-

Hi Guest!

The costs of running this forum are covered by Sea Lion Press. If you'd like to help support the company and the forum, visit patreon.com/sealionpress

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

WI: Sikh Empire conquers Sindh

- Thread starter SinghSong

- Start date

Pretty much. Though in this scenario, Bahawalpur would almost certainly be butterflied away from becoming a British princely state in this scenario, and remain a vassal state of the Sikh Empire instead, unless the British were willing to fight an early Anglo-Sikh War to 'liberate it', along with the portion of Sindh east of Indus; all of which, south of Khairpur, was ruled over by the Mankani branch of the Talpur dynasty, whose ruler was a vocal ally of Maharajah Ranjit Singh and the Sukerchakia dynasty.

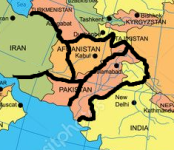

So that's pretty much what the Sikh Empire would be most likely to look like immediately prior to the 1857 Great Mutiny, or its equivalent ITTL, in the event that British East India Company refused to take the changes to the status quo caused by the POD lying down, and having subsequently fought alternate Anglo-Sikh War/s, or initiated conflicts between (or within, if one counts coups and civil wars) its proxies and those of the Sikh Empire by then, in order to 'liberate' Bahawalpur and Khairpur, and with Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur in Mirpur Khas having either been forced to withdraw with his troops to take sanctuary in the Sikh Empire or still leading an active counter-insurgency effort. Or, if the red border's still the border of British India, with the two states in-between still deemed to be nominally independent in spite of their 'Sikh princely state' status.

In the case of Khairpur, if Mir Ali Murad does successfully escape across the border to seek refuge with the British after the initial POD, restoring him to power in (Eastern) Sindh's likely to effectively take precedence for the BEIC, especially for individuals within its administration such as Napier, over restoring Shah Shuja Durrani to the throne of Afghanistan ITTL. Since, with both the Bolan and Khyber Passes firmly under the control of the Sikhs, any plans to do so would either be forced to be indefinitely placed on hold (and thus butterfly away the First Anglo-Afghan War), or would necessitate maintaining a friendlier, closer alliance with the Sikh Empire in order to carry it out. How much might the butterflies of the Sikhs' expansion into Sindh affect other events following on from it, in the wider region and the 'Great Game'?

IOTL, the British chose to pursue the 1st Anglo-Afghan War primarily out of fear that the ruler of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammed Khan, and the Qajar Ruler of Iran, would form an alliance, with one another and with Russia, to invade and extinguish Sikh rule in Punjab, with the over-riding fear that an invading Islamic army would kick off an uprising in India by the people and the princely states. Dost Mohammad had recently lost Peshawar to the Sikh Empire, and was willing to form an alliance with Britain if they gave support to retake it, but the British were unwilling to do so. Considering the Dal Khalsa Sikh army to be a far more formidable threat than the Afghans who did not have a well-disciplined army, Lord Auckland preferred an alliance with the Sikhs over an alliance with Afghanistan, with far too much mutual enmity between the two to ally with both at the same time; and after Dost Mohammed Khan invited Count Witkiewicz to Kabul (as a way to frighten the British into making an alliance with him against his archenemy Ranjit Singh, not because he really wanted an alliance with Russia- believing that only the British had the power to compel Singh to return the former Afghan territories he had conquered, whereas the Russians did not), his political advisers exaggerated the threat, with the resulting diplomatic fallout ultimately resulting in the issuing of the Simla Declaration, which condemned Dost Mohammed Khan for making "an unprovoked attack on the empire of our ancient ally, Maharaja Ranjit Singh", and effectively declared war on the Sikhs' behalf.

ITTL, relations between the Sikhs and British would likely take a bit of a hit initially, but the Dal Khalsa would most likely be perceived as being even more formidable in the eyes of Lord Auckland and the British, with the BEIC even less likely to favor an alliance with Afghanistan over an alliance with the Sikhs after having been deprived of a direct border between Afghanistan's territories and its own by the Sikhs' acquisition of Shikarpur and control over access to the Bolan Pass ITTL. The British envoy, Alexander Burnes, was only dispatched by the company to Kabul on their political mission to form an alliance with Amir Dost Mohammad Khan against Russia in 1836 IOTL, after having successfully coordinated the Rupur Summit (the first meeting of Maharaja Ranjit Singh with a sitting commander of British forces in India, Governor General Lord William Bentinck) in Oct 1831, with his and Henry Pottinger's surveys of the Indus river on that visit having prepared the way for a future assault on the Sindh to clear a path towards Central Asia. ITTL though, any attempts to clear said path via the Sindh have been stymied by the Sikhs getting there first; would he still even be granted permission at Ludhiana to proceed on his political mission to Dost Mohammed Khan at Kabul ITTL? And even if he is, Burnes advised Lord Auckland to support Dost Mohammed on the throne of Kabul, but the viceroy preferred to follow the opinion of Sir William Hay Macnaghten and attempt to reinstate Shah Shuja instead IOTL; ITTL, without the pivotal role he played in facilitating the British conquest of Sindh, wouldn't Auckland be even less likely to listen to his advice, and support the reinstatement of Shah Shuja over Dost Mohammed Khan?

And without Sindh in British hands, Eldred Pottinger (John Pottinger's nephew) probably never makes it into Herat, via the Bolan Pass as he did IOTL, in time to be in the city and appointed in a full advisory role prior to the Siege of Herat. Without him there to assist in shoring up its defences, Herat's a lot more likely to fall to the Russian-backed Qajar Dynasty of Persia in the months prior to the lifting of said siege IOTL (with Polish General Isidor Borowski, who'd played a pivotal role in the modernization of the Iranian army, also markedly likelier to survive his assault on the markedly weaker fortifications there). And if Herat does fall, and 'Eastern Khorasan' is recaptured by Qajar Iran at this juncture, then the Sikh Empire'd basically be the BEIC's last remaining meaningful buffer state against a potentially imminent Persian and/or Russian invasion of India. Would the British be willing to risk jeopardizing that, and undermining the Sikh Empire's integrity, after that point?

Jackson Lennock

Well-known member

Does Herat falling necessarily mean that Kabul falls as well?

A map like this seems plenty possible. Qajar Persia controls most of Balochistan and Herat, but the Emirate of Afghanistan would still stand.

Looking at a topographical map - it seems plenty possible that Herat and Afghan Balochistan would be the extent of Qajar Persia's advance. I suppose Kandahar and Quetta would be areas the Qajar dynasty could try for though.

A map like this seems plenty possible. Qajar Persia controls most of Balochistan and Herat, but the Emirate of Afghanistan would still stand.

Looking at a topographical map - it seems plenty possible that Herat and Afghan Balochistan would be the extent of Qajar Persia's advance. I suppose Kandahar and Quetta would be areas the Qajar dynasty could try for though.

In this sort of scenario though, you wouldn't expect the British to be happy about Qajar Persia, especially one that's more closely aligned with the Russians than IOTL, controlling as much of Balochistan as it does on that map; no way they'd be content settling for just the port city of Gwadar, as an isolated enclave on its own, when they have clear naval superiority, when Oman's been its de-facto vassal state since 1800, and when the map of the Sultanate of Oman's control at the time looked like this, thanks to a lease agreement with Persia whereby they controlled the coastal stretch of some 100 miles from Sadij to Khamir, and inland about 30 miles, as far as Shamil, as well as controlling the islands of Hormuz and Qeshm.Does Herat falling necessarily mean that Kabul falls as well?

A map like this seems plenty possible. Qajar Persia controls most of Balochistan and Herat, but the Emirate of Afghanistan would still stand.

View attachment 52219

Looking at a topographical map - it seems plenty possible that Herat and Afghan Balochistan would be the extent of Qajar Persia's advance. I suppose Kandahar and Quetta would be areas the Qajar dynasty could try for though.

View attachment 52220

The Persians attempted to oust the Omanis in 1823, but the sultan managed to keep his hold on Bandar through bribery and tribute of the governor of Shiraz; whilst in 1845–46, an army under the governor-general of Fars menaced Bandar to extort tribute, while another army under the governor of Kerman besieged Minab. The Omanis threatened to blockade Persia, but the British resident at Bushir convinced them to back down. The Persians recovered the city of Bandar Abbas in 1854, while the sultan was in Zanzibar; but under British pressure following the Anglo-Persian War in 1856, Persia renewed Oman's lease on favorable terms, before they finally revoked it in 1868, citing a clause which permitted its termination if the sultan of Oman were overthrown.

IOTL, when the British received word of the Siege of Herat, realising the impracticality of sending a force across Afghanistan (which would be entirely impossible ITTL), they sent a naval expedition to the Persian Gulf and on June 19, 1838 occupied Kharg Island, only returning it after the Persians backed down and lifted the siege. If the Persians have already taken Herat though, and refuse to return it, would the British return Kharg Island, or retain it? And what of the rest of the strip under Oman's nominal authority, whose foreign affairs are controlled entirely by the British? A map like that does seem possible, but it'd have to involve the British screwing up badly enough to lose all of that (whilst still somehow managing to hold onto Gwadar alone), or agreeing to let it all go back to Persia. And rather than the Khanate of Kalat being conquered in its entirety by Qajar Persia, I think you'd most likely see a divide similar to this, with a reduced Kalat actively seeking protectorate status either from the British or its new eastern neighbor after receiving word of the losses of Makran, Kharan and the Chagai regions, and being more likely than not to get it (with all of its territory being too vast, inhospitable and lacking in transport infrastructure for the Persians, or anyone else, to have a chance of conquering it all in a single campaign):

So a map like that first one does seem fairly possible, though if it were my TL, I'd change the colors of Bahawalpur, rump-remnant Kalat (as shown above), and Eastern Sindh as well, to pale lavender, reflecting their status. IMHO though, the British'd really have to drop the ball not to at least attempt to hold onto and reinforce at least the most strategically important of the Sultanate of Oman's pre-existing holdings north of the Strait of Hormuz in this scenario, centered around Bandar Abbas. At least, that's how I reckon the map'd look like c.1850 ITTL. Though there'd be plenty of time and room for plenty of changes to the map after that point...

BTW, another thing worth mentioning, with regards to what a Sikh Empire with access to a deep sea port and marine trade would do with it; Maharajah Ranjit Singh prioritized the development of the river trade network, which became increasingly important over the course of his reign, to the detriment of modernizing and developing the road network. Having inherited the Mughal-era Karkhana system, which years of Afghan terror had brought to a halt, he immediately handed all state-owned Karkhanas ('workshops' or 'store houses') over to Fakir Azizuddin for management; who set about attempting to modernize them. Those Karkhanas deemed to be critical establishments, connected to the military, remained in state control, and each had a European entasked with managing it, as its 'Darogah', with the goal of disseminating their skills to their employees, whilst those in sectors such as textiles, leather, wooden goods, pottery and paper-making remained in private hands (typically, those of members of the newly-emerging Sikh aristocracy, paralleling the founding and growth of Zaibatsu conglomerates in Japan). And new Karkhanas being established as required, the largest of which were created in Lahore, Multan, Amritsar, Leiah (Layyah) and Shujabad, with political stability and security playing a crucial role in providing an enabling environment.

All officials were strictly instructed to assist traders and manufacturers, with the major port of Lahore further transporting goods onto the rivers from the inland portions of the Sikh Empire's heartland, the Bari Doab. And one of the primary reasons for General Ventura's rapid accumulation of power and influence, to the extent that he swiftly overtook his formal senior and leader General Allard as the unofficial leader of the Fauj-i-Khas and of the 'French Brigade' in the Sikh Court, was the wealth which he garnered after being installed as the Darogah of a shipping Karkhana in the early 1830s, on account of his prior experience as a ship-broker in Constantinople (where he'd been forced to change his name from Rubino to Jean-Baptiste to hide his Jewish origins)- assigned to manufacture steam boats to carry goods and products up and down the rivers, as well as to negotiate deals with the buyers and charterers of these boats. And with this Karkana under his effective control, Ventura rapidly became the richest and most influential European in the Sikh Empire.

He lived in style in a modest residence known as Anarkali House, combining European and Persian architectural elements, and decorated with Persian and Kashmiri rugs of great beauty strewn on the floors, which he built on the ruins of a Mughal palace, in close proximity to the Tomb of Anarkali (which was itself converted into a residence for his Armenian wife Anna Moses, whom he'd married in Ludhiana, and their only child, his daughter Victorine Ventura), surrounded by a garden known as Anarkali Garden, where he was typically given the honour of receiving foreign dignitaries, especially Europeans, visiting the Sikh court; with the traveler Baron Charles von Hügel, upon his visit to Lahore in 1836, remarking that "General Ventura's house, built by himself, though of no great size, combines the splendor of the east with the comforts of European residence". And this is still in use today, largely unchanged- acquired from Ventura (who'd by that stage abandoned the Punjab, along with the rest of the 'French Brigade', after Maharajah Sher Singh's assassination; returning to Europe and taking up residence in Paris, where he subsequently lost most of the fortune he'd amassed in unsuccessful commercial enterprises) by the British, his residence became the British Residency after the First Anglo-Sikh War, being moderately extended and becoming the Secretariat of the Government of the Punjab in 1871, with the building still serving as the office of the Chief Secretary of the Punjab in Pakistan to this day.

Kashmiri shawls and textiles were very much in vogue back in Europe, and whilst William Moorcroft's study of their manufacture, during his year-long stay there in 1822, had disseminated many of their patterns such as the 'Paisley' design back to Europe to be manufactured there, they were still very much the height of fashion culture there, in France and in Paris in particular. And whilst the British East India Company dominated the maritime trade between India and Europe, Ventura's Karkhana granted him a near-monopoly over the river trade in Kashmir shawls, and all other Punjabi exports of note, from the Sikh Empire to the British East India Company via Ludhiana and the European export market- earning the title/nickname of 'Count de Mandi', by which he was generally known in France and the UK after going on a diplomatic mission to Paris and London in 1837 (but being recalled to Lahore in 1838 before he had time to visit his family back in Italy), not after the eponymous Rajahnate of Mandi (with Ventura only commanding a campaign in the Simla Hill States several years later, in 1841) but as a pun to reflect his role as a trade broker, with Mandi translating as 'Market'.

And Ventura also sought to remedy Maharajah Ranjit Singh's blind spot, with regard to building better roads and increasing returns on investment by improving labor mobility; employing a fellow Italian, Jules Bianchi, in 1835 as a road engineer, who proved himself by constructing a road from General Ventura's house to the Fort in Lahore (Lahore's famous Mall Road, which the British would later establish Lahore's most prominent government institutions and commercial enterprises along the flanks of under their rule, and still serves as the epicentre of Lahore's civil administration, as well as one of its most fashionable commercial areas, to this day). Bianchi was then entrusted with the task of building a ring road encircling the walled city of Lahore, with a purview to carrying out other road-laying projects- but was struck down with a severe illness which rendered him incapable of carrying out this task, and killed him before he could return to Italy. The next skilled road engineer who arrived at the Sikh Court would be Rossaix, a Frenchman whom he had served alongside in Napoleon's army, but he only came to the Punjab to take up service under the Sikh Maharaja Sher Singh in 1843, having declined Ventura's earlier invites due to the ongoing political strife and intrigues in Lahore. His main charge was the construction of bridges and laying out of roads; but as with Ventura, Court and the other Europeans of the 'French Brigade', he left after Sher Singh's assassination, leaving his assigned task largely untouched, and died in 1844, less than a year later.

So then, one does have to wonder just how much more wealth, power and influence Ventura would have wound up amassing in this timeline, with Sindh falling into Sikh hands, thereby giving the Sikh Imperial state-owned shipping Karkhana that'd been placed under his management free access directly to the European market, via the seaports of Thatta and Karachi, without needing to go through the BEIC as intermediaries? Could it have the potential to be expanded into an international merchant shipping/trading company, analogous to, and potentially markedly more powerful and impactful than, the Mitsubishi Group's Nippon Yusen; but remaining under state ownership of the Sikh Empire, and well-placed to expand its operations and go international a full 50 years earlier than the Japanese Nippon Yusen company (which only expanded its operations beyond the Sea of Japan to go international in the 1890s IOTL)? Or even failing that, to provide the catalyst for private steamship companies to be established in the Sikh Empire in the following decades, paralleling the formation of Nippon Yusen in Imperial Meiji-era Japan? Could we even see a Sikh Trading Company, or Companies, emerging, and embarking upon colonial ventures of their own...?

All officials were strictly instructed to assist traders and manufacturers, with the major port of Lahore further transporting goods onto the rivers from the inland portions of the Sikh Empire's heartland, the Bari Doab. And one of the primary reasons for General Ventura's rapid accumulation of power and influence, to the extent that he swiftly overtook his formal senior and leader General Allard as the unofficial leader of the Fauj-i-Khas and of the 'French Brigade' in the Sikh Court, was the wealth which he garnered after being installed as the Darogah of a shipping Karkhana in the early 1830s, on account of his prior experience as a ship-broker in Constantinople (where he'd been forced to change his name from Rubino to Jean-Baptiste to hide his Jewish origins)- assigned to manufacture steam boats to carry goods and products up and down the rivers, as well as to negotiate deals with the buyers and charterers of these boats. And with this Karkana under his effective control, Ventura rapidly became the richest and most influential European in the Sikh Empire.

He lived in style in a modest residence known as Anarkali House, combining European and Persian architectural elements, and decorated with Persian and Kashmiri rugs of great beauty strewn on the floors, which he built on the ruins of a Mughal palace, in close proximity to the Tomb of Anarkali (which was itself converted into a residence for his Armenian wife Anna Moses, whom he'd married in Ludhiana, and their only child, his daughter Victorine Ventura), surrounded by a garden known as Anarkali Garden, where he was typically given the honour of receiving foreign dignitaries, especially Europeans, visiting the Sikh court; with the traveler Baron Charles von Hügel, upon his visit to Lahore in 1836, remarking that "General Ventura's house, built by himself, though of no great size, combines the splendor of the east with the comforts of European residence". And this is still in use today, largely unchanged- acquired from Ventura (who'd by that stage abandoned the Punjab, along with the rest of the 'French Brigade', after Maharajah Sher Singh's assassination; returning to Europe and taking up residence in Paris, where he subsequently lost most of the fortune he'd amassed in unsuccessful commercial enterprises) by the British, his residence became the British Residency after the First Anglo-Sikh War, being moderately extended and becoming the Secretariat of the Government of the Punjab in 1871, with the building still serving as the office of the Chief Secretary of the Punjab in Pakistan to this day.

Kashmiri shawls and textiles were very much in vogue back in Europe, and whilst William Moorcroft's study of their manufacture, during his year-long stay there in 1822, had disseminated many of their patterns such as the 'Paisley' design back to Europe to be manufactured there, they were still very much the height of fashion culture there, in France and in Paris in particular. And whilst the British East India Company dominated the maritime trade between India and Europe, Ventura's Karkhana granted him a near-monopoly over the river trade in Kashmir shawls, and all other Punjabi exports of note, from the Sikh Empire to the British East India Company via Ludhiana and the European export market- earning the title/nickname of 'Count de Mandi', by which he was generally known in France and the UK after going on a diplomatic mission to Paris and London in 1837 (but being recalled to Lahore in 1838 before he had time to visit his family back in Italy), not after the eponymous Rajahnate of Mandi (with Ventura only commanding a campaign in the Simla Hill States several years later, in 1841) but as a pun to reflect his role as a trade broker, with Mandi translating as 'Market'.

And Ventura also sought to remedy Maharajah Ranjit Singh's blind spot, with regard to building better roads and increasing returns on investment by improving labor mobility; employing a fellow Italian, Jules Bianchi, in 1835 as a road engineer, who proved himself by constructing a road from General Ventura's house to the Fort in Lahore (Lahore's famous Mall Road, which the British would later establish Lahore's most prominent government institutions and commercial enterprises along the flanks of under their rule, and still serves as the epicentre of Lahore's civil administration, as well as one of its most fashionable commercial areas, to this day). Bianchi was then entrusted with the task of building a ring road encircling the walled city of Lahore, with a purview to carrying out other road-laying projects- but was struck down with a severe illness which rendered him incapable of carrying out this task, and killed him before he could return to Italy. The next skilled road engineer who arrived at the Sikh Court would be Rossaix, a Frenchman whom he had served alongside in Napoleon's army, but he only came to the Punjab to take up service under the Sikh Maharaja Sher Singh in 1843, having declined Ventura's earlier invites due to the ongoing political strife and intrigues in Lahore. His main charge was the construction of bridges and laying out of roads; but as with Ventura, Court and the other Europeans of the 'French Brigade', he left after Sher Singh's assassination, leaving his assigned task largely untouched, and died in 1844, less than a year later.

So then, one does have to wonder just how much more wealth, power and influence Ventura would have wound up amassing in this timeline, with Sindh falling into Sikh hands, thereby giving the Sikh Imperial state-owned shipping Karkhana that'd been placed under his management free access directly to the European market, via the seaports of Thatta and Karachi, without needing to go through the BEIC as intermediaries? Could it have the potential to be expanded into an international merchant shipping/trading company, analogous to, and potentially markedly more powerful and impactful than, the Mitsubishi Group's Nippon Yusen; but remaining under state ownership of the Sikh Empire, and well-placed to expand its operations and go international a full 50 years earlier than the Japanese Nippon Yusen company (which only expanded its operations beyond the Sea of Japan to go international in the 1890s IOTL)? Or even failing that, to provide the catalyst for private steamship companies to be established in the Sikh Empire in the following decades, paralleling the formation of Nippon Yusen in Imperial Meiji-era Japan? Could we even see a Sikh Trading Company, or Companies, emerging, and embarking upon colonial ventures of their own...?

Last edited:

BTW, I'm planning on expanding upon this WI Scenario to write a proper ATL (albeit in more of a TLIAW, alternate historical textbook sort of format than as a proper character-orientated AH novel); thanks to some of the feedback earlier in this thread, I've more or less got the events of the 'first phase' plotted out, from the POD in late 1830 up until roughly the mid-1840's. I was wondering though, how much of an impact might a seafaring Sikh Empire, and the start of the dissemination of Sikh cultural, religious and social practices to the rest of the world, have elsewhere?

In addition to the Imperial Sikh steamboat manufacturing Karkhana, the Sikh Labanas/Banjaras would almost certainly be set to play a major role, perhaps even the leading role, in the Sikh Empire's maritime trade activities. IOTL, they were stripped of their livelihoods and forced into poverty by the BEIC cornering them out of the market, as had already happened across the rest of British-controlled India (with the Company and the British ships contracted by them given a monopoly on all international trade routes, and duties imposed upon any Indian merchant ships moving to and from ports in British India as well as foreign ones, and an act imposed in Parliament to ban any Indian-built or Indian-crewed ships from being deemed 'British-registered vessels', thus blocking them from foreign ports). Forced to settle down as agriculturalists under British rule, having been condemned as a 'criminal tribe' for their resemblance to the Romani Gypsies (with evidence now indicating that this does have a basis in fact, with genomic studies confirming that the Romani peoples have the closest affinity to the Labana of Punjab, and linguistic studies identifying Lubanki as the likeliest 'sister language' of Romani), they were effectively driven to cultural extinction IOTL, to the extent that their creole language, Lubanki, was rendered extinct before the turn of the 20th century (with the Rajasthani dialect/language of Lambadi being the closest to have survived, and the Gor-boli macrolanguage, like Romani, having had several varieties divergent enough to be considered languages of their own).

However, the Labana of the Punjab region, were among the earliest, most evangelical and enthusiastic groups to have been mass-converted to Sikhism, having become almost universally Sikh even before the foundation of the Khalsa; with Bhai Dasa Labana having purportedly been appointed as the Masand (Sikh community leaders who lived far from the Guru, but acted to lead the distant congregations, their mutual interactions and collect revenue for Sikh activities and temple building- with the Manji system being conceptually similar in its aims, and similarly important in Sikh missionary activity, to the diocese system in Christianity) for the entirety of Africa by Guru Ram Das (the 4th Guru). The position of Masand was effectively hereditary and patrilineal (though and in an attempt to reform the Manji system and promote gender equality by Guru Har Rai (the 7th Guru), the system was also created to teaching Sikh religion to women, via an equivalent hereditary matrilineal position of Pirii), and Bhai Dasa's direct lineage and familial relatives (which also included Bhai Lakhi Rai Banjara, via marital ties, and his descendants) played pivotal roles in the history of Sikhism and the Sikh Confederacy. His son, Makhan Shah Labana, possessed a significant merchant fleet, trading in spices, Bengali silk, Kashmiri shawls and other commodities beyond Egypt into the Mediterranean as far afield as Portugal, and after having identified and proclaimed Guru Tegh Bahadur as the ninth Guru of Sikhism, had been the first major preacher of Sikhism abroad, beyond India.

In the era of Sikh rule, the Labana were counted among the highest echelons of society, with close ties between them and several of the Sikh misls (the Bhangi Misl in particular, with Bhai Lakhi Rai Banjara's grandsons having been closely involved with and fought alongside its founder, Banda Singh Bahadur's appointed successor Sardar Chhajja Singh, along with the Sukerchakia and Nakai Misls) with their largest and most populous Tanda (literally 'place of settlement', where the otherwise nomadic Labana would settle each year in fixed village accommodations during the monsoon months, and where their elderly would settle down permanently after retirement) situated at Gujrat, along the banks of the Chenab River, where it formed the point where the Sukerchakia and Bhangi Misls bordered one another. The Sikh Labanas of Punjab were by far the best educated and most literate of the Banjara groups in India as well, as well as the most progressive when it came to women's rights. And in the case of a surviving Sikh Empire, giving the Labana (along with any members of the other Banjara communities from all the other coastal provinces of British India- the majority of whom had already been, and could to this day still be considered, 'Nanakpathis'- if they want to escape the BEIC's draconian restrictions, persecution and social stigmatization, avoid inevitable bankruptcy, and continue their way of life, by emigrating over to the Indus River Delta instead) the freedom and capacity to manage and conduct their own maritime trade with the rest of the world via Sindh including even Europe itself, one can only speculate on the potential repercussions farther afield.

Particularly given that the Sikh Labanas also had their sworn mission, which their most influential and respected family clan in the Punjab been entasked with carrying out by Guru Ram Das personally over 150yrs prior to the POD (in the late 16th century), to spread the word of Sikhism abroad, and to the peoples of Africa in particular. As well as the fact that their language, which would almost certainly be written and see continued use ITTL (with an outside chance of Lubanki even becoming the lingua franca for late Indian maritime trade), was also the closest to the Romani language group, to the extent that there's a better than 50-50 chance that Lubanki and Romani speakers would've been borderline mutually intelligible to one another. Might we even see the Sikhs emerging as a dark horse ITTL in the 'Scramble for Africa', and/or Romani people in the rest of the world converting to Sikhi (or adopting elements of Sikh culture) after reconnecting with the Labana merchants of the Sikh Empire, in enough numbers to become significant and start affecting the religious landscape over in the New World and Europe in the early 20th century, even without factoring in the possibility of large-scale emigration from the Sikh Empire's (contiguous) territories?

In addition to the Imperial Sikh steamboat manufacturing Karkhana, the Sikh Labanas/Banjaras would almost certainly be set to play a major role, perhaps even the leading role, in the Sikh Empire's maritime trade activities. IOTL, they were stripped of their livelihoods and forced into poverty by the BEIC cornering them out of the market, as had already happened across the rest of British-controlled India (with the Company and the British ships contracted by them given a monopoly on all international trade routes, and duties imposed upon any Indian merchant ships moving to and from ports in British India as well as foreign ones, and an act imposed in Parliament to ban any Indian-built or Indian-crewed ships from being deemed 'British-registered vessels', thus blocking them from foreign ports). Forced to settle down as agriculturalists under British rule, having been condemned as a 'criminal tribe' for their resemblance to the Romani Gypsies (with evidence now indicating that this does have a basis in fact, with genomic studies confirming that the Romani peoples have the closest affinity to the Labana of Punjab, and linguistic studies identifying Lubanki as the likeliest 'sister language' of Romani), they were effectively driven to cultural extinction IOTL, to the extent that their creole language, Lubanki, was rendered extinct before the turn of the 20th century (with the Rajasthani dialect/language of Lambadi being the closest to have survived, and the Gor-boli macrolanguage, like Romani, having had several varieties divergent enough to be considered languages of their own).

However, the Labana of the Punjab region, were among the earliest, most evangelical and enthusiastic groups to have been mass-converted to Sikhism, having become almost universally Sikh even before the foundation of the Khalsa; with Bhai Dasa Labana having purportedly been appointed as the Masand (Sikh community leaders who lived far from the Guru, but acted to lead the distant congregations, their mutual interactions and collect revenue for Sikh activities and temple building- with the Manji system being conceptually similar in its aims, and similarly important in Sikh missionary activity, to the diocese system in Christianity) for the entirety of Africa by Guru Ram Das (the 4th Guru). The position of Masand was effectively hereditary and patrilineal (though and in an attempt to reform the Manji system and promote gender equality by Guru Har Rai (the 7th Guru), the system was also created to teaching Sikh religion to women, via an equivalent hereditary matrilineal position of Pirii), and Bhai Dasa's direct lineage and familial relatives (which also included Bhai Lakhi Rai Banjara, via marital ties, and his descendants) played pivotal roles in the history of Sikhism and the Sikh Confederacy. His son, Makhan Shah Labana, possessed a significant merchant fleet, trading in spices, Bengali silk, Kashmiri shawls and other commodities beyond Egypt into the Mediterranean as far afield as Portugal, and after having identified and proclaimed Guru Tegh Bahadur as the ninth Guru of Sikhism, had been the first major preacher of Sikhism abroad, beyond India.

In the era of Sikh rule, the Labana were counted among the highest echelons of society, with close ties between them and several of the Sikh misls (the Bhangi Misl in particular, with Bhai Lakhi Rai Banjara's grandsons having been closely involved with and fought alongside its founder, Banda Singh Bahadur's appointed successor Sardar Chhajja Singh, along with the Sukerchakia and Nakai Misls) with their largest and most populous Tanda (literally 'place of settlement', where the otherwise nomadic Labana would settle each year in fixed village accommodations during the monsoon months, and where their elderly would settle down permanently after retirement) situated at Gujrat, along the banks of the Chenab River, where it formed the point where the Sukerchakia and Bhangi Misls bordered one another. The Sikh Labanas of Punjab were by far the best educated and most literate of the Banjara groups in India as well, as well as the most progressive when it came to women's rights. And in the case of a surviving Sikh Empire, giving the Labana (along with any members of the other Banjara communities from all the other coastal provinces of British India- the majority of whom had already been, and could to this day still be considered, 'Nanakpathis'- if they want to escape the BEIC's draconian restrictions, persecution and social stigmatization, avoid inevitable bankruptcy, and continue their way of life, by emigrating over to the Indus River Delta instead) the freedom and capacity to manage and conduct their own maritime trade with the rest of the world via Sindh including even Europe itself, one can only speculate on the potential repercussions farther afield.

Particularly given that the Sikh Labanas also had their sworn mission, which their most influential and respected family clan in the Punjab been entasked with carrying out by Guru Ram Das personally over 150yrs prior to the POD (in the late 16th century), to spread the word of Sikhism abroad, and to the peoples of Africa in particular. As well as the fact that their language, which would almost certainly be written and see continued use ITTL (with an outside chance of Lubanki even becoming the lingua franca for late Indian maritime trade), was also the closest to the Romani language group, to the extent that there's a better than 50-50 chance that Lubanki and Romani speakers would've been borderline mutually intelligible to one another. Might we even see the Sikhs emerging as a dark horse ITTL in the 'Scramble for Africa', and/or Romani people in the rest of the world converting to Sikhi (or adopting elements of Sikh culture) after reconnecting with the Labana merchants of the Sikh Empire, in enough numbers to become significant and start affecting the religious landscape over in the New World and Europe in the early 20th century, even without factoring in the possibility of large-scale emigration from the Sikh Empire's (contiguous) territories?

Jackson Lennock

Well-known member

Certainly one of the more plausible outcomes; especially if Maharajah Ranjit Singh's successors decide to maintain amiable relations with the British, favoring consolidation over conducting any further wars with its neighbors. Maharajah Kharak Singh, in particular, was purportedly thus inclined (being a supporter and follower of the most pacifistic sect of Sikhism), and sought to maintain good relations with the British. Nau Nihal Singh, though, was markedly more jingoistic, as were the majority of the senior generals in the Sikh Army. And the Commander-in-chief of the Sikh Army especially, Hari Singh Nalwa, certainly wouldn't be content with those north-western borders- they'd mean that his own efforts to conquer Hazara had all been in vain, and that Afghanistan had been freely allowed to reunify, in spite of the weakening of Afghan rule in Kabul having already seen the majority of its governors declare their own independence, and the Afghan state having already effectively been balkanized before reunification and consolidation under Dost Mohammad Khan's rule IOTL.Perhaps this map?

The Qajars conquer Herat, but the British refuse to leave Bandar Abbas, Kharga, or Gwadar. The Balochi Khanates seek British protection, and Britain later takes the bulk of Qajar Balochistan.

View attachment 65644

During the early years of his first reign though, Dost Mohammad Khan's influence was generally confined to Kabul and Ghazni. In the 1820s, the Kabul realm under the Barakzais' authority ended just twenty miles south of Kabul, whilst the base of the Hindu Kush formed the northern boundary of his realm until 1826, when a rebellious brother of his, named Habibullah, controlled Parwan with a force of Uzbeks and Hazaras. Although Dost Mohammad controlled Bamyan, the routes leading there were controlled by independent Hazara chiefdoms. In the east of his realm, the extent of his rule ended at Jagdalak pass, while Jalalabad and Laghman remained under the control of Muhammad Zaman Khan and Abd-Al-Jabbar Khan respectively. And despite Ghazni being a part of Dost Mohammad's sphere of influence, Amir Muhammad exercised direct control over the city, with it being unknown if he ever submitted revenue payments to Dost Mohammad. All these combined made the early Muhammadzai Kingdom surely possibly doomed to fail, having been isolated directly by most of the other powers of Afghanistan, and drawn into conflict with others occasionally, alongside nominal discontent- including amongst his brothers, who were seeking to fight for rule over Kabul- the early Muhammadzai Kingdom appeared as if it would not fare well.

But that all began to change in early 1834, when Shah Shuja, the former Durrani ruler of Afghanistan, began approaching Kandahar, as the Dil brothers appeased to Dost Mohammad for assistance against Shah Shuja. Rather than mobilizing his forces toward Kandahar as promised though, Dost Mohammad led his forces eastwards to Siyahsang instead, with his sons Mohammad Akram Khan and Muhammad Akbar Khan sent to Jalalabad, where they "scattered" the army of Muhammad Zaman Khan, on an attack which was justified under the claimed pretext of raising an army to combat Shah Shuja. Following this, Dost lead his forces to Jagdalak (controlling the Lataband Pass), which was ruled by Muhammad Usman Khan under Zaman Khan. Immediately as Dost Mohammad fielded his armies outside the city, Usman Khan surrendered the city to Dost, under the condition that the city would be spared from a military attack. With Dost Mohammad having now attempted to seize Jalalabad, Zaman Khan entered negotiations with Sultan Mohammad Khan to support him in case of another attack from Dost in Kabul. However, Sultan Mohammad Khan was unable to provide any aid to Zaman, since Peshawar had been weakened far too much in the past few years (both under the rule of Barelvi's 'Islamic State', and in its subsequent re-pacification by the Sikhs).

Only supported by local chiefs, Zaman Khan found himself unable to field a proper army to contest Dost Mohammad as he marched on Jalalabad. Dost Mohammad seized the city, but offered generous and honorable peace terms, one of which was that he'd compensate Zaman Khan with over 150,000 rupees per year for his annexed territories. Having now secured Jalalabad, Dost Mohammad appointed Muhammad Akram Khan and Amir Muhammad Khan as governors of the city. The Province of Jalalabad under Dost's rule extended as far as Dakka in Mohmand territory from the Jagdalak pass. The province of Jalalabad alone and the villages of Lagman fielded over 400,000 rupees of revenue, and following Dost Mohammad's conquest, it raised to around 465,000 rupees. Followed by this conquest, many new regions became subject to Dost Mohammad, including the valley of Kunar, where the governor was appointed by Dost Mohammad Khan in exchange for tribute. Dost Mohammad then marched on Kandahar in 1834, having exploited the situation at hand to gain more influence over Kandahar. Shah Shuja set out in the summer of 1834 to Kandahar, having already routed the armies of the Talpurs of Sindh and reclaimed Shikarpur for himself; but this expedition was a failure, as Shah Shuja's siege ended in only 54 days, with Shah Shuja's army being defeated in early July by the joint coalition between Dost Mohammad Khan and the rulers of Kandahar.

In this scenario though, how much would all of that change? Haven't quite got round to posting the pertinent part of the TL I started working on (which would be Chapter 6, with at least one or two interludes to go between the point I've gotten to and that point), but gave up on posting due to lack of interest. But in my take on it, the repercussions of Barelvi's earlier death, and the completed conquest of Shikarpur by the Sikhs already by 1831, were also set to have pretty significant cascade effects on Shah Shuja's pending expedition, which would in turn also greatly alter how things pan out in the ongoing 'Barakzai Civil War'.

After all, ITTL, the army of Peshawar, under the command of ʿAbd al-Rasul Khan (son of Sardar Rahimdad Khan, and husband to Sardar Dost Muhammad Khan’s sister) and trained by the Russian adventurer Vieskenawitch (who'd previously been employed by Shah Abbas Mirza)- which Sultan Muhammad Khan had sent out to do battle with Barelvi's Muhammadiyan Order IOTL, only for them to be routed after ʿAbd al-Rasul was killed in the resulting battle, with Sultan Muhammad Khan subsequently fleeing the city with his retinue, being granted sanctuary by the Sikhs (though he continued to govern the southern portion of the province of Peshawar, from the city of Kohat instead), whilst Barelvi and the Muhammadiyans' forces subsequently marched into and conquered the city of Peshawar largely unopposed in early 1830, filling the power vacuum left behind after Sultan Muhammad Khan's flight to establish their short-lived 'Islamic Caliphate of the Peshawar'- is still very much intact, leaving Sultan Muhammad Khan's grasp on power as the ruler of Peshawar no less tenuous than those of the Nawab of Bahawalpur, or the fellow Barakzai rulers of Jalalabad and Kandahar.

Shah Shuja has no choice but to go through the passages now controlled by the Sikhs, unless he's willing to wait until the British consolidate their own control further long enough to think about going in to seize Kandahar for himself via the Balochi Khanates. If Dost Mohammad Khan still follows the course of action he did IOTL, leading his forces eastwards to Jalalabad to conquer Muhammad Zaman Khan's territories first,with Zaman Khan even likelier to enter negotiations with Sultan Mohammad Khan to support him against Dost Mohammad Khan's forces, Sultan Mohammad Khan WOULD be able to provide that support, and dispatch a proper army against Dost Mohammad's march on Jalalabad. And if said coalition's army met the same fate it did against Barelvi's forces regardless, then the Sikhs'd likely obtain Muhammad Zaman Khan's vassalage as well, with the Province of Jalalabad a lot more likely to then also fall under the Sikhs' sphere of influence in the same manner.

Especially if Shah Shuja and his mercenary force is still allowed free passage via Sikh territory and the Bolan Pass to march against Kandahar (a route which he only chose IOTL because Maharajah Ranjit Singh's demands in return for offering Shah Shuja passage through the Sikh Empire were too steep; refusing to let them through unless not only Peshawar, but Shikarpur and Jalalabad as well, were ceded in perpetuity to the Sikhs in exchange), with none of its own manpower, supplies or funds expended on their efforts to conquer and impose his dominion over the Talpurs or the territory of Shikarpur along the way. TBH, having only gotten about 5yrs or so into this TL from the original POD, I'm still not even sure if the Kingdom of Afghanistan's ultimately still going to exist 10yrs later ITTL. An awful lot of things just so happened to fall perfectly into place for Dost Mohammad Khan's kingdom to ultimately succeed in its reunification and consolidation IOTL. But since a bunch of those things have already unavoidably fallen out of place due to the POD in the adjacent territories, I don't know if it'd still be plausible for him to pull it off any more...

Last edited:

Ricardolindo

Well-known member

- Location

- Portugal

Great post.Certainly one of the more plausible outcomes; especially if Maharajah Ranjit Singh's successors decide to maintain amiable relations with the British, favoring consolidation over conducting any further wars with its neighbors. Maharajah Kharak Singh, in particular, was purportedly thus inclined (being a supporter and follower of the most pacifistic sect of Sikhism), and sought to maintain good relations with the British. Nau Nihal Singh, though, was markedly more jingoistic, as were the majority of the senior generals in the Sikh Army. And the Commander-in-chief of the Sikh Army especially, Hari Singh Nalwa, certainly wouldn't be content with those north-western borders- they'd mean that his own efforts to conquer Hazara had all been in vain, and that Afghanistan had been freely allowed to reunify, in spite of the weakening of Afghan rule in Kabul having already seen the majority of its governors declare their own independence, and the Afghan state having already effectively been balkanized before reunification and consolidation under Dost Mohammad Khan's rule IOTL.

During the early years of his first reign though, Dost Mohammad Khan's influence was generally confined to Kabul and Ghazni. In the 1820s, the Kabul realm under the Barakzais' authority ended just twenty miles south of Kabul, whilst the base of the Hindu Kush formed the northern boundary of his realm until 1826, when a rebellious brother of his, named Habibullah, controlled Parwan with a force of Uzbeks and Hazaras. Although Dost Mohammad controlled Bamyan, the routes leading there were controlled by independent Hazara chiefdoms. In the east of his realm, the extent of his rule ended at Jagdalak pass, while Jalalabad and Laghman remained under the control of Muhammad Zaman Khan and Abd-Al-Jabbar Khan respectively. And despite Ghazni being a part of Dost Mohammad's sphere of influence, Amir Muhammad exercised direct control over the city, with it being unknown if he ever submitted revenue payments to Dost Mohammad. All these combined made the early Muhammadzai Kingdom surely possibly doomed to fail, having been isolated directly by most of the other powers of Afghanistan, and drawn into conflict with others occasionally, alongside nominal discontent- including amongst his brothers, who were seeking to fight for rule over Kabul- the early Muhammadzai Kingdom appeared as if it would not fare well.

But that all began to change in early 1834, when Shah Shuja, the former Durrani ruler of Afghanistan, began approaching Kandahar, as the Dil brothers appeased to Dost Mohammad for assistance against Shah Shuja. Rather than mobilizing his forces toward Kandahar as promised though, Dost Mohammad led his forces eastwards to Siyahsang instead, with his sons Mohammad Akram Khan and Muhammad Akbar Khan sent to Jalalabad, where they "scattered" the army of Muhammad Zaman Khan, on an attack which was justified under the claimed pretext of raising an army to combat Shah Shuja. Following this, Dost lead his forces to Jagdalak (controlling the Lataband Pass), which was ruled by Muhammad Usman Khan under Zaman Khan. Immediately as Dost Mohammad fielded his armies outside the city, Usman Khan surrendered the city to Dost, under the condition that the city would be spared from a military attack. With Dost Mohammad having now attempted to seize Jalalabad, Zaman Khan entered negotiations with Sultan Mohammad Khan to support him in case of another attack from Dost in Kabul. However, Sultan Mohammad Khan was unable to provide any aid to Zaman, since Peshawar had been weakened far too much in the past few years (both under the rule of Barelvi's 'Islamic State', and in its subsequent re-pacification by the Sikhs).

Only supported by local chiefs, Zaman Khan found himself unable to field a proper army to contest Dost Mohammad as he marched on Jalalabad. Dost Mohammad seized the city, but offered generous and honorable peace terms, one of which was that he'd compensate Zaman Khan with over 150,000 rupees per year for his annexed territories. Having now secured Jalalabad, Dost Mohammad appointed Muhammad Akram Khan and Amir Muhammad Khan as governors of the city. The Province of Jalalabad under Dost's rule extended as far as Dakka in Mohmand territory from the Jagdalak pass. The province of Jalalabad alone and the villages of Lagman fielded over 400,000 rupees of revenue, and following Dost Mohammad's conquest, it raised to around 465,000 rupees. Followed by this conquest, many new regions became subject to Dost Mohammad, including the valley of Kunar, where the governor was appointed by Dost Mohammad Khan in exchange for tribute. Dost Mohammad then marched on Kandahar in 1834, having exploited the situation at hand to gain more influence over Kandahar. Shah Shuja set out in the summer of 1834 to Kandahar, having already routed the armies of the Talpurs of Sindh and reclaimed Shikarpur for himself; but this expedition was a failure, as Shah Shuja's siege ended in only 54 days, with Shah Shuja's army being defeated in early July by the joint coalition between Dost Mohammad Khan and the rulers of Kandahar.

In this scenario though, how much would all of that change? Haven't quite got round to posting the pertinent part of the TL I started working on (which would be Chapter 6, with at least one or two interludes to go between the point I've gotten to and that point), but gave up on posting due to lack of interest. But in my take on it, the repercussions of Barelvi's earlier death, and the completed conquest of Shikarpur by the Sikhs already by 1831, were also set to have pretty significant cascade effects on Shah Shuja's pending expedition, which would in turn also greatly alter how things pan out in the ongoing 'Barakzai Civil War'.

After all, ITTL, the army of Peshawar, under the command of ʿAbd al-Rasul Khan (son of Sardar Rahimdad Khan, and husband to Sardar Dost Muhammad Khan’s sister) and trained by the Russian adventurer Vieskenawitch (who'd previously been employed by Shah Abbas Mirza)- which Sultan Muhammad Khan had sent out to do battle with Barelvi's Muhammadiyan Order IOTL, only for them to be routed after ʿAbd al-Rasul was killed in the resulting battle, with Sultan Muhammad Khan subsequently fleeing the city with his retinue, being granted sanctuary by the Sikhs (though he continued to govern the southern portion of the province of Peshawar, from the city of Kohat instead), whilst Barelvi and the Muhammadiyans' forces subsequently marched into and conquered the city of Peshawar largely unopposed in early 1830, filling the power vacuum left behind after Sultan Muhammad Khan's flight to establish their short-lived 'Islamic Caliphate of the Peshawar'- is still very much intact, leaving Sultan Muhammad Khan's grasp on power as the ruler of Peshawar no less tenuous than those of the Nawab of Bahawalpur, or the fellow Barakzai rulers of Jalalabad and Kandahar.

Shah Shuja has no choice but to go through the passages now controlled by the Sikhs, unless he's willing to wait until the British consolidate their own control further long enough to think about going in to seize Kandahar for himself via the Balochi Khanates. If Dost Mohammad Khan still follows the course of action he did IOTL, leading his forces eastwards to Jalalabad to conquer Muhammad Zaman Khan's territories first,with Zaman Khan even likelier to enter negotiations with Sultan Mohammad Khan to support him against Dost Mohammad Khan's forces, Sultan Mohammad Khan WOULD be able to provide that support, and dispatch a proper army against Dost Mohammad's march on Jalalabad. And if said coalition's army met the same fate it did against Barelvi's forces regardless, then the Sikhs'd likely obtain Muhammad Zaman Khan's vassalage as well, with the Province of Jalalabad a lot more likely to then also fall under the Sikhs' sphere of influence in the same manner.

Especially if Shah Shuja and his mercenary force is still allowed free passage via the Bolan Pass to march against Kandahar, with none of its own manpower, supplies or funds expended on their efforts to conquer and impose his dominion over the Talpurs or the territory of Shikarpur along the way. TBH, having only gotten about 5yrs or so into this TL from the original POD, I'm still not even sure if the Kingdom of Afghanistan's ultimately still going to exist 10yrs later ITTL. An awful lot of things just so happened to fall perfectly into place for Dost Mohammad Khan's kingdom to ultimately succeed in its reunification and consolidation IOTL. But since a bunch of those things have already unavoidably fallen out of place due to the POD in the adjacent territories, I don't know if it'd still be plausible for him to pull it off any more...

Without British colonialism, how far do you think the Sikhs would be able to advance into Afghan territory? Most of what became the North-West Frontier Province was already under Sikh control when the British arrived. On the other hand, the British were never able to pacify the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and even Pakistan had minimal control there until the Afghan-Soviet War.

Jackson Lennock

Well-known member

Great post.

Without British colonialism, how far do you think the Sikhs would be able to advance into Afghan territory? Most of what became the North-West Frontier Province was already under Sikh control when the British arrived. On the other hand, the British were never able to pacify the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and even Pakistan had minimal control there until the Afghan-Soviet War.

Perhaps. Though I wasn't going to go for quite so much of a Sikh-wank (not for several decades after the POD, at any rate), on the grounds that attempting to consolidate and pacify all of that in one go would almost certainly leave the Sikh Empire over-extended, and make them far likelier to crumble if/when the British decide to try seizing their territories for their own. Afghanistan, in the 1820's to early '30s, was a patchwork quilt of petty chiefdoms and independent emirates, each governed by rulers who were constantly at war with one another. In this scenario, then Jalalabad becomes a lot more likely than not to fall into the Sikhs' possession too. After all, suzerainty over Jalalabad was the bare minimum which was demanded by Maharajah Ranjit Singh in exchange for granting Shah Shuja's passage to try and reclaim the throne of Afghanistan for his Durrani dynasty (having already ceded Peshawar in exchange for free passage for his previous attempt, which had already failed), and with Shikarpur and the access route via the Bolan Pass having already been seized for themselves by the Sikh Empire, Shah Shuja'd no longer have any choice but to accept those terms.So this? Assuming the Khan of Kalat becomes a vassal of the Sikhs and the Sikhs take Kandahar

View attachment 65653

Even without any of the losses incurred en route though, based upon his forces' strength and his distinctly inept, overly brutal leadership, even if Shah Shuja's likely capable of succeeding in besieging and restoring his dominion over the Principality of Qandahar's territories (minus those tributaries and dependencies that've already either broken away or been reduced to tributaries of the Sikhs, of course) at this attempt, I don't see him progressing much further into Afghanistan than that- with the most realistic end result at that point (in the mid-1830's) leaving Shah Shuja's Emirate of Kandahar, his nephew Kamran Shah's Emirate of Herat (if the Iranians haven't conquered it yet themselves, as they may well might ITTL, especially if Kamran Shah and Shah Shuja whittle down their forces' respective strength trying to conquer each other straight afterwards, as both had made no secret of their intentions to), and Dost Mohammad Khan's Emirate of Kabul as the primary powers of a permanently balkanized and divided Afghanistan (/or the 'Balkh' region of Greater Khorasan, if it does ultimately mostly fall back under Persian dominion).

But even so, I didn't see the Sikhs feasibly expanding any farther than Jalalabad in one go. And Jalalabad's about as far into Afghanistan as it'd be worthwhile for the Sikhs to advance into Afghan territory, and as they'd have a pretty good chance of placing under their control. Markedly more so, since the entirety of the watershed of the Chitral/Kunar River's ultimately accessible and controllable via this city- including Kunar and Nuristan, which was still known at this time as 'Kafiristan', with Walter Hamilton having reported in 1828 that the padishah of 'Cooner', who purportedly claimed direct descent from the Turk Shahis, was at the time joined in an alliance with the neighboring Kafirs (non Muslims) of Nuristan in an unending existential conflict against the Muslim invaders. Ultimately, this resistance eventually failed IOTL; 'Cooner'/Kunar fell in the late 1850's, with the 'Kafirs' who remained in Kafiristan being forcibly converted to Islam, on pain of death (in what undoubtedly consitituted an act of genocide) by Abdur Rahman Khan in the 1890's.

But one can imagine that, upon the Sikhs' entry to the region, both the Padishah of Kunar and the predominantly Hindu/Animist, still almost entirely non-Muslim 'Kafirs' would be pretty content and enthusiastic about the prospect of being brought under the protection of the Sikh Empire, and accepting the Maharajah of Lahore's suzerainty (rather than being forced to settle for the suzerainty of the similarly multi-ethnic and multi-religious, but far smaller and weaker state of Chitral, as they wound up being forced to settle for after Kunar and the Sikh Empire had both fallen IOTL- only to be ceded to the Amir of Afghanistan anyway, and freely allowed to be practically genocided out of existence, 40yrs later anyway). And this would making this particular region of 'Greater Kafiristan' by far the easiest part of Afghanistan in this era to permanently integrate into the Sikh Empire, with little to no enmity, violence or turmoil involved; very much improved from their fate IOTL, which is still pretty bad right now, especially since the Taliban's been operating in the region.

With Chitral itself also being a distinct possibility, perhaps even more likely than not. After all, IOTL, it was only under Aman ul-Mulk's predecessor as Mehtar of Chitral, Muhtarram Shah Kator III (1853-58), that it entered into treaty relations with the King of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammad Khan, and agreed to pay tribute to Afghanistan (in the form of providing an annual quota of Kafir slaves), before he could be overthrown for his tyranny; having previously been far more closely aligned with Kashmir. And ITTL, with Afghanistan likely to be far weaker in this region, and the Sikhs enduring as the chief power there, Chitral'd almost certainly be entering into treaty negotiations with, and becoming a tributary/vassal state of, the Sikh Empire instead, either earlier on or under Aman ul-Mulk's rule at the latest. But speaking for myself personally, that's as far as I was going to take the Sikhs' expansion into Afghanistan ITTL (along with Greater Badakhshan, as the NW-most extent of the Sikh Empire, maybe but not necessarily Laghman since it was also a breakaway province outside of Kabul's influence like Jalalabad, and possibly the region of Loya Paktia, since it used to be Kohat, not Khost, which was the 'capital' of this region/province before its partial conquest by the Sikhs cut off Kohat from the rest of the upper Kurram River valley IOTL, on the other side of the Peiwar Pass- even then though, only if the Sikhs/Sultan Mohammad Khan win their own equivalent/s of the Battle of Peiwar Kotal, which is far from a given).

From there though, looking farther afield, who can say how far the Sikhs'd go? IOTL, it's worth mentioning that one of the reasons the Sikhs were so jingoistic towards the Afghans, and to a lesser extent the Pashtuns of Baluchistan (i.e, the 'Derajat' region, which ultimately wound up being included as part of the Punjab by the British since the Sikhs had already conquered it) was the extent to which they were responsible for the slave trade across Central and Western Asia; with Barelvi's Jihadi movement, and the dissemination of the 'Sikha Shahi' narrative, having seen the Sikhs' border settlements deliberately targeted by Islamic fundamentalist slave raiders. Along with Barelvi, and those who supported his Jihadi campaign against the Sikhs, having been personally responsible for introducing the custom (which swiftly became endemic, and continued well into the early 20th century) of completely shaving the heads of all 'kafirs' taken in these slaving raids against the frontier territories' settlements, especially women, then chemically burning their scalps with quicklime so that their hair'd never regrow, rendering them easily recognizable, and preventing them from re-integrating with Sikh society.

And these easily identifiable slaves were predominantly sent via Afghanistan and Baluchistan, to Persian territory as well as to Arabia and the Central Asian Khanates' slave markets; with the British and other European observers estimating that these chemically de-haired slaves comprised over 10% of the slave chattel slaves being sold in the slave markets of Zanzibar, and over 20% of those in Afghanistan and Central Asia (such as Bukhara and Samarkhand) for decades, starting from this period and continuing long after the Sikh Empire fell IOTL. And the Omani dynasty was noted as being especially culpable in faciliting this, since they heavily employed the Baluchs as mercenary troops and later as traders, and generally controlled the naval routes via which this slave trade in Sikhs took place, via the possessions of the al-Bu Sa’id including the island of Bahrain, the Makran coast with its important strategic-commercial enclave of Gwadar, certain sites along the Persian coast such as Chabahar, the island of Socotra, the Curia Muria isles, Zanzibar, and nearby ports on the sub-Saharan African coast.

How long will the Sikhs let these atrocities against their people, their culture and their religion stand if/when they can do something about it? And why wouldn't they continue to go after the guilty parties, to attempt to stamp this out and protect their people, until the Central Asian and Indian Ocean slave trade's been ended once and for all?

Last edited:

Jackson Lennock

Well-known member

Would there be much conversion to Sikhism? Sikhs were at most 12% of the Sikh Empire historically. Even if the Balochis of Sindh convert, or perhaps the people of Nuristan as well, the Sikhs are still a significant minority group ruling over a predominately Muslim population (some 65 to 70 percent of the Empire's population historically).

I'm not confident the Sikhs would engage in overseas colonialism. Colonialism is costly, and they'd need to be ever-present of the threats to their north and west.

I doubt Britain moves the capital from Calcutta to New Delhi in a world where New Delhi is close to an international border.

I wonder how the prospect of at least two successful non-white countries emerging in the nineteenth century (Sikh Empire and Japan) impacts European racist attitudes.

I'm not confident the Sikhs would engage in overseas colonialism. Colonialism is costly, and they'd need to be ever-present of the threats to their north and west.

I doubt Britain moves the capital from Calcutta to New Delhi in a world where New Delhi is close to an international border.

I wonder how the prospect of at least two successful non-white countries emerging in the nineteenth century (Sikh Empire and Japan) impacts European racist attitudes.

Like I cited earlier in this thread, plenty of others historically converted, or were already deemed 'close enough' to self-identify as Sikhs even if the mainstream Sikhs at Amritsar would later exclude them as 'Nanakpanthis, not real Sikhs'. And the method via which so many so readily and swiftly converted to Sikhism was practically identical to that via which so many had converted to Islam in the first place. One of the primary reasons why Islam became more favorable in India was due to the establishment of Khanqah- commonly defined as a hospice, lodge, community center, or dormitory ran by Sufis. Khanqahs were also known as Jama'at Khana, large gathering halls. Structurally, a khanqah could be one large room or have additional dwelling space. Although some khanqah establishments were independent of royal funding or patronage, many received fiscal grants (waqf) and donations from benefactors for continuing services. Over time, the function of traditional Sufi khanqahs evolved as Sufism solidified in India.Would there be much conversion to Sikhism? Sikhs were at most 12% of the Sikh Empire historically. Even if the Balochis of Sindh convert, or perhaps the people of Nuristan as well, the Sikhs are still a significant minority group ruling over a predominately Muslim population (some 65 to 70 percent of the Empire's population historically).

I'm not confident the Sikhs would engage in overseas colonialism. Colonialism is costly, and they'd need to be ever-present of the threats to their north and west.

I doubt Britain moves the capital from Calcutta to New Delhi in a world where New Delhi is close to an international border.

I wonder how the prospect of at least two successful non-white countries emerging in the nineteenth century (Sikh Empire and Japan) impacts European racist attitudes.

Initially, the Sufi khanqah life emphasized a close and fruitful relationship between the master-teacher (sheikh) and their students. For example, students in khanqahs would pray, worship, study, and read works together. But the other major function of a khanqah was of a community shelter, with many of these facilities being built in low caste, rural, Hindu vicinities, and the Chishti Order Sufis especially establishing khanqahs with the highest form of modest hospitality and generosity. Keeping a "visitors welcome" policy, khanqahs in India offered spiritual guidance, psychological support, and counseling that was free and open to all people. The spiritually hungry and depressed caste members were both fed with a free kitchen service and provided basic education. By creating egalitarian communities within stratified caste systems, Sufis successfully spread their teachings, and it was this example of Sufi brotherhood and equity that drew people to the religion of Islam. Soon these khanqahs became social, cultural, and theological epicenters for people of all ethnic and religious backgrounds and genders. Through a khanqah's services, Sufis presented a form of Islam that forged a way for voluntary large scale conversions of lower class Hindus.

And perhaps the primary reason for Sikhism's rapid expansion in this period was that their Sikh Gurdwaras (and to a lesser extent, nominally 'Sikh' Mandirs and Havelis) took over from the Sufi Khanqahs, providing the same community shelter, free kitchen, basic education and counselling services that the Sufis had, to create egalitarian communities within the stratified caste systems. But to an even greater extent, and thus drawing people to Sikhism predominantly from the lower strata of the society as well, utilizing the same pre-established methodology which had converted them and their ancestors to Islam in the first place, aided greatly by the Sikh Empire allocating a markedly greater portion of its funds towards providing them with fiscal grants (which supported the continuation and expansion of these Gurdwaras' services) than those rulers who'd previously patronized the Sufi khanqahs had. Tthough Kharak Singh was noted for having personally provided equal patronage to the Sufi khanqahs and Bhakti mandirs as well, on the grounds of impartiality and true religious egalitarianism- mostly with disapproval, with this cited as one of the primary justifications for his contemporary characterization by the Sikh nobility in the Lahore Darbar as a 'naive, idealistic imbecile'.

With this trend having been exacerbated, and the pace of conversion from both Hinduism and Sufism to Sikhism increased, as mainstream Islam itself in the 19th century increasingly decried and persecuted Sufism as a heretical, with the rise of state-sponsored extremist Shi'ite clericalism having led to the widespread destruction of Sufi khanqahs and shrines on the part of hardline clerics across all the lands controlled by Shi'ite rulers (including the late Mughal, Durrani and Safavid Empires), leaving behind an increasing vacuum which was mostly filled by the establishment of Sikh Gurdwaras instead, across the lands controlled by the Sikhs. And examples of their efficacy in converting peoples to Sikhism can be seen by looking at the Bugtis of Dera Bugti (which may look relatively unimportant and barren at first glance, but which also happens to be where the overwhelming majority of natural gas reserves in the wider region are located, with its gas fields estimated to have larger reserves than the entirety of the UK and Mexico combined) and Khetrans of Barkhan as case studies.

Both were cited as being c.5-7% Sikh IOTL well into the 20th century; with this large Sikh minority almost exclusively attributable to the brief period in 1845-1847 when Sir Charles James Napier's force of over 7,000 men attacked the Bugtis, having declared the defiant Bugti tribe a 'criminal tribe' and placed a bounty of ten rupees on every man’s head, dead or alive. This was in spite of the British having had nothing but praise for their chivalry, asserting that they 'refused to surrender against heavy odds, preferred to fight hand to hand, never took advantage of the terrain, and never shot their enemies in the back', and their qualities as the 'most laborious and desirable peasantry among the turbulent and predatory Balouchs'. Instead, Napier's campaign was motivated seemingly almost entirely on the basis of spite and exasperation, having finally been forced to cede defeat in his efforts to attract them as recruits to the Company's armed forces on account of the Bugtis' point-blank refusal to give up their tribal attire (wearing traditionally all-white robes and turbans) or to contemplate cutting their hair or beards.

This forced thousands of Bugtis (along with hundreds of Khetrans, when the Marri then seized the opportunity to also attack both the greatly weakened Bugtis and the Khetrans, mounting heavy slaving raids against their settlements and seizing much of their lands for themselves), to flee across the border and take temporary refuge in the Derajat region of the Sikh Empire. And with these refugees having predominantly been granted refuge in the dormitories of Sikh Gurdwaras, almost the entirety of these refugees adopted Sikhism within that short 2-3 year period of time, with almost all of their descendants continuing to practice Sikhism from then onwards up until General Musharraf's progroms to islamicize Balochistan (in an attempt to stamp out support for the Baloch nationalist insurgency movement). Sikhism succeeded, and achieved its greatest period of growth during this period, primarily because it offered this social support network to its citizens, with the Sikh Empire implementing its basal version of the welfare state in this manner, and the Sikhs' Gurdwaras also serving the function of religiously institutionalized social welfare hubs (much like the Freedom Arches in Eric Flint's 1632 series, which can be summarized as 'Temples to spread the faith of American Exceptionalism across downtime Europe, just like Gurdwaras spread the faith of Sikhism, Bhakti Mandirs spread the faith of Bhakti Hinduism, and Khanqahs spread the faith of Sufism across India and Persia') to a markedly greater extent than they do today.

However, this trend was swiftly brought to a halt under British rule, as the British East India Company and its successor the British Raj effectively ended all state-sponsored revenue streams for these long-established traditional pre-existing theological welfare networks across British India, as well as enacting social engineering policies which saw the racial categorization of all groups and castes as "agricultural", "martial" (including the Sikhs), "criminal" and so on. The mid-19th century concept that behavior was hereditary rather than learned, which had been popularized by social reformers back in England such as Mary Carpenter (who'd coined the term "dangerous classes"), was applied across British India, thus racializing crime, with what was merely social determinism till then becoming entrenched as biological determinism, and with the Sikhs' new categorization as merely a "martial race of Hindus" thus all but ending any further conversions to Sikhism from other faiths. In an enduring Sikh Empire though, where these English philosophies of biological determinism would be extremely unlikely to be adopted, then this would've continued; and if people had continued to convert to Sikhism from other faiths at the same rate that they'd done on average over the course of Maharajah Ranjit Singh's rule, the percentage of its population who identified as Sikh would've been projected to surpass 25% by the 1870's, and become an absolute majority well before the outbreak of OTL's WW1.