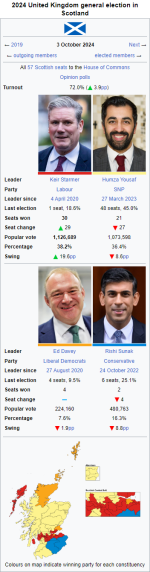

The 2022 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday 28 April 2022 to elect all 707 members of the House of Commons. The election saw the Liberal Party of Great Britain return to power for the first time since 2008, with Sir Edward Davey becoming the first Liberal Prime Minister since Nicholas Clegg. The election signalled the end of three straight election victories for the Unionist & Conservative Party of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and saw Prime Minister Sir Graham Brady leave Downing Street after fourteen years.

Opinion polling before the election suggested the Liberals had a consistent yet small lead over the Unionists but there was a lack of certainty over which party would emerge with more seats and therefore have, by convention, the ability to try and form a minority administration if neither major party won the 354 seats needed for an overall majority. The memories of the 2017 election, where the Liberals had led in the opinion polls throughout the campaign but fell way short of the Unionists on polling day, continued to play on the mind of both parties as well as the political commentariat and the pollsters, who had adapted their methodology accordingly.

The election campaign focused primarily around the slowing British economy, which risked dipping into recession if predictions from experts were to be believed, as well as Britain's military involvement in Rhodesia and its ongoing relationship with the European Community. The latter issue grew in importance throughout the campaign after Davey pledged that a future Liberal government would seek a bespoke trade deal and closer alignment to Europe, whilst Brady and the Unionists decried the Opposition's "surrender to the continent". The Government instead continued to adopt a continued independent trade policy and a 'transatlantacist' geopolitical outlook, including closer relations with Canada, the United States and the Commonwealth.

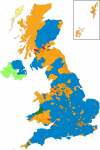

The Liberals would go on to win 371 seats, a majority of thirty-five, their largest majority since the 1996 election. The election saw continued demographic trends towards both major parties, with the Liberals winning large majorities in urban areas, Greater London and the 'Celtic Fringe' in rural Scotland and Wales. The Unionists meanwhile saw their dominance over southern and rural England expand despite the overall defeat. This election marked the first time, for example, that the Liberals won a majority in the House of Commons without winning any seats in rural Devon, Dorset or Somerset. The UK's third party, the Social Democratic and Labour Party, also made gains, especially in London where the party saw its strength grow from one seat to five seats. With Rushanara Ali taking charge of the Social Democrats, the election marked the first time that a major political party was led by a female leader, as well as the first time that a major party was led by an ethnic minority leader. Its haul of 24 seats was its best return since the 2005 election.

Elsewhere, the SNP held onto their sole seat of the Western Isles with a reduced majority, but failed to make in-roads anywhere else as most of their limited voter base instead opted for the Liberals, whilst Plaid Cymru suffered a similar fate, holding on to Cardiganshire but failing to win any of their other target seats in western Wales. The Irish Labour Party held onto its one seat in Belfast East, whilst eight Irish Nationalist MPs were elected but, as ever, refused to take their seats in the Commons.

Opinion polling before the election suggested the Liberals had a consistent yet small lead over the Unionists but there was a lack of certainty over which party would emerge with more seats and therefore have, by convention, the ability to try and form a minority administration if neither major party won the 354 seats needed for an overall majority. The memories of the 2017 election, where the Liberals had led in the opinion polls throughout the campaign but fell way short of the Unionists on polling day, continued to play on the mind of both parties as well as the political commentariat and the pollsters, who had adapted their methodology accordingly.

The election campaign focused primarily around the slowing British economy, which risked dipping into recession if predictions from experts were to be believed, as well as Britain's military involvement in Rhodesia and its ongoing relationship with the European Community. The latter issue grew in importance throughout the campaign after Davey pledged that a future Liberal government would seek a bespoke trade deal and closer alignment to Europe, whilst Brady and the Unionists decried the Opposition's "surrender to the continent". The Government instead continued to adopt a continued independent trade policy and a 'transatlantacist' geopolitical outlook, including closer relations with Canada, the United States and the Commonwealth.

The Liberals would go on to win 371 seats, a majority of thirty-five, their largest majority since the 1996 election. The election saw continued demographic trends towards both major parties, with the Liberals winning large majorities in urban areas, Greater London and the 'Celtic Fringe' in rural Scotland and Wales. The Unionists meanwhile saw their dominance over southern and rural England expand despite the overall defeat. This election marked the first time, for example, that the Liberals won a majority in the House of Commons without winning any seats in rural Devon, Dorset or Somerset. The UK's third party, the Social Democratic and Labour Party, also made gains, especially in London where the party saw its strength grow from one seat to five seats. With Rushanara Ali taking charge of the Social Democrats, the election marked the first time that a major political party was led by a female leader, as well as the first time that a major party was led by an ethnic minority leader. Its haul of 24 seats was its best return since the 2005 election.

Elsewhere, the SNP held onto their sole seat of the Western Isles with a reduced majority, but failed to make in-roads anywhere else as most of their limited voter base instead opted for the Liberals, whilst Plaid Cymru suffered a similar fate, holding on to Cardiganshire but failing to win any of their other target seats in western Wales. The Irish Labour Party held onto its one seat in Belfast East, whilst eight Irish Nationalist MPs were elected but, as ever, refused to take their seats in the Commons.