Tarzan, king of the jungle

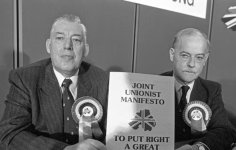

After a dreadful time for Willie Whitelaw, precipitated by the defection of 24 MPs to form the Unionist Party, conspirators still on the Conservative backbenches now wondered if they should mount a coup against their leader. Letters of no-confidence were soon flying in to the chair of the 1922 Committee (guardian of the Tory rulebook). One restless MP said: "A month ago, you would have found five or six people who would sign a piece of paper for it. Now the number is up to at least 9. We have now come to the crisis point." Mr Whitelaw's allies directed their fire at his old rival Michael Heseltine, for a highly damaging allegation that the leader was surrounding himself with yes-men in central office. Francis Pym regarded these remarks as "self-indulgent to the point of madness". Branding it the "worst time possible for anyone to raise the leadership question", he added: "Since he has put the issue of the leadership centre stage, we have to say this is a serious miscalculation and is not in the interests of the Conservative Party or the country at large." Other hitherto loyal MPs said that this latest crisis was entirely created by Whitelaw and his deteriorating relationship with Mr Heseltine, whom he appointed treasury spokesman only in October. An experienced shadow minister said: "I have never seen the party so rudderless. Issue after issue is being bungled." On 14 January 1985, Gallup released a poll for The Daily Telegraph that would bring the leadership its death knell. The Liberal/SDP Alliance scored 37%, Labour 32%, Conservatives 15% and Unionists 13.5%. Two days later at Prime Minister's Questions, the Tory chief attacked the Government over crime, a key touchstone. He was cheered by his own backbenchers; however, Mr Whitelaw failed to land a real blow on David Steel in what was a competent but hardly rousing performance. "We have the opportunity to decide whether or not we want to plunge the party into internal warfare," he told the BBC.

Making a short statement outside the Conservatives' imposing Westminster headquarters, accompanied by his wife Celia, Whitelaw said he would stand down immediately and give the next leader his full loyalty before retiring at the next election. In a rapid sequence of events, Michael Heseltine announced he would run - and Nigel Lawson, a prominent monetarist now in charge of foreign policy, publicly threw his weight behind the shadow chancellor. Mr Heseltine also received the backing of Leader in the Commons Geoffrey Howe and shadow technology secretary Kenneth Clarke. Figures from the right of the party including home affairs spokesman Leon Brittan announced that they would "step aside" to maintain party unity. Most Tory wets left in Parliament resigned themselves to the fact that a quick and bloodless succession was essential to restore public opinion. This made it less of a political contest and more of a coronation. In his pitch to members, Heseltine offered a change from both Thatcherism and moderation. A man of strong emotions, he had come to detest the Iron Lady's divisive effect on the party and nation. So he was too carried away for cold-eyed calculation and the Heseltine team was not well-stocked with political strategists, many of whom (from the 1983 leadership race) had since defected to the SDP. However, in the absence of a challenge, he was able to pursue a vision without compromise. There were economic right-wingers who saw Mr Heseltine as an election winner and a self-made tycoon who, in his own words, stood a better chance of preventing "the ultimate calamity of a Labour government".

Making a short statement outside the Conservatives' imposing Westminster headquarters, accompanied by his wife Celia, Whitelaw said he would stand down immediately and give the next leader his full loyalty before retiring at the next election. In a rapid sequence of events, Michael Heseltine announced he would run - and Nigel Lawson, a prominent monetarist now in charge of foreign policy, publicly threw his weight behind the shadow chancellor. Mr Heseltine also received the backing of Leader in the Commons Geoffrey Howe and shadow technology secretary Kenneth Clarke. Figures from the right of the party including home affairs spokesman Leon Brittan announced that they would "step aside" to maintain party unity. Most Tory wets left in Parliament resigned themselves to the fact that a quick and bloodless succession was essential to restore public opinion. This made it less of a political contest and more of a coronation. In his pitch to members, Heseltine offered a change from both Thatcherism and moderation. A man of strong emotions, he had come to detest the Iron Lady's divisive effect on the party and nation. So he was too carried away for cold-eyed calculation and the Heseltine team was not well-stocked with political strategists, many of whom (from the 1983 leadership race) had since defected to the SDP. However, in the absence of a challenge, he was able to pursue a vision without compromise. There were economic right-wingers who saw Mr Heseltine as an election winner and a self-made tycoon who, in his own words, stood a better chance of preventing "the ultimate calamity of a Labour government".

Last edited: