So, this isn't FTPT, the margin of victory isn't important in establishing safe seats. .

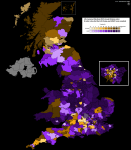

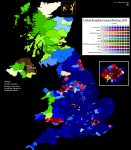

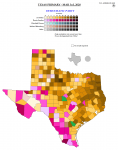

Quite the opposite. The margin is both more intuitive for those used to FPTP (not 'FTPT') maps and the margin between the leading party and the next highest

is extremely important in determining the outcome of a party-list PR election. Let's take Scotland as the obvious example. The SNP got 37.8% of the popular vote, but half (3) of the MEPs. They did this because the other competing parties were way behind them and uselessly split the vote too many ways (the nearest being the Brexit Party on just under 15%). If the SNP had got 37.8% but the next highest party had got, say, 30%, then the SNP wouldn't have got half of the MEPs, which is intuitively indicated by a paler majority margin--but a popular vote map would show the same 37.8% either way.

Or say there's 3 seats on offer, one party has 35%, the next has 34%, and the others are useless divided scattering (11%, 10%, 10%). If you do a popular vote map then party A looks the same as party B because they'd both be in the 30% range. But party A gets twice as many seats as party B, because the D'Hondt formula gives one seat to A, then one seat to B, then the next biggest is less than A's vote divided by 2 so A gets the third seat. The margin is what mattered, not the popular vote range. Of course, it's still not perfect because it only shows the gap between first and second when you really need a way to show how fragmented the rest of the parties are, but it's at least a somewhat useful indicator.

(This is semantics either way because it only matters what the margin is across the entire region not the individual districts of course, but then what's the point of a breakdown map).

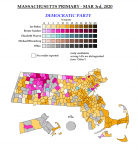

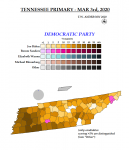

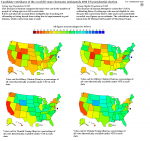

Of course, as Alex says the only really comprehensive way to do it is separate popular vote maps for each party, but that comes with its own can of worms like whether you use the same colour for everyone or not.

I actually got into making election maps because the Dave Leip US site only showed popular vote based maps for most elections, and those are so misleading I decided to start making majority-margin ones from scratch for everything.