1982 – Italy

Host selection and background

1982, despite the expanded tournament, marked a return to some normalcy, as Italy became the second country to host the tournament twice. In contrast to the widespread allegations of corruption that had soured the mood around Iran’s hosting, Italy had won largely unopposed after Greece and Turkey had withdrawn their somewhat long shot bids. Similarly to Spain eight years earlier, the Italians had a select group of stadiums ready (with some widespread refurbishments planned) as well as the construction of a new 35,000 capacity stadium in Bari.

Despite the agreed list of host cities, Italy’s often chaotic political system and the general years of militancy in the 1970s as far-left and far-right clashed with each other (with the latter often supported by members of what was termed the “deep state” opposed to any Communist involvement in government) hampered the stadium projects, with a notorious example being the failed bombing attempt on the renovations of Bologna’s stadium by a fringe neo-fascist organisation. Following a long series of negotiations, a change in electoral law to a mixed-majoritarian system enabled greater stability within Italian politics, allowing Mauro Ferri’s Socialist government, elected in 1976, and returned again in 1980 to see the projects through.

Away from the political arena, there were also concerns, particularly in the south, that the stadium renovation projects would suffer some Mafia influence, and while never conclusively proven, there were rumours that the construction of the new San Nicola stadium in Bari was overbudget due to Mafia payments. The renovation projects, were nevertheless broadly successful, and by then time of the finals Italy was ready, though the total cost greatly exceeded the original budgets, seemingly par for the course of Italian infrastructure projects. Part of the reason for the cost increase was the need for more host cities and venues than previously, as the tournament expanded to twenty-four teams from sixteen, as had been promised by Carlos Dittborn upon his ascension to the Presidency in 1974 (as part of the compromise which saw him succeed Stanley Rous.)

The tournament also took place during a period of increased hooliganism and disorder within the sport across Europe, as sporting infrastructure designed for a different era began to buckle under violence and increased strain. While initially viewed as a British problem, there was growing recognition that it was becoming an increasingly pan-European issue, with a notorious incident at the second leg of the 1979 Federation Cup final between Borussia Mönchengladbach and Red Star Belgrade where seventeen fans from both sides and hundreds of others were injured in clashes with each other and the German police. This and a general trend for disorder in both domestic and continental matches, saw an increased cooperation between police forces across the continent, and saw Italy recruit extra police for the finals itself.

1982, also saw a new format, following complaints about the sterility of the second group stage in 1978, with a round of sixteen after the group stages (composed of each group winner, runner-up and four best third placed teams) to bring back some form of knockout jeopardy. Similarly to Spain in 1974, the groups were split between the twelve venues geographically, so as to ensure limited travel and reduce the risk of hooliganism. The commercial partnerships that had become an increasing hallmark of the tournament post-1970 were also increased as virtually every consumer sector found itself represented in some form, with car manufacturers, alcohol, fashion and luxury goods, soft-drinks and consumer electronics well represented across the board in a tournament of glorious technicolour.

Qualification

Italy and Argentina qualified automatically, leaving twenty-two slots to be decided. As part of the expansion, Africa and Asia-Pacific gained two additional spots to get three each, Europe had twelve, while North and South America had two automatic slots each (with the final slot to be decided via a playoff between the third-best North American side and the worst finishing South American group winner.)

In Europe, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and the Soviets all returned after a long absence. England, under the management of former Leeds United and Birmingham City manager Don Revie (who had previously been an England assistant in the 1960s) returned after missing out on 1978, with former manager Bill Nicholson (as FA Director of Coaching) part of Revie’s staff. Scotland also qualified, giving the finals a British tinge.

[1] Belgium and Yugoslavia also returned to the finals after missing previous tournaments, giving the European qualifiers a somewhat familiar feel. Belgium’s qualification came at the expense of the Dutch, who despite the emergency return of Hendrik Cruijff

[2] failed to fire and found themselves dumped out of qualifying some eight years after winning the world cup.

In the Americas, Brazil and Chile qualified comfortably (maintaining Brazil’s proud record of having never failed to qualify for the finals) while Peru saw off the challenge of Uruguay to secure the playoff spot against North America’s third best side, condemning the Uruguayans to a third straight failure to make the finals. While South America, failed to spring many surprises (with Uruguay having struggled for most of the 1970s), in the North, Honduras, Canada and El Salvador made Mexico’s usually serene path to the finals trickier than usual, with the Hondurans topping the group to win the North American Championship and qualify for the first time. Mexico’s final round victory over El Salvador saw them snatch the second spot, condemning El Salvador to the playoff with Peru which they would lose heavily.

It was Africa and the Asia-Pacific where the expansion of spots, saw some surprises as South Africa were joined by Cameroon and Algeria, two sides who had begin to make their mark on the Africa Cup, and the continent’s club competitions. Cameroon, like many postcolonial African states, a federal republic largely built around linguistic and ethnic divisions, had a number of players in former colonial power France, as did Algeria who had begin to challenge the traditional North African powers of Morocco and Egypt. In contrast to previous final rounds in Africa, which had gone down to the wire, the three sides qualified comfortably, though South Africa’s final qualifier away in Angola had to be moved to neutral Botswana due to the rapidly deteriorating security situation in the country, as the civil war gained pace.

[3]

In Asia, the political situation in Iran

[4] precluded their involvement, while the Iranian regime’s wish to re-establish their previous strategic hegemony saw relations with both Iraq and the U.E.E.A decline. As a result of Iran’s absence, the Middle Eastern half of the draw was more open than in recent years, allowing Kuwait (who had long been backed with the Emirate’s financial clout) to make the final round, where they alongside Korea, topped their group to qualify for the first time. The final Asia-Pacific slot, was taken by New Zealand, who surprised Australia and the Republic of China to make the final qualifying playoff (held in Singapore) where they held on to defeat Saudi Arabia 2-1 to make the finals for the first time.

[5]

Participating nations

- Italy (hosts)

- Argentina (holders)

- Algeria (debut)

- Belgium

- Brazil

- Cameroon (debut)

- Chile

- Czechoslovakia

- England

- France

- Germany

- Honduras (debut)

- Hungary

- Korea

- Kuwait (debut)

- Mexico

- New Zealand (debut)

- Peru

- Poland

- Scotland

- South Africa

- Soviet Union

- Spain

- Yugoslavia

The draw, held in Rome on 16 January 1982, saw a new seeding system introduced, with the number of seeds reduced from eight (as had been the case for every tournament from 1954 onwards) to six with one seeded team per group. Italy as hosts, and Argentina as holders were seeded automatically, leaving three of the slots to be filled the 1978 runners-up and bronze medallists. The final two slots, were taken by Germany and Poland, though it was assumed that if the Dutch had qualified, they as the most recent European World Cup winners would’ve been seeded in place of the Poles. The draw was as follows:

Group A Italy, Spain, Honduras, Peru

Group B France, England, Mexico, Hungary

Group C Brazil, Yugoslavia, Scotland, New Zealand

Group D Germany, Czechoslovakia, Korea, Algeria

Group E Argentina, Belgium, South Africa, Kuwait

Group F Poland, Soviet Union, Chile, Cameroon

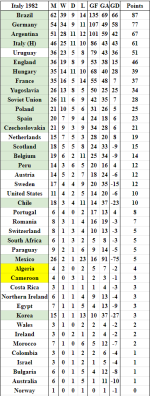

Tournament summary

Group A

Group A, hosted in Rome and Florence, paired hosts Italy with Spain, debutantes Honduras and Peru. The Italians, now coached by Enzo Bearzot who had spent the bulk of his coaching career within the Italian FA, had refreshed their side, but had suffered from the revelation of a match-fixing scandal in Serie A and Serie B, which had seen Milan relegated and several players, including Paolo Rosi banned (though most of the player sentences were reduced on appeal), which had seen Italy enter the tournament under a cloud. Spain, who had reached the quarter-finals as hosts in 1974, were a competitive side, built around a robust defence, were coached by former Uruguayan international José Santamaría, who had been a member of the 1954 championship winning side. Peru, were an aging team, but one which still had flashes of brilliance, while debutantes Honduras were largely regarded as minnows.

The opening game, between Italy and Spain, was a deathly dull 0-0 as Italy’s defence smothered Spain’s attackers, though the Spanish were perhaps unlucky to see Miguel Alonso’s goal bound effort diverted behind by the heel of Gaetano Scirea. The result, which saw widespread booing, and negative press coverage would see the beginning of Italy’s media blackout as the squad retreated from the limelight so as to combat the negativity. In the other game, held in Florence, and watched by FIFA Vice-President Artemio Franchi (a Fiorentina fan and the Italian FA President), Peru saw off a spirited Honduras thanks to a late goal from substitute Teófilo Cubillas, who rode two challenges before firing past Julio César Arzú, to secure Peru’s first win since 1970.

In the second round of fixtures, Italy, still not quite firing, despite the packed out Stadio Liberazione

[6], managed to cling on to a less than impressive 1-0 victory against the Peruvians, with Alessandro Altobelli’s late winner sealing the victory. Peru, playing a more defensive style than in the 1970s had become a hard team to beat, but a more adventurous Italian side should’ve been able to ease past their aging defence. In Florence, Spain eased to a 2-1 victory over Honduras, recovering from the shock of Héctor Zelaya’s opening goal for the Hondurans, taking advantage of a Luis Arconada mistake at a corner to tap home to score Honduras’s first ever World Cup goal.

In the final round of games, Italy finally spluttered into life, a Paolo Rossi brace, and goals from Daniele Massaro, Francesco Graziani and Giancarlo Antognoni easing them to a 5-1 win over a depleted Honduras, who due to a stomach bug which had swept their camp

[7] were denied a full-strength team, though their key-man Gilberto Yearwood (who based in Spain, was their only overseas international) was able to net a late consolation. Spain and Peru, played out an entertaining 2-2 draw as Peru’s veterans Percy Rojas and Teófilo Cubillas cancelled out Roberto López Ufarte’s double.

[8] The result saw Spain and Italy qualify automatically for the second round, with Peru’s qualification dependent on results in other groups.

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Italy | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 1 | +5 | 5 |

2 | Spain | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | +1 | 4 |

3 | Peru | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

4 | Honduras | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 8 | -7 | 0 |

Results

13 June Italy 0-0 Spain

14 June Peru 1-0 Honduras

18 June Italy 1-0 Peru

19 June Spain 2-1 Honduras

22 June Honduras 1-5 Italy

22 June Spain 2-2 Peru

Group B

Group B was split between Naples and Bari, and paired France, who had finished third in 1978, with England who were returning to the finals after failing to qualify in 1978, Hungary themselves returning to the finals for the first time in twelve years, and Mexico.

England, coached by former Leeds United and Birmingham City manager Don Revie (who had also worked as a part-time assistant at the 1962 and 1966 tournaments with the FA) had improved since their late 1970s nadir, but were in dreadful form going into the tournament, despite winning the 1981-82 Home Nations Championship. France, who had impressed with their technical attacking style in 1978 had a superb side, while Hungary had rebuilt and were again competitive having easily finished ahead of the English during qualifying. Only Mexico, perennial whipping boys, were viewed as not offering much.

The opening match, played in the baking evening heat of Naples, saw the French and English play out a 1-1 draw, as Revie’s decision to play a five-man midfield to counter France’s technical excellence largely worked, though it made for a stultifying spectacle, though the introduction of the gifted Spurs playmaker Glenn Hoddle, as a second-half substitute added a depth of technical quality to the English midfield, which with the exception of Ray Wilkins, was deeply workmanlike. Revie’s decision to stick with Ray Clemence was also vindicated as the veteran goalkeeper twice saved from Michel Platini to preserve the point. The other match, played in Bari’s new stadium (a glorious architectural achievement, but one that works due to it’s limited capacity) saw Hungary add further to Mexico’s miserable world cup record, as a hat-trick from substitute László Kiss, alongside goals from captain Tibor Nyilasi, Gábor Pölöskei and Sándor Müller saw the Hungarians crush Mexico 6-1, with the Mexicans unable to deal with Hungary’s physicality, continuing Mexico’s dreadful record at the finals.

The second round of matches saw England ease to a 2-0 win over Mexico, as the English struggled to find much fluidity in the summer heat. Mexico, improved from their shellacking at the hands of Hungary, were a limited threat though Hugo Sánchez, their key player (and one world-class performer) operated on a different wavelength and caused issues for England’s defence, though the decision of Revie to have Viv Anderson curb his natural attacking game and instead man-mark Sánchez reduced his influence over the course of the match.

[9] Revie’s decision to deploy Hoddle from the start, also allowed England’s midfield to gradually get a hold of the game, and if it hadn’t been for a superb display by José Pilar Reyes in the Mexican goal (including a brilliant point blank reaction to deny Kevin Keegan) the score probably would have been more. France and Hungary played out a 1-1 draw in Naples, with Hungary’s Gábor Pölöskei, cancelling out Gérard Soler’s opener. The game, while not a classic, did see one moment of incredible quality, as Internazionale’s Michel Platini, skipped past two challenges before delicately chipping a pass into the path of Dider Six, who’s shot was saved by Hungarian goalkeeper Ferenc Mészáros.

The final round of games saw England defeat Hungary 2-1, with Trevor Francis, Britain’s first one-million-pound player, scoring a brace after László Fazekas’s surprise opener. Despite the victory, England were more pedestrian than brilliant, though the ability to ground out results was something they’d lost in the post-Nicholson era. Nevertheless, the game was memorable, from an English perspective at least, for an excellent assist from Ray Wilkins, who’s perfectly weighted lob caught out the Hungarian offside trap and allowed Francis to fire home. In the other game, France eased to a 3-0 victory over Mexico whose poor record at the finals continued.

[10] The result saw France and England through as the top two teams in the group, with Hungary waiting to see if their results were enough to secure qualification to the next-stage for the first time since 1966.

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | England | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | +3 | 5 |

2 | France | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2 | +3 | 4 |

3 | Hungary | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 4 | +4 | 3 |

4 | Mexico | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 11 | -10 | 0 |

Results

16 June France 1-1 England

17 June Hungary 6-1 Mexico

20 June England 2-0 Mexico

21 June France 1-1 Hungary

25 June England 2-1 Hungary

25 June Mexico 0-3 France

Group C

The third group, played in Turin and Genoa, paired two-times champions Brazil, with the technically excellent, but often inconsistent Yugoslavia, Scotland and debutantes New Zealand. Brazil, had changed style from 1978, appointing Telê Santana, who had won a series of league titles in the 1970s with a technical, passing style of style play – Brazil’s highly technical midfield flourished in the 1979 South American Championship, winning the trophy for the first time in thirty years, raising hopes that after two tournaments of highly mechanised football, Brazil might be champions. Yugoslavia, who had had an inconsistent decade in the 1970s had a strong side, coached by Miljan Miljanić, who had led the side in 1974.

[11] Scotland, under the stewardship of former Celtic manager Jock Stein, were a solid side with more creativity than some of their previous squads, while New Zealand, coached by former Yugoslav assistant Milan Ribar, were a competitive if somewhat limited side.

[12]

In the opening round of fixtures, Brazil and Yugoslavia played out a game of technical excellence, with the Brazilians eventually triumphing 2-1, thanks to two late goals, the second of which from captain Sócrates Brasileiro, was a superb goal, drifting in-field and volleying the ball beyond the reach of Ratko Svilar. Despite the victory, Yugoslavia played well, with Safet Sušić shading the creative midfield battle, setting up their opener in the first half for Velimir Zajec to head home. Despite the quality on display, the game was also notable for an injury suffered by Paulo Roberto Falcão, which left Brazil with an unbalanced midfield. Scotland and New Zealand, grouped together in Genoa, played out a thriller, which while lower on quality, did not lack for entertainment, as Scotland nearly threw away a two-goal cushion to eventually win 3-2. The game, played at a fast pace saw Kiwi teenager Wynton Rufer nearly seal immortality only for Alan Rough in the Scottish goal to deflect the ball clear.

The second round of matches saw Brazil take the Scots apart 4-1, with their fluid midfield proving too much for the Scots to handle in the second half, though Scotland had taken a surprise lead through veteran Kenny Dalglish. Brazil’s second goal, which saw Éder Aleixo dink home following a move that saw seventeen completed passes was later voted goal of the tournament, and with Scotland flagging in the face of the yellow wave, two late goals settled the tie decisively in Brazil’s favour. In Genoa, Yugoslavia eased to a 2-1 victory over New Zealand, who were perhaps unfortunate to have a penalty claim for handball turned down, while Yugoslavia’s goal came from an arguably offside position, a recurring issue for smaller nations at the finals.

[13]

In the final round, Brazil scoring twice in either half, blew the New Zealanders away with a display of attacking virtuosity, as Sócrates Brasileiro scored twice and set up the other two (including one for Brazil’s much maligned battering-ram forward Sérgio Bernardino) to see the Brazilians ease into the second round with a perfect record, averaging just over three goals a game. In Turin, Scotland and Yugoslavia played out a see-saw 2-2 draw, with Ivan Gudelj’s seemingly late winner cancelled out by Graeme Souness to see the two sides finish level on points.

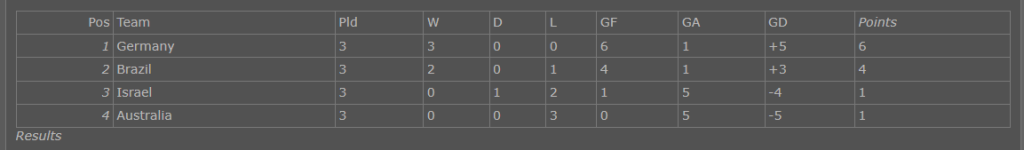

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Brazil | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2 | +8 | 6 |

2 | Yugoslavia | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

3 | Scotland | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 | -2 | 3 |

4 | New Zealand | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 9 | -6 | 0 |

Results

14 June Brazil 2-1 Yugoslavia

15 June Scotland 3-2 New Zealand

18 June Scotland 1-4 Brazil

19 June New Zealand 1-2 Yugoslavia

23 June Scotland 2-2 Yugoslavia

23 June Brazil 4-0 New Zealand

Group D

Group D, split between Milan and Bologna, was contested by Germany, Czechoslovakia who were returning to the finals after a lengthy absence, debutantes Algeria and Korea. Germany, under the management of Udo Lattek, who had enjoyed great success at club level were European champions, having triumphed over Czechoslovakia in 1980, while the Czechoslovaks, were hoping to convert their strong record at continental level onto the world stage. Korea, who had become the first Asian side to win a game at the finals, four years prior were a competitive side, while Algeria, had a strong core of European-based players (predominantly based in former colonial power France, as Algeria took advantage of FIFA’s rule changes on eligibility and were in strong form going into the finals, having finished third at the 1982 Africa Cup and warming up with a series of draws against Eastern European opposition.

The opening round of games saw Algeria pull off a surprise, holding onto a late lead, despite taking a battering, to cling on to a famous victory over the Germans. Algeria’s winner came from a piece of inspiration from Rabah Madjer, who on as a substitute, flicked the ball over the head of Hans-Pieter Briegel before dinking the ball into the path of Abdelmajid Bourebbou, who volleyed past the prone Harald Schumacher. The result, at a time of increasing economic problems, due to a botched liberalisation effort, saw widespread joy erupt in Algiers. In the other match, Czechoslovakia eased to a 2-0 victory over Korea, with Tomáš Kříž scoring both goals, in a game where poaching instinct made up for the general lack of chances.

In the second round of games, Germany recovered from their shock defeat to beat Korea 4-1, aided by an error-strewn performance from the usually reliable Cho Byung-deuk in goal, who gifted two goals due to handling errors and gave away a penalty after upending Horst Hrubesch. The game, despite the scoreline, is infamous for a racist gesture from the German bench to Korean star man Cha Bum-kun (who himself played in Germany) resulting in widespread condemnation within Germany, if little censure from FIFA itself. Algeria, meanwhile, were brought down to earth by Czechoslovakia who won 3-1, thanks to a superb midfield performance from captain Antonín Panenka, who dictated the play from a deep lying role, setting up all three Czechoslovak goals with deft passing play. Although able to claw a consolation back through Paris FC’s Mustapha Dahleb, the Algerians looked spent after their efforts against Germany.

In the final round of fixtures, Algeria beat Korea 1-0, thanks to a goal from Lakhdar Belloumi, who powered a header home from Dahleb’s corner, though Korea were aggrieved that their late equaliser was ruled out for a less than obvious foul on Noureddine Kourichi in the build-up. Germany, who had struggled in their opening game, before improving somewhat against Korea, won 2-0 against a surprisingly subpar Czechoslovakia, who rested several players, perhaps with an eye on the second round. The result, ensured that all three European teams finished on four points, a genuine rarity.

[14]

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Germany | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 3 | +4 | 4 |

2 | Czechoslovakia | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 3 | +2 | 4 |

3 | Algeria | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

4 | Korea | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 7 | -6 | 0 |

Results

16 June Germany 1-2 Algeria

17 June Czechoslovakia 2-0 Korea

20 June Germany 4-1 Korea

21 June Algeria 1-3 Czechoslovakia

24 June Czechoslovakia 0-2 Germany

24 June Korea 0-1 Algeria

Group E

Group E paired holders Argentina with a Belgian side blessed with a superb generation, South Africa and Middle Eastern debutantes Kuwait, who had taken advantage of Iran’s absence (as well as very generous state funding) to qualify. Argentina, now coached by 1978 assistant César Luis Menotti, had refreshed their squad with Diego Maradona, the star man of the 1979 World Youth Cup, becoming a key player.

[15] Belgium, returning to the finals after a long absence, had a superb squad, finishing runners-up in the 1980 European Nations Cup and comfortably knocking out their neighbours (and 1974 champions) the Netherlands in qualifying for Italia ’82. South Africa, retained a strong core, with veteran Colin Viljoen still captaining the side, which contained several British-based players. Kuwait were the main unknowns, though they had established a coaching setup with strong ties to Europe, thanks to increasing sporting ties between the Middle Eastern monarchies and their European allies.

In the opening round of games, Belgium held on to a 1-0 win over Argentina, thanks to a thunderbolt from West Ham United winger François Van der Elst, who had come on as a substitute. Despite their array of talent, the Argentines found it hard to break down Belgium’s 3-5-2 formation, with Maradona in particular growing increasingly frustrated at Argentina’s lack of cutting edge. In the other game, South Africa beat Kuwait 2-1, thanks to goals from Nelson Dlada and Brian Stein after Faisal Al-Dakhil gave Kuwait an early lead in Verona. The game, is memorable for two moments of racist abuse, directed at players from both sides, as monkey chants provided the backdrop, giving an indication of the growing militarisation of terraces across Europe, as radical and criminal movements began to establish firmer ties within fan groups.

The second round of games saw Argentina improve to beat South Africa 3-0 in Udine, as Maradona revelled in the space afforded him by South Africa’s high defensive line, to score the opener and set up the second for Mario Kempes, before substitute Jorge Valdano bundled the third home from a corner, despite protests from Gary Bailey that he was fouled in the build-up, following a clash in midair with Daniel Bertoni. In Verona, Belgium eased to a 2-0 win over Kuwait, with goals in either half from Alexandre Czerniatynski settling the game. The match, despite Belgium’s routine win, remains infamous in World Cup history for a half hour delay in the second half starting as the Kuwaiti team had to be persuaded out for the second half following an intense debate from the Kuwaiti FA head and the officials.

In the final round Argentina cruised to a 4-1 win over Kuwait, with goals from Daniel Passarella, Bertoni and a brace from Ramón Díaz seeing them through, as Kuwait wilted, despite a late consolation goal from Abdullah Al-Buloushi. Belgium and South Africa played out a 1-1 draw with Jomo Sono’s late equaliser rescuing a point for South Africa after Jan Ceulemans opener. Sono, who had become one of the star players in the American Soccer League, would in a twist of fate, move to Anderlecht following the tournament.

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Belgium | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | +3 | 5 |

2 | Argentina | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 | +5 | 4 |

3 | South Africa | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | -2 | 3 |

4 | Kuwait | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 | -6 | 0 |

Results

16 June Argentina 0-1 Belgium

17 June South Africa 2-1 Kuwait

20 June Argentina 3-0 South Africa

21 June Belgium 2-0 Kuwait

25 June Kuwait 1-4 Argentina

25 June Belgium 1-1 South Africa

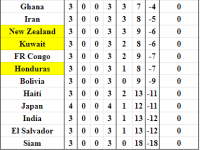

Group F

The final group, split between Sardinia and Sicily, paired Poland and the Soviets, at a time of increasing tensions within the Warsaw Bloc, with South American side Chile and African debutantes Cameroon, who similarly to Algeria had several players based in France.

Poland, who were enjoying a period of sustained international success, due to a superb generation of players, saw off the Soviet Union 2-1, thanks to goals from Włodzimierz Smolarek and Andrzej Buncol cancelling out Andriy Bal’s opener, giving the Poles a first win over the Soviets in nearly thirty years. The game, taking place during a period of increasing dissent within Poland towards the country’s communist regime

[16] saw Poles defying suppression of movement laws to celebrate the result. In the other match, Cameroon and Chile played out the dullest match of the round, as neither side could fashion much in the way of chances, with the game finishing 0-0.

In the second round of games, the Soviets improved to beat Chile 3-0, with Dynamo Kyiv’s Oleg Blokhin scoring a second half brace to the put the game beyond the reach of the South Americans, whose poor record at European tournaments continued. Cameroon, built around a strong defence, negated Poland’s attacking menace, with a display of defensive doggedness which would’ve made an Italian proud, with Michel Kaham man-marking the Zbigniew Boniek out of the game, with the Cameroonian efforts seeing them applauded off the pitch at the end, despite having had to face the usual chorus of monkey chants which greeted black players across Europe.

In the final round of games, the Soviets and Cameroon drew 1-1 with Albert Milla scoring a late equaliser to net Cameroon’s first ever goal at the finals, after the Soviets had taken the lead through Aleksandre Chivadze, after the usually unflappable Thomas N'Kono made a hash of a cross from Yuri Gavrilov and spilled the ball in Chivadze’s path. In the other match in Palermo, Poland eased to a 3-1 win over Chile, with Grzegorz Lato scoring a hat-trick after Carlos Caszely had opened the scoring for Chile against the run of play, with the result seeing Poland top the group.

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Poland | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | +3 | 5 |

2 | Soviet Union | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | +2 | 3 |

3 | Cameroon | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

4 | Chile | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | -5 | 1 |

Results

14 June Poland 2-1 Soviet Union

15 June Chile 0-0 Cameroon

18 June Soviet Union 3-0 Chile

19 June Cameroon 0-0 Poland

23 June Poland 3-1 Chile

23 June Soviet Union 1-1 Cameroon

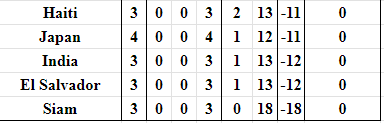

Ranking of third placed teams

| Group | Team | Played | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

| D | Algeria | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| B | Hungary | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 4 | +4 | 3 |

| A | Peru | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| F | Cameroon | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| B | Scotland | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 | -2 | 3 |

| E | South Africa | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | -2 | 3 |

The new format for the finals, which saw the four best third-place finishing teams from the group stage join the top two finishers in a straight knockout round of sixteen necessitated a new drawing system for the eight second round matches, which were drawn following the conclusion of the group stage on June 26 in Rome. The draw was as follows:

Match 1 – A1 vs. D3 – Italy vs. Algeria (Rome)

Match 2 – B2 vs. F2 – France vs. Soviet Union (Naples)

Match 3 – E1 vs. D2 – Belgium vs. Czechoslovakia (Bari)

Match 4 – C1 vs. B3 – Brazil vs. Hungary (Milan)

Match 5 – D1 vs. A3 – Germany vs. Peru (Genoa)

Match 6 – A2 vs. C2 – Spain vs. Yugoslavia (Turin)

Match 7 – F1 vs. E2 – Poland vs. Argentina (Verona)

Match 8 – B1 vs. F3 – England vs. Cameroon (Bologna)

Round of Sixteen

The opening match in Rome paired the hosts with surprise packages Algeria, who had pulled off the shock of the tournament with their victory over Germany in Milan in the first round. While many were hoping for lightning to strike twice, Italy who had somewhat flattered to deceive in the group stages, found their groove to ease to a 3-1 win, with Paolo Rossi scoring twice to settle any nerves after Salah Assad had equalised for Algeria against the run of play, after a rare error from Italian captain Dino Zoff. The victory, in front of a capacity crowd in Rome, saw the Italian squad break their media silence to celebrate the result.

In Naples, France, who had spluttered during the group stages, met the Soviets in a game hampered by Naples’s summer heat, despite the match kicking off in the evening. The game, played at a subdued pace appeared to be heading to a penalty shootout before Alain Giresse’s late strike settled the tie in the final minutes of extra-time. The game saw the Soviets left aggrieved by the decision not to award a goal to Khoren Oganesian after his shot appeared to cross the line before being cleared by Marius Trésor, with the referee adding further fuel to the Soviets anger by overruling his linesman.

[17]

In Bari, Belgium and Czechoslovakia played out a classic, with the game see-sawing as both sides took, lost and retook the lead, before Belgium eventually triumphed 3-2 thanks to a late winner from Ludo Coeck, who headed home from veteran Wilfried Van Moer’s floated freekick. The match, which saw a superb goal from winger Marián Masný, who burst through two tackles before burying the ball beyond the reach of Jean-Marie Pfaff in the Belgian goal. Belgium’s win saw them reach the knockout stages for the first time since 1930.

Brazil, who had been the best side to watch in the group stages, proved far too strong for Hungary, seeing off the former powers 4-0, thanks to two penalties as Hungary found themselves unable to deal with Brazil’s fluid midfield, with the Hungarians indebted to veteran goalkeeper Ferenc Mészáros for keeping the score down. Brazil’s victory, saw a superb goal from Tuzico, who drifting inside, flicked the ball over two Hungarian markers, exchanged a one-two pass with Antônio Cerezo before drilling the ball from the edge of the area out of the reach of Mészáros to add gloss to a superb performance.

In Genoa, Germany who had improved after being shocked by the Algerians in their opening match, eased to a 2-0 victory over Peru, with goals from Pierre Littbarski and the maverick Paul Breitner, a Marxist whose frequent comments on German politics and society drew the ire of the more conservative elements of the German press.

[18] The game, while a fairly routine German win, marked the end of several international careers for Peru, including Teófilo Cubillas, captain Héctor Chumpitaz and Percy Rojas, seeing the end of a generation which had brought a sustained period of success to the Andean nation.

Facing each other in Turin, Yugoslavia held on to a late goal in extra-time to knockout Spain from substitute Stjepan Deverić, who was making his debut in doing so. The game, while not a classic, had a degree of tension as both sides cancelled each other out in a display of mutual neuroticism.

[19] The game, which had seen Enrique Saura’s scuffed shot equalise for Spain after Vladimir Petrović had given the Yugoslavs the lead after a mix-up between Luis Arconada and Andoni Goikoetxea left an unguarded net. Yugoslavia’s winner, after the ball had ricocheted from a failed clearance summarised the quality on display.

Argentina and Poland, meeting in a re-run of 1974, saw the champions lose on penalties after a sterile game of mutual paranoia rendered any thoughts of a contest muted as Maradona, who had enjoyed a somewhat subpar tournament was marked out of the game by Polish captain Władysław Żmuda. The game, which saw few chances, went to penalties with Argentina’s decisive kick blazed over the bar by the usually reliable Passarella to send the champions out at the second round.

The final match, pairing England, who had been consistent if not spectacular in the group stages, with Cameroon who had qualified for the group stages with a rock-solid defence, was a classic, with England coming back from a surprise Cameroonian opener scored from Paul Bahoken to win 2-1 thanks to two goals from Bryan Robson, who’s box-to-box midfield performance won the tie, though a late save from Clemence ensured England won the tie, much to the joy of the watching England fans who were somewhat outnumbered by locals backing the underdogs from West Africa.

[20]

Results

28 June Italy 3-1 Algeria

28 June France 1-0 Soviet Union (a.e.t)

29 June Belgium 3-2 Czechoslovakia

29 June Brazil 4-0 Hungary

30 June Germany 2-0 Peru

30 June Spain 1-2 Yugoslavia (a.e.t)

1 July Poland 0-0 Argentina (Poland 4-2 Argentina on penalties)

1 July England 2-1 Cameroon

Quarter-finals

The quarter-finals paired hosts Italy with France, favourites Brazil with Belgium, Germany with Yugoslavia and Poland and England, in a round dominated by European sides.

The opening game between Italy and France was a classic, with the Italian defence pitted against France’s technically gifted midfield. Italian defender Claudio Gentile, a man-marker almost without peer was pitted against Michel Platini, and marked him out of the game by fair means or foul, in a display of defensive brilliance rarely seen on the world stage.

[21] Paolo Rossi, who had emerged as Italy’s main attacking threat opened the scoring through a cross from Antonio Cabrini, leaving Jean-Luc Ettori no chance. Italy’s second goal, from an error from Jean Tigana, seemed to put them in control, before two quick-fire goals from Didier Six restored parity. As the French grew increasingly into the game, Italy were indebted to Dino Zoff for a superb double save to keep the scores equal. With the match seemingly heading to extra-time, it was left to Paolo Rossi to fire home the winner after a poor clearance from the otherwise excellent Manuel Amoros to send Italy through and a deflated France home. In contrast to the thriller in Rome, Brazil eased to a 3-1 win over Belgium, with Brazil’s intricate midfield play too strong for the Belgians, with the game over as a contest by the hour mark thanks to three quick-fire Brazil goals, as the Belgians struggled to contain Brazil’s fluidity, as the Brazilians continued their generally brilliant recent record at the finals (having made the final twice in the 1970s.)

In Milan, Germany’s functionality saw them ease to a 1-0 win over the Yugoslavs, in a game marred by bad tempers and poor officiating as the German goalkeeper Harald Schumacher flattened Yugoslav substitute Predrag Pašić without punishment, requiring Pašić to be substituted himself some ten minutes after coming on. Yugoslavia, having a late equaliser ruled out for a foul on Schumacher by Vahid Halilhodžić added insult to injury, and led to claims of conspiracy in the Balkans, as the Germans marched on. In Naples, England’s tournament came to an end as their pedestrian midfield, shorn of Ray Wilkins due to injury and seeing Bryan Robson hobble off after half-an-hour following a pulled hamstring, struggled to create anything, despite Revie’s late introduction of Glenn Hoddle. Poland’s victory, inspired by Zbigniew Boniek who settled the tie with a deft chip over Ray Clemence, brought Revie’s reign as England manager to a sad end.

[22]

Results

4 July Italy 3-2 France

4 July Belgium 1-3 Brazil

5 July Germany 1-0 Yugoslavia (ae.t)

5 July Poland 1-0 England

Semi finals

The semi-finals paired Italy with Brazil and Germany with Poland, with the Italians facing Brazil in Naples, and Germany and Poland hosted in Turin. The first semi-final was a classic, with Brazil triumphing thanks to a late winner from Éder Aleixo to win the tie 4-3 as Italy, perhaps uncharacteristically, played a gung-ho style, in an attempt to counter Brazil’s midfield excellence. The game, which saw a second consecutive hat-trick from Paolo Rossi, who would sadly never quite hit the same heights internationally again, appeared to be heading Italy’s way before Sócrates Brasileiro, Brazil’s captain and a player of extraordinary brilliance, played a perfectly weighted cross foe Aleixo to run onto, firing the ball past Dino Zoff to settle the tie and send Brazil into a second consecutive final.

In the other game, Germany’s functional style ground out a result, as their defence nullified the unpredictable Grzegorz Lato. Poland were further hampered by the absence of Boniek who had received a one game suspension after picking up a third yellow card in the quarter-final with England. As a result, Germany eased to a 2-0 win, with Klaus Fischer belying his age (but not his poaching ability) scoring both after coming on as a substitute for Bernd Schuster, who had been surprisingly underutilised during the finals.

[23]

The third place playoff saw Italy defeat Poland 2-0 to finish third, as a side which had played more joyfully than had been expected reconnected with their fanbase following the match fixing revelation of 1980.

Results

8 July Italy 3-4 Brazil (a.e.t.)

8 July Germany 2-0 Poland

Third-place playoff

10 July Italy 2-0 Poland

Final

The final, pitted the tournaments most eye catching side in Brazil, who’s free flowing football caught the global imagination with the side’s most consistent team, who had ground out result after result to make the final, shock defeat to Algeria notwithstanding.

The final, held in Rome and watched by a global record audience of some 1.3bn people, was the first to pit two former champions against each other, with the 1958 and 1970 victors facing the 1962 champions. Most people expected Brazil’s fluidity to seize the day, though Germany’s “tournament mentality”, which saw them consistently reach the final stages of international tournaments was not to be discounted.

The final, while not a classic was not light on drama, with the goalless first half seeing a number of chances and half chances. Lattek’s decision to start Bernd Schuster and Felix Magath in midfield, as a playmaking duumvirate and revert to a four-man defence, with Paul Breitner reverting to left-back ahead of Hans-Peter Briegel, had been met with surprise in Germany, with most commentators expecting the Brazilians to overpower Germany’s lighter midfield. In contrast, Germany’s greater mobility on the ball caused Brazil problems, as did the battering ram forward play of Klaus Fischer and Horst Hrubesch, with Brazil’s defence unable to cope, as Lattek had noted in their difficulties in dealing with Paolo Rossi in the semi-finals.

The match itself was largely over as a contest by the seventy-seventh minute, as Fischer, having given Luiz Carlos Ferreira, who had otherwise enjoyed an excellent tournament a torrid time, bullying him in the air and on the ground to score twice, though the second goal was aided by a mistake from Waldir Peres, who miskicked a clearance straight to Fischer who fired home. The second goal, is particularly famous in Germany for the appearance on television of President Annemarie Renger, the first woman to hold the position, wagging her finger at the TV cameras from the stands in a playful gesture. Despite a late flurry from Brazil, including a late goal from Carlos Renato, Germany held on, with Schuster scoring the third and final goal in the eighty-ninth minute to ensure German delirium.

How then should 1982 be remembered? Certainly compared to its immediate predecessor, it was a much better tournament, with three great sides in Brazil, France and the hosts, as well as several classic matches, and the joy of debutantes Algeria and Cameroon both making a case for African football in making the knockout stages. And yet this a tournament, where the winning side, a largely functional team with the ability to grind out results triumphed, though it should be said that in Udo Lattek they did have a superb coach and mentality to win, While blighted by monkey charting and intimidatory policing from the heavy-handed Italian state, the finals were more joyous than perhaps expected as the World Cup passed without major off-field incident.

Final

11 July Brazil 1-3 Germany

[1] Scotland were perhaps lucky to qualify, securing the point necessary with a blatantly handled goal against Israel in Tel Aviv.

[2] Cruijff, like his contemporary George Best, had a somewhat itinerant career after leaving Barcelona, spending a season in the ASL with the Los Angeles Aztecs, before moving to Dordrecht in the Netherlands, Levante in Spain and in a surprise move Second Division side Leicester City, where he faced off with George Best, who had swapped Fulham for Chelsea. With Allan Simonsen playing for Charlton the English second tier had a claim to having more Ballon D’Or winners than any other in Europe.

[3] South Africa’s own involvement, despite constant cadging from the Americans, was largely cosmetic, with South Africa supplying surplus weaponry to the Democratic Front which was backed by the US and Congolese governments in opposition to the Soviet aligned government which had emerged in the aftermath of the Portuguese withdrawal. Despite pressure, the South African government of Colin Eglin, which had won re-election in 1981, refused to allow the Washington backed rebels use of South-West Africa as a staging post, for fears of potential domestic spillover.

[4] Long simmering resentment against the Shah’s rule burst into the open in the tail end of 1978, and a period known as the Anarchy saw long suppressed groups, including Communists, Islamists and Secular Liberals vie for control. None of these, however, were as well organised as the army who after several months of parliamentary deadlock and failure to agree a new constitution, staged a coup and established a new junta which formed a Regency Council (essentially continuing the imperial state without the Shah.) While less autocratic, and ending some of the worst excesses of the later 1970s, the new junta were no less authoritarian in leanings than their predecessors.

[5] New Zealand’s qualification, alongside the national cricket team becoming competitive, managed to briefly unseat the national rugby side for press attention and oxygen, a feat only sporadically achieved since.

[6] Including Crown Prince Victor Emmanuel, a controversial figure within Italy, for his frequent pronouncements on politics and society.

[7] The Hondurans, due in part to cost, were one of the last sides to make it to Italy, and were staying in fairly basic accommodation with limited cooking facilities, upon which the bug was blamed.

[8] López Ufarte, was, in contrast to previous decades where the Spanish FA naturalised numerous foreign players for the national team, the only non-Spanish born member of the squad, having been born and raised in Morocco by Spanish parents. Despite overtures from the Moroccan FA, he declared for Spain, and made his debut in 1977.

[9] Anderson, becoming the third non-white English international and second black England international to feature at the World Cup after Paul Reaney in 1970, at a time of heightened racial tension in Britain was often viewed as a watershed, though in many ways it marked the growing recognition within British football that BAME players were an increasingly important part of the game in Britain. Outside of England, Scotland had taken Paul Wilson to the 1974 and 1978 finals.

[10] Mexico’s poor record at the finals would see the government support a programme to overhaul the country’s youth and senior football teams, resulting in the side becoming much more competitive on the global stage.

[11] Miljanić’s appointment in 1980 coincided with the death of former President and Supreme Leader Josip Broz Tito, who was succeeded as President by Edvard Kardelj – his first game, a friendly with the Soviet Union cementing the long-growing détente between the two former rivals, with Soviet General Secretary Yuri Andropov in attendance.

[12] Similarly to their Australian neighbours, the New Zealand side contained some players with overseas experience including former Brentford midfielder Brian Turner and Norwich City teenager Wynton Rufer, who would move to Switzerland following the tournament. The squad itself had a significant number of overseas-born (largely British) internationals. Billy McClure, who had become the first overseas international in Iran in 1977 was, alongside Rufer, the only member of the squad to play outside of Australasia, playing for Greek side PAOK Salonika.

[13] While FIFA’s technical reports had long shown that the quality of refereeing was genuinely high, the scale of inconsistent decisions often going in favour of more established nations, was becoming an increasing bugbear at FIFA’s various congresses.

[14] David Lacey, The Guardian’s main football correspondent, would describe the group as prosaic but one that remained compelling due to each team’s respective strengths and failings.

[15] Maradona, who had begun his career with Argentinos Juniors, was one of the rare beasts, who played for both River Plate and Boca Juniors, joining the former before their financial problems, saw him rejoin Argentinos who sold him after a season to Boca, thus circumventing selling him directly.

[16] The Eastern Bloc had seen a greater liberalisation in the 1970s, as the Soviets as part of a period of economic liberalisation and greater freedom (while still maintaining stricter party control) had largely allowed greater autonomy for the Warsaw Pact members, resulting in greater expressions of dissent within the Eastern European bloc. However, there were countermovement’s against this, with alarm in the Polish military and state security apparatuses at the growth of anti-regime movements which had coalesced into a broader front. With the Soviets declining to deploy troops, but covertly increasing troop build-up in the border regions, the Polish military assumed control of the party and government under the troika of Józef Użycki, Florian Siwicki and Wojciech Jaruzelski.

[17] Whilst no evidence of wrongdoing has ever been found, the referee Germany’s Adolf Prokop, was stood down from the next round.

[18] Breitner, who had begun his career with Bayern Munich, had a somewhat itinerant career, playing in Spain, Italy and France for various clubs, before returning to Bayern in the 1980s.

[19] Both Spain and Yugoslavia had well deserved reputations for being brittle, self-doubt often getting in the way of victory.

[20] England’s victory, coincided with a series of high-level European meetings hosted in Rome, with British PM Dennis Healey meeting the squad at their base in Emilia-Romagna during the tournament.

[21] For all the disquiet over Italy’s defensive game, their defence had supreme technical ability, with the Italian side broadly comfortable with using the ball, as opposed to the traditional view of a blood-and-thunder British centre-back.

[22] Revie, who had long wanted to return to club football, had agreed with the FA that he would step down after the conclusion of the tournament, with Bill Nicholson taking temporary charge until a permanent successor could be found.

[23] Schuster had suffered an injury in Germany’s final warm-up match with Austria, and while he was still selected for the tournament, he was largely used as an impact substitute by Udo Lattek until the knockout stages.