adams/Charles C. Pinckney (Federalist)

1804: (with George Clinton) def. Charles C. Pinckney/Rufus King (Federalist)

Winning the 1800 election on a repudiation of the Federalists, the Quasi War, and its associated abuses, and after fighting off an attempt by his running mate to take the presidency, Jefferson got to work on establishing the Republican vision of society. He ended the Quasi War and repealed the Alien and Sedition Acts, and he focused on establishing an agrarian economy. Policies of free trade depressed manufacturing, and the end of the French Revolutionary Wars opened up vast markets for American grain. And his Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin got to work on ending the public debt, though he convinced Jefferson not to do away with the Bank of the United States because he found it useful. However, his policies were not as consistent as one would assume. Notably, piracy by the Barbary states saw the US go to war with them and ultimately win, and following the Haitian Revolution and the First Bahian War of Independence Jefferson got to work on expanding the US Navy to protect American slavery from foreign intrusion. And seeking to establish American claims of discovery on land in Columbia and Spanish Luisiana, he funded expensive scientific expeditions to them. At home, Jefferson's disgraced former vice president Aaron Burr organized a private army from many sources of funding acquired through contradictory promises, and in 1807 he organized an expedition to conquer Spanish New Orleans to make himself its ruler with the Mississippi-dependent American Southwest absorbed into it. But this expedition was badly-planned and it was swiftly dispatched by the Spanish army, and its main effect was cooling American-Spanish relations. Jefferson had Burr arrested the moment he crossed the Mississippi, and he had him tried for treason. But this was a time when few were sure if plotting secession or conquering foreign territory was treason, and Chief Justice Marshall ignored executive pressure and cleared Burr of all charges. But his reputation was nonetheless destroyed, and Jefferson was more popular than ever by the end of his presidency.

1809-1817: James Madison (Republican)

1808: (with George Clinton) def. Charles C. Pinckney/Rufus King (Federalist)

1812: (with DeWitt Clinton) def. John Marshall/Jacob Stout (Federalist)

Madison broadly continued Jeffersonian policies albeit with a more pragmatic impulse, and he governed in a period of prosperity. He refused to heed calls to renew the Bank of the United States and instead let it lapse and turn into a private bank. Furthermore, Treasury Secretary Gallatin continued to fight against the national debt, and by 1814 it was entirely paid off, to the joy of most Republicans. But some thought the national debt was a blessing which could unite the nation and fund projects, and in 1812 the foremost moderate Republican, DeWitt Clinton, made a run to win the nomination of the congressional caucus. Defeated, he was compensated by becoming Vice President, and they cruised to victory over a Federalist ticket headed by Chief Justice Marshall which, for all of his popularity, was still tainted by the fact that Federalism was worn out. In his second term Madison allowed some adjustment from the norm, including some congressional funding for Clinton's pet project of the Erie Canal, but the largest crisis he faced was a conspiracy to take the Southwest out of the Union - a conspiracy he foiled, but he discovered worryingly that it had support in the army. The semi-detachment and dependency on the Mississippi of the Southwest continued such feelings of resentment, however, and he knew the only long-term solution to this was the acquisition of Luisiana.

1817-1825: James Monroe (Republican)

1816: (with Daniel D. Tompkin) def. DeWitt Clinton/Caleb Rodney (Republican/Federalist)

1820: (with Daniel D. Tompkin) def. DeWitt Clinton/Simon Snyder (Republican/Federalist)

In a congressional nominating caucus, Monroe prevailed over dissenters to Virginia's domination of the presidency, namely Clinton and Crawford. Though he kept Crawford satisfied, Clinton ignored the caucus decision and ran separately with Federalist endorsement. Monroe was immediately faced with the crisis of the Year without a Summer in 1816, and the mass flight of impoverished New Englanders to the greener pastures of the West caused large amounts of public land speculation. The bubble this speculation generated popped in 1819, causing an economic panic, and Monroe's reaction of doing nothing to resolve it inspired disdain. Furthermore, following fighting between Maine and New Brunswick militias over disputed territory in 1818, a war scare erupted between the US and Britain, and it caused the election of War Hawks to Congress. All of this inspired Clinton to launch a second presidential run, with endorsement from the Federalists, on an antiwar platform. He was defeated, but he came quite close. Though Monroe resolved the immediate war crisis, with the opening of war in Europe in 1821 British impressment of American sailors caused perennial crises from which he only wanted to escape. With his diplomatic expertise, he did, but a war-hungry Congress was never satisfied. And all the while, Monroe's goals of ending partisanship floundered. The 1824 election demonstrated this.

1825-1827: William Lowndes (Republican) †

1824: hung electoral college: William H. Crawford/Nathaniel Macon (Republican), William Lowndes/Nathan Sanford (Republican), DeWitt Clinton/Richard Rush (Republican), Smith Thompson/Samuel Smith (Republican)

1865 (with Nathan Sanford) def. in contingent election William H. Crawford/Nathaniel Macon (Republican), DeWitt Clinton/Richard Rush (Republican)

The 1824 election saw the total collapse of the congressional nominating caucus, as it failed to impose its choice; instead states nominated their own slates. The result was a hung Electoral College, and in the subsequent contingent election, a very chaotic affair which resulted in reform (presidential elections were made uniformly popular with their votes consolidated in electoral votes apportioned from "presidential districts" carved by states, electors were abolished as useless, and in the case of a hung college a simple vote of a joint session of Congress from among the top two candidates would decide the president and/or vice president), William Lowndes won. A well-respected War Hawk and Treasury Secretary from South Carolina, he immediately got to work. His new Secretary of State Henry Clay got to work. His plans to go to war with Britain were ultimately pre-empted when Spain closed the mouth of the Mississippi to American access, and as a Kentuckian Clay knew how disastrous this would be. Following a last-ditch negotiation with Spain, Clay pushed for war, and this Congress accepted. American troops immediately crossed the Missippi, and they conquered Saint Louis. They charged to take New Orleans and the lower territory, but Spain's navy drastically outstripped the US's and as a result it failed to hold this territory. Furthermore, the Spanish Navy bombarded cities across the Eastern Seaboard, which the US with its small navy could do little against; in Charleston, Spanish troops landed, looted the city and took its slaves, and they left the city ruined. But the army was still able to conquer Luisiana and the Floridas, finally taking decisive control over New Orleans and St. Augustine. In its wake, Lowndes was able to open negotiations with Spain for peace. But his health, never particularly good, collapsed in 1827, and he died.

1827-1829: Nathan Sanford (Oppositionist Republican)

Following Lowndes' death, his vice president Nathan Sanford acceded to the presidency. He got sworn in as president rather than "Acting President", setting a precedent, and under him the Luisiana War finally came to a conclusion, with the US getting Luisiana and the Floridas in a treaty largely recognized as generous for the United States, despite that Clay had tried to acquire as much as up to the Rio Grande. When some were uneasy at territorial acquisition by conquest, Clay spun it as compensation for the sack of Charleston, which the public accepted in a patriotic frenzy. His tenure also saw the ratification of the Tariff of 1827, a tariff for protection rather than revenue that similarly saw widespread support from the patriotic public. Sanford attempts to assert himself as president largely failed, not in the least because he was a Clintonite and thus alienated from most of his cabinet. That Secretary of State Clay, who was wildly popular, was semi-openly preparing a presidential run, only undercut Sanford's own attempts to push himself in the public imagination; he nevertheless made a run for president, in which he was decisively defeated.

1829-1837: Henry Clay (Republican, then National Republican)

1828 (with John Sergeant) def. Hugh Lawson White/Littleton W. Tazewell (Republican), Nathan Sanford/None (Oppositionist Republican)

1832 (with John Sergeant) def. Hugh Lawson White/John Tyler (State Rights), DeWitt Clinton [died before certification]/Charles Polk Jr. (Oppositionist Republican), John C. Calhoun/Henry Lee (Nullifier), Samuel Morse/William Jackson (Anti-Catholic)

Winning election based on his grand successes as Secretary of State, Clay immediately got to work. With war crises with Britain at an end following its Popular Revolution and its pullout from the European war, he got to work on a treaty. The Calhoun-Tierney Treaty recognized the generous 49th parallel as the border between the US and BNA west of the Lake of the Woods, and the Aroostook dispute was resolving with the US getting all of its claims recognized. Clay re-established the Bank of the United States (albeit in Washington rather than Philadelphia), and public suspicion was assuagedby his arguments that it would end the monetary mismanagement seen in the Luisiana War. Furthermore, he established a system of internal improvements across the nation, most famously with the National Road which linked the eastern port of Cumberland, Maryland to the frontier town of Lowndes, Missouri Territory. In addition, he worked on opening up the Mississippi to navigation and funded a canal from Pennsylvania to the Great Lakes. He wrapped up expanded tariffs, internal improvements, and the national bank in what he called the "American System", an appealing platform intended to make the US a united power to rival Britain. He got to work on expanding the Navy to ensure its catastrophic failure during the Luisiana War would never occur again, and he established heavy funding for the American Colonization Society that sought to settle freedmen to West Africa - funding that ultimately dried up due to a South increasingly suspicious this was emancipation by the backdoor. Furthermore, he recognized Venezuela's independence from Spain and established lucrative commercial relations with it, and he issued the Clay Doctrine that declared the US would support the independence of any state in the Americas from colonial powers.

This all engendered opposition from all quarters of the nation. In particular, South Carolina declared tariffs for protection purposes nullified and threatened to secede. Clay's own Secretary of State, John C. Calhoun, resigned over this and turned almost overnight from a fierce nationalist to the prime nullificationist. In 1832, Clay attempted to resolve this crisis with a compromise tariff after negotiation with Calhoun, but while it did reduce disunionism, it was still alarmingly high, and Calhoun himself dropped his support of the Compromise Tariff following petitions by his constituents. The 1832 election therefore saw a glut of candidates who sought to win a contingent election - Clinton, who realized this would be his last attempt to gain the presidency; Calhoun, who sought the nullification of the tariff; Lawson, who harshly opposed the tariff but not so extreme as to endorse nullification; and Morse, the anti-Catholic mayor of New York, who sought to drastically increase naturalization requirements for immigrants. Over this fractured and regionalized field, Clay had more than enough support to win by a sweeping margin. In its wake, Clay ended the Nullification Crisis with both a Second Compromise Tariff that would gradually lower it and a Force Act confirming his power to crush treason. The Nullification Convention of South Carolina dissolved itself, but not before nullifying the Force Act, and this therefore brought the Nullification Crisis to an end.

And so, Clay continued his efforts to unite the nation. Most famously, he had established the Second National Road from Washington to New Orleans, and he initiated the first American forays into rail. All of this came with large popularity from the public as it coincided with great prosperity. When Missouri applied for statehood in 1836, few thought this would change. But it did when an antislavery congressman proposed an amendment to require it to abolish slavery. This provision passed the House by large margins over the South, only to be defeated in the Senate, and the former made it clear it would stop at nothing to bring up this amendment once more. The result was chaos both in and out of Congress; some even spoke of disunion. Following a second ratification of the amendment by the House, delegates from across the South met in Atlanta to consider further moves - including secession. Clay sought to resolve this grave crisis, and to this end he made a series of remarks. He asserted the "inviolability of this species of property", spoke of the contendedness and "convenience" of slaves in Kentucky, favourably compared the "black slaves" of the South with the "white slaves" of the North, and asked gentlemen if they would "set their wives and daughters to brush their boots and shoes, and subject them to the menial offices of the family". This pro-southern stance, intended to keep the South from going Calhounite, was a break from his public image as an antislavery slaveholder and it caused even greater acrimony, and his own party split over it as the northern National Republicans agreed on a slate of their own. And so, his presidency ended with the union in threat, and nothing he tried was working.

1837-1845: Zebulon Pike (Old Republican, then People's)

1836: (with Peter V. Daniel) def. John Quincy Adams/Richard Rush (Adamsite), Willie Person Mangum/Thomas Clayton (National Republican)

1840: (with Peter V. Daniel) def. Richard M. Johnson/John Davis (Unionist), James G. Birney/Thomas Earle (Liberty)

Formed out of the fractured opposition, the Populists were formed out of Van Buren's great political skills and his desire for a party to be made out of the "plain republicans of the north" and "planters of the south" to avoid sectional tensions, such as were occurring around Missouri, and to represent the "true people". He successfully got both northern and southern anti-Clay men behind Zebulon Pike, whose expedition to Louisiana and, by accident, New Mexico and beyond, and whose later role in conquering New Orleans for the third and final time made him a great hero, and this ticket won over the fractured northern and southern National Republican slates. That he was a Kentuckian like Clay was a coincidence that only made his victory much more sweet for anti-Clay men. But the Missouri crisis continued to coarse through the United States, the Atlanta Convention treated itself more and more like the embryo of a new state, and people on the street spoke openly about disunion. To resolve this crisis, Clay got himself elected to the House of Representatives, and through his mastery of parliamentary procedure and with the support of doughfaces elected along with Pike, he then wrote up the Missouri Compromise. In return for slavery to its south being expressly assured, a stronger fugitive slave law, and Indian removal, slavery to Missouri's north and west was to be forever forbidden, and in Missouri itself additional importation of slaves was also to be made illegal. Clay successfully got this compromise through, and despite Missouri later going back on the promise to forbid additional importation of slaves and doughface northerners seeing defeat after defeat in the 1838 elections, it stuck. And the Atlanta Convention dissolved itself after approving the Compromise, despite Calhoun speaking of restriction being war on the South.

When France refused to repay money for its raids on American commerce, relations between France and the US got much chillier, and when France forcibly searched American merchant ships illegally trading slaves from Portuguese Mozambique to Portuguese Brazil, this resulted in Congress authorizing Pike to take military action in 1839. This began the "Second Quasi War", which saw support from both among Populists and National Republicans. But the war continued on and on, and with the low Compromise Tariff this resulted in a government with little revenue spending lots of money, resulting in it going into more and more debt despite all of its anti-debt stances. And the war's popularity was in question. In 1840, both sides of the National Republicans, as well as a host of other anti-Pike politicians, united in the form of the "Union Party", whose expressed aim was to avoid all disunionism but in practice was a wider version of the National Republicans. In 1840, its nominee, Richard M. Johnson, did not exactly show his party in the best light. He gave erratic speeches on the campaign trail, and his common-law marriage with his slave Julia Chinn alienated him in the South. The Unionist platform of peace with honour fell down the wayside. Ultimately, Pike cruised once more to victory. He brought an end to the war in 1842, with the US reiterating its agreement to fight against the slave trade and France agreeing not to search or seize American ships.

But the lustre of winning the Second Quasi War did not last very long. Overspeculation in the new Luisiana territories had created a bubble, heavily fostered by Clay's roads and canals easing settlement, and Pike's policies only increased it as he freely distributed land to squatters, which filled land at a much quicker rate than the state could open up more for settlement. The bubble then popped, and the result was a massive panic. Though Pike and the Populists tried to bring this ire towards the Bank of the United States which had, indeed, greatly contributed to the bubble, this effort failed. For one, that Pike had already opposed the Bank on principle diminished his credibility to speak on this issue. Furthermore, the Bank was more than willing to do everything it could to diminish the panic, even if it meant putting itself in debt, and this contrasted with state-level Populist-aligned banks which only enlargened the scope of the panic by calling in loans and reducing credit to stay solvent. All the while, Pike's laissez faire lack of a response was greatly alienating. With his legacy as president in tatters, his party cratered to defeat.

1845-1852: Daniel Webster (Unionist) †

1844: (with Edward Bates) def. Martin Van Buren/John Tyler (People's)

1848: (with Edward Bates) def. John C. Calhoun/Silas Wright (People's), James G. Birney/Leicester King (Liberty)

Daniel Webster was a most unlikely president in an age of mass politics. He was a former Federalist, a party well-known for its elitism, and he himself had inherited much of that elitism. After making his entry into Congress as part of New England's rage at the Year Without a Summer, he was against war with Britain which he thought economically ruinous for the New England for which he was always identified. But he was all for war with Spain following its closure of the mouth of the Mississippi as he recognized its potential to destroy American commerce, and it was after this that he became allies with Clay and other War Hawks. As a Senator for Massachusetts, he was a close ally of Clay. But he truly became a national figure during the Nullification Crisis when, following a particularly harsh speech for nullification by Calhoun, he replied in a speech with great eloquence in defence of the Union. Webster's Reply to Calhoun was published across the nation to be read by an excited public, and it immediately became a legendary feat of rhetoric and eventually the virtual manifesto of the Union Party. In its wake, Clay made Webster his Secretary of State, and he served quite well in that post, successfully escaping the acrimony over Missouri by being involved in diplomacy for the duration of the crisis. In its wake, he returned to the Senate and opposed Pike's agenda with skill - though he did rally to the Second Quasi War. All of this made him prime material for the presidency despite all of his New England particularism, and he had the ambition for it. Running in a year of certain Unionist victory, he predictably swept his way into power.

Initially, he faced the fact that his party was unofficially led by Senator Clay, who attempted to dictate cabinet appointments. Webster refused to accept this dictation and appointed Thomas Ewing his Secretary of State and James Wilson his Treasury Secretary - both of whom were not Clay men. But nonetheless, Clay continued to serve as the leading legislator of the United States. With the low tariff making it hard to fund the government and protection being the great Unionist policy, Webster immediately pushed through a new tariff. But in a major break with the American System, he established a trade reciprocity treaty with British North America, as under the low tariff very strong trade links had been established between the North and BNA. Furthermore, he established renewed internal improvements across the nation, and particularly he focused them across the rapidly growing Midwest. And he believed the US needed a Pacific port to open up American commerce across the Pacific, and thus focused himself on that great project. First, he attempted to acquire San Francisco from Spain. However, he was harshly rebuffed no matter how much money he tried to leverage, as Spain believed this would be a stepping stone to the conquest of California. Next, he looked to Britain, with whom relations continued to be friendly ever since the Popular Revolution, and after much negotiation he got it to agree on the purchase of the Olympic Peninsula, including its many natural ports. This was, he knew, a territory dependent on the Columbia territory being friendly if not under American rule, and to that end he carved out trails reaching up to the Rockies to ensure that Americans would settle it and thereby make it friendly. And indeed, young men did in large numbers move to this territory, joining the many paupers and indigent who the British government sent to relieve its stresses. This great success of diplomacy, however, was ultimately overshadowed when, with southerner support, a filibuster attempt into Cuba, was launched and failed. Not one to accept such a blatant violation of law, Webster harshly prosecuted those responsible. With his reputation already as antislavery, this alienated many southern Unionists, and this struck in election year.

The 1848 Populist nomination was won by John C. Calhoun, who moderated many of his positions up to and including endorsing internal improvements, and he successfully beat out Van Buren with the western support this gave him. He narrowly averted a Burenite split by promising not to renew the national bank and agreeing in writing to cabinet appointments, and his newfound support of internal improvements appealed heavily to the west; it gave him a surprisingly strong position. In addition, he spoke favourably about Spanish Texas, speaking of linking it with the US and hinting at acquiring it. It put a chaotic issue on the table, which threatened to greatly strengthen the Populists in the South. This led Webster to firstly seek to appeal to southern votes and moderate his position on slavery further, alienating some of his abolitionist supporters, and secondly to endorse a Homestead Bill in a clean break with Unionist land policies but which highly appealed to the west. On this basis Webster won the election decisively, but narrower than many would have hoped considering Calhoun's former nullificationism. He then got passed a Homestead Act, which proved very popular in the west, but as it settled large swathes of land with northerners and in practice discouraged slavery, it made the south unhappy.

Webster's popularity would run out when directors of the Bank of the United States were revealed as artificially inflating stock value for the sake of dumping them at their peak. That Webster had, before being president, been on the Bank's legal retainer, and that a fellow New Englander Nathan Appleton was its president, led many to accuse him personally of corruption. Initially he did nothing about this report, but when it got confirmed, he was forced to push for new directors and got the accused to resign, including replacing Appleton with the Baltimore Unionist Reverdy Johnson as Bank president. This only made him look like he was covering up his own dirty hands, and his popularity promptly crashed. Furthermore, in 1851 in Spanish California a merchant discovered gold, and this caused a massive gold rush. The large involvement of Americans in this caused a flow of gold into the United States, which gave it a solid currency utterly undependent on bank notes, and it made the Bank look useless. The subsequent boom this caused was one for which Webster and the Unionists got no credit for whatsoever, and they diminished in stature. Webster would ultimately not live to see his party defeated, for in early 1852 he died of liver cirrhosis.

1852-1853: Edward Bates (Unionist)

Following the Sanford precedent, Bates got himself sworn in as President. He attempted to fix the Unionist situation by distancing himself from the Bank and reiterating the dogma of national unity. But he didn't have enough time to push himself in the national consciousness, and though he did get nominated by the convention, he lost decisively.

1853-1861: Robert F. Stockton (People's)

1852: (with Thomas Jefferson Rusk) def. Edward Bates/Rufus Choate (Unionist), John P. Hale/Leicester King (Liberty)

1856: (with Thomas Jefferson Rusk) def. John J. Hardin/William M. Meredith (Unionist), Sidney Egerton/William Goodell (Free Democracy)

Stockton had previously served as a naval officer. Leading the conquest of Cape Montserrado for the American Colonization Society, he made his name during the Luisiana War where, against a much larger navy, he achieved a number of successes. In its wake, he was involved once more in the American Colonization Society, up until the Second Quasi War when its African colony voted to join British Sierra Leone to avoid feared French raids, and instead he was involved in daring raids on the French Caribbean. In its wake, he became Pike's Secretary of the Navy, and afterwards he became a senator who made his name on naval reform and represented a moment of national pride. All of this made him prime material for a presidential candidate, and in the year of 1852 he won the nomination and swept his way into the presidency. In power, he was surprisingly pragmatic. He was willing to endorse internal improvements as much as any Unionist, except that he believed it should back fully-private companies rather than the public-private partnerships that were the norm, and this fostered the rapid development of railways across the nation - railways in whose stock Stockton personally held much in. Furthermore, he launched the navy around the world, which made tours in Europe and joined Britain and France in opening Japan and China. And personally, he spoke of international revolution, pitting the United States decisively on the side of liberty in Europe's great struggles. He also focused on the Bank, and he regarded it as a bad investment for the American people - its close affiliation to the Unionists did not help. With the California Gold Rush drastically diminishing the need for Bank notes, it was forced to call in loans and retrench, resulting in economic chaos. Stockton thus planned for another place to put government deposits, and he made his views known. Furthermore, he advocated expansion into Cuba and Texas, not in the name of the southern planter interest but simply because he believed it was America's manifest destiny, and he even advocated expansion into California with an expressed end goal of covering the entirety of North America. On this hyperexpansionist platform, as well as in the name of killing the Bank, Stockton won sweepingly, although the Free Democracy, a rebranded version of the abolitionist Liberty Party, won electoral votes which caused acrimony among southerners upon certification.

Over this, Stockton decided to dissolve the Bank. Its attempt to renew its charter - 12 years behind schedule - to avoid its own dissolution, failed and it only made it look farcical. He then pushed through a plan to create a National Exchequer, run by a board with the Treasury Secretary, the Treasurer, and three presidential appointees requiring congressional approval. Its role would be to look after government deposits and print promissory notes with a fixed 1.5:1 ratio in a much more sharply state-driven manner. With its ratification, Stockton removed deposits from the Bank and put it into the Exchequer. With that, the Bank was defeated, and Reverdy Johnson was forced to accept this. However, it lingered on, for its charter was to expire in 1869 - and by that time the Union looked quite different indeed. Furthermore, Stockton endorsed filibusters in Texas and Cuba, and in an attempt to attract the north he claimed them to be attempts to halt the trans-Caribbean slave trade. These filibusters ultimately failed, despite their vast scale, as they did not gather the popular support necessary to succeed, for Cuban planters believed Spain was necessary to keep the slaves from rebelling and the Hispanicized Irish of Texas were not particularly pro-American. And Stockton lacked the support to go to war with Spain. Furthermore, the railway bubble Stockton aggressively supported popped after a number of unprofitable ventures failed, and this combined with a slowing of California gold ending core economic assumptions to cause an economic panic. That Stockton had invested in the railways that remained sound led to talk that he was personally corrupt. Despite the internal weakness of the Unionists, ultimately this devastated Populist popularity and brought it to the nadir. Thus, like Pike, Stockton left office under a cloud.

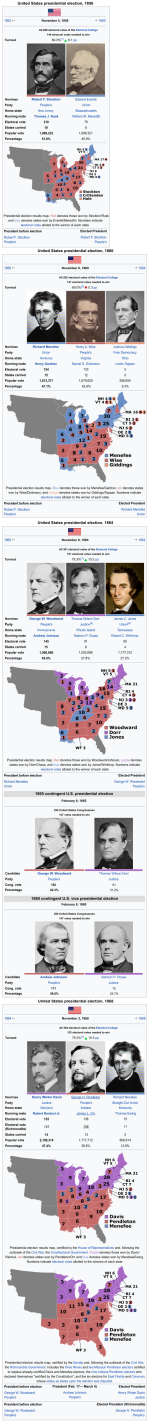

1861-1865: Henry Clay Jr. (Unionist)

1860: (with Henry Gardner) def. Henry A. Wise/Daniel S. Dickinson (People's), Joshua Giddings/Lewis Tappan (Free Democracy)

In the shadow of his much more famous father, Senator Clay Jr. won the presidential election with surprisingly narrow margins and despite the Free Democracy doing quite well with a candidate who cut into the Unionist vote. But Clay Jr. was faced with a Union Party faced with the loss of its cohesion, as the Populists stole its clothes over internal improvements, and the Exchequer proved more than popular among Unionists as a purified pseudo-bank. Therefore, an attempt to abolish the Exchequer and move deposits back to the Bank floundered. On the other hand, the calamitous end of Railway Mania made a Congress extremely suspicious of internal improvements and resulted in it putting new plans under harsh review, and Clay Jr. lacked the parliamentary mastery of his father that would have allowed him to get it past that. That he all the while had a Unionist Congress only made the situation even more farcical. Thus, other than the restoration of the Neutrality Act, Clay Jr. got nothing through. The 1862 elections continued this, as the Unionists faced losses to both the Populists and the Free Democrats - the latter resulted in slavery entering the national stage despite Clay Jr. being, like his father, an antislavery slaveholder. But at the end of the day, party was losing its cohesion on the national level, and this felled the Clay Jr. presidency.

But this would all be overshadowed in 1864 when, following an extended crisis, the Provincias Internas of New Spain, consisting of Texas, New Mexico, California, Sonora y Sinaloa, New Vizcaya, Coahuila, New Leon, and New Santander, declared their independence as the state of Buenaventura under a decree which abolished slavery. This inaugurated a war of independence, and that Buenaventura was abolitionist brought it into conflict with the Cuban planters of Texas which inevitably caused immense opposition in the South, even as the North was electrified and many young northerners joined up with the Comuneros fighting for its independence. Clay nevertheless endorsed its independence in accord with the Clay Doctrine of his father. American support of Spanish American states' independence, even of expressly abolitionist states, had hitherto never caused controversy, but in this case it suddenly did, for it was next door. And Clay Jr. opened this divide into a chasm through his words. Wisely, he chose to bow out in the Unionist convention, but its failure to pick a Northern candidate only caused the Northern Unionists to bolt and join up with the Free Democracy to create a joint slate. Suddenly, the Union was in threat, and the Union Party was split at a time when the Union itself was at the seams. The next election only ensured this split would be permanent.

1865-1869: George Washington Woodward (People's) [impeached, removed from office]

1864: hung electoral college: George Washington Woodward/Andrew Johnson (People's), William H. Seward/Salmon P. Chase ("Justice"/"Free Soil"/"Republican"/"Liberationist"), Alexander Stephens/Robert C. Winthrop (Unionist)

1865: (with Andrew Johnson) def. in contingent election William H. Seward/Salmon P. Chase ("Justice"/"Free Soil"/"Republican"/"Liberationist")

Woodward had, prior to his nomination, served as Chief Justice, and his politics' very obscurity was the entire reason he was nominated. With the Unionists divided between the technical southern-dominated ticket and the antislavery slate so hastily-established it had separate party names in separate states, most were confident that Woodward would cruise to victory. But he didn't, and instead the College was hung, sending the election to Congress. Due to Southern Unionists voting for Woodward, Woodward was elected president by a joint session of Congress, in addition to his vice president Johnson similarly winning election. His obscure politics helped him to achieve this. But in power, he showed his true self. He was not only a doughface, but his opinions verged on Calhounism. He openly endorsed slavery despite being a Pennsylvanian. He overturned recognition of Buenaventura and called for its rebels to stop disturbing the peculiar institution. But this didn't stop northerners from joining the Comuneros and thereby strengthening them. To stop this, Woodward enforced the Neutrality Act to its fullest against them, and he was willing to arrest people if necessary. At the same time, he ignored Southern support of the Spanish was effort. In and out of Congress, the Buenaventuro War of Independence and the American response became a topic for discussion, even as Woodward tried to clamp down upon it. His attempts to indict Comunero rebels only ended with northern juries nullifying the law. And in Congress, nothing Woodward tried could stop antislavery congressmen from discussing slavery.

When Senator Joshua Giddings made a particularly extreme speech condemning slavery and defending Buenaventura's fight, Senator Henry Foote of Yazoo shot him dead on the Senate floor, and a Washington court gave him a remarkably light punishment for this act of murder. The result was outrage across the North. But none of this stopped the victory of the Comuneros, and with it seeming imminent, the South sought to secure slavery within the borders of the United States. In a court case over a slave suing for his freedom, the Harris Court declared that Congress had no power to regulate slavery, a ruling which implicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise and, in the absence of congressional law, reactivated the old Spanish law allowing slavery from Kansas to the Rockies to Minasota. Woodward accepted this ruling despite its implicit extremism. Furthermore, to secure slavery once and for all, Woodward sought to admit slave states. East Florida and Cimarron requested admission and, despite not meeting quotas for statehood population, they were nevertheless allowed to hold referenda which, thanks to non-resident voters, "proved" both had the population to be admitted as states. Through the use of executive patronage, Woodward got the statehood of both through Congress. Furthermore, he inaugurated settlement in Kansas which saw both North and South aggressively push settlers into it and fight literally for its admittance as a free or slave state, with the territorial governor and council fighting unabashedly for slavery. In the subsequent congressional elections, the antislavery forces, consolidated following the contingent election fight as the "Justice Party", won a majority in the House and nominated a Justicialist as Speaker. In retaliation, South Carolina pulled its House delegation from Congress, and this made disunion even more thinkable than before. When Buenaventura won its independence in 1867, Woodward refused to recognize it as anything other than a rebel government, and Northern volunteer returnees' establishment of "Comunero Clubs" which served both as paramilitaries and Justicialist campaign headquarters, and southerners replying by establishing "Minutemen" groups to play the same role for them, only worsened tensions. Warfare in Kansas became much more brutal than before. In the 1868 election, Woodward's own party refused to nominate him, southerners preferring a southerner to a pro-slavery northerner, and ultimately in 1868 it happened. The Justicialists won.

Declaring the election illegitimate, southern notables declared hatred and semi-openly plotted secession. Outgoing, Woodward nevertheless sought to aid the south as much as possible. He cast doubt on the election and accused Comunero Clubs of rigging it, and he plotted with the most extreme southern voices. He made sure pro-southern men were in control of important army equipment and he semi-openly committed sabotage of a potential northern war effort. And finally, on February 10, 1869, Minutemen from Virginia and Alexandria stormed Congress after overpowering the weak military presence, interrupting the certification of election results, and they then ransacked the Capitol and destroyed the certification papers. Under their guard, southern and some doughface congressmen met and, despite failing to meet the quota, they creatively interpreted Article I Section V to give them the power of expelling nonattending congressmen to reduce the quota necessary to be a valid session of Congress. They threw out election results on the pretence of interference and, in a "contingent election", certified the southern candidate as the winner. The Justicialists replied by organizing a session of Congress in Philadelphia which in contrast met quotas for validity and certified the election's legitimate winner. It impeached Woodward and removed him from office and allowed his staunchly constitutionalist vice president to take power for the two weeks until March 4. But everyone knew this was only the beginning of a great fight for the nation.

1869-1869: Andrew Johnson (People's)

Johnson's rise was only accepted by the Philadelphia Congress - indeed, the Harris Court declared it illegal and its judges then got removed from office by Philadelphia - but nonetheless he organized military preparation. He revoked territorial governors and replaced them with Justicialists. In Kansas, this caused a miniature revolution when its proslavery governor and territorial congress were overthrown in revolution by local Comunero Clubs, bringing about a border war between it and Missouri. In New York City, its mayor declaring against the Philadelphia Congress caused him to be overthrown by local Comuneros, an act which caused vast riots across the city which damaged the war effort. While most slaveholding states refused to recognize the Philadelphia Congress, Johnson made sure that Delaware and Maryland recognized it, though he could not stop Baltimore from falling to slaver gangs. The landlocked and slaveowning southern-dominated midwestern state of Illinois saw more division as its governor refused to recognize Philadelphia, but Johnson secured the assent of its congress, which ensured that Illinois would see a civil war rather than a fall. By the time of March 4, Johnson ensured there would be a government for prosecuting a war for the constitution.

1869-1877: Henry Winter Davis (Justice)

1868: (with Robert Rantoul Jr.) def. William M. Gwin/Jefferson Davis (People's), Henry Clay Jr./Thomas Ewing (Straight-Out Unionist)

Note: After a mob occupied the capitol, a rump Congress convened on February 10, 1869, decertified the results of the 1868 election, and in a "contingent election" declared Gwim as president

1872: (with John Cochrane) def. George H. Pendleton/Rodman M. Price (People's)

Davis was an unlikely figure for an antislavery party, for he was a Marylander and a supporter of the ideals of Henry Clay. He was, while antislavery, an enemy of "rabid abolitionism". But nonetheless, as Senator he aggressively supported Buenaventura right until the state government forced him to resign, which made him a hero to the Justicialists. Returning to Congress as a Representative, he continued this effort and quickly became the most notable Justicialist south of the Mason-Dixon line. Opposing Kansan slavery, his position only strengthened further and, with the Justicialists recognizing they needed to portray themselves as moderate and non-sectional, he won nomination at the 1868 Justicialist Convention. He won election by sweeping the North, even while losing his native Maryland. But despite him being a Southerner and a moderate, it wasn't enough to stop southern extremism, and following the takeover of the Capitol by Minutemen, he organized a Congress in Philadelphia to create a constitutional national government. It inaugurated a long and difficult war, but ultimately the Union and Constitution prevailed. And the exigencies of war changed Davis greatly, turning him from a moderate to a radical, to the surprise of everyone.