- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

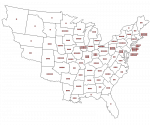

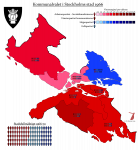

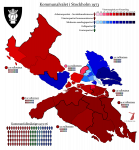

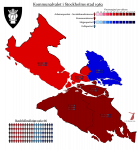

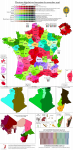

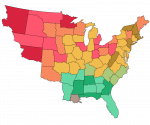

The Fourth Party System of the American Republic lasted from about 1880, when the ten-year period of gradual emancipation ended (a few "grandfathered" slaves continued to exist in the Deep Southern departments into the 20th century), until the rise of class-based parties in the 1900s and 1910s. The similarity between the party landscapes of the Third and Fourth systems (the only major change being the renaming of the Free Soil Party to the Radical Party) has led some political scientists to group the two together, but this is a minority view, and ignores the seismic shift in American society caused by the end of slavery. Treasurers Adams and Harrison attempted to secure the social and political rights of the freedmen, and while these efforts met with limited success generally, increased electoral scrutiny meant that Black Americans did gain, and avail themselves of, the right to vote to a great extent.

The Federalists remained the dominant party, as they had in all previous systems except the Second. Their strength was based primarily in the Northeast, whose major cities had developed patron-client networks that ensured immigrants and native-born workers stayed in the Federalist fold. The Radicals penetrated smaller industrial cities, but New York, Boston and Philadelphia sent majority-Federalist delegations to the National Assembly throughout the era. The farmers of the Midlands and Appalachia also continued voting Federalist, and with the urban machines and the old-line Yankees of New England created a three-part alliance that proved to contain a strong majority of the electorate.

The main opposition throughout the Fourth Party System were the Radicals. Ben Wade had transformed a broad-church, single-issue anti-slavery party into a coherent vehicle of the centre-left, and sent a few more conservative Free Soilers over to the Federalists in the process. But the new party also gained voters and talent from formerly unrepresented sections of American society. Chiefly, the Radicals would draw on the West for support - the Great Plains departments voted for them by large majorities in most elections, as did the industrial region around the Great Lakes. The Radicals were beginning to crack the Eastern cities by the turn of the 20th century, but it was only with the rise of Labor that the change really came.

Rural America, then, was the major battleground between the two parties. The Midlands, New England and Appalachia leaned Federalist, the Plains leaned Radical, and the upper Midwest, the Southwest and the rural Mid-Atlantic were swing regions. The need to win rural votes benefitted many of these regions, as agricultural subsidies, seed benefits, rural mail delivery and the National Railroad were all brought into place in the 1890s.

The South differed from the rest of the nation, as ever, because the Patriot Party still lingered there. Alexander Stephens had kept the party alive in his home region, and Wade Hampton and Ben Tillman continued the pattern. They dropped official support for the institution of slavery in the late 1880s, but remained committed to white supremacy throughout the era - as were most southern Federalists, for that matter. The "Cotton Belt" tended to be more inclined toward the Patriots and the Upper South toward the Federalists, but this was far from consistent and the entire region could swing from one party to the other based on individual candidates.

The Black population tended to vote Federalist, grudgingly, but because they were only the majority in a few Assembly divisions, their main source of influence was as a swing vote. The Radicals attempted to campaign in majority-Black districts in the 1890s and 1900s, but poor local organization meant they met limited success.

The electoral geography of the Republic saw its biggest shake-up ever in 1896, when Adlai Stevenson's "wedding-cake plan" of layered local government came into effect. Twenty provinces became 65 departments (and the city of New York, which was and is outside the system), and the entire legislative and electoral apparatus was reformed to fit the new borders. The size of the National Assembly (400) and the Electoral Assembly (250) were fixed at their current numbers, and single-member divisions for the former were drawn to be as equal in population as reasonably possible. Departmental general councils gave the Radicals and Patriots an institutional base, and the dual oversight of general council officials and prefect's offices extinguished many of the corrupt practices of the old provincial administrations. This seismic shift in how the Republic operated, along with the increasing class consciousness of workers and farmers, laid the foundations for the Fifth Party System, the most fractious in American history.

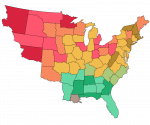

The Federalists remained the dominant party, as they had in all previous systems except the Second. Their strength was based primarily in the Northeast, whose major cities had developed patron-client networks that ensured immigrants and native-born workers stayed in the Federalist fold. The Radicals penetrated smaller industrial cities, but New York, Boston and Philadelphia sent majority-Federalist delegations to the National Assembly throughout the era. The farmers of the Midlands and Appalachia also continued voting Federalist, and with the urban machines and the old-line Yankees of New England created a three-part alliance that proved to contain a strong majority of the electorate.

The main opposition throughout the Fourth Party System were the Radicals. Ben Wade had transformed a broad-church, single-issue anti-slavery party into a coherent vehicle of the centre-left, and sent a few more conservative Free Soilers over to the Federalists in the process. But the new party also gained voters and talent from formerly unrepresented sections of American society. Chiefly, the Radicals would draw on the West for support - the Great Plains departments voted for them by large majorities in most elections, as did the industrial region around the Great Lakes. The Radicals were beginning to crack the Eastern cities by the turn of the 20th century, but it was only with the rise of Labor that the change really came.

Rural America, then, was the major battleground between the two parties. The Midlands, New England and Appalachia leaned Federalist, the Plains leaned Radical, and the upper Midwest, the Southwest and the rural Mid-Atlantic were swing regions. The need to win rural votes benefitted many of these regions, as agricultural subsidies, seed benefits, rural mail delivery and the National Railroad were all brought into place in the 1890s.

The South differed from the rest of the nation, as ever, because the Patriot Party still lingered there. Alexander Stephens had kept the party alive in his home region, and Wade Hampton and Ben Tillman continued the pattern. They dropped official support for the institution of slavery in the late 1880s, but remained committed to white supremacy throughout the era - as were most southern Federalists, for that matter. The "Cotton Belt" tended to be more inclined toward the Patriots and the Upper South toward the Federalists, but this was far from consistent and the entire region could swing from one party to the other based on individual candidates.

The Black population tended to vote Federalist, grudgingly, but because they were only the majority in a few Assembly divisions, their main source of influence was as a swing vote. The Radicals attempted to campaign in majority-Black districts in the 1890s and 1900s, but poor local organization meant they met limited success.

The electoral geography of the Republic saw its biggest shake-up ever in 1896, when Adlai Stevenson's "wedding-cake plan" of layered local government came into effect. Twenty provinces became 65 departments (and the city of New York, which was and is outside the system), and the entire legislative and electoral apparatus was reformed to fit the new borders. The size of the National Assembly (400) and the Electoral Assembly (250) were fixed at their current numbers, and single-member divisions for the former were drawn to be as equal in population as reasonably possible. Departmental general councils gave the Radicals and Patriots an institutional base, and the dual oversight of general council officials and prefect's offices extinguished many of the corrupt practices of the old provincial administrations. This seismic shift in how the Republic operated, along with the increasing class consciousness of workers and farmers, laid the foundations for the Fifth Party System, the most fractious in American history.

Last edited: