At this juncture it would be useful to study the various ideas and factions at play in the Coalition. A rich intellectual tradition of modern liberalism had been cultivated since at least the 1930s, when economists John Maynard Keynes and William Beveridge began to pioneer the ideological and structural foundations of the post-WWII settlement. In Britain, a consensus emerged between the main parties, built on five key policies: national ownership of strategic industries, utilities and services; regulation of market forces; collective bargaining for wages via powerful trade unions; social security including benefits, education and healthcare; and progressive taxation to fund it. Liberal planners worked on blueprints for a happier society after the devastation of conflict. The 1942 Beveridge Report detailed answers to the 'five giants' of want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness. He recommended a more fully developed system of national insurance, pension contributions through work, security in old age, welfare grants, financial protection against injury and a universal National Health Service (NHS). Although it was the Labour ministry of 1945-51 which implemented Beveridge's reforms, they carried along the torch of liberalism at least as much as it did socialism. A mixed economy, full employment, trade unionism, welfare and decolonisation served as building blocks in the decades of consensus until 1979. Thatcher's attempt to break with Keynesianism and free the market's 'invisible hand' took inspiration from neoliberal thinkers such as Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek. Her reasoning, that social democracy and welfare were the causes of economic decline and weak growth, led her to adopt a minimalist approach to public expenditure and reverse the tenets of post-war consensus. Her failure, in part because of a strict monetarism with record unemployment as its cost, tore at the fabric of society in the early 1980s. The 'Iron Lady' might have considered herself a latter-day Gladstone, pursuing

laissez-faire and Victorian morals; what followed, rather than a small-state classical liberal utopia, emerged as further industrial strife.

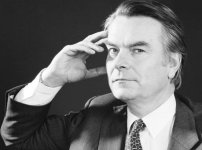

View attachment 78885

Attracting upwardly mobile suburban voters in the 1960s, the Liberal Party responded to the Labour/Conservative dual management of Britain's political settlement by forging a third choice for non-socialist progressives. However, considerable vote shares in the subsequent decade (around 20%) began to fall back as the Liberals were under-represented by the electoral system. Scandals and mayhem in the years of Jeremy Thorpe gave way to a young David Steel, who in 1976 triumphed over John Pardoe to attain the party leadership. While the movement had favoured Gladstonian policies in the 19th century, after Lloyd George they soon championed social reform alongside free trade and civil liberties. 'Positive freedom' entailed government intervention to remove barriers, for example poverty. Their manifesto in 1929 titled 'We Can Conquer Unemployment!' and the Liberal Yellow Book developed a New Liberalism, further inspiring Mr Steel 50 years later. During his early period as leader, members were broadly united around this radical centrism. Liberals recovered from the Thorpe affair and damage inflicted by cooperation with the dying Callaghan ministry, quickly riding to a historic victory in alliance with the SDP. Even so, ideological differences within the party remained. Classical liberals (notably Thorpe and, to some extent, Alan Beith) favoured individual liberty, deregulated market economics, limited government, democratic enfranchisement, the rule of law and free speech. Social liberals advocated wealth redistribution, political and economic rights, promoting justice. This made up the vast bulk of members, including both 1976 candidates. Be that as it may, Pardoe would later describe Steel as having "always been" a social democrat wedded to funnelling money into public services. On a tactical level, many Liberal activists and politicians like him distrusted the leader's easy affiliation with Labour centrists and what became the SDP.

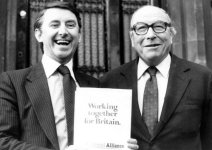

View attachment 78886

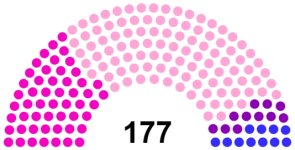

Shirley Williams' leadership enjoyed mass popularity at the grassroots as well as in towns and cities across the nation. Personally charming and relatable, she acted thoroughly well as human face of the Alliance. It was thanks to skilful organising in formerly Labour seats, an almost non-political appeal to voters and modernising innovations that Williams achieved 18% for the SDP in the 1983 general election, coming from nowhere two years prior. Several ideological currents appeared in the party over that time, with considerable overlap between them (as in the Liberals). 'Old Labour' mark 2, centre-left veterans of the Healey camp, lobbied for: Keynesian economic management; large-scale public ownership; government aid to industry; and cooperation between trade unions and state. One proponent was new chancellor Bill Rodgers, who gave similarly minded MPs a key entry point to influence policy in a more Attlee-like direction. Mrs Williams certainly appealed to this group among the wider electorate. The second trend emerged around Roy Jenkins and his centrist ex-Labour faction. Close to the Steel leadership, they strived to protect his liberalising reforms in the 1960s as home secretary and buttress Butskellism, a sardonic term for the proximity between Tory and Labour agendas in the 1950s. Jenkins also wanted a ministry of all the talents in a government of national unity, which clearly became a theme of the 1983 manifesto and campaigning. The SDP could recruit people from all genders and classes, reaching former non-voters. His ideas strongly guided the early months of the Coalition with plans to levy an inflation tax and reduce unemployment.

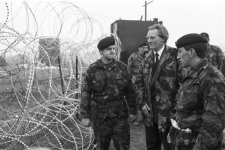

Third are the 'radical idealists' favoured by Williams and David Owen, whom many regarded as being more left-wing than Jenkins in the SDP's formative years. Idealists harboured dreams of ambitiously changing the direction of Britain to face the coming decade. These were: devolution and decentralisation; worker participation in industry; aversion to trade union bureaucracy; profit-sharing and cooperatives; attention to global issues; women's rights; environmentalism; and racial equality. Owen's wing of the party brought converts from educated voters in the growing middle class. Mr Rodgers straddled this radical current and old Labour mark 2, both of whom wished to replace Tony Benn's socialist movement as the foremost progressive choice. Finally, about 10-15% of the SDP belonged to Conservative defectors (e.g. Jim Prior) and Heathite grassroots members. Although their policy demands were relatively undefined - helping to explain Williams' numerous second preferences from Ian Gilmour voters in the 1982 leadership election, despite asymmetrical views. It is true that aside from more egalitarian long-term objectives such as nationalisation of private schools (which ex-Tories were concerned about), Williams' agenda chimed with moderate voters in all directions. Chris Patten, a prominent member of this group, described their role as promoting "economic efficiency and social justice... equality, diversity and civil liberties". On the substance, they resembled the Jenkinsites' technocratic centrism and pro-market Liberals. Development minister Christopher Brocklebank-Fowler acted as a go-between for Heathite 'wets' and the likes of Owen and Williams.

View attachment 78889