I suppose I'd better start posting the actual election maps too. First off, I should note that I don't have constituency boundaries for anything prior to 2008, so these maps kind of have to be a bit more abstract than you're used to. Hopefully someday I'll be able to track down the boundaries, but today is not that day.

So as mentioned in the local government post, Nepal was an absolute monarchy for most of its history, with first the Rana family, the king's hereditary chief advisors, and then the kings themselves holding supreme power over the country's governance. The "democratic revolution" of 1950-51, which overthrew the Ranas, had been spearheaded by the

Nepali Congress, a left-wing group inspired by the INC who hoped the Rana regime would give way to, if not a socialist republic, then at least a modern constitutional monarchy. After all, India had just recently become an independent, secular republic, and Nehru's nominally-socialist INC government had been the key foreign backer of the revolution. In the end, however, it turned out the royal house was uninterested in going from being a figurehead for the Ranas to being a figurehead for an elected parliament. Although a second mass protest wave in 1957-58 succeeded in forcing free parliamentary elections in spring 1959, the parliament thus elected and its Congress-dominated government only lasted eighteen months before King Mahendra launched a self-coup, dissolving parliament and throwing most of its leading figures in jail.

To Mahendra's mind, Nepal, which had been isolated from the surrounding world until the overthrow of the Ranas and remained an extremely poor, underdeveloped country, was simply not ready for liberal democracy. Instead, he designed his own system of government which he believed more closely resembled traditional Nepalese systems of governance and would allow the people to be represented in the fashion they best understood and were able to engage with. This was the

panchayat system (not to be confused with the

panchayati raj system, which is in use in India and refers specifically to local government), and it would be in use in Nepal for the better part of thirty years. A panchayat (meaning "council of five" in Sanskrit) is the traditional name for a village's governing council in the Indian subcontinent, and these village councils would indeed form the centrepiece of Nepalese governance under the panchayat system. The adult inhabitants of a village would meet and elect a nine-member panchayat (confusingly, most institutions called panchayats in the modern day have more than five members), which would then each delegate one member to sit on the local district council (

zila panchayat). The district councils would in turn choose delegates to a zonal assembly (

anchal sabha), which had very few powers in its own right and functioned mainly as an electoral college choosing representatives to the

Rastriya Panchayat, the national parliament, from among the representatives on each district council. The Rastriya Panchayat was composed of 90 district representatives - no district elected more than two members, which meant the densely-populated Terai (plains) districts were greatly underrepresented - as well as 19 sectional and university graduate representatives and 16 royal appointees. And while official sectional organisations, representing women, youth, the elderly, peasants, labourers and ex-servicemen, did have official representation on all levels of government, political parties were banned from operating.

Obviously, a large part of the motivation for this system was to prevent the opposition from organising above the village level and ensure that the king could effectively govern the country as he pleased. Whether it was the

only motivation, or if Mahendra was actually sincere about wanting Nepal to develop along its own path into a place where it could one day be "ready" to adopt a more democratic form of government, is a purely academic discussion, because what the panchayat regime was in practice was a thinly-veiled royal dictatorship. While some social progress was made during the years from 1960 to 1990 - malaria was mostly eliminated, a highway was built along the foothills connecting east and west, and land use reforms brought the Green Revolution to Nepal and ensured that more of the Terai than ever before was put under cultivation. But the regime's brief attempts at redistributive land reform in the 60s came to naught, and what little wealth the country had remained in few hands while the vast majority of the people lived in or near poverty. Discontent rose throughout the period, and limited concessions in the early 80s (including the direct election of the Rastriya Panchayat's district representatives, although they were still required to be nonpartisan) did little to ease tensions.

The sequence of events that brought down the panchayat regime began with the August 1988 earthquake, which had its epicentre in the Saptari district of the eastern Terai and hit both Nepalese and Indian communities hard, killing at least 709 people, injuring thousands and damaging buildings as far away as Patna. Rescue and reconstruction efforts were mounted, but not as quickly as the situation warranted, and there were soon rumours that members of the government were embezzling international aid money meant for the earthquake victims. Around the same time, the renegotiation of a trade agreement between Nepal and India turned sour, and when Nepal attempted to turn to China for both arms and essential goods, India responded by allowing the agreement to lapse in March 1989. Since India was (and to an extent still is, though China is working on it) the only viable land-based trading partner Nepal has, this did immediate and severe damage to the Nepalese economy. Particularly so for petroleum products, which Nepal depended almost entirely on India for, and which were now impossible to source. Without viable motorised transport, heating or machinery, and without the ability to export Nepalese goods over the country's only negotiable land border, the economy ground to a halt for months.

As I mentioned, resistance to the panchayat system had been ongoing since 1960, but the fuel crisis of 1989 brought it to the surface. The crisis was so severe, and the opportunity so obvious, that the two leading forces of the democratic opposition - Congress on the one hand, and the communist movement on the other - decided to come together and jointly plan a protest action to force the panchayat regime to its knees. On the 15th of January, 1990, the formation of the

United Left Front was announced, bringing together seven of the roughly a dozen or so communist parties in Nepal, and on the 1st of February, the ULF and Congress formed a joint committee to coordinate opposition to the regime. This was the broadest coalition since 1960 - arguably since the original democracy movement in 1950 - and when it went into action on the 18th of February, it brought the country to its knees. Starting with a relatively isolated movement of party activists, protests began to spread after police shot a student during demonstrations in the east of Nepal, and by the end of March, mass protests were engulfing the Kathmandu Valley. Residents of Lalitpur/Patan, a relatively large town just south of Kathmandu, responded to local police violence by establishing a local committee of public safety, closing entrances to the town with roadblocks and placing policemen in detention. Elsewhere in the valley, locals organised blackouts in areas where protests were due to happen, making it much harder both to identify protesters and to employ force against them, and protests got so large and so radical that the opposition committees were losing control.

King Birendra, Mahendra's eldest son, attempted to satisfy protesters on the 6th of April, by announcing that Prime Minister Marichman Singh Shrestha, who had been in charge during both the earthquake and the trade crisis, would be removed and replaced with Lokendra Bahadur Chand, who had previously served as Prime Minister between 1983 and 1986. Chand may have been slightly more competent than Shrestha, but he was still a conservative monarchist, and his appointment did exactly nothing to please the crowds. By this point, chants calling for the king's head were a regular occurrence, and even the police were often unwilling to intervene, preferring to simply watch as protesters smashed cars and statues of King Mahendra. Birendra had only two choices by this point: either cave to the opposition's demands entirely or get killed as protesters ransacked the palace. Wisely, he chose the former - on the 8th, Congress and ULF leaders were invited to the palace for negotiation, and came out with an agreement promising to re-legalise political parties and hold free and direct elections to a national legislature. The king tried to retain Chand as Prime Minister in the interim, but this led to another (slightly less intense) wave of protests, and at the end of that, Congress leader Krishna Prasad Bhattarai was appointed Prime Minister leading a transitional government.

Although the goals of the

Jana Andolan, or People's Movement, as it's become known to history, were now essentially met, there were immediate ruptures within the communist movement over where to go next. A large faction within the ULF wanted to contest the upcoming elections jointly with Congress, reasoning that they'd worked well together during the uprising and would probably continue to do so in an election campaign. However, the Congress leadership were divided on this - Bhattarai was open to the idea, but Girija Prasad Koirala, brother of the late Bisheshwar Prasad Koirala, who'd led Congress during the 1950s and been Nepal's first democratically elected Prime Minister, was staunchly opposed. This was mostly on pragmatic grounds, as he wanted to apply for development aid from the United States, which he had been warned might not be forthcoming if a future Congress government included communists. After a heated internal debate, the Congress national conference in January 1991 rejected the alliance by a narrow margin. The spurned ULF moderates decided instead to found a new unified organisation, which they gave the characteristically straightforward name

Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist), usually abbreviated simply as

UML. While formally led by Sahana Pradhan, the widow of original Communist leader Pushpa Lal Shrestha, in practice the UML was run by its young general secretary, Madan Kumar Bhandari. Bhandari had been a student activist in the 1970s, then got recruited by Shrestha as part of a younger generation of communist leaders - having been born in 1951, he was too young to have participated in the original democracy movement, pointedly unlike both the Congress leadership and most other senior figures within his own party. He is remembered today for developing the concept of "People's Multiparty Democracy", an adaptation of earlier Marxist-Leninist thought to a post-Cold War reality, which called for communists to carry on the class struggle within a liberal democratic framework, contesting free elections against other parties and using the power thus gained to work for the improvement of material conditions.

It goes without saying that this idea was not without controversy among militant communists, many of whom derided it as revisionism or social democracy in a new form. This view was especially pronounced among supporters of the

United People's National Movement, which had been formed in 1989 by those communist parties that thought the ULF insufficiently radical. Generally inspired by Maoism, the UPNM rejected cooperation either with Congress or with the monarchy, and called for an immediate constitutional convention to create a Nepalese people's republic. It too faced division after the Jana Andolan, with one of the two main groups, led by Mohan Bikram Singh, continuing to advocate an electoral boycott since the new constitution had been worked out through compromise with the old regime, a regime he regarded as impossible to compromise with. The other group, led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal (remember that name, he's going to become very important later on) and Baburam Bhattarai (no relation to K.P.), regarded this as a strategic mistake, believing the new government would need to have a genuine communist presence to prevent Bhandari's exceedingly moderate line from completely dominating the left. Along with parts of the left opposition of the ULF, the Dahal-Bhattarai faction of the UPNM would end up forming the

Communist Party of Nepal (Unity Centre), which reaffirmed its commitment to underground work in preparation for the people's war they believed inevitable, while also forming a front organisation, the

United People's Front of Nepal, which would contest the general election and use it as an opportunity to spread the message of revolution. Bhattarai took up the leading position in the UPFN, while Dahal stayed underground and continued to lead the CPN(UC)'s cadres.

Meanwhile, Congress was also shifting right. Having previously been a relatively radical force in Nepalese politics, advocating for a secular democratic republic and opposing the panchayat regime through all means available, it now suddenly found itself a party of power leading His Majesty's government. While K.P. Bhattarai and others continued to espouse left-wing beliefs, they were quickly becoming outnumbered by what were called

panchas - panchayat-era bureaucrats who now entered politics as a way to maintain their power in their local communities. Particularly in the west of Nepal, the pancha faction came to dominate the Congress organisation. The panchas were welcomed by G.P. Koirala, ever the pragmatist, who saw in them only a chance to keep the party's (and by extension, his family's) influence growing, but their role in Congress, and in Nepalese democracy by extension, would have devastating consequences in the years to follow.

For anyone who's concerned that these divisions in the former opposition camp might mean a victory for royalist forces is about to come, don't be. They were at least as chaotic. In a lot of developing countries, right-wingers tend to distrust liberal democracy and prefer to play a supporting role to conservative institutions, and this was to some extent also true in Nepal - if you base your entire worldview on the idea that the king is a rightful absolute ruler and should be vested with complete power over society, then it can seem counterintuitive to stand for election to a parliament intended to check or supplant royal power. However, just as some Maoists chose to participate in elections despite regarding constitutional monarchy as illegitimate, so too some royalists chose to participate in elections despite regarding liberal democracy as illegitimate. Just after the Jana Andolan, a group of leading royal officials formed the

Rastriya Prajatantra Party (National Democratic Party), which was intended to represent the forces of tradition, respectability and Hinduism in the political sphere, now that the king wasn't able to use his full powers in their defence anymore. The RPP soon split in half, however, following what seems to be a proud Nepalese tradition, into a more conservative faction led by our old friend Lokendra Bahadur Chand, and a slightly more liberal faction led by Surya Bahadur Thapa, who had been Prime Minister between 1965-69 and then again 1979-83. Thapa seems to have been one of the few panchas who genuinely believed in democratic development, and even spent a while in jail between his two terms as Prime Minister for giving a speech where he demanded democratic reforms.

At long last, after about a year of preparation, constitutional wrangling and recovery from the chaos of the Jana Andolan, Nepal went to the polls on the 12th of May, 1991. The new Parliament was bicameral, with an upper house called the National Assembly (

Rastriya Sabha) and a lower house called the House of Representatives (

Pratinidhi Sabha). Information on the former is scarce, and I honestly don't even know the basics of how it worked in this period, so this series will focus entirely on the latter for the time being. The Pratinidhi Sabha was made up of 205 members, elected by universal suffrage (18 years old to vote, 25 to stand for election) by plurality in single-member constituencies. Each of Nepal's 75 districts was guaranteed one seat, with the remaining 140 distributed at least somewhat according to population - some changes were made for the election after this, but they weren't huge all things considered. I don't imagine I need to get into the pros and cons of FPTP here, but it was the system used by India as well as most other countries in the region, and this made it the most obvious system for Nepal to adapt. Generally speaking, electorates ranged from about fifty to eighty thousand, with a few much smaller seats in the mountain districts and, I think, some larger ones in Kathmandu in this election.

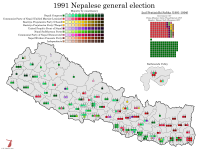

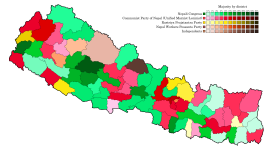

The results were predictable in that Congress won - the combination of having led a revolution against a deeply unpopular regime and also having access to the rural patronage networks that had supported that regime is both hard to obtain and hard to beat - but the details were more surprising. Far from the landslide victory predicted, or the one that they likely would've obtained had the united Congress-ULF front come to pass, they won 110 seats, an overall majority of 15. While they did very well in the western and central regions of the country, in the east, which had formerly been thought of as the main Congress stronghold, the UML completely crushed them. So too in the Kathmandu Valley. The most surprising result of the night came in Kathmandu-1, the seat covering the centre of the capital, where K.P. Bhattarai stood as the Congress candidate and Madan Bhandari for the UML. To almost everyone's surprise, the much younger and less well-known Bhandari won by a small margin, knocking out the Congress leader and making him ineligible to serve in government according to the constitution he himself had just written. The RPP, meanwhile, was hamstrung by its division into two factions, and ended up winning only four seats in spite of their around 12% of the popular vote combined. Their MPs were outnumbered both by the Maoist UPFN and by the

Nepal Sadbhavana Party, a regional party in the Terai that championed the rights of the local Madhesi ethnic groups.

With Congress in the majority but missing K.P. Bhattarai from its party bench, there was only one obvious candidate for the premiership: Girija Prasad Koirala. Following in the footsteps of both of his elder brothers, Koirala formed his government on the 26th, becoming the first democratically-elected Prime Minister of Nepal in over thirty years. He would persist in office through the entire parliament, neither resigning, losing his coalition, getting removed by his party or getting overthrown in a coup d'état - a feat no Nepalese government since has managed. Is that to say he was a

successful Prime Minister? Well, not quite...