Prior to being invaded and annexed by the British East India Company under the command of General Charles James Napier, the province of Sindh was ruled over by the Talpurs, whose dynasty had been established in 1783 by Mir Fateh Ali Khan Talpur, who declared himself the first Rais, or ruler of Sindh, after defeating the Kalhoras at the Battle of Halani. Prior to this, the Talpurs had served the previous Kalhora Dynasty (who'd been installed as the administrators and rulers of the Mughal imperial province, the 'Subah of Thatta' by Emperor Aurangzeb), dominating the Kalhora military, until 1775, when the Kalhora ruler had ordered the assassination of the chief of the Talpur clan, Mir Bahram Khan, leading to a revolt among the Talpurs against the Kalhora crown. Early Talpur rule was termed the 'First Chauyari', or "rule of four friends" - Mir Fateh, along with his brothers Mir Ghulam, Mir Karam, and Mir Murad. And ultimately, four separate branches of the Dynasty were established. The Talpur capital was declared to be Hyderabad, which had served as the capital of the overthrown Kalhoras. After his success, Fateh Ali Khan ruled the Shahdadani branch from Hyderabad, while his nephew established another branch of the dynasty, the Sohrabani, in Khairpur. Another relative, Mir Thara Khan, established the Mankani branch in southeast Sindh, around the area around Mirpur Khas - a city which was founded by his son Ali Murad Talpur. And a fourth branch, the Shahwani Talpurs of Tando Muhammad Khan, was also formed, though it became subordinate to the Shahdadani branch after the death of its founding ruler in 1813.

At their height, the Talpur brothers extended their rule over neighboring regions such as Balochistan, Kutch, and Sabzalkot (roughly corresponding with the present-day Rahim Yar Khan District of Pakistan), covering an area of over 100,000 square kilometers, with a population of approximately 4 million. They administered their realm by assigning jagirs to control individual land grants. During their rule, Syed Ahmad Barelvi (a Wahhabist Jihadi, who intended to establish a strong Islamic state on the north-west frontier in the Peshawar valley, as a strategic base for the future invasion of India, accompanied by an army of around 8,000 Mujahideen) tried to garner the Talpurs' support for his campaign against Maharajah Ranjit Singh, having sent an ultimatum to the ruler of the Sikh Empire demanding that he "either become a Muslim, pay Jizyah or fight and remember that in case of war, Yaghistan supports the Indians". With the rulers of Tonk, Gwalior and Rampur having been the primary supporters and funders of his newly declared Islamic Caliphate though, with the full consent of the British (who deemed it to be simply aiding an enemy of a nation they would soon be at war with), Barelvi was perceived to be a British agent, and these requests were turned down by the majority of the Talpurs- with the sole exception of 'Ali Murad, the younger half-brother of the then ruler of the Sohrabani branch Mir Rustam 'Ali Khan, who also supplied financial support to Syed Ahmad's 'Islamic Caliphate of Mardān', in the hopes of furthering his own ambitions, to weaken the Sikhs enough to make the conquest of the region of Multan (which had originally been part of the Kalhora Dynasty, and the Mughal Province of Thatta) possible.

In this short-term, original goal, 'Ali Murad failed- Syed Ahmad's efforts to reconcile between established power hierarchies, in pushing through aggressive and violent policies to enforce Sharia law (including efforts to collect the Islamic tithe of 10% of crop yields, the mandatory immediate marriage of all unwed girls above the age of 9, and flogging of any who who didn't pray) created strong opposition against him incited local revolts against him by the Pashtuns, forcing him and his Mujahideen to flee Peshawar for the hills, hoping to migrate and try his luck in Kashmir instead; Syed Ahmad was killed when an expeditionary force led by the first-born son of Maharajah Ranjit Singh's first wife, future Maharajah Sher Singh (having been entrusted with the task upon his recent appointment as Governor of Kashmir, a post which he'd hold until 1834) stormed his Mujahideen's final refuge at Balakot Maidan in the mountainous valley of Mansehra district on the 6th May 1831, and the early Indian Wahhabi movement fell with him. And the devastation of the Sohrabani Talpurs' diplomatic relations with the neighbouring Sikh Empire caused by their support of Syed Ahmad Barelvi's campaign, along with the Sikh Empire's rumored preparations for a retaliatory invasion to conquer the region of Chandūka (corresponding with the present-day Larkana Division) from them in restitution, were massive factors in 'Ali Murad's decision to follow the same strategy to escape the wrath of the Sikhs that the rulers of Tonk, Gwalior and Rampur had- signing a treaty with the British in 1832, in which he secured recognition as the independent ruler of Khairpur in exchange for surrendering control of foreign relations to the British in 1838, as well as use of Sindh's roads and the Indus River. But this did enable 'Ali Murad to oust his elder brother, and secure his ascension to become ruler of the Sohrabani Talpurs unopposed.

And the divisions among the Talpurs, such as 'Ali Murad's subsequent request to the British to seize Karachi from the Shahdadani Talpur dynasty in Hyderabad on his behalf in 1839, would allow the British to eventually conquer Sindh in relatively short order IOTL. Even prior to the signing of 'Ali Murad's treat with the British, after ascending to become the ruler of the Mankani Talpur dynasty in Mirpur Khas in 1829, Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur, who later became known by the moniker "Lion of Sindh" had established friendly relations with the Sikh emperor Maharajah Ranjit Singh, seeking to form an alliance against the British. This alliance, though, was stymied partially by an invasion of Upper Sindh conducted by the deposed Shah Shuja Durrani in 1832 (again, with the financial support of the British), which the Talpurs united against to defeat, and ultimately failed to endure beyond Maharajah Ranjit Singh's death IOTL. Instead Sindh was annexed to British India under the East India Company following the conquest of Sindh by Charles James Napier and defeat of Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur on 24 March 1843 at the Battle of Dubbo (during which, some local Sindhi jagirs are reported to have taken bribes from British forces, and aimed their guns towards Talpur Baloch forces). After this defeat, Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur and his remaining men retreated into the rural areas, where they continued a enduring counter-insurgency (inspiring Napier's invention of the term 'counter-insurgency) against the British invaders, with the 'Lion of Sindh' surviving until the 24th August 1874.

Following the British victory, and consequent annexation of the Sindh, troubles quickly arose. The authorities in England were not pleased with the annexation of the Sindh, which wasn't nearly as prosperous as Napier had claimed it would be after capture, and popular sentiment at the time was that the territory should be restored to the Talpur Amirs. However, the British East India Company ultimately decided that, since the process of returning the Sindh to its original owners would be difficult, and the forced resignation of Ellenborough and Napier would cause further criticism from England (with the government back in England having already written to Napier and Ellenborough, condemning the annexation and their actions), the ownership of the Sindh would remain with the British, who divided it into districts and integrated it as part of the Bombay Presidency. 'Ali Murad, who had helped the British in 1845-7 during the Turki campaign, was then accused by the British of plotting against them in 1851–2, and so was stripped of his lands in upper Sindh by the British East India Company.

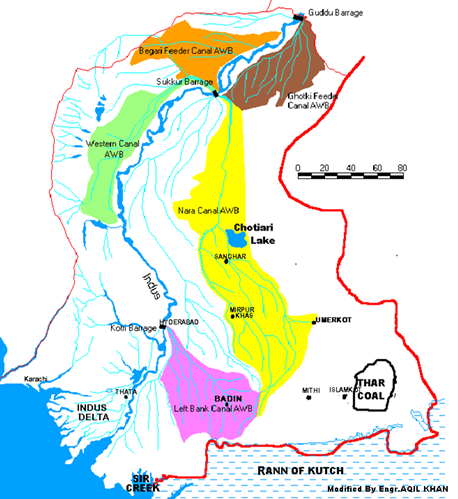

So then, that's most of the relevant backstory in the region, and how things played out IOTL. But what if the Sindh region had fallen into the hands of the Sikhs instead? Let's say that the Sikh Empire's rumored campaign to enact retribution against, and extort restitution from, Khairpur and the Sohrabani Talpurs for their support of Syed Ahmad's Islamic Caliphate, commences before 'Ali Murad manages to secure a treaty with the British for their protection ITTL; seizing Chandūka (Larkana Division, corresponding with the Sohrabani's territorial extent west of the Indus, and thus free for the taking under the Treaty of Amritsar) at the very least. And/or that the alliance between The Sikh Empire and the Mankani Talpurs then subsequently endures and strengthens rather than weakening and being largely abandoned after Maharajah Ranjit Singh's death, with Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur requesting that the Sikhs seize Karachi from the Shahdadani Talpurs on his behalf instead ITTL in the manner that Mir Ali Murid Talpur requested it of the British IOTL, and the entirety of Sindh (west of the Indus river at least) subsequently falling into the hands of the Sikh Empire. How long could they hold onto it- perhaps even indefinitely? And how much stronger would the Sikh Empire's position be ITTL, with the entirety of Sindh either brought into their possession or brought under their influence via their alliance with the Mankani Talpurs and the 'Lion of Sindh', standing together in unwavering opposition to the British until at least the mid 1870's?

At their height, the Talpur brothers extended their rule over neighboring regions such as Balochistan, Kutch, and Sabzalkot (roughly corresponding with the present-day Rahim Yar Khan District of Pakistan), covering an area of over 100,000 square kilometers, with a population of approximately 4 million. They administered their realm by assigning jagirs to control individual land grants. During their rule, Syed Ahmad Barelvi (a Wahhabist Jihadi, who intended to establish a strong Islamic state on the north-west frontier in the Peshawar valley, as a strategic base for the future invasion of India, accompanied by an army of around 8,000 Mujahideen) tried to garner the Talpurs' support for his campaign against Maharajah Ranjit Singh, having sent an ultimatum to the ruler of the Sikh Empire demanding that he "either become a Muslim, pay Jizyah or fight and remember that in case of war, Yaghistan supports the Indians". With the rulers of Tonk, Gwalior and Rampur having been the primary supporters and funders of his newly declared Islamic Caliphate though, with the full consent of the British (who deemed it to be simply aiding an enemy of a nation they would soon be at war with), Barelvi was perceived to be a British agent, and these requests were turned down by the majority of the Talpurs- with the sole exception of 'Ali Murad, the younger half-brother of the then ruler of the Sohrabani branch Mir Rustam 'Ali Khan, who also supplied financial support to Syed Ahmad's 'Islamic Caliphate of Mardān', in the hopes of furthering his own ambitions, to weaken the Sikhs enough to make the conquest of the region of Multan (which had originally been part of the Kalhora Dynasty, and the Mughal Province of Thatta) possible.

In this short-term, original goal, 'Ali Murad failed- Syed Ahmad's efforts to reconcile between established power hierarchies, in pushing through aggressive and violent policies to enforce Sharia law (including efforts to collect the Islamic tithe of 10% of crop yields, the mandatory immediate marriage of all unwed girls above the age of 9, and flogging of any who who didn't pray) created strong opposition against him incited local revolts against him by the Pashtuns, forcing him and his Mujahideen to flee Peshawar for the hills, hoping to migrate and try his luck in Kashmir instead; Syed Ahmad was killed when an expeditionary force led by the first-born son of Maharajah Ranjit Singh's first wife, future Maharajah Sher Singh (having been entrusted with the task upon his recent appointment as Governor of Kashmir, a post which he'd hold until 1834) stormed his Mujahideen's final refuge at Balakot Maidan in the mountainous valley of Mansehra district on the 6th May 1831, and the early Indian Wahhabi movement fell with him. And the devastation of the Sohrabani Talpurs' diplomatic relations with the neighbouring Sikh Empire caused by their support of Syed Ahmad Barelvi's campaign, along with the Sikh Empire's rumored preparations for a retaliatory invasion to conquer the region of Chandūka (corresponding with the present-day Larkana Division) from them in restitution, were massive factors in 'Ali Murad's decision to follow the same strategy to escape the wrath of the Sikhs that the rulers of Tonk, Gwalior and Rampur had- signing a treaty with the British in 1832, in which he secured recognition as the independent ruler of Khairpur in exchange for surrendering control of foreign relations to the British in 1838, as well as use of Sindh's roads and the Indus River. But this did enable 'Ali Murad to oust his elder brother, and secure his ascension to become ruler of the Sohrabani Talpurs unopposed.

And the divisions among the Talpurs, such as 'Ali Murad's subsequent request to the British to seize Karachi from the Shahdadani Talpur dynasty in Hyderabad on his behalf in 1839, would allow the British to eventually conquer Sindh in relatively short order IOTL. Even prior to the signing of 'Ali Murad's treat with the British, after ascending to become the ruler of the Mankani Talpur dynasty in Mirpur Khas in 1829, Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur, who later became known by the moniker "Lion of Sindh" had established friendly relations with the Sikh emperor Maharajah Ranjit Singh, seeking to form an alliance against the British. This alliance, though, was stymied partially by an invasion of Upper Sindh conducted by the deposed Shah Shuja Durrani in 1832 (again, with the financial support of the British), which the Talpurs united against to defeat, and ultimately failed to endure beyond Maharajah Ranjit Singh's death IOTL. Instead Sindh was annexed to British India under the East India Company following the conquest of Sindh by Charles James Napier and defeat of Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur on 24 March 1843 at the Battle of Dubbo (during which, some local Sindhi jagirs are reported to have taken bribes from British forces, and aimed their guns towards Talpur Baloch forces). After this defeat, Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur and his remaining men retreated into the rural areas, where they continued a enduring counter-insurgency (inspiring Napier's invention of the term 'counter-insurgency) against the British invaders, with the 'Lion of Sindh' surviving until the 24th August 1874.

Following the British victory, and consequent annexation of the Sindh, troubles quickly arose. The authorities in England were not pleased with the annexation of the Sindh, which wasn't nearly as prosperous as Napier had claimed it would be after capture, and popular sentiment at the time was that the territory should be restored to the Talpur Amirs. However, the British East India Company ultimately decided that, since the process of returning the Sindh to its original owners would be difficult, and the forced resignation of Ellenborough and Napier would cause further criticism from England (with the government back in England having already written to Napier and Ellenborough, condemning the annexation and their actions), the ownership of the Sindh would remain with the British, who divided it into districts and integrated it as part of the Bombay Presidency. 'Ali Murad, who had helped the British in 1845-7 during the Turki campaign, was then accused by the British of plotting against them in 1851–2, and so was stripped of his lands in upper Sindh by the British East India Company.

So then, that's most of the relevant backstory in the region, and how things played out IOTL. But what if the Sindh region had fallen into the hands of the Sikhs instead? Let's say that the Sikh Empire's rumored campaign to enact retribution against, and extort restitution from, Khairpur and the Sohrabani Talpurs for their support of Syed Ahmad's Islamic Caliphate, commences before 'Ali Murad manages to secure a treaty with the British for their protection ITTL; seizing Chandūka (Larkana Division, corresponding with the Sohrabani's territorial extent west of the Indus, and thus free for the taking under the Treaty of Amritsar) at the very least. And/or that the alliance between The Sikh Empire and the Mankani Talpurs then subsequently endures and strengthens rather than weakening and being largely abandoned after Maharajah Ranjit Singh's death, with Mir Sher Muhammad Talpur requesting that the Sikhs seize Karachi from the Shahdadani Talpurs on his behalf instead ITTL in the manner that Mir Ali Murid Talpur requested it of the British IOTL, and the entirety of Sindh (west of the Indus river at least) subsequently falling into the hands of the Sikh Empire. How long could they hold onto it- perhaps even indefinitely? And how much stronger would the Sikh Empire's position be ITTL, with the entirety of Sindh either brought into their possession or brought under their influence via their alliance with the Mankani Talpurs and the 'Lion of Sindh', standing together in unwavering opposition to the British until at least the mid 1870's?

Last edited: