- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

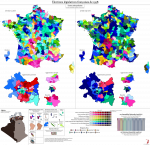

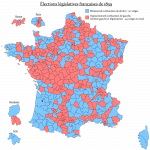

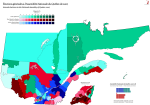

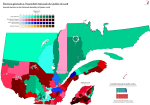

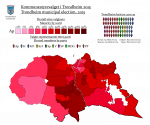

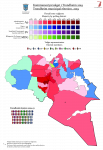

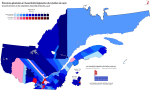

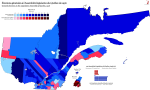

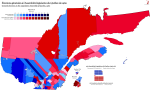

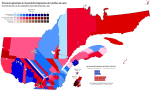

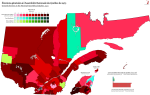

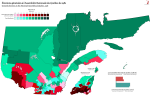

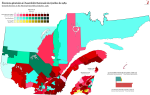

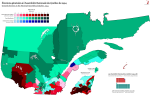

So this is the final legislative election of the Fourth Republic, and the legislature that sat when it all went down in Algiers in May 1958 and de Gaulle executed his coup d'état was called upon to assume the reins of power in a legal and orderly fashion. The narrative really breaks down in light of the RPF having entered the scene with a bang and become the largest party in 1951, then collapsed in 1956, only for de Gaulle to come back and seize power in 1958. If these two elections had come in the opposite order, it would've made so much more sense.

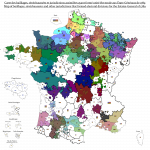

Note also the breakdown of the apparentement system with the Third Force no longer being a thing - nearly all of the successful apparentements in this election were centre-right, with only two (Ariège and Corsica) being centre-left. Also, Algeria took the logical next step from blatantly rigging its elections and just didn't hold any at all.

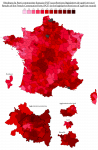

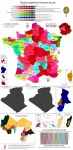

France 1956

The only Fourth Republic election left now, between @Nanwe and myself, is July 1946. I don't think I'm going to do that one straight away though, because I have a half-finished 1958 map lying around that I now have the data needed to finish. Suffice it to say the contrast with this one is stark.

Note also the breakdown of the apparentement system with the Third Force no longer being a thing - nearly all of the successful apparentements in this election were centre-right, with only two (Ariège and Corsica) being centre-left. Also, Algeria took the logical next step from blatantly rigging its elections and just didn't hold any at all.

France 1956

The only Fourth Republic election left now, between @Nanwe and myself, is July 1946. I don't think I'm going to do that one straight away though, because I have a half-finished 1958 map lying around that I now have the data needed to finish. Suffice it to say the contrast with this one is stark.