-

Hi Guest!

The costs of running this forum are covered by Sea Lion Press. If you'd like to help support the company and the forum, visit patreon.com/sealionpress -

Thank you to everyone who reached out with concern about the upcoming UK legislation which requires online communities to be compliant regarding illegal content. As a result of hard work and research by members of this community (chiefly iainbhx) and other members of communities UK-wide, the decision has been taken that the Sea Lion Press Forum will continue to operate. For more information, please see this thread.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Max's election maps and assorted others

- Thread starter Ares96

- Start date

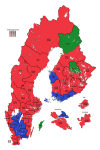

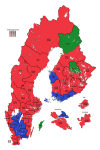

Okay, the constituency results on this don't align even slightly with the total seats diagram (for one thing, they add up to 29-36 more seats than is generally reported), but I don't really see a good way of fixing that at the moment. So this probably isn't going on the DA anytime soon, unless I can find data that does add up.

1900-1903: Adolf Lagerheim (National majority)

1902: National (177), Liberal (84), Radical (64), Labour (17)

1903-1907: Adolf Lagerheim (National leading War Government with Liberals and Radicals)

1907-1908: Adolf Lagerheim (National minority)

1907: National (183), Labour (116), Liberal (66), Radical (51), Middle-Class (5), others (4)

The Great War came to an end. Three and a half years of mindless slaughter on the Karelian front was over, and the soldiers brushed the mud off their uniforms and looked out at the cratered landscape. Borgå, the second-oldest city east of the water, with its prized wooden houses and Romanesque cathedral, lay in ruins, and the harbour of Svensksund was so riddled with mines that it wouldn't reopen for two years. Between the two cities was a swath of death and destruction several miles wide, running from the lakes of Itis to the shore at Strömfors. A generation of Swedish men, as many as a hundred thousand including civilians, lay dead.

And what had it all been for? Almost no territory changed hands at the negotiating table. Viborg, the main war goal of the Swedish Army, remained firmly in Russian hands. Not only that, Sweden bound itself to accept a population transfer of all Swedish-speakers and Protestant Finns east of the border. And Russia had allegedly lost the war - but didn't even have to pay reparations to Sweden for the cities it flattened.

Needless to say, when the news broke, Stockholm erupted into riots that would last four days. It briefly looked as though the monarchy would be overthrown, but the situation was salvaged when the Foreign Office negotiated food relief from the United States (which had remained neutral but was favourably disposed to the Coalition side) and Lagerheim pledged two major changes: firstly, universal suffrage under proportional representation, and secondly, his resignation within a year of the new Riksdag meeting.

The elections were held in September, and were less of a disaster for the Hats than generally expected - though decimated in the major cities, the countryside remained behind Lagerheim and his programme. The big news was the rise of the Labour Party, who captured more seats than the Riksdag had grown by and became the largest party in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Åbo. Lagerheim was able to form his third ministry, a pure National minority administration, and resigned the following spring as promised. Perhaps he was tired of frontline politics, but probably not of politics - he was made a Baron, continued to act as a grey eminence within the party, and died in 1934 at the age of 77.

1908-1910: Gustaf Serlachius (National minority)

Lagerheim was followed by his Finance Secretary, a dull man from the upper end of the Åbo bourgeoisie who had become known for a laconic wit that matched his stringency with public finances. Expected by everyone to serve in the ministry with quiet distinction and then retire to a barony, he instead found himself thrust into power when Lagerheim resigned. He seemed like a good choice - quietly effective, views that matched the post-war direction the Hats were taking, and no faction of the party disliked him particularly. In his time as Chancery President, Serlachius would prove a paradox - at once firmly principled and willing to compromise, at once arrogant toward other parties and able to form composition ministries and hold cabinet with their leaders by his side. These qualities allowed him to pass two budgets in a minority administration, and dissolve the Riksdag in the summer of 1910 to coincide with the Coronation of King Gustav VI.

1910-1912: Hjalmar Munck (National-Radical composition)

1910: National (152), Labour (135), Liberal (54), Radical (43), Left-Socialist (34), Patriotic Electoral League (5), Middle-Class (2)

It was an odd match. If one went back into time and told Augustin Beck-Friis that his party would one day govern alongside the "Phrygians", not ten years after his death at that, the old arch-Hat would probably not have believed it. And yet that was what had happened. Of course, it had already happened during the war ministry, and perhaps that was when the two parties realised their differences weren't as great as either thought. For one thing, they both hated the Caps, and maybe that was enough. For another, the Radicals' centrepiece demand had already been brought in by the Nationals. Serlachius stepped down in favour of Munck, on one hand a nobleman, on the other a known moderniser within the Hats who the Radicals felt they could work with. The budget negotiations were surprisingly smooth, with the parties agreeing on speedy disarmament and generally restrained government spending as the economy began to recover.

Much as this pleased the Phrygians, it went over none too well with the paternalistic, relatively statist rural wing of the National Party, who came more and more into collision with the leadership over the course of 1911. At its congress in the spring of 1912, the National Association of Farmers voted to withdraw support from the Nationals, form a new party and invite individual Hats known to be sympathetic to form a rural faction in the lower chamber. Fifteen members did, and the Munck cabinet fell to a vote of no confidence within days. Munck chose to dissolve the Riksdag rather than cobble together a new composition.

1912-1914: Hjalmar Munck (National-Radical composition)

1912: Labour (141), National (113), Rural (50), Radical (37), Communist (37), Liberal (36), Patriotic Electoral League (11)

The composition government was reformed after all other alternatives had been exhausted, and continued to govern with quiet restraint for the most part. It dealt with the Hats and the Rural League when budget time came around, but didn’t do much the rest of the year. The lack of drama in the Munck II cabinet was all the more conspicuous given the increasing instability of the country as a whole. The Communist Party on the left was increasing its agitation, organising miners in the far north, shipbuilders in Gothenburg and Åbo and indentured farmworkers in the plains of central Sweden against the existing social order. On the right, a group of anti-disarmament Hats had joined with the Front Fighters’ Association and parts of the National Youth League to form the Patriotic Electoral Association (Fosterländska Valmansförbundet, FVF), which blamed the labour movement for stabbing Sweden in the back and inspiring the mutinies that ended the war, and held regular rallies calling for a restoration of national glory. The FVF were fast nicknamed the "Helmets", a name that stuck with them throughout their existence.

Things were inevitably headed for chaos, and it arrived in June 1914, when news broke of the Boliden conflict. Miners at Boliden in Västerbotten had come out on strike that spring, and finding no replacement labour in the company town, the management had applied for relief workers from the College of Social Affairs, which was granted. The news that the government was employing strikebreakers caused outrage in leftist circles, and a demonstration at Kungsträdgården led to street brawls between left-wing and right-wing mobs. Sporadic clashes continued throughout the summer, and when the Riksdag reconvened in August, the government was voted out.

1914-1915: Erik Andersén (nonpartisan caretaker cabinet)

With Munck and Serlachius refusing to take the premiership and no opposition coalition able to muster a majority, the King appointed a caretaker administration led by the first nonpartisan Chancery President since the reign of Gustav III. Andersén had been a leading law professor at the University of Uppsala, then served as Chancellor of Justice under Lagerheim and Serlachius. While tied to the Hats in this, he had never joined the party, and commanded broad respect across both chambers of the Riksdag. His cabinet achieved little of note - it wasn't meant to - and presided over a Riksdag election every bit as chaotic as that of 1912, resigning as soon as a new composition could be formed.

1915-1917: Carl Albert Albertsson (Labour-Radical composition)

1915: Labour (153), National (98), Radical (46), Communist (43), Liberal (41), Rural (37), Patriotic Electoral League (7)

At last, it was Labour's turn. It had been twenty years since they were first elected to the Riksdag, and they had beaten the Hats into first place in two consecutive elections. Perhaps tennis rules had brought them to power - or perhaps it was the change in leadership in the Radical Party that caused them to break with the Hats in favour of an untested new centre-left composition. It very nearly captured a majority of the lower chamber - only passive Communist support was needed to pass a radical budget for 1916. The Lords initially threatened to block it, but a demonstration outside the House of Nobility reminded them of their narrow mandate, and convinced enough noble Lords to abstain from voting. The first public pension, the progressive estate tax, the payroll tax, were all brought in by the 1916 budget, and the following year would see thoroughgoing poor law reform and the introduction of equal suffrage in local elections. It was when the turn came to labour issues that the composition began to crack. The Labour backbenches wanted the 40-hour work week to be made mandatory, as did the Communists, but the Phrygian leadership was divided on the issue. Twenty-two Radical members ended up voting against the bill, enough for it to fall, and Albertsson tendered his resignation the following day.

1917-1918: Kaj Boije af Gennäs (National minority)

The new ministry was as unexpected as its Chancery President, a geriatric Hat baron whose only previous cabinet experience was under Beck-Friis back in the 1890s. Boije's only real recommendation was the fact that he was a regular Saturday guest at Drottningholm, and the fact that he held dirt on nearly every senior member of the National Party in the Riksdag (the latter fact only becoming known upon the release of his memoirs, which precipitated three high-level resignations in the cabinet and, according to legend, multiple suicide attempts). His administration was a caretaker one in practice, with little to differentiate it from the Andersén cabinet except insofar as nearly all the members were Hats.

1918-1921: Johan Adolf Boberg (National-Rural-Liberal composition)

1918: Labour (133), National (123), Rural (59), Radical (41), Communist (36), Liberal (28), Patriotic Electoral League (5)

The new composition was the first majority administration since the war, and represented a coming together of the entire opposition during the previous Riksdag except the Helmets. Johan Adolf Boberg was known as a dynamic man of the younger generation, not unlike Lagerheim when he came to power, although he was in fact only six years younger than Lagerheim (then again, most people would look young and dynamic next to Boije). He was the first Chancery President to have served in the Great War - obviously not as a frontline soldier, but as an officer in the Lappland Rangers. He had led the capture of Pechenga, one of few Swedish victories in the late phase of the war, and this made him famous well before he stood for the Riksdag as a Hat in 1910.

Another peacetime first was the inclusion of both Hats and Caps in a composition - the latter party had been decimated by the Hats, Phrygians and Rural League, and retained its former strength only in a few peripheral regions. They were now the smallest party in the composition, which ended up dominated by the Hats and the ex-Hats and other conservatives who made up the Rural League. When the "wolf winter" of 1918-19 brought about a four-week delay in the planting season, the government acted fast to save the livelihoods of Northern farmers, and tax breaks for smallholders was a major thrust of the 1920 budget. The trend of disarmament was reversed for the first time since the war in the 1920 Defence Order, which provided for two new regiments to be raised and the construction of six new armoured hemmemas for the Archipelago Fleet.

Perhaps it was appropriate that the first Hat-Cap composition in decades would fall apart over trade policy. The agricultural crisis had not been staved off by the emergency aid, as fields decayed and grain importation began to become feasible again. The Rural League proposed a new grain tariff, and after a long and raucous cabinet debate, the Hats and the College of Commerce came out in support. The Liberals saw no recourse but to go into opposition, even though the bill failed - Labour were not about to vote for a deliberate hike in food prices.

1921-1922: Johan Adolf Boberg (National-Rural composition)

Boberg was able to reform his administration as a Hat-Rural composition, with the Liberals providing outside supply and confidence on the condition that the tariff issue not be revisited. This was honoured, and indeed, the Boberg II cabinet would be unable to get much of anything done given the global economic crash that began in the autumn of 1921. A budget for 1922 with reduced expenditure in nearly every field was passed, and the remaining time was spent battling crisis after crisis, both in the treasury and in the streets of Stockholm. The situation grew tense, but when elections were called for September of 1922, Boberg had at least survived an entire term as Chancery President and dissolved the Riksdag on his own terms - something few heads of government can claim even today.

1922-1923: Johan Adolf Boberg (National-Rural-Liberal composition with Patriotic support)

1922: Labour (154), National (83), Rural (59), Communist (46), Patriotic Electoral League (38), Radical (21), Liberal (21), Monetary Reform (3)

And indeed, he would return for the new Riksdag, even though the parliamentary arithmetic was far less favourable. The three parties that had held a majority in 1918 controlled only about forty percent of the seats in 1922, and passing legislation would require support from the Helmets as well as the various "middle-class" independents elected amidst the chaotic 1922 campaign. It was untenable from the beginning - even a man like Boberg could only barely juggle three parties, let alone four and a half. Staying in office for eight months was itself a remarkable achievement.

1923-: Axel Wahlberg (Labour-Rural composition)

1923: Labour (179), National (68), Rural (57), Communist (47), Radical (25), Patriotic Electoral League (25), Liberal (23), Monetary Reform (1)

The second Labour government, the first one to survive a full parliamentary term,

Last edited:

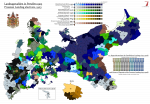

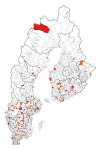

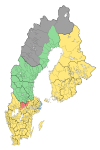

And some more byproducts - with advice* from DrakonFin on the other place, I've fixed** the county boundaries east of the water for TTL:

(yes, they look fuck-ugly on the reformed boundaries, but that's realistic, just look at the western half of the country which I barely changed from OTL)

*Advice which I chose not to follow

**Boundaries may be subject to future change

(yes, they look fuck-ugly on the reformed boundaries, but that's realistic, just look at the western half of the country which I barely changed from OTL)

*Advice which I chose not to follow

**Boundaries may be subject to future change

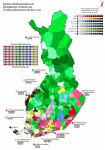

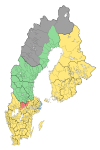

And here's the same with parties.

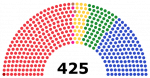

Labour Party (His Majesty's Government): 207

Communist Party of Sweden (informal support: 14

National Party (Official Opposition): 125

Rural League: 57

Liberal Party: 17

Finnish People's Party and Finnish Independents: 5

This is perhaps the least weird TTL's Swedish party system has been since the Great War, and the least weird it will ever be (bearing in mind that the TL's present is the mid-1970s).

Labour Party (His Majesty's Government): 207

Communist Party of Sweden (informal support: 14

National Party (Official Opposition): 125

Rural League: 57

Liberal Party: 17

Finnish People's Party and Finnish Independents: 5

This is perhaps the least weird TTL's Swedish party system has been since the Great War, and the least weird it will ever be (bearing in mind that the TL's present is the mid-1970s).

1949-1954: Markus Öhman (Labour minority)

1949: Labour (207), National (125), Rural (57), Liberal (17), Communist (14), Finnish (5)

1954-1963: Johannes Grahn (Labour leading Labour-Rural composition)

1954: Labour (176), National (136), Rural (66), Communist (21), Liberal (15), Finnish (11)

1959: Labour (181), National (134), Rural (71), Liberal (21), Communist (12), Finnish (6)

1963-1967: Mikael Ahlström (National leading National-Rural-Liberal composition)

1963: Labour (154), National (142), Rural (64), Liberal (27), Communist (15), Finnish People's Party (15), Greens (5), Isänmaanliitto (3)

1967-1972: Gustaf Knutsson (Labour leading Labour-Rural-Green composition)

1967: Labour (145), National (136), Rural (44), Finnish People's Party (31), Isänmaanliitto (15), New Alliance (15), Liberal (14), Communist (14), Greens (11)

1972-: Gustaf Knutsson (Labour leading Labour-Rural-Green composition)

1972: Labour (151), National (104), Finnish People's Party (67), Rural (28), New Alliance (21), Greens (17), Communist (13), Liberal (12), Isänmaanliitto (12)

Subject to change. In particular, I think the Communists should be bigger and the Hats smaller - although ideally without moving too much support directly from one to the other.

1949: Labour (207), National (125), Rural (57), Liberal (17), Communist (14), Finnish (5)

1954-1963: Johannes Grahn (Labour leading Labour-Rural composition)

1954: Labour (176), National (136), Rural (66), Communist (21), Liberal (15), Finnish (11)

1959: Labour (181), National (134), Rural (71), Liberal (21), Communist (12), Finnish (6)

1963-1967: Mikael Ahlström (National leading National-Rural-Liberal composition)

1963: Labour (154), National (142), Rural (64), Liberal (27), Communist (15), Finnish People's Party (15), Greens (5), Isänmaanliitto (3)

1967-1972: Gustaf Knutsson (Labour leading Labour-Rural-Green composition)

1967: Labour (145), National (136), Rural (44), Finnish People's Party (31), Isänmaanliitto (15), New Alliance (15), Liberal (14), Communist (14), Greens (11)

1972-: Gustaf Knutsson (Labour leading Labour-Rural-Green composition)

1972: Labour (151), National (104), Finnish People's Party (67), Rural (28), New Alliance (21), Greens (17), Communist (13), Liberal (12), Isänmaanliitto (12)

Subject to change. In particular, I think the Communists should be bigger and the Hats smaller - although ideally without moving too much support directly from one to the other.

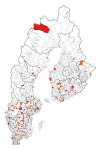

A project long in the works has finally been completed. (of course, I spotted an error within minutes of writing that)

Hundreds of Sweden, ca. 1800

Before the modern municipal system was introduced, the main administrative unit between parish and county level in Sweden was the hundred. Originally, the Götaland provinces were divided into härader, which each had its own local thing with a chieftain (häradshövding) who normally represented the most prominent family in the hundred but was sometimes subject to competitive election at the thing, while Svealand had hundare, which also served a judicial function but were mainly units of military service, each contributing one hundred men to the ledung, and had things chaired by one of two hundare-judges appointed by the King. Over time, the two types of unit merged together, taking the härad name and the title of häradshövding for the chief judge, but operating more like the old hundare.

On the peripheries of Svealand, units with different names persisted, though their functions were no different from those of the härader in practice. On the coast of Uppland, the largest and richest Svealand province, was Roslagen, a region dominated by maritime trade and plundering expeditions who didn't contribute men to the ledung, but rather ships. As such, they were never divided into hundare, but rather skeppslag, and this name carried on into the 20th century.

Similarly, the northwest periphery of Svealand lay the traditional mining districts of Bergslagen, which operated under special laws following the German pattern. A bergslag was originally a corporation of farmers who collectively held the right to operate mines in a particular area, but over time it came to refer to the area as a whole, and the reforms of Axel Oxenstierna in the 17th century brought mining under the control of Bergskollegiet (the College of Mountains) in Stockholm, leaving the bergslag as hundreds with a different name.

(Karlskoga is a special case - it was consistently referred to as Karlskoga bergslags härad, taking both styles)

What united all three forms of hundred were extreme administrative inertia. Their boundaries stayed exactly the same until the 1870s, and even then the only changes made were to bring parishes formerly divided under a single hundred. Substantive changes wouldn't happen until the great judicial reform of 1971. They weren't really needed either - Swedish peasants pre-19th century were famously sedentary, few ever leaving their home parishes let alone hundreds, and their populations remained stable (if grossly unequal) through the centuries.

The main task of the hundreds was local administration of justice - the häradsting morphed into local courts, and law enforcement was handled by a kronolänsman assisted by four fjärdingsmän ("farthing-men") in each hundred. Some of the bigger hundreds were divided into tingslag, which had a court each, and most häradshövdingar served groups of hundreds called domsagor. The law stipulated that fines should be split three ways between the crown, the plaintiff and the hundred, with the hundred's third again divided between the hundred as a legal person, the tribunal of lay judges and the häradshövding. This made the position of häradshövding lucrative, and attracted a lot of noblemen who used the title as a cash cow and never even visited their hundreds. Several different reforms tried to reduce this risk, with limited success, but by 1800 the nobility's right of precedence to häradshövding positions had at least been abolished.

So what did the hundreds themselves do with their ninth of fine income? Well, part of it went to maintaining the courts themselves, but the 1734 legal code also charged hundreds with maintaining public roads and guesthouses, as well as the hundred-commons (häradsallmänningar) and fisheries that had been their responsibility since time immemorial. More closely connected to the courts were also the hundred gaols and archives. Most of these functions were transferred either to the state (acting through the county administrative boards) or the municipal councils in the 1862 reform, and when an 1891 law created special road districts, the last non-judicial function of the hundreds went away.

For reasons that escape me, the hundred system was never implemented north of Dalälven. Well, there was one hundred in Dalarna (Folkare, which may have been part of Västmanland in medieval times), but with that exception, all of Dalarna and Norrland was divided directly into domsagor and tingslag, of which the former often encompassed entire provinces, while the latter was usually only a couple of parishes, being small enough that parties in court cases should be able to get to the thing and back in a day. Ideally - obviously this was not the case in the far north. The domsagor and tingslag were less autonomous than hundreds, with all administrative functions carried out by appointed officials. Each domsaga had a judge who rode circuit between the different tingslag, and other tasks normally handled at hundred level were carried out by the parish meetings (AFAIK).

When I say "all of Norrland" that's a bit of a lie. There were also the lappmarker, which covered areas far enough north that agriculture wasn't possible. These areas were dominated by Sami people (hence the name) and had absolutely no semblance of local government. The lappmarker were taxed, but could not vote, their inhabitants were tightly controlled by crown officials, and in the 19th century, efforts would be undertaken to forcibly Swedify them. That was all in the future in 1800, but suffice it to say life in the lappmarker was unfun.

In Finland, the härad name was used, even though only Finland Proper had any real history of medieval Swedish administrative units by that name. Its five hundreds (six with Åland) were also the only ones that behaved anything like hundreds in southern Sweden - the others all resembled Northern domsagor more closely, and their boundaries changed frequently. A major boundary reform was undertaken in 1775, when the new counties of Vasa and Kymmenegård were created, and the Russians would change the boundaries again in the 1840s. Again, reasons for this naming choice escape me.

EDIT: Two more errors spotted and corrected. Never say anything's completed, folks.

Hundreds of Sweden, ca. 1800

Before the modern municipal system was introduced, the main administrative unit between parish and county level in Sweden was the hundred. Originally, the Götaland provinces were divided into härader, which each had its own local thing with a chieftain (häradshövding) who normally represented the most prominent family in the hundred but was sometimes subject to competitive election at the thing, while Svealand had hundare, which also served a judicial function but were mainly units of military service, each contributing one hundred men to the ledung, and had things chaired by one of two hundare-judges appointed by the King. Over time, the two types of unit merged together, taking the härad name and the title of häradshövding for the chief judge, but operating more like the old hundare.

On the peripheries of Svealand, units with different names persisted, though their functions were no different from those of the härader in practice. On the coast of Uppland, the largest and richest Svealand province, was Roslagen, a region dominated by maritime trade and plundering expeditions who didn't contribute men to the ledung, but rather ships. As such, they were never divided into hundare, but rather skeppslag, and this name carried on into the 20th century.

Similarly, the northwest periphery of Svealand lay the traditional mining districts of Bergslagen, which operated under special laws following the German pattern. A bergslag was originally a corporation of farmers who collectively held the right to operate mines in a particular area, but over time it came to refer to the area as a whole, and the reforms of Axel Oxenstierna in the 17th century brought mining under the control of Bergskollegiet (the College of Mountains) in Stockholm, leaving the bergslag as hundreds with a different name.

(Karlskoga is a special case - it was consistently referred to as Karlskoga bergslags härad, taking both styles)

What united all three forms of hundred were extreme administrative inertia. Their boundaries stayed exactly the same until the 1870s, and even then the only changes made were to bring parishes formerly divided under a single hundred. Substantive changes wouldn't happen until the great judicial reform of 1971. They weren't really needed either - Swedish peasants pre-19th century were famously sedentary, few ever leaving their home parishes let alone hundreds, and their populations remained stable (if grossly unequal) through the centuries.

The main task of the hundreds was local administration of justice - the häradsting morphed into local courts, and law enforcement was handled by a kronolänsman assisted by four fjärdingsmän ("farthing-men") in each hundred. Some of the bigger hundreds were divided into tingslag, which had a court each, and most häradshövdingar served groups of hundreds called domsagor. The law stipulated that fines should be split three ways between the crown, the plaintiff and the hundred, with the hundred's third again divided between the hundred as a legal person, the tribunal of lay judges and the häradshövding. This made the position of häradshövding lucrative, and attracted a lot of noblemen who used the title as a cash cow and never even visited their hundreds. Several different reforms tried to reduce this risk, with limited success, but by 1800 the nobility's right of precedence to häradshövding positions had at least been abolished.

So what did the hundreds themselves do with their ninth of fine income? Well, part of it went to maintaining the courts themselves, but the 1734 legal code also charged hundreds with maintaining public roads and guesthouses, as well as the hundred-commons (häradsallmänningar) and fisheries that had been their responsibility since time immemorial. More closely connected to the courts were also the hundred gaols and archives. Most of these functions were transferred either to the state (acting through the county administrative boards) or the municipal councils in the 1862 reform, and when an 1891 law created special road districts, the last non-judicial function of the hundreds went away.

For reasons that escape me, the hundred system was never implemented north of Dalälven. Well, there was one hundred in Dalarna (Folkare, which may have been part of Västmanland in medieval times), but with that exception, all of Dalarna and Norrland was divided directly into domsagor and tingslag, of which the former often encompassed entire provinces, while the latter was usually only a couple of parishes, being small enough that parties in court cases should be able to get to the thing and back in a day. Ideally - obviously this was not the case in the far north. The domsagor and tingslag were less autonomous than hundreds, with all administrative functions carried out by appointed officials. Each domsaga had a judge who rode circuit between the different tingslag, and other tasks normally handled at hundred level were carried out by the parish meetings (AFAIK).

When I say "all of Norrland" that's a bit of a lie. There were also the lappmarker, which covered areas far enough north that agriculture wasn't possible. These areas were dominated by Sami people (hence the name) and had absolutely no semblance of local government. The lappmarker were taxed, but could not vote, their inhabitants were tightly controlled by crown officials, and in the 19th century, efforts would be undertaken to forcibly Swedify them. That was all in the future in 1800, but suffice it to say life in the lappmarker was unfun.

In Finland, the härad name was used, even though only Finland Proper had any real history of medieval Swedish administrative units by that name. Its five hundreds (six with Åland) were also the only ones that behaved anything like hundreds in southern Sweden - the others all resembled Northern domsagor more closely, and their boundaries changed frequently. A major boundary reform was undertaken in 1775, when the new counties of Vasa and Kymmenegård were created, and the Russians would change the boundaries again in the 1840s. Again, reasons for this naming choice escape me.

EDIT: Two more errors spotted and corrected. Never say anything's completed, folks.

Last edited: