Culturally, the 1950s and early 60s were of course a very interesting time in Cambridgeshire, with the revelation of the spy ring and the start of the rise of Footlights and its huge impact on British comedy. Sadly that didn’t really translate to the area’s politics, which were pretty dull for much of the early part of the period and look that way for almost all of it on the map; the boundaries of the four constituencies remained untouched in the 1955 boundary review and other than a slight but steady swing to the Tories, they didn’t prove that interesting.

The first interesting occurrence was the 1962 Cambridgeshire by-election, where Francis Pym was first elected. Pym was a Cabinet minister under Heath and Thatcher, and under the latter became prominent as a major ‘wet’ critical of Thatcher and Foreign Secretary during the Falklands War. Probably his most famous moment was saying during the 1983 election campaign that ‘Landslides, on the whole, don’t produce successful governments’, for which Thatcher sent him to the backbenches.

As with most places, 1966 saw a big swing to Labour, enough for them to almost take the Isle of Ely and, more noticeably, to successfully take Cambridge. Perhaps not surprisingly given the city’s emerging countercultural left, the Labour MP elected there, Robert Davies, was a CND supporter and vocal critic of Harold Wilson’s policy on Vietnam. However, he died only 15 months after being elected and given Labour’s odds of holding

safe seats in the 1966-70 term was touch-and-go, it should be no surprise to find out the Tories easily recaptured it.

After an even duller election in 1970 where not only did the Tories win every seat easily but with the National Liberals being wound up the map turns all blue, 1973 saw a by-election in the Isle of Ely held at the peak of the early 70s Liberal revival. Thanks to this and the unpopularity of the Heath government, the Liberals retook the seat for the first time in 38 years with celebrity candidate Clement Freud, at the time known as Sigmund’s grandson and a prominent broadcaster and later for being Richard Curtis’s father-in-law, but now of course known for the other, far more horrifying thing he has in common with Cyril Smith besides being a long-serving Liberal elected at a 70s by-election.

Moving swiftly on… something notable about the 1974 boundary changes is the absurd situation that explains them. See, as far back as 1947 the Local Government Commission had observed that the four counties comprising Cambridgeshire were too small to continue existing separately while providing local services, particularly because both Cambridge and Peterborough wanted to become county boroughs. When it was suggested they should all be amalgamated into one county, this was heavily opposed, and so when they pointed this out again in 1960 and got slapped down again, two new counties of ‘Huntingdonshire and Peterborough’ and ‘Cambridgeshire and Isle of Ely’ were created. These counties, two of the only ones reformed before 1972, were so stupidly unwieldy they led everyone to give up and agree to a single county of Cambridgeshire at last.

As this implies, 1974 saw

Peterborough reintegrated into the county (incorporating Thorney from the Isle of Ely), as well as Cambridge being expanded to comprise the redrawn boundaries of the city; the boundaries were actually still coterminous with their respective counties and boroughs’ boundaries. Peterborough’s extreme political volatility in this period really stands out- in 1966 it had been decided by 3 votes, and in February 1974 it was decided by only 22. It was then one of the seats Labour gained in October to get to a threadbare parliamentary majority.

There were a handful of colourful candidacies in the mid-1970s worth mentioning: in both 1974 elections the Liberals ran the founder of Pizza Express as their candidate in Peterborough, and in the 1976 Cambridge by-election the main event of note was the candidacy of Philip Sargent, who used the label ‘Science Fiction Looney’, inspiring the naming of the Official Monster Raving Looney Party founded six years later. (I actually find the ‘science fiction’ part of the label more interesting though, since it predates both the rise of Douglas Adams and most of Cambridgeshire’s tech industry boom.) He used the candidacy as an opportunity to put out literature attacking the National Front candidate (who got fewer than double the votes he did) and, despite intending to set a Guinness world record for fewest votes, ended up getting loads of votes from students. 1979 saw two more notable Tories get elected. Huntingdonshire, of course, voted in John Major, the most powerful boring man who ever lived, while the Tory who retook Peterborough was Brian Mawhinney, later Major’s party chairman.

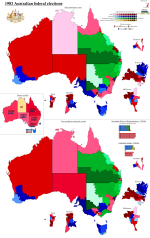

By 1983, the boundaries were completely overhauled, with all the existing rural constituencies being abolished. Huntingdonshire was renamed Huntingdon since it was no longer contiguous with the county and took in a big chunk of Peterborough, Isle of Ely had Ely removed from it and was renamed

North East Cambridgeshire, and historic Cambridgeshire and Ely were used to create

South East Cambridgeshire and

South West Cambridgeshire, with South West also taking two wards from Cambridge.

Predictably, every seat except North East went strongly for the Tories, with North East flipping to them in 1987 and Cambridge staying blue despite the SDP literally running Shirley Williams there in her last run for Parliament. While you probably wouldn’t have guessed at the time, this would actually be the last time the Tories won every seat in Cambridgeshire, as in 1992 Labour’s candidate Anne Campbell narrowly gained Cambridge. (Funnily enough, apparently she was one of my dad’s maths teachers and badly underestimated his predicted grades!) Also of note is that for some reason, Huntingdon

loved Major- in all three elections in this period he took over 60% of the vote and in 1992 he set a record for the largest numerical majority of any British MP, 36,230 votes, that would stand for the next 25 years.

Further population growth in the area, aided by the rise of the ‘Silicon Fen’ tech industry centred around Cambridge, meant Cambridge gained another seat in 1997, and the seats were redrawn significantly once again. A new

North West Cambridgeshire seat was drawn up from northern Huntingdonshire and western Peterborough, South East Cambs shifted northeast to make North East Cambs smaller, and South West Cambs was renamed

South Cambridgeshire despite covering the south western part of the county (I’ve never understood that change, honestly).

Even in an area as Tory as this, the Labour landslide of 1997 can sort of be seen- even in the safe seats the margins got massively slashed, especially in North East Cambs where Labour had taken control of Fenland District Council two years prior, and they gained Peterborough resoundingly as well as massively bolstering their margin in Cambridge. (North West Cambs gave Mawhinney somewhere to flee to, though.) Amusingly, the Major effect is still very visible even there- look at how the margin drops after he retires in 2001!

1997 saw two notable MPs elected to Cambridgeshire for the first time- Andrew Lansley in South Cambs, a former Conservative Central Office researcher who later became a very, very hated Health Secretary under Cameron, and Helen Brinton (later Clark) in Peterborough, who started out as a Blairite but her personal popularity declined fairly quickly; she then rebelled against the party line on Iraq and quit the Labour Party after she lost her seat in 2005. Speaking of 2005, that election also saw the Lib Dems gain Cambridge off Labour thanks to Campbell’s failure to oppose tuition fees.

The constituencies were kept the same with some minor boundary changes in 2010, so by now are quite significantly over quota and from what I gather are being substantially redrawn for the next election. A sort of north-south divide can be seen in the 2010 results as the Lib Dems improved their results in the two rural southern seats and held Cambridge easily, while the Tories resoundingly held the northern seats. Speaking of the northern seats, current Cabinet minister Steve Barclay was elected in North East for the first time at this election.

Funnily enough, I actually got to meet a bunch of the candidates in 2015 through them coming to my sixth form. I can’t say I have anything nice to say about Lucy Frazer (South East Cambs), who carpetbagged up here after failing to get selected in Harrow and frankly always come across as a suck-up backbencher. On the other hand, I vividly remember Heidi Allen (South Cambs until 2019) giving a talk to my class and remarking that she ‘couldn’t wait to rebel’- considering she jumped ship to Change UK, The Independents and the Lib Dems in her last year in the Commons, she was more truthful about that than I assumed at the time.

Of course, the actually interesting fight was in Cambridge itself, the only really competitive constituency in the area. The Lib Dem incumbent, Julian Huppert, was actually quite personally popular despite everything, while I remember a lot of people didn’t think much of Daniel Zeichner by comparison, but trying to get elected as a Lib Dem in 2015 was just too much of a millstone, and Zeichner proved likeable enough in Parliament that the Lib Dems haven’t been able to threaten him since.

2017 saw Labour retake Peterborough, and they held it against the briefly ascendant Brexit Party in the 2019 by-election before losing it that December. The really interesting thing in 2019, though, was South Cambs- the council went strongly for the Lib Dems in the local election that year and it swung heavily against the grain due to being similarly strongly pro-Remain to Cambridge itself. Its swing away from the Tories has continued to the point that when the mayoral elections came in 2021, it helped Labour win the mayoralty off of Tory incumbent James Palmer (or ‘that idiot in Soham’ as one of my dad’s friends nicknamed him).

While I don’t want to count my chickens, I feel like the politics of Cambridgeshire is heading in an interesting trajectory. As mentioned, South Cambs is a very attractive future battleground for the opposition, I’ll be interested to see if Cambridge swings away from Labour as and when they get back into government, and Peterborough seems to be stabilising as a core bellwether again (I forget which forum, but someone suggested it’s developing a similar demography to Bedford- a lot of young, working-class and non-white voters in the area than there used to be- and this is making it friendlier ground for Labour than it’s historically been).

I feel like this might not have been that interesting in the grand scheme of things, but hey, I had fun with it! (By the way, thanks again for the map Alex- I found it particularly interesting to see the city core of Peterborough in 1974 perfectly aligns with the 1997-2010 constituency.)