1990 – Soviet Union

Host selection & background

If 1986 had marked the first time FIFA had awarded hosting rights with a view to growing the game, as well as extensive commercial rights, 1990 marked a return to Europe with a new host nation, as the Executive Committee awarded the tournament to the Soviet Union unanimously following the withdrawals of England and Germany, presenting the U.S.S.R. with an easy victory over Greece’s quixotic bid. Similarly to the Americans, and in contrast to the Greeks, the Soviets had no need to build new stadiums or much in the way of sporting infrastructure, though the troika of Yuri Andropov, Nikolai Ryzhkov and Mikhail Gorbachev used the tournament as partial justification for their implementation of further economic reforms and infrastructure investment.

In contrast to the drawn-out process for awarding host city rights in the United States, four years prior, the Soviets largely chose on the basis of geographic convenience with European Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and the Caucasus chosen as host regions: host cities included Moscow, Leningrad, Rostov, Volgograd, Kiev, Odessa, Kharkiv, Minsk, Baku, Tbilisi and Yerevan. Vilnius had also been proposed as a venue, but increasingly nationalist tensions in the Baltics saw this overruled.

[1] While the Soviet leadership had largely concentrated on economic reforms, as relations between the two superpowers entered on of their thaw periods, increasing nationalist tensions in both the Baltic Republics and Armenia and Georgia had seen increased troop presence, particularly in the Southern Caucasus, as tensions in the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast threatened to spill over into both Armenia and Azerbaijan.

[2]

While no new stadiums were built, extensive renovations were ordered following one of the worst stadium disasters in recent memory, as a crush during a particularly icy evening at a Federation Cup game between Spartak Moscow and Rapid Vienna at the Central Lenin Stadium in 1984 saw some four hundred Spartak fans killed. In a decade noted for several horrendous near misses, the disaster would see the Soviet authorities extensively remodel their stadiums to remove some of the bottlenecks and general safety issues which had led to the crush. While nowhere near as capricious as the Argentine or Iranian authorities had been for tournaments with similarly authoritarian state regimes, the World Cup hosting committee was plagued by overspend, though due to the Andropov regime’s emphasis on anticorruption, any graft was largely covert.

If the United States marked a high point for the commercial arm of the tournament and FIFA itself, the 1990 tournament marked a retrenchment of sorts, as the Soviets were less predisposed to commercial sports sponsorship, though the country’s long transition to a form of market socialism

[3] had seen private enterprises gradually become more established within the country.

[4] Outside of these considerations, 1990 also marked the return of hosting rights to a traditional power of sorts, with Soviet club sides and the national side both enjoying several periods of success, with the Soviets managing to consistently reach the latter stages of both club and international competitions. The shift to decreasing the age for transfers from thirty to twenty-five also saw several players move overseas, including several from Dynamo Kyiv to clubs in Italy and Germany, which often saw an economic deal as part of the exchange, with a FIAT factory established in Kyiv as part of the deal taking Igor Belanov to Juventus.

[5] The Soviets, coached by former Zenit Leningrad manager Yury Morozov, were on a good run of form and had won their second continental trophy in 1988, defeating the much fancied Dutch to win their second European Nations Cup in Berlin, leading many to tip them as dark horses for the tournament. Despite the increasing instability in the further reaches of the Union, and the general creakiness pervading parts of the Eastern bloc, the tournament offered an unparalleled opportunity for communisms paramount state to promote both itself and its way of life to a global audience, as well as shore up its own increasingly consumer oriented domestic audience.

[6]

In contrast to four years prior, where American security had largely followed a laissez-faire model, the Soviets, wary of any potential hooligan issues or hostile media, were more restrictive on their visa programme, though following agreements struck with the participating European nations (due in part to European fans making up the bulk of international attendees as well as the broad reach of hooliganism in Europe) these were relaxed in exchange for strong police cooperation. As part of the relaxing of certain entry restrictions, the country also allowed widespread foreign media in, with both sports journalists and foreign affairs correspondents attending the tournament in large numbers.

[7]

1990 retained the same format as introduced in 1982, with six groups of four followed four knockout rounds, with groups split geographically, though similarly to the United States four years prior, the country’s vastness and hot summer temperatures, with games kicking off at times suitable for European television, causing issues for participating teams.

Qualification

The Soviets and holders Brazil qualified automatically leaving twenty-two places to be decided via qualification. While there were some surprises in qualification, 1990 marked the lowest number of debutantes at a tournament for several years, as several sides returned from the wilderness.

In Europe, the two major surprises were Belgium and France’s failure to qualify, particularly the French having been consistently excellent from 1978-1986 followed up failure to qualify for the 1988 European Nations Cup (thus being unable to defend their title) with a miserable qualification campaign which saw them knocked out of contention by Romania, who returned to the finals after a long absence. Elsewhere, the Dutch returned to the finals after twelve years, having failed to qualify twice in the 1980s, taking revenge on their Belgian neighbours in the process, while the Irish, managed by former England international Jimmy Armfield, returned to the finals for the first time since 1966 after finishing ahead of Sweden.

[8] Armfield, who counted former England teammate Jack Charlton and Ireland international Eoin Hand amongst his coaching staff, implemented a pressing style and scoured the Irish diaspora for players, with numerous British born players following in the footsteps of Ian Callaghan and Shay Brennan. Elsewhere in Europe, England, who had followed up their third-place finish in USA ’86 with a fourth-place finish at the 1988 European Championships, qualified with ease as did Scotland who looked to build on the success of their tournament four years prior. The Germans and Italians, perennial challengers for the tournament, also qualified comfortably alongside Spain, while both Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia returned to the finals after missing out on the tournament in the States.

In the Americas, Mexico failed to qualify for consecutive tournaments for the first time, after finishing third in the North American Championship and losing their playoff to a talented Colombia side, who returned to the finals for the first time since 1962. Mexico, condemned to the playoffs after being beaten home and away by Costa Rica, and losing to their American neighbours for the first time since the sixties, would again sit out on the sidelines, though they were at least guaranteed to qualify for 1994, having been awarded hosting rights in 1986. Elsewhere, Argentina and Uruguay both qualified comfortably for the finals, with Argentina qualifying despite missing Maradona for several games due to an injury suffered with Roma, though he was expected to be a key figure at the finals, as Argentina under former River Plate manager Héctor Veira, looked to win a second title.

In Asia-Pacific, Korea qualified comfortably alongside the United Arab Emirates who qualified for the first time under Bora Milutinović.

[9] New Zealand, who had debuted in 1982, secured the final spot after seeing off the Republic of China in a playoff, having the satisfaction of condemning Australia to finishing third in their group thanks to a double from Werder Bremen’s Wynton Rufer.

[10] Asia’s competitive qualification had yet to translate into sustained success at the finals, though Korea were confident that they might finally qualify from the group stage for the first time. In Africa, Egypt returned to the finals for the first time after several decades of drift, though they had regularly challenged for continental titles, while Cameroon qualified after missing out on the 1986 tournament, with the side containing several veterans of the 1982 side which had far exceeded expectations. The final slot, settled in the final round, saw South Africa see off the challenge of Nigeria thanks to a goal from Roy Wegerle, who had followed his brothers into professional football, having moved to England via the American Soccer League. South Africa, who had a strong domestic league and several overseas internationals, were expectant that they could follow some of their continental counterparts and qualify for the knockout stages.

Participating nations

- Soviet Union (hosts)

- Brazil (holders)

- Argentina

- Austria

- Cameroon

- Costa Rica

- Colombia

- Czechoslovakia

- Egypt

- England

- Germany

- Ireland, Republic of

- Italy

- Korea

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Romania

- Scotland

- South Africa

- Spain

- United Arab Emirates (debut)

- United States

- Uruguay

- Yugoslavia

The draw, held in Moscow on 9 December 1989, saw the Soviets and Brazil seeded as hosts and holders for the group stage, joined by Germany, England, Italy and Argentina, though the French would have been seeded ahead of the Argentines if they had qualified due to their superior performances at the preceding two tournaments.

Seeded teams: Soviet Union (hosts), Brazil (holders), England, Germany, Italy, Argentina

The draw was as follows:

Group A: Soviet Union, Spain, Cameroon, United Arab Emirates

Group B: Brazil, Scotland, United States, Yugoslavia

Group C: Argentina, Romania, Costa Rica, Netherlands

Group D: Germany, Czechoslovakia, New Zealand, South Africa

Group E: Italy, Ireland, Colombia, Korea

Group F: England, Uruguay, Egypt, Austria

Tournament summary

Group A

Group A, split between Moscow and Leningrad paired the Soviet hosts with Spain, Cameroon and debutantes U.A.E. coached by former Soviet international manager and coach Konstantin Beskov. The opening game, played at the Central Lenin Stadium in Moscow, saw the Soviets ease to a 4-1 win over the U.A.E. with a double from Igor Dobrolovski and goals from Ivan Yaremchuk and Volodymyr Lyutyi seeing the Soviets establish an unassailable lead, though Adnan Al Talyani scored the Emiratis debut goal. The game, played in front of a capacity crowd, saw the atmosphere punctuated by chanting against recent price increases, as the marketisation reforms continued apace.

[11]

Elsewhere, Spain and Cameroon played out a foul tempered draw as both sides physicality boiled over, following a particularly rough tackle by André Kana-Biyik on Miguel Pardeza sparking a brawl between the two sides, before Kana-Biyik was sent off. Despite the physicality there were flashes of both sides skill, as Julio Salinas was superbly denied by Thomas N’Kono in the Cameroonian goal before François Omam-Biyik gave the African side a surprise lead thanks to a superb volley. Spain’s equaliser, which saw Emilio Butragueño collect a mishit clearance, drive past two tacklers and fire beyond the reach of N’Kono became the final punctuation point to a game of brutal tackling, with Spanish substitute Quique Sánchez Flores lucky to not be sent for a vicious tackle on Cameroonian veteran Roger Milla.

In the second round of games, the Soviets and Spain played out a goalless draw enlivened by a pre-match parade of veterans from the Spanish Civil War (for if there’s nothing the Soviet authorities would waste more than industrial capacity, it’s the chance to have a parade of some sort) as both nations Heads of State (President Adolfo Suárez & General Secretary Yuri Andropov) watched on. If the parade had a degree of pomp and circumstance, the game itself was a drab one, with the teams playing out a goalless draw, so devoid of chances that neither goalkeeper had a stained shirt.

Elsewhere, Cameroon eased to a 2-0 victory over the Emiratis with goals from captain Stephen Tataw and substitute Eugène Ekéké proving too much for the Middle Eastern side. The game, Cameroon’s first victory at the finals, would become infamous due to a protest from the Emirati delegation after an equaliser was chalked off for a foul on N’Kono, with Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, son of the Emir of Qatar and Emirati Sports Minister running onto the field and protesting the decision with the French referee before leading his players off the pitch, in farcical scenes.

In the final fixtures, Spain eased to a 5-0 victory over an astoundingly passive U.A.E. who exited their debut tournament with a whimper, though if rumours were to be believed not entirely empty handed as the Soviets and Emiratis would sign a memorandum of understanding over trade in the aftermath of the tournament. The game itself however was not an even contest, as the Spanish attack carved through an Emirati defence so lacking in resistance, that it was Spanish profligacy which kept the score down. Elsewhere, the Soviets eased to a 1-0 win over Cameroon, thanks to an own goal from Benjamin Massing, to top the group.

Group A

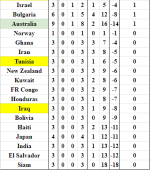

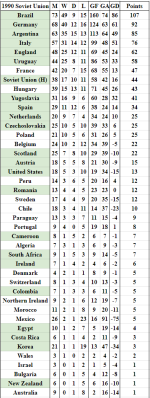

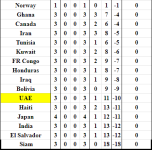

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Soviet Union | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | +4 | 5 |

2 | Spain | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 | +5 | 4 |

3 | Cameroon | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | +1 | 3 |

4 | U.A.E. | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 11 | -10 | 0 |

Results

8 June Soviet Union 4-1 United Arab Emirates

9 June Spain 1-1 Cameroon

13 June Soviet Union 0-0 Spain

14 June United Arab Emirates 0-2 Cameroon

18 June Spain 5-0 United Arab Emirates

18 June Cameroon 0-1 Soviet Union

Group B

Group B paired holders Brazil with 1986 hosts the United States and two European sides in Scotland, and an exceptionally talented Yugoslavia whose squad contained several players from their triumphant run of World Youth Championship trophies in the late 1980s. The group, split between Kiev and Minsk was largely expected to be a straight fight between Brazil and Yugoslavia.

The opening game saw Brazil ease to a 1-0 victory over the Scots, thanks to a deflected header from Romário, whose emergence as a goalscoring phenomenon at the 1988 Olympics (memorably scoring five in a game against a hapless Korea) had seen him move from Rio side Vasco da Gama to Belgian side Anderlecht. The game itself, was not a classic, as two workmanlike sides built around power and athleticism cancelled each other out, though despite the somewhat fortuitous nature of Brazil’s winner, Scotland offered next to nothing as an attacking threat.

If Brazil had been somewhat fortuitous in victory over the Scots, the same could not be said for Yugoslavia’s cruise against the Americans, as the Yugoslavs eased to a 5-1 win, thanks to an unplayable midfield performance from Dragan Stojković, and strong contributions from a talented support cast including Dejan Savićević, Darko Pančev and Robert Prosinečki. The game, which had seen the Americans take the lead against the run of play in the first half thanks to an Eric Wynalda thunderbolt, was over as a contest by the half hour, after a Savićević hat-trick. The game, played in a backdrop of almost normalised relations between the two superpowers

[12] had been the subject of local jokes about who Stalin would have supported.

[13] Despite the mismatch, the game itself did have some memorable moments – Yugoslavia’s superb performance with the ball, mesmeric in its balletic grace to quote some of the more purple descriptions of the tournament was a joy to watch, as they tore apart the American defence with scalpel precision. Indeed, if not for an inspired performance from goalkeeper David Vanole, the score could have been much worse.

The second round of games saw Scotland ease to a 2-1 win over a much improved American side, thanks to goals from Mo Johnston and Ally McCoist, with McCoist’s fortuitous winner sealing victory for Scotland in the final minutes. The Americans, switching to a 5-4-1 formation after the failed experiment with a sweeper in their opening game, proved obdurate opposition, with Uruguayan born midfielder Tab Ramos particularly impressive. While not the most skilful of contests, the game was high on drama, as a late American winner from substitute Eric Eichmann was wrongfully ruled out for offside, before McCoist’s scuffed shot deflected in off the unfortunate Jimmy Banks to settle the game in Scotland’s favour.

In Kiev, Brazil and Yugoslavia played out a tense classic, with the Brazilians eventually prevailing thanks to Vujadin Stanojković’s sending off in the second half – as always with the brittle Yugoslav national team, the greatest enemy lay within. Despite the man advantage, Brazil’s more physical approach struggled to break down the Yugoslav backline, as a game which had waxed and waned as a contest became increasingly frenetic, before Careca took advantage of Stanojković’s harsh second yellow card to settle the game with a late penalty.

[14]

In the final round of games, Brazil who had largely played with endeavour but no real finesse improved to ease to a comfortable 2-0 victory over the Americans in Minsk, with a strong performance from American reserve goalkeeper Tony Meola keeping the score down. Playing a largely second string side, with veteran Antônio Cerezo captaining the side

[15] Brazil scored either side of half time thanks to the raw power of Romário, whose brace took him to three goals for the tournament and kickstarted the latest Brazilian press hype overdrive, anointing him Dico’s heir apparent (despite their very different styles of play.) Brazil’s victory, achieved with minimal fuss, with the exception of one brilliant save from Cláudio Taffarel to deny John Harkes. The victory saw Brazil top the group without ever having really excelled, and consigned the Americans to the wooden spoon, a disappointing return after the heroics of their home tournament four years earlier.

In Kiev, Yugoslavia held firm in the face of a relentless Scottish long-ball attack, to win 1-0 sealing second place in the group. The goal, a glancing header from veteran Faruk Hadžibegić, settled the tie in the eightieth minute, as the Scots wilted in the face of having to secure an equaliser, with the last five minutes petering out into a damp squib, to see Yugoslavia through as second in the group.

Group B

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Brazil | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | +4 | 6 |

2 | Yugoslavia | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 2 | +4 | 4 |

3 | Scotland | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | -1 | 2 |

4 | U.S.A. | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 9 | -7 | 0 |

Results

9 June Brazil 1-0 Scotland

10 June Yugoslavia 5-1 United States

14 June Scotland 2-1 United States

15 June Brazil 1-0 Yugoslavia

19 June United States 0-2 Brazil

19 June Yugoslavia 1-0 Scotland

Group C

Group C paired two previous winners in the Netherlands and Argentina with Romania and Costa Rica, both sides making a return to the finals for the first time in decades, with the sides split between Volgograd and Rostov, leading to a memorable image from the tournament of stars such as Maradona and Gullit being photographed at the Stalingrad War Memorial.

The opening round of fixtures saw the Dutch draw 1-1 with Romania in a game let down by a poor pitch, though the technical ability of both sides was on full display, with Steaua star Gheorghe Hagi particularly impressing. His opening goal, a deft lob over Hans van Breukelen, brought the crowd, largely local with a few pockets of orange, up from the brink of torpor, injecting some much needed atmosphere.

[16] The Dutch equaliser was however more indicative of the largely poor quality on display, as Marco van Basten’s scuffed shot, took a deflection on a divot to wrong foot Romanian goalkeeper Silviu Lung – a goal somewhat emblematic of the largely poor football on display throughout the tournament’s group phase.

Elsewhere, in Rostov, Argentina eased to a 1-0 victory over a spirited Costa Rica, with Diego Maradona sparing the South Americans blushes with a late winner. The game, while not high in quality overall, drew criticism back in Argentina, for how sluggish and muted the team’s performance was – indeed their performance was regarded as so poor that opposition politician Eduardo Angeloz used it as a jibe on the economy in a presidential debate against rightist incumbent Álvaro Alsogaray.

[17] Costa Rica, despite the defeat, drew widespread praise for their tenacious performance, particularly striker Hernán Medford, who would become the first Costa Rican to play in Serie A after the tournament, when he signed with Genoa.

In the next round of games, the Romanians would secure their second consecutive draw of the tournament, with Gavril Balint’s late equaliser, tucking home after Argentina’s goalkeeper Luis Islas failed to hold a speculative shot from Ioan Sabău, cancelling out Claudio Caniggia’s opener. In contrast to both sides opening matches, this was an entertaining contest, with both sides relying on a fast-passing style to try and win through. Billed as a contest between Maradona and one of his many pretenders in Gheorge Hagi, the match largely bypassed both with Hagi below par and being substituted on the hour mark, while Maradona was ruthlessly marked out of the game by Ioan Andone, leaving a draw as something of a fair result.

The Dutch, hampered in their opening game by a poor pitch and a somewhat arrogant dismissal of the Romanians, improved in Rostov to eased to a 3-1 win over the Costa Ricans, with substitute Wim Kieft scoring twice before captain Ruud Gullit sealed the victory in the final ten minutes of the game. Despite the comfort of the score, the Dutch initially struggled to break down the Costa Ricans, whose 5-4-1 formation had caused real issues for the Argentines, and were behind thanks to a goal from captain Róger Flores. Cheered on by the local crowd, Costa Rica looked to be heading for a superb upset, as the wave after wave of Dutch attack failed to breach Gabelo Conejo’s goal , before Hans Kraay’s decision to replace the surprisingly ineffectual Marco van Basten with PSV’s Kieft paid dividends.

The final round of fixtures featured the most anticipated game of the group stages as the Dutch and Argentina faced off in Volgograd, having largely flattered to deceive in both their preceding fixtures. The game, expected to be a classic, was a damp squib in both senses of the word, as a thunderstorm delayed kick-off for ten minutes, before the two sides played out a bad-tempered 0-0 draw, with both Pedro Monzón and Gerald Vanenburg sent off, following a clash after a bad tackle on Vanneberg by Monzón. Following the end of what some would charitably describe as a contest, the two sides continued to argue with each other, before both Kraay and Argentina manager Héctor Veira exchanged strong words and gesticulation. Romania, who had drawn their first two games, secured their win at the finals in decades, with goals from Rodion Cămătaru, Hagi and Marius Lăcătuș seeing them secure a 3-0 win over Costa Rica in Rostov, condemning the Central Americans to last place in the group, despite their tenacious performances.

Group C

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Romania | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2 | +3 | 4 |

2 | Netherlands | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | +2 | 4 |

3 | Argentina | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | +1 | 4 |

4 | Costa Rica | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 7 | -6 | 0 |

Results

10 June Netherlands 1-1 Romania

11 June Argentina 1-0 Costa Rica

15 June Argentina 1-1 Romania

16 June Costa Rica 1-3 Netherlands

20 June Netherlands 0-0 Argentina

20 June Romania 3-0 Costa Rica

Group D

Group D, split between Baku and Tblisi., paired previous champions Germany with Czechoslovakia, New Zealand and South Africa, with the Germans and Czechoslovaks largely expected to qualify with ease.

The opening game, played in a sweltering Baku, saw Germany ease to a 2-0 win over a spirited New Zealand, with the New Zealanders keeping Germany goalless until the eightieth minute when substitute Ulf Kirsten scored twice in five minutes as the New Zealanders began to flag. Despite the scoreline, New Zealand managed to cause Germany’s defence problems, with Werder Bremen’s Wynton Rufer testing Eike Immel, while Hull City’s Harry Ngata pace caused Klaus Augenthaler significant problems, before Dresdner SC’s Kirsten settled the game. If Germany struggled to break down obstinate, if somewhat limited opponents, Czechoslovakia appeared to be cruising to a fairly routine 1-0 victory over South Africa, before Roy Wegerle scored one of the goals of the tournament – picking up the ball on the halfway line, he drove past two attempted challenges, flicked the ball over the onrushing Luboš Kubík before collecting it and firing home beyond the reach of Luděk Mikloško to settle the game as a draw.

In contrast to the somewhat bloodless atmospheres at some of the matches not involving the hosts or more storied nations, both Baku and Tblisi, two football obsessed cities in the more stereotypically hot-headed southern republics, brought a ferocious atmosphere, despite the general lack of non-local fans at the games.

[18] While in Baku, this was largely concentrated on the football, Tbilisi’s febrile atmosphere coincided with increasing nationalist agitation for independence from the Soviet Union, which had, in contrast to the largely peaceful demonstrations in the Baltics, seen widespread scenes of violence as police clashed with demonstrators. This difference in atmosphere was perhaps best seen in Germany’s victory over the South Africans in Tbilisi, as the game was delayed for an hour, following the effects of tear gas from clashes between the local police and demonstrators outside the ground, while in Baku, New Zealand’s scoring of a goal against the Czechoslovaks was greeted with delirium.

In the matches themselves, the two European sides eased to 3-1 victories over their African and Asia-Pacific opposition, with Germany improving from their stuttering performance against the New Zealanders in their opening match, thanks largely to a superb performance from the veteran playmaker Bernd Schuster who had been restored to the national side by Bernd Stange on the eve of the finals.

[19] Schuster, often mercurial and prone to falling out with team-mates and managers at both club and international level was simply unplayable, with only an inspired performance from South Africa’s captain Gary Bailey, who had returned to South Africa to play for the Orlando Pirates in the country’s top flight, keeping the South Africans in the game. If Schuster was revelatory, scoring once and setting up the other two, Germany’s defence was perhaps lucky that the partnership of Noel Cousins and veteran Andries Maseko offered little threat, as South Africa’s consolation goal came from an awful error from Matthias Sammer, who’s attempted clearance fell straight to midfielder Neil Tovey who fired home for his only international goal. In Baku, Czechoslovakia held off a strong New Zealand fightback thanks to a hat-trick from Stanislav Griga, as the New Zealanders wilted in the latter stages, after taking a surprise lead through Rufer, who’s gloriously dinked finish left Mikloško no chance. The game, despite the sheen of the result, was competitive, as New Zealand, well drilled under Chilean coach Orlando Aravena, took the game to their more illustrious opponents, before Czechoslovakia’s greater fitness began to tell.

In the final round of games, Germany drew 1-1 with Czechoslovakia thanks to an own-goal from Ivan Hašek after Sparta Prague’s Michal Bílek had given the Czechoslovaks the lead. The game, played at the Dinamo Stadium in Tbilisi was not a classic, though a superb save from Immel denied the Czechoslovaks victory, with both sides perhaps glad to leave the sweltering heat behind them, as well as the city’s somewhat volatile atmosphere. In Baku, long-time sporting rivals New Zealand and South Africa met for the first time in a football match since the 1970s, with both countries Prime Minister’s in attendance.

[20] The game, saw New Zealand secure their first point in six matches at the finals as goals from Rufer and Rapid Vienna’s Chris Zoricich saw them come back from two goals down to draw against South Africa, with an uncharacteristic error from Bailey, who misjudged the flight of Zoricich’s attempted cross handing New Zealand the draw, with the South Africans finishing third.

Group D

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Germany | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 2 | +4 | 5 |

2 | Czechoslovakia | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 | +2 | 4 |

3 | South Africa | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | -2 | 2 |

4 | New Zealand | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | -4 | 1 |

Results

9 June Germany 2-0 New Zealand

10 June Czechoslovakia 1-1 South Africa

14 June South Africa 1-3 Germany

15 June Czechoslovakia 3-1 New Zealand

19 June Germany 1-1 Czechoslovakia

19 June New Zealand 2-2 South Africa

Group E

Group E paired 1982 hosts Italy with Ireland, South Americans Colombia (both making their first appearance at the finals since the 1960s) and perennial Asian participants Korea, with games split between Odessa and Kharkiv. Italy, whose national side had struggled as their clubs thrived during the 1980s were largely expected to win the group with a shootout for second between a functional Irish side and Colombia whose unpredictability saw them viewed as potential dark horses. Only Korea, who had long since become Asia’s standard bearer at the World Cup looked like making up the numbers, with their European stars of yesteryear now retired.

The opening game, between Italy and Colombia in Odessa, saw the Italians ease to a 2-0 victory thanks to the clinical finishing of Gianluca Vialli and substitute Salvatore Schillachi, who had been a surprise pick for the tournament, despite an excellent domestic season with Juventus.

[21] Despite being picked as potential outsiders for the tournament by Dico, Colombia struggled to break through Italy’s defence, and found themselves behind thanks to better quality finishing, though the Italians were indebted to Walter Zenga for a superb save from Colombian substitute Miguel Guerrero for keeping the score 0-0 before half time. In Kharkiv, Ireland, unused to being cast as favourites, found themselves in a position of trying to break down a side even more functional in style, resulting in one of the most turgid halves of football yet seen at an increasingly turgid tournament. The game, while failing to improve as a spectacle in the second half, did at least see a clear result as substitute Niall Quinn’s scuffed shot evaded the grasp of Choi In-young to give the Irish their first ever victory at the finals, in a game swiftly (and thankfully forgotten.)

The second round of games saw the Italians ease to a 1-0 victory over Korea thanks to an early goal from Paolo Maldini, who’s belted finish from the edge of the box left Choi with no chance. As Korea, well-organised but with next to no attacking threat, failed to offer any real chances against Italy, and the Italians content to see out the game as a one goal victory, the last eighty minutes passed by with no real urgency –

antifutbol in its logical extreme. The local fans, bored of the lack of entertainment in front of them, amused themselves with paper planes made from flyers from tournament sponsors Budweiser, creating one of the more surreal images of a surreal tournament. Elsewhere, Ireland and Colombia drew 1-1 as a late equaliser from substitute Frank Stapleton saw snatch a late point after Carlos Valderrama, who had been anonymous against Italy, put in a performance of unplayable skill, dictating play and setting up Colombia’s opener for Carlos Estrada to score his first international goal – indeed if not for a superb intervention from Steve Staunton, he could have sealed the victory.

[22]

The final round of games saw the Italians and Irish meet in a game of stultifying tedium which would mercifully finish after ninety minutes, though for many of those covering it they perhaps wished it could’ve ended sooners. To be fair to both sides, neither were helped by local weather conditions in Kharkiv – stifling summer heat giving way to thunderstorms and high humidity, resulting in a pitch resembling treacle more than a sports pitch at a World Cup, not that FIFA or the television companies were minded to care too much. At least the match was televised. If Ireland and Italy’s 0-0 draw could be regarded as a one of the least competitive games in tournament history, let alone a competitive football match, Colombia’s victory over Korea was at least decisive if not a classic contest, with veteran striker Arnoldo Iguarán’s double enough for Colombia to ease to victory over stubborn if limited opponents, with only a mistake from Colombia’s eccentric goalkeeper René Higuita, who spilt a mishit cross into the path of Lee Sang-yoon, who couldn’t miss.

Group E

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | Italy | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | +3 | 5 |

2 | Ireland | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | +1 | 4 |

3 | Colombia | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | -1 | 3 |

4 | Korea | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | -3 | 0 |

Results

12 June Italy 2-0 Colombia

13 June Ireland 1-0 Korea

17 June Italy 1-0 Korea

17 June Colombia 1-1 Ireland

21 June Ireland 0-0 Italy

21 June Korea 1-2 Colombia

Group F

Group F, the most geographically split of the groups with games played in Yerevan and Moscow (over two-thousand kilometres apart) paired England, who had followed up finishing third in 1986 with a dreadful performance at the 1988 European Nations Cup, three-time champion Uruguay, Austria and Egypt who were returning to the finals for the first time in decades.

The opening game, played in Yerevan, saw England and Austria draw 1-1 after a late equaliser from Gary Lineker cancelled out Toni Polster’s deserved opener, as the English, whether due to Yerevan’s summer heat, the surreal atmosphere within the ground itself, or the inexplicable decision of Dave Sexton to start the veteran Peter Shilton for his sixty-third cap ahead of the long-established Chris Woods.

[23] Shilton, to put it mildly, had a poor game, with only Austria’s wasteful finishing seeing them fail to capitalise. Things would turn on the half hour mark, as Austria’s key midfielder Andi Herzog withdrew injured, dulling Austria’s midfield edge, with England eventually growing into the game, before Lineker saved their blushes (and a point) in the closing minutes of the game. Elsewhere, Uruguay, who had frequently failed to spark in previous tournaments, saw off a rugged Egyptian side 2-0, thanks to goals from Lazio’s Rubén Sosa and captain Enzo Francescoli, who had long established himself as a languid player of extraordinary ability, to give the South Americans the perfect tournament start.

In the second round of games, England, having made several changes to their side, with Woods restored to the starting line-up, alongside former captain Ray Wilkins, whose form for Monaco in Ligue 1 had seen him called up to the squad after a three-year absence. Wilkins, never the fastest player, proved a languid presence on the ball, dictating play from a withdrawn role in front of the defence, with England able to pass their way through a well organised Egyptian side. Two goals from Peter Beardsley, and a late goal from John Barnes saw England secure a reasonably comfortable victory. Austria and Uruguay, playing in Moscow, drew 0-0, though the match was at least reasonably compelling with Polster and Sosa both close to securing winners for their respective sides.

England, playing a lopsided 4-3-3, were perhaps lucky to be playing their toughest opponent last, as they moved to Moscow to face the Uruguayans. Uruguay, a side transformed into a less brutal, if still physical side, under the coaching of Óscar Tabárez, who had led Peñarol to continental glory and victory in the Intercontinental Cup in a superb five year spell, would prove to be difficult opponents for the English, whose reliance on Wilkins and substitute Hoddle for midfield invention would see their play become sluggish as both midfield veterans struggled to get into their rhythm. Indeed, England were indebted to Chris Woods for a superb reflex save to deny Carlos Aguilera a late winner – nevertheless both sides would finish the group stage unbeaten. In Yerevan, Austria and Egypt drew 1-1, with a late penalty from Magdi Abdelghani securing Egypt’s first point at the finals in decades, while Austria would finish unbeaten.

Group F

Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Points |

1 | England | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | +3 | 4 |

2 | Uruguay | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | +2 | 4 |

3 | Austria | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

4 | Egypt | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 | -5 | 1 |

Results

11 June England 1-1 Austria

12 June Uruguay 2-0 Egypt

16 June England 3-0 Egypt

17 June Austria 0-0 Uruguay

21 June Uruguay 0-0 England

21 June Egypt 1-1 Austria

Ranking of third place teams

| Group | Team | Played | Won | Drawn | Lost | GF | GA | GD | Points |

| C | Argentina | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | +1 | 4 |

| A | Cameroon | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | +1 | 3 |

| F | Austria | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| E | Colombia | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | -1 | 3 |

| B | Scotland | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | -1 | 2 |

| D | South Africa | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | -2 | 2 |

Following the conclusion of the group stage, the second round was drawn in Moscow on June 22, and was a follows:

Match 1: C1 vs. A3: Romania vs. Cameroon (Minsk)

Match 2: E1 vs. D2: Italy vs. Czechoslovakia (Odessa)

Match 3: B2 vs. F2: Yugoslavia vs. Uruguay (Kiev)

Match 4: A1 vs. E3: Soviet Union vs. Colombia (Moscow)

Match 5: A2 vs. C2: Spain vs. Netherlands (Kharkiv)

Match 6: D1 vs. F3: Germany vs. Austria (Rostov)

Match 7: B1 vs. C3: Brazil vs. Argentina (Leningrad)

Match 8: F1 vs. E2: England vs. Ireland (Volgograd)

Round of Sixteen

The round of sixteen saw the host cities contract to the European republics of the Soviet Union, partially for ease of travel and partially for political reasons. The opening match, pairing Romania with Cameroon, saw the Romanians win a tightly contested affair 2-1 in extra time, with substitute Dănuț Lupu scoring the decisive goal. The game, a tense affair light on chances, but high on tension, saw the Cameroonians push the Romanians hard, before Romania’s younger bench came into play. The victory saw Romania reach the quarter finals for the first time since the 1930s.

In Odessa, Italy were indebted to Salvatore Schillachi, whose late brace eased them past a stubborn Czechoslovakia who were aggrieved to see an equaliser from Tomáš Skuhravý wrongly ruled out for an adjudged foul on Walter Zenga. The refereeing performance was further criticised by the Czechoslovaks for the failure to send off Nicola Berti for two rough tackles, failing to even caution him for a scything challenge on Ľubomír Moravčík. The bad temper would continue after the final whistle, with the normally reserved and professorial Jozef Vengloš, Czechoslovakia’s coach engaged in an intense debate with the Austrian referee before being eventually escorted off the pitch by his own players.

In Kiev, Yugoslavia, whose incredibly talented side had emerged as favoured dark horses for some of the watching press put Uruguay to the sword, with the Uruguayans unable to deal with the Balkan side’s midfield interplay, in a display of technical brilliance rarely seen at the 1990 tournament. Dragan Stojković, Dejan Savićević and Robert Jarni all proving too strong for a surprisingly brittle Uruguayan defence to cope with as the Yugoslavs romped to a 3-0 victory.

In Moscow, the hosts held their nerve to see off Colombia 5-4 on penalties after the game had finished 1-1, with Higuita making a superb save in the dying moments of extra-time to deny Sergei Aleinikov a late winner for the Soviets. The game, played in front of a capacity crowd had seen the Soviets intricate passing style cause issues for the South Americans, who resorted to fouling their opponents to keep the game alive – indeed, it says much about their efforts that their equaliser came from an own goal, as the unfortunate Sergei Gorlukovich sliced a horrendous clearance into his own net. Nevertheless, the game itself was a slow burner, and the relief on display as Andrei Zygmantovich buried the final penalty beyond the reach of Higuita demonstrated how close they had been to exiting their own tournament.

In Kharkiv, a late penalty from Ronald Koeman gave the Dutch victory over Spain, whose chances had taken a significant hit when Emilio Butragueño was injured in the warm-up, with the Dutch fortunate that his replacement Miguel Pardeza was a much more straightforward striker – marked out of the game by Frank Rijkaard, he made little impact as Spain exited the tournament with a whimper.

In Rostov, the Germans saw off neighbours Austria with a comprehensive victory as goals from Karl-Heinz Riedle, Ulf Kirsten and a double from Jürgen Klinsmann saw them four goals up by the hour mark, with Austria shellshocked. Easing their foot off the gas, and perhaps aided by the removal of Lothar Matthäus, the Austrians were able to nick a late consolation through Toni Polster.

The penultimate tie, which pitted holders Brazil with neighbours and rivals Argentina was hotly anticipated, with much prophesising of a titanic clash between two sides of attacking verve (written clearly by journalists who had failed to watch either side’s group stage fixtures.) Inevitably, the game was a damp squib – Brazil, while still containing some flair, were a workmanlike outfit compared to the all-conquering side of four year prior, while Argentina, a better side than given credit for, but certainly not one to set pulses racing, were defensive in outlook. The game, such as it was, featured numerous incidences of skullduggery, foul play and petulance and very little football, before Maradona, perhaps bored of the contest himself, settled the game with a contemptuous volley, leaving Cláudio Taffarel with no chance, sending the holders home.

The final tie, pitting England against the Irish Republic, was held during a backdrop of generally strong Anglo-Irish relations, as the IRA’s terror campaign was in one of its lulls and the general amenability of British and Irish Prime Ministers John Moore and Desmond O’Malley.

[24] The match itself, pitting two sides known for a focus on physical play and the odd piece of invention was dire, with England scraping through in the dying moments of extra-time thanks to a late goal from Terry Butcher, who ran onto David Platt’s late through ball to slide home past Packie Bonner in the Irish goal to settle the tie in England’s favour.

Results

23 June Romania 2-1 Cameroon (a.e.t.)

23 June Italy 2-0 Czechoslovakia

24 June Yugoslavia 3-0 Uruguay

24 June Soviet Union 1-1 Colombia (5-4 pens)

25 June Spain 0-1 Netherlands

25 June Germany 4-1 Austria

26 June Brazil 0-1 Argentina

26 June England 1-0 Ireland

Quarter finals

The last-eight paired Romania with Italy, hosts Soviet Union with Yugoslavia, the Dutch with neighbours Germany and England with the sole non-European side Argentina.

The opening game, played in Kiev, saw the Italians win a tightly contested game 1-0 thanks to a late winner from Roberto Baggio, who’s beautifully chipped finish over Silviu Lung enlivened a game light on quality, as Hagi struggled to break through Italy’s barrier like defence. The game, saw Italy reach their first semi-final in six years, after disappointing performances at both USA ’86 and the 1988 European Nations Cup. Romania, despite the somewhat limp exit, returned to a country who’s communist regime were beginning to totter with a degree of pride.

In Moscow, the hosts, buoyed by a large and vocal home support faced off against a technically brilliant Yugoslav side, whose midfield were one of the strongest at the tournament. The game, in contrast to the slightly sterile affair in Kiev, was a good one, both sides playing on the front foot, with both Tomislav Ivković and Rinat Dasayev tested. Yugoslavia took the lead through captain Zlatko Vujović, who headed home from a corner, before as it appeared that Yugoslavia were heading to their first World Cup semi-final in decades, Oleh Protasov buried a late equaliser to take the game to extra time. As both sides tired, and the mental fragility that had undercut both began to tell, the game went to penalties, where both sides proceeded to miss half their kicks, before the Soviets eventually triumphed 3-2 after Faruk Hadžibegić missed the final kick.

In Leningrad, Germany eased to a 2-1 victory over a surprisingly subpar Dutch side, with goals from Rudi Völler and Andi Brehme enough to give the Germans a decisive two goal lead, before a late consolation from Aberdeen’s Hans Gillhaus added a degree of respectability to the scoreline. The match itself was overshadowed by scenes at the end, as both sets of players squared up to each other following a series of bad-tempered clashes over the course of the game, before the normally mild mannered Bernd Stange and Hans Kraay clashed trying to separate their players, bringing a somewhat chaotic end to the Dutch tournament.

The final game, pitted South American hopefuls Argentina against England in Minsk, in a game hampered by a general air of sterility as the Argentines use of a five-man midfield stifled England’s attempts to conduct play through Wilkins. The result, with supply lines cut off to England’s attackers, and Maradona subdued by man-to-man marking, was a tense, goalless contest, with the ball almost entirely contested in the middle of the park. England, with their creativity stifled, resorted to the firm values of “grit” and “passion”, while Argentina held them off through a combination of skilled defending and use of the dark arts, with tactical fouling used across the board. The game itself, failed to ignite as a contest, but was settled late on by a superb Maradona goal, as finally escaping the clutches of Neil Webb, he danced through three attempted challenges and side footed beyond the reach of Chris Woods to break English hearts.

Results

30 June Romania 0-1 Italy

30 June Yugoslavia 1-1 Soviet Union (2-3 pens)

1 July Germany 2-1 Netherlands

1 July Argentina 1-0 England

Semi finals

The semi-finals paired Italy with the hosts in Moscow and Germany with Argentina in Leningrad, with most expecting the Italians to make the final, with the Germany and Argentina game expected to be much tighter as a contest.

In contrast to both sides’ tight contests in the previous round, the Italians proved too good for a tiring Soviet side, with goals from Schillachi and Roberto Donadoni in the first half putting the Italians into an unassailable lead, quietening what had been a tempestuous atmosphere in support of the home side. The second half, saw the Soviets claw a late goal back through Igor Dobrovolski, before Aldo Serena snuffed out any chance of a Soviet comeback.

In Leningrad, Argentina and Germany played out a pantomime of mutual paranoia and sterility, settled by a late Maradona goal which likely should have been ruled out for offside, while Argentina were lucky that Néstor Lorenzo wasn’t dismissed for a brutal two-footed tackle on German substitute Andreas Thom (and even more ludicrously, he wasn’t booked by the Spanish referee.) Nevertheless, despite the fortuitous nature of it, Argentina were through to the final for the first time since winning in 1978.

The third-place playoff, played between two relaxed sides was an entertaining game, eventually won by the Soviets thanks to a free-kick from substitute Ivan Yaremchuk, to secure their best finish at the finals since the 1960s.

Results

3 July Italy 3-1 Soviet Union

4 July Germany 0-1 Argentina

Third Place Playoff

7 July Soviet Union 1-0 Germany

Final

The final, played between two sides who had alternated between occasional brilliance and grinding out results, met in what is possibly the worst final in tournament history, as two defensive sides met in an anticlimactic contest, settled by a late penalty. As extra-time appeared inevitable, both sides became increasingly fractious, with Lorenzo, lucky not to be dismissed in the semi-final sent off for two yellow cards following an altercation with Italian substitute Carlo Ancelotti. Despite the man disadvantage, it would be Argentina who would prevail, as a late foul on Maradona by the otherwise excellent Giuseppe Bergomi, saw the Argentine captain pick himself up and score the decisive goal from the spot. In the end the worst winning side in modern memory won possibly the worst tournament of the modern era.

Result

8 July Argentina 1-0 Italy

[1] Increased tensions in Georgia also saw the hosting committee propose to withdraw Tbilisi but intense lobbying from Georgian Interior Minister Eduard Shevardnadze saw it retained as a host city.

[2] While the party still remained firmly in charge in the USSR, the economic liberalism pursued by the state since the late 1960s, had also seen gradual liberalisation of the public sphere with censorship eased and general repressive measures avoided, the increased liberalisation of the public sphere had seen ling suppressed nationalisms begin to rise to the surface, with the party leadership increasingly minded to reform the Union on more confederal lines.

[3] While nowhere near as liberalised as the Yugoslav model on which it was partially based on, the Soviets had shifted to a less top-down economic structure, though the party still remained firmly in charge.

[4] Despite appearing in some cases as similar organisations to their Western counterparts, these were very firmly state mandated organisations.

[5] The model would be repeated in other parts of the Warsaw Pact as their respective regimes recognised the increasing need to embrace a form of economic liberalisation.

[6] Perhaps the most interesting example of this in a football context was the signing of a deal between Lokomotiv Moscow, the team of the Soviet Railways and the Japanese automotive manufacturer Toyota for the former to play an exhibition tour in Japan in exchange for the mass purchase of Toyota made railway maintenance vehichles.

[7] This was aided, in contrast to the 1978 finals in Iran, by the fact that significant portions of the top echelons of the Soviet state were keen football fans.

[8] Armfield, who won fifty-two caps for England, had been a member of the 1966 squad, and had enjoyed a successful management career in club football, having succeeded Revie as Leeds United manager before managing overseas in the Middle East, Portugal and Greece with success in each, before returning to England to manage Sheffield United to consecutive promotions from the fourth tier to the second, catching the eye of the FAI in Dublin, who appointed them to succeed former international Johnny Giles as Ireland manager.

[9] The U.A.E. who had changed their name from the United Emirates of Eastern Arabia following a series of decrees under the reformist government headed by the Emir of Qatar during the rotating presidency, had become a footballing hub in the Gulf as each respective Emirate through large sums of money at sport.

[10] Rufer, alongside Australian internationals Craig Johnstone and Tony Dorigo, frequently drew the ire of his club coaches for his decision to regularly represent New Zealand, despite the travel distance, something which had also befallen former Bundesliga legend Cha Bum-kun.

[11] Economic history of the Soviet Union is beyond the scope of this work, but the path to a more liberalised economy was becoming reflected within the system’s football ecosystem as domestic stars became increasingly of interest to Western clubs.

[12] The opening ceremony was attended by President Bob Dole, who had returned the Republicans to the White House in 1988, marking the first sporting event in the Eastern Bloc to be attended by a sitting American President.

[13] While the liberalised atmosphere of the Soviet Union in the Andropov era allowed a certain leeway for jokes about the system and past leaders, that leeway only extended so far – several hundred Zalgiris Vilnius supporters had been arrested for organising a pro-independence rally during a game with Dynamo Moscow, marking the extent to which dissent would be tolerated.

[14] Sent off for a harsh handball, following a first yellow for dissent, Stanojković was the first victim of FIFA’s increasingly strict directives on law interpretations for the 1990 tournament.

[15] Cerezo, oft overshadowed by his more illustrious midfield counterparts, equalled the Brazilian record for consecutive finals appearances, appearing in his fourth straight tournament since 1978.

[16] The relaxation of visas for the tournament had extended to the Warsaw Pact members, though with the Soviets looking increasingly inward throughout the 80s they had largely become autonomous actors, outside of military actions, leading some analysts to characterise the bloc as an increasingly loose bloc.

[17] Football’s role in such debates had a long history in Latin America’s intermittent democracies of the twentieth century.

[18] New Zealand’s participation at a second tournament, drew more coverage than the first, while South Africa had long seen football established as a truly pan-racial national sport with the country’s first black Prime Minister, Labour Party leader Steve Biko frequently seen at games, including their multiracial (if predominantly black) squad’s games at the 1990 tournament.

[19] Stange, who had no real playing career of note, had previously served the DFB in various roles from manager of various youth sides before becoming Jupp Derwall’s assistant. After the latter stood down following the 1986 tournament, and after being turned down by several more established names, the DFB appointed Stange manager in 1987, making him at the age of thirty-nine the youngest permanent manager in the country’s history.

[20] Biko, and his New Zealand counterpart David Caygill, alongside Australian Prime Minister Lionel Bowen formed a trio of Labour governments in the southern hemisphere, often acting as a counterbalance to the rightist bent of other major Commonwealth nations, with the Conservatives, Cumann na nGaedheal and the Indian Peoples Party all forming governments of the centre-right during this period.

[21] Giuseppe Materazzi, Italy’s coach was something of a surprise appointment himself, having largely coached in Italy’s lower leagues before leading Lazio to a sustained period of cup success, if largely indifferent league form. Hired after Azeglio Vicini resigned following Euro 88, he like Schillachi was largely seen as a strange choice for the national side.

[22] Colombia, Valderrama in particular, became adopted by the local community in Odessa as they used Chornomorets Odessa’s training facilities as their base. The local side, backed by the Black Sea Shipping Company was one of the Soviet Union’s richer clubs, and had some of the best facilities in the Ukrainian SSR after the state patronaged Dynamo Kiev.

[23] Shilton had largely expected to be in the squad as third choice as his career wound down, following his long decades competing with (and losing to) Ray Clemence for the starting position.

[24] Moore, who had become Prime Minister in 1987 after defeating Labour’s incumbent Dennis Healey in that year’s general election, was something of a maverick having cut his teeth in the American political environment for the Democrats, before returning to Britain as something of a political chameleon, but his youthful image and good looks constrasted sharply with the tired Labour government, seeing the Tories returned to office for the first time since the 1970s. O’Malley in contrast, was a long term government veteran having served as a minister in various coalition governments, before leading Cumann na nGaedheal to victory in the 1982 election.