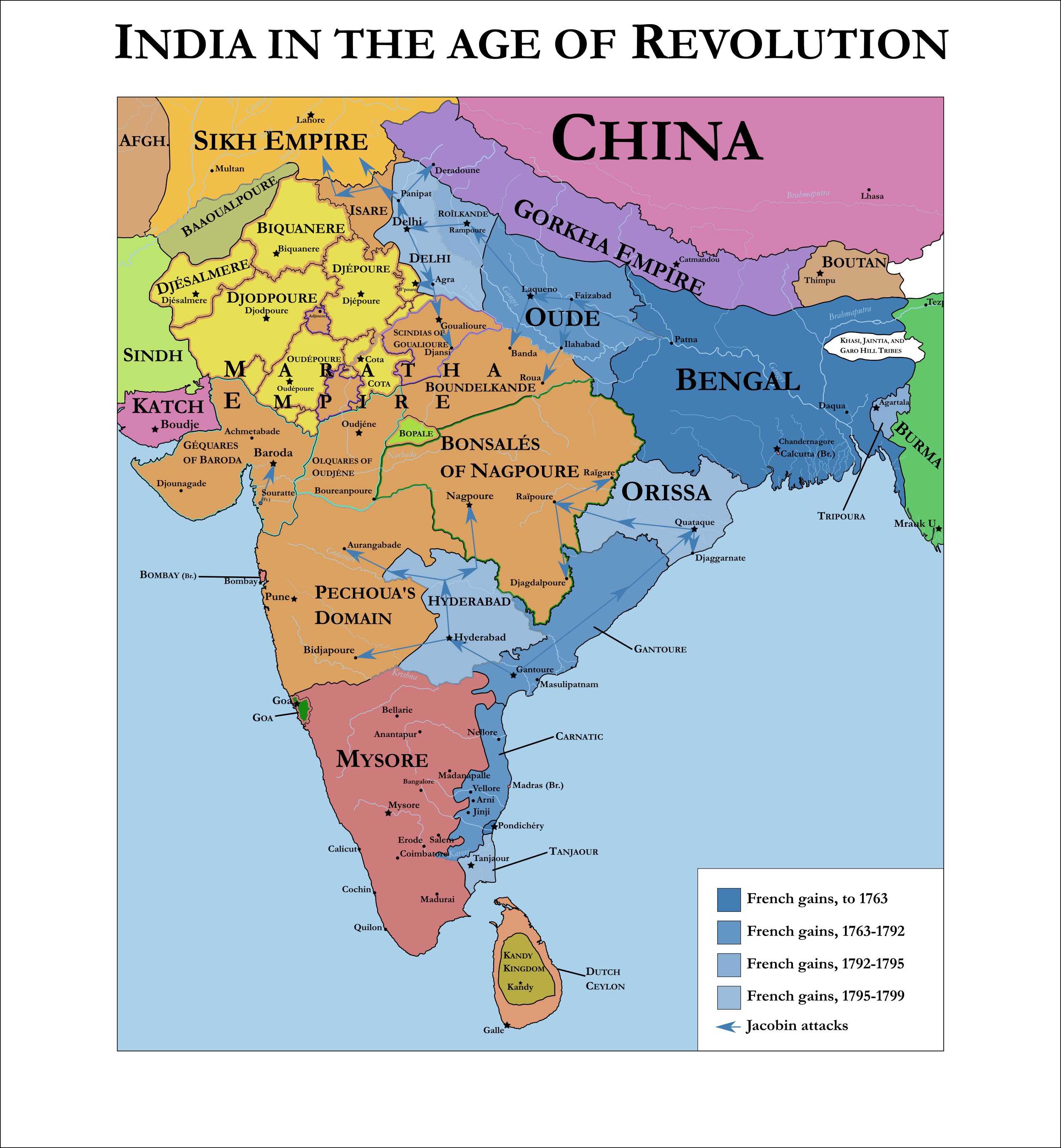

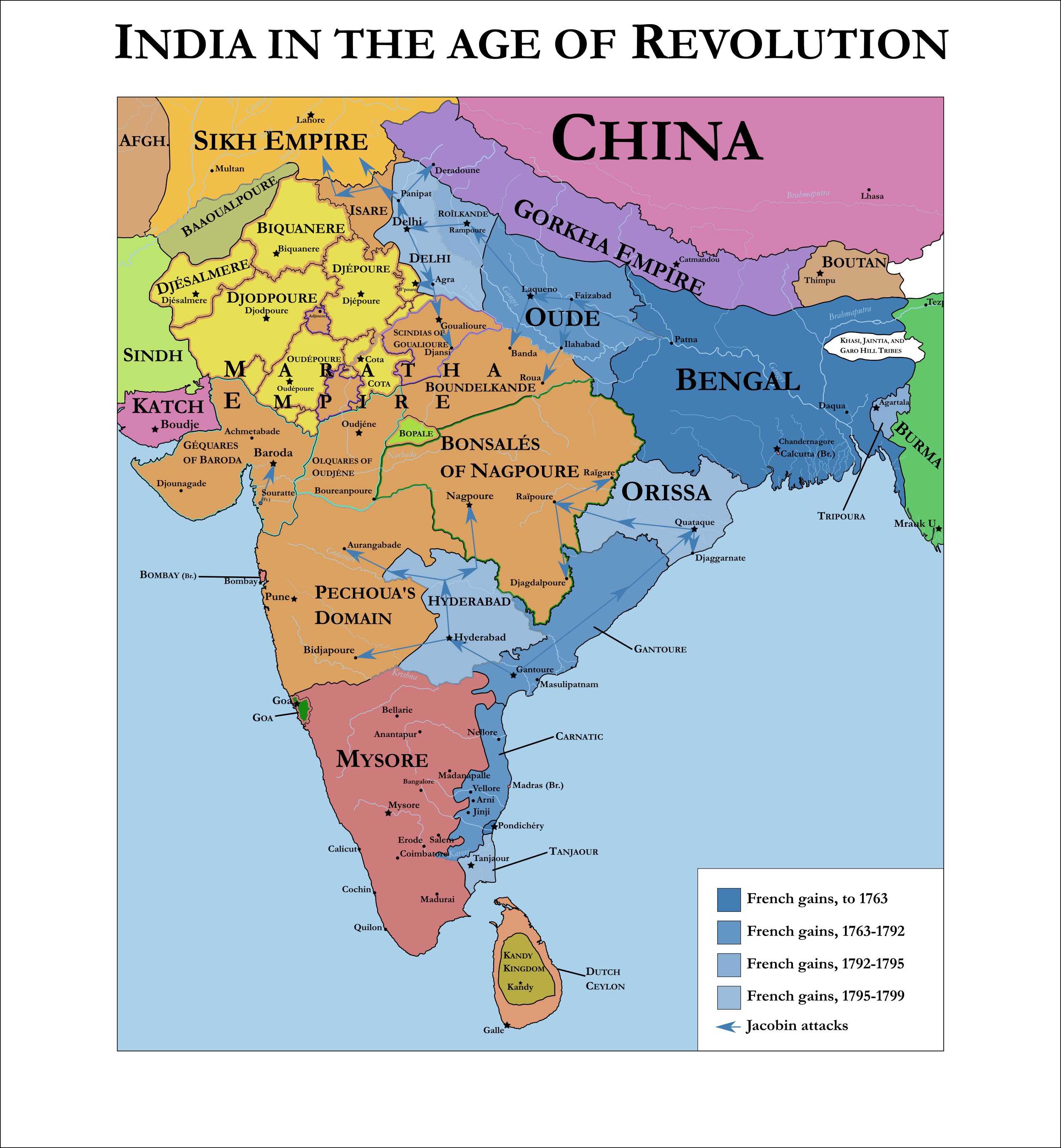

France long had a presence in India, but it would only be following the Seven Years' War that it truly had an empire in it. With the decisive defeat of the British in that theatre (even as it lost outside India), France suddenly not only governed numerous ports, but also Bengal through a puppet. Only a few years later, in 1769, it would also gain vast influence in Oude with recognition from Delhi and, with support from Mysore's effective ruler Hyder Ali, over much of South India. When the Nabob of the Carnatic, in alliance with the British, attempted to overthrow French encirclement in the 1770s, it was slapped down hard, French and Mysorean troops swiftly descended onto the capital and in 1779 the Carnatic was divided between Mysore and France. This gave France influence over Tanjoure as well. But increasingly the French aimed at enlargening their influence over Hyderabad, and using its ties with the British as a fig leaf it then went to war with it and, by 1786, French troops successfully forced the Nizam to grant them the entirety of Hyderabad's coastline, and the Marathas ate much of its remainder. And so, by 1789, France now had a vast empire in India, a land it understood little.

But 1789 was also the year of the French Revolution. At first, it had little effect on India, and though the election to the Estates-General saw some Bengali

badraloque elites advocate a right to vote in these elections, they were monopolized by whites. And even at this early stage, there was some Oriental admiration of India in France, with the Bagaouade Gita receiving praise from some radicals - radicals who had barely read it. But then in 1792 came the declaration of a republic, and this all changed. Suddenly, the French armies in India mutinied against their royalist commanders, killed them with fresh new guillotines, and with support from Paris, they now led India. Initially Indian feelings were that these new bosses would be little different, but they were quickly affected by revolutionary temper. When the puppet Nabob of Bengal attempted to use this opportunity to rebel against his masters, he was not only discovered, but he would be publicly guillotined, an action that shocked many; they would be even more shocked, when the governor declared the end of Indian monarchy and the establishment of a republican order under French protection. It destroyed the existing axes of legitimacy and replaced them with something new. When the Nabob of Oude arrested the French solders "protecting" him to prevent himself from suffering the same fate, a French army came from Patna and removed him from power; the bulk of his court was executed by public guillotine.

Now truly in charge of a giant swathe of India, the Jacobins now had to interpret India's societal structures in their own term. India contains a complex social institution known as

djati focused around hereditary occupation, each of which with differing social status within their immediate community, and this was conceptualized and stitched together in a variety of ways such as the

ouarna system of fourfold division of society in ancient Indou texts, as well as dubious claims of foreign descent. While many French people previously perceived this as a racial system, calling it caste in analogy to the Spanish system of race, to the Jacobins this was nothing more than an Indian system of "barbarized" guilds. And so, as part of the declaration of abolition of the guilds, so were

djati. French officials entered village after village, and declared their end; when villagers resisted, they often sent in the army to force them to submit, and if they refused, the leaders of

djati councils found themselves guillotined. Furthermore, the turban which often displayed social status was declared abolished, in favour of the egalitarian Phrygian cap of "republican honour". This was all continually enforced by the French, who substituted

zamindar tax collectors for themselves. This caused widespread social chaos and realignment, as well as the sudden rise in banditry. With the abolition of Christianity in France and the rise of the Cults of Reason and the Supreme Being, the institutions of the French empire in India got weirder. Invocations of the Virgin Mary by the state were replaced with invocations of the Indou war goddess Dourga, and in accord to the Radjepout practice guns were blessed in her name. The name of the Indou god Parchouram, who killed much corrupt aristocrats in his stories, was viewed as a corrupted memory of a Cromwellian heroic figure from antiquity, and he was quickly idolized by the French. While the Goddess of Reason was quickly conflated with the Indou goddess of knowledge Sarasouati, and Temples of Reason quickly became non-idolatric temples to her. At the same time, the deist Cult of the Supreme Being was often associated with Islam, a true Islam in contrast to the obscurantist Sufi-inflected Islam of India; when knowledge of Wahhabism came, it was arbitrarily and illogically conflated with this deism. Understanding Islam little, famously the French attempted to commission a great statue of Muhammad from Muslim stone masons; this laughable understanding of Islam caused massive riots. These new movements confused many Indians, utterly befuddled at these interpretations of their religions, while the French zeal to spread them caused revolt that was crushed harshly.

Furthermore, French rule saw new law. During the pre-revolutionary period, to make sense of the "heathen" Indou religion, France sought its original texts, and it believed it found them in the form of the Manousmriti, an ancient compendium of various laws from different ancient states. It contradicted itself, notably both restricting divorce and providing procedure for it, but this was often held up as such. With the rise of Jacobinism, its inherent inegalitarianism saw many view it as a decline of India's "original" republicanism of the Indou god Crichena, who they believed to be a distortion of an ancient republican of his Iädoua clan. And so, inspired by drafts of civil codes coming from Paris, the Jacobins issued "Les loix de Manou originales", meant to be the "original" Indian law. This law had, in truth, little connection to anything Indian, and its implementation confused many Indians even as customary courts were forcibly abolished. But as Indians were forced to go to these courts, they had to understand this law and conceptualize them in their terms; this would have a lasting impact as they morphed in translation into Indoustani, Telougou, and Tamil and changed meaning.

But even as French India was a deeply and utterly chaotic land in this era, many sought to expand the revolution. And so, soldiers utterly uncontrolled by the central government quickly entered the kingdom of Roïlkande, bordering French Oude, and conquered it. Influenced by conceptions of the "Frankish yoke" of a German-descended aristocracy over the Gallic-descended French people, it did this in the name of overthrowing the "Pachetoun aristocracy" of the land. In practice, however, the new guillotines they established killed Indian-descended and Pachetoun-descended aristocrat alike, and flight from the French advance was just as diverse in nature.

With the rise of the Directoire in 1794-5, this chaotic realm was brought under control. New centrally-appointed governors were sent to rule over the land, along with new soldiers under their command. They aimed at centralizing the French empire in India, but this also necessitated removing Jacobin soldiers. With many being unwilling to lose their status as fiefs, they quickly fled the advance. Many soldiers joined up with native states, leading the charge in reforming and modernizing their armies. Others, however, sought to establish their fiefdoms elsewhere. And so, in this period, Jacobin invasions occurred in Hyderabad, although they failed to conquer it, and instead it came to French forces following them. Others invaded Orissa, under weak Maratha control. The nominal "republic" they established saw many of the chaotic reforms, but in addition came a special focus towards the city of Pouri's famous idol of the Indou god Djaggarnate and the famous festival where it was put on a chariot dragged by devotees. This was viewed as characteristic of Indou "heathenness", while many Europeans believed due to nonsensical accounts that this festival included human sacrifice on the chariot's wheels. As such, the new Jacobin authorities declared the end of human sacrifice in this festival; this, few noticed because no such human sacrifice existed. But, it quickly became more radical. The sacred wooden idols of Djaggarnate, destroyed annually and replaced with replicas, was Jacobinized and now it was topped with a Phrygian cap. This scandal, of tainting with representations of the divine, caused a municipal revolt removing the Jacobins from the city. But also came French troops following the Jacobins, and they swiftly occupied Orissa. They declared the Djaggarnate rituals could proceed as normal.

But the most horror came when Jacobins, pushed out of Roïlkande, crossed the Ganges and Djamouna. Here, they conquered Delhi itself and declared the end of the Mughal Empire and its replacement by a "republic". Most infamously they executed Chah Alam II by guillotine, an event that causes shock. Though he had already been blinded by the Roïla Pachetounes in 1788 and he was a Maratha puppet afterwards, this shocked virtually everyone. Even Tipou Sultan, the firm modernizing French-allied ruler of Mysore who was known as the only Jacobin king, who established a puppet republic in Goa, and who routinely mocked the Mughals for their weakness, was shocked and horrified by this, and almost universally there came a call for their overthrow. And this the French swiftly answered, invading Delhi before the Marathas could answer sooner. Here, they declared that the Mughal Emperor could resume his rule over Delhi, and across India as a spiritual ruler. But the shockwaves continued to shatter across India, and most notably the Marathas refused to recognize this and those territories they nominally held on behalf of the Mughal emperor they now declared held in their own right.

But at the same time, the Directoire continued the bizarre structures of legitimacy that were established. Durga continued to be evoked in places where the Virgin Mary would be, and the new Temples of Reason and of the Supreme Being were not tampered with. The Jacobin understanding of the Indou religion continued. But this period saw the growth of one thing in particular, Masonic temples. But in India, they were understood as temples in the religious sense, focused on a theology of parables centred around a formless god and the character Solomon, and they quickly misunderstood this as quasi-Muslim. Inevitably, Freemasonry was considered a Sufi-Baqueti order by Indians. Many Indians, with this understanding, established their own Masonic temples. And thus began a new religious order.

In 1799, the Directoire came to an end, and in came Napoleon Bonaparte at the head of a vigorous new order. He sought in general to run society in an ordered model, meshing together new ideas with the old, and in India, this was no exception. Seeking to end the religious confusion, he declared the inauguration of a Choura of Indous and Muslims in French territory, headed by the Mughal emperor, to agree on law. In practice, this consisted of clerics who responded to him. They then ratified a new law code presented to them, already written by French-aligned Bengali

badraloque. Notably, it declared the Mughal Emperor both the Caliph and

Indoupati (Lord of the Indous) of India, simultaneously a conservative and revolutionary gesture seeking to conciliate the Sufi-Baqueti nature of resistance. Furthermore, banditry was resolved by the French administration, while Jacobin soldiers still in territory were forced to surrender or leave. This, however, caused yet more widespread chaos. From Hyderabad, Jacobin soldiers brutally sacked Nagpoure and Aurangabade, until their nonexistent lines were destroyed. From Delhi Jacobin soldiers sacked Goualioure and in that they helped cause the decline of the Scindias; an attempt to do the same in Radjastane was stopped by Djachouante Rao Olquar of Indore in the massive Battle of Baratpoure, widely compared to the Maabarata in sheer scale. And other French soldiers simply deserted and joined the Sikh Empire.

Yet, as Napoleonic control proved decisive, colonialism was now restored to full force, to a new generation. The famines of the pre-revolutionary era, caused by state policy of cash crops and export, saw a vicious return, and in this manner they likely killed far more people than any Jacobin fief. The destruction of the

djati system was in practice replaced by pure French overlordship, proving far more unequal in every way. The new religious sentiments continued to proliferate and they often gained radically different form; increasingly they were directed against the French. Because the French attempted to replace it with the bicorne, the Phrygian cap became a symbol of the values of liberty, equality, and fraternity, even if those ideas were understood in quite different terms. And so, underneath the surface there was an anger at the French. It must come to no surprise, therefore, that in 1814, when King Louis XVIII called many French solders from India to protect his regime, the colonial regime entirely collapsed; when Napoleon did the same to more soldiers as part of his Hundred Days, French rule withered away outside main ports. With the collapse in power caused by the end of French rule, the hole was filled in part by the Maratha Empire and by Mysore, but also by something else - Sufi-Baqueti-Masonic quasi-republican monarchies. Thus, India would never be the same.