An update on the list of PMs for the Dual Monarchy idea (still a WIP). I think it's gotten a bit out of hand.

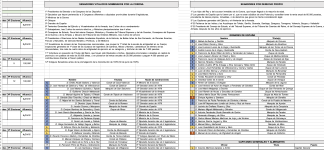

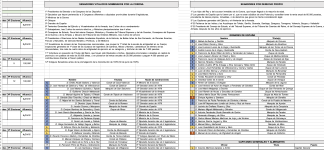

Two-And-Two-Halves Party Era (1868-1902)

1868-1872:

Victor Antoine d'Aubigny (Liberal)

1868: Liberal (), Moderate (), Trialist (82), Anti-Revolutionary (), Independents (21)

1870: Liberal (), Moderate (), Trialist (91), Anti-Revolutionary (), Independents ()

In his first stint as cabinet chairman, D'Aubigny continued the policies of his Liberal predecessors, marked by a preference for industrialists and urban bourgeois over agrarian interests and a general rejection to expand the franchise, except for the recognition of additional chambers of commerce with representation rights. Electorally speaking, the main change under the first four years of the D'Aubigny government was the 1869 law to bar priests from voting or standing for office.

Although historiography has focused on D'Aubigny’s anti-clericalism and his conflict with the progressives within his party, the most outstanding achievements, as perceived by his contemporaries, of his first few years in power was a rash of laws and ordinances that extended the ‘extension’, the common area of untaxed trade of goods, to the entire Kingdom, removing the right of provinces to tax trade across provincial lines as well as across the Irish Sea and the English Channel, as well as those taxes imposed on southern French goods crossing provincial lines since the 14th century. Likewise, the government removed all export taxes.

In early 1871, the Liberal government moved to remove the right of cities to collect the

octroi, a consumption tax on goods sold within city walls. The removal of the

octroi, whose collection was oftentimes a privilege granted by royal charter to certain cities, proved the most challenging obstacle of the Liberal attempts to unify the Double Monarchy into a unified trade and customs zone, as in many cases, the tax represented the leading share of a city’s income.

Although the bill became law, it faced a great deal of opposition from the cities by removing one of their main source of revenue and traditional privileges. In particular, the consuls of Marseille, who resented the loss of free port status for the city, led a major petition to the Assembled Estates in opposition to the bill. The public procession and demonstration ended in a three-day-long fight between the city’s militia and protesters, which had to be put down by troops sent from Toulon.

The need for new revenues to finance the municipalities, and the expenses related to the economic downturn of 1871, including public works (like the demolition of cities’ former fiscal walls), required the Liberal government to raise taxes and, in particular, to explore the option of a tax on direct inheritances, which created a wave of backlash from the Liberals’ traditional support base amongst wealthy urban patricians.

1872-1874:

Hugh M. Charles Percy (Moderate)

1872: Liberal (), Moderate (), Trialist (), Anti-Revolutionary (), Independents ()

The dire economic climate and the general dissatisfaction of traditional Liberal voters with the government led to numerous losses in 1872, where the Liberals came on top but failed to obtain a majority, as many of their voters in competitive seats could not show up to vote. Instead, the Moderates managed to put together a very tenuous minority government.

The Percy government was supported by a parliamentary group that remained smaller still than the Liberals, and backed externally by an odd mix of conservative Trialists and more moderate Anti-Revolutionaries, was - and has remained - an example of a weak government.

The main accomplishment of the short-lived Percy government was passing a new electoral law enshrining secret voting by introducing voting booths, pre-printed ballot papers, and the option to vote for a party’s candidate slate at large instead of one of the individual candidates listed.

Other than that, the repeated efforts to pass protectionist legislation to raise the beleaguered state finances and protect farmers met fierce resistance from industrialists and urban middle classes, who would flock back, in large numbers, to the Liberal camp.

1874-1884:

Victor Antoine d'Aubigny (Liberal)

1874: Liberal (), Moderate (), Trialist (101), Anti-Revolutionary (), Independents ()

1876: Liberal (), Moderate (), Trialist (), Anti-Revolutionary (), Independents ()

1878: Liberal (), Moderate (), Trialist (), Anti-Revolutionary (), Independents ()

1880: Liberal (), Moderate (), Trialist (), Anti-Revolutionary (), Independents ()

1882: Liberal (); Moderate (), Trialist (), Anti-Revolutionary (), Independents ()

D'Aubigny will be forever remembered for his paradoxes. History remembers him as the “authoritarian liberal” and the “conciliatory extremist”. The 10-year premiership represented the peak of Liberal political dominance in the post-revolutionary period and the start of its collapse as a governing power.

Following the brief interregnum under Percy, the Liberals set out to consolidate power, having learnt the lesson from the 1868-72 period. In the process, D'Aubigny broke his party - to the extent that a 19th-century party was a party.

Franchise was expanded as far as convenient to enfranchise urban middle classes. At the same time, local liberal associations (‘circles’) were fostered, and their role in selecting candidates (through the so-called ‘pools’) was often used as proof of the Liberals’ commitment to liberalism, compared to the lack of structure of the Moderate camp.

Moreover, in 1874, the government passed new legislation reforming the rules on the judiciary to set age caps for judicial officers in courts subject to direct royal jurisdiction. As numerous judges were over or nearing the capped age of sixty-five, particularly those inherited from the pre-revolutionary era, the government expected to be able to replace them with ideologically aligned ones, which it proceeded to do throughout the following decade.

More radically, the Liberal government, as part of its electoral “reinforcement” and anticlerical agendas, attempted to establish a special commission to “advice” the Monarch in the appointment of bishops and archbishops, essentially supplanting the monarch’s role as a way to control the appointment of more liberal or Liberal-friendly figures from the religious hierarchy.

The response to the plan was nothing short of dramatic - sessions in the Estates became fierce, with occasional fistfights breaking up between liberal and moderate members, petitions from the provinces flooded the capital, and the Holy See withdrew its

Nunzio. The political effervescence prompted the Queen Regent to intervene and request D'Aubigny to withdraw the bill, to which - as legend has it - he acquiesced in the least polite manner, making an enemy of the Court.

All the same, the government would respond by removing their legation from Rome. At the same time,

sudiste Liberal members of the Estates delivered aggressive speeches calling for the annexation of the Comtat Venaissin that resulted in heckling from opposition members.

Tensions were high, and the Interior Ministry had to declare a state of emergency and issue

lettres d’ordinance [3] suspending charter-enshrined rights in parts of Brittany, Normandy and Kent, where groups led by radical clergymen attacked symbols of civil power, and troops had to be deployed to quench the clerical revolt.

The violence of the reaction prompted a ministerial push for moderation in the Cabinet, where various ministers led by Martin Bisson, the Interior Minister and Georges Perronet Thompson, the Grace and Justice Minister (despite his own anti-clericalism), forced D’Aubigny to relent on the anticlerical policies to put an end to the civil unrest, at least until 1883 with the presentation of the school bill.

In line with the party’s preferred approach, the d’Aubigny government continued to push for free trade, and the sponsoring of economic initiatives, such as the support for the creation of credit institutions and in particular of the Royal Savings Bank and the Land Credit (where their credit was guaranteed by the state) to support credit and savings among the lower classes of society.

Likewise, efforts were made for the drainage of wetlands to increase agricultural production. In Ireland, Brittany, Normandy and Maine, the land question remained unanswered, however, as the d’Aubigny government continued to ignore pleas for land reform and redistribution.

Agrarian reform, while not a pressing issue in either Kingdom, would, as the 1880s rolled in, and paired with the looking economic situation, give birth to the Irish agrarian reform movement.

The year 1880 saw the peak of tensions between the Dual Monarchy and its Burgundian rivals over the control of the Malabar coast. Already in direct control of the island of Eelam and indirectly over the Carnatic region through the Madurai protectorate, an opportunity for the expansion of the Dual Monarchy’s influence in the southern Indian region appeared when

Nayak Rajasimha V died, resulting in a succession conflict between Prince Rajadhi Rajasingha (supported by the Dual Monarchy) and the brother of the late monarch, Narenappa Nayakkar, who was considered either a proxy or a friend of Burgundian interests.

Both European powers, constantly at odds in their foreign entanglements, supported militarily and economically each of their junior partners in an effort to establish commercial and military supremacy in and around Eelam as a way to control access to Insular India and, ultimately, Annam and China.

In this dressed-up conflict [4], which outlasted the d’Aubigny government’s tenure, tensions between the two neighbouring European powers, rose resulting in a trade war between the Dual Monarchy and Burgundy, with each country introducing punitive tariffs and increasing movement across the long borders between two European hegemons.

Fears of a land war prompted d’Aubigny’s government to increase the intake of conscripted men from across the Monarchy’s lands and to shift spending to military matters to increase preparedness. Both decisions, while logical given the circumstances, caused popular discontent in the countryside - where the conscription of an adult son took away free labour - and among the ranks of the Trialists and the progressive Liberals.

In the parliamentary debates that took place throughout late 1880 and into 1881, the conflict between d’Aubigny’s orthodox liberals and the progressive ones worsened, and it brought into the limelight young up-and-coming progressive politicians, well-known for their rhetoric skills, like Pascal Harrington and Jules Barrès, who rallied against the increased mobilisation of men, and linked the struggle against working-class and rural mobilisation with that for the expansion of the suffrage.

The direct economic costs of the conflict were limited, however, the resulting trade conflict with neighbouring Burgundy and the economic depression - particularly in rural areas which could not compete with Russian or North American grain imports - mounted, and resulted in a general economic downturn that characterised the middle part of the 1880s. Overall economic conditions worsened, and the country re-entered into recession in 1881.

With a flailing economy, foreign troubles and a divided party, the D’Aubigny cabinet embarked on the tried-and-tested anticlerical - some might say anti-Catholic - policy. The way to do it was, again, on education.

The non-controversial aspect of the policy was the establishment of royal education foundations to fund secular scholarships and chartering of additional secular universities ...

The question of suffrage expansion would become a recurrent one over the long Liberal government. The expansion of the franchise in urban areas back in 1875 had already put the question back on the agenda, but d’Aubigny had successfully used his dominance over the parliamentary party

Come early 1884, and following the awful result liberal candidates had obtained in

1884-1887:

Gathorne Hardy (Moderate)

1884: Moderate (), Liberal (), Trialist (), Anti-Revolutionary (), Independents ()

1886: Moderate (), Liberal (), Trialist (), Anti-Revolutionary (), Irish Agrarian (), Independents (), Workers’ ()

AA

The combative approach of the premier can perhaps be best exemplified by the quixotic fight he picked against the provost and

échevins of Paris over the civil funerals (“

la guerre des funérailles” as the French press would come to call it mockingly). Paris, ever the ultra-liberal bastion, covered the expenses for civil funerals (often used by Jews, Protestants and franc-masons) but not for Catholic funerals (which had to be borne out of pocket).

This approach, which was deemed every bit as unnecessarily over-the-top and authoritarian as the previous ten years of Liberal government would greatly hurt Hardy in the internal fight between the party factions.

1887-1889:

H. H. Molyneux-Herbert (Moderate)

1888: Moderate (), Liberal (), Trialist (),

AA

Ultimately, Molyneux-Herbert was not to be remembered as a great cabinet chairman, but he should be remembered as the great builder of the party apparatus.

1889-1893:

Camille de Meaux (Moderate)

1890: Moderate (), Liberal (),

1892: Moderate (), Liberal (),

AA

The bon-vivant premier would be undone by his

1893-1901:

Guilhèm Peytes de Montcabrier (Moderate)

1894: Moderate (),

1896: Moderate (),

1898: Moderate (),

1900: Moderate (),

AA

1901:

Stanislas de Broqueville (Moderate)

AA

1902-1905:

William Georges d’Harcourt (Moderate)

1902: Moderate (),

1904: Moderate (),

AA

Also, thanks to the magic of AI:

Instrument of Government, 1851

An Act to establish an Instrument for the establishment of a free and representative Government of the Dual Monarchy of England and France, and to provide for the Rights and Liberties of the Peoples, Orders and Nations thereof.

Whereas His Most Christian Majesty King Henry IX, by the Grace of God, King of England, France and Jerusalem; Duke of Brittany, of Provence, &etc.; Count of Provence, &etc.; Lord of Ireland, &etc., Defender of the Faith, and his heirs and successors, being lineally descended from His Most Christian Majesty King Henry V, who by his valour and wisdom united the crowns of England and France in the year of our Lord one thousand four hundred and twenty-two, have been pleased to delegate their power and authority over their loyal subjects, and to consent to the establishment of a free and representative government in their dominions, under certain conditions and limitations:

And whereas a great and glorious Revolution has taken place in the said dominions, whereby the people have asserted their natural and imprescriptible rights to liberty, equality, and fraternity, and have demanded a reform of the ancient and oppressive laws and institutions that have long afflicted them:

And whereas it is expedient and necessary to frame and establish a new Instrument of Government for the said Union of the Kingdoms of England and France, whereby the rights and liberties of the people may be secured, the prerogatives and dignity of the Crown may be preserved, the peace and harmony of the nations may be maintained, and the welfare and prosperity of all may be promoted:

And whereas it is expedient to settle the new Instrument of Government of the said Dual Monarchy upon such principles as may ensure the peace, prosperity and happiness of the same, and to define the powers and functions of the several institutions thereof:

Be it therefore enacted by His Most Christian Majesty King Henry X, by and with the advice and consent of His Royal Highness Prince Edward Albert, Regent of the said Dual Monarchy, as follows:—

PART I.—PRELIMINARY.

General.

1. Short title.— This Act may be cited as the Instrument of Government, 1851.

2. Commencement.— This Act shall come into force on the first day of January in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and fifty-two.

[...]

PART II.—THE CROWN.

16. Majesty.— (1) His Most Christian Majesty shall be the Head of State over all persons and things within his dominions.

(2) His Most Christian Majesty shall exercise his executive power through His Secretaries of State who shall be responsible to the Assembled Estates for all acts done in his name.

Regency.

17. Regency.— (1) His Most Christian Majesty King Henry X shall continue to be by right King of England, of France and of Jerusalem, &etc., Defender of the Faith.

(2) Notwithstanding the provisions of subsection (1) of this Section, He shall exercise no power or authority in or over any part of the Dual Monarchy or its dependencies until he shall attain his full age of eighteen years.

(3) During his minority all such power and authority shall be vested in His Royal Highness Prince Edward Albert Victor, Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, as Regent.

18. Coronation and oath.— His Most Christian Majesty King Henry X shall be crowned with all due solemnity following the traditions and rites of the Kingdoms of England and France as soon as conveniently may be after he shall attain his full age; but that before he shall be so crowned he shall take and subscribe an oath to maintain and preserve inviolably the settlement herein contained.

19. Marriage.— His Most Christian Majesty King Henry X, and his descendants shall marry with such person as shall be approved by the Assembled Estates; but that no person who is not a member of the Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church shall be capable of being Queen Consort.

[...]

PART III.—THE ASSEMBLED ESTATES.

General.

??. Constitution.— (1) The delegates of three orders of His Most Christian Majesty’s Realms and of His Lands and Nations shall form the Assembles Estates of the Realm.

(2) The legislative power of the Dual Monarchy shall be vested in His Most Christian Majesty and in the Assembled Estates jointly.

(3) The Assembled Estates shall consist of seven hundred and fifty members.

Constitution.

??. Orders.— (1) The members of the Assembled Estates shall be divided into three orders: ecclesiastical, noble, and common.

(2) Each order shall be elect its delegates from amidst their ranks in the numbers determined in Sections (), (), and () and in the mode of election to be prescribed by law.

??. Ecclesiastical order.— (1) The ecclesiastical order shall consist of seventy-five members, representing the clergy of His Most Christian Majesty’s Realms.

(2) Thirty members shall be elected by the clergy of France, thirty members by the clergy of England, and fifteen members by the clergy of Ireland

(3) The ecclesiastical provinces of each kingdom shall be the electoral units for this order, and the mode of election shall be prescribed by law.

??. Noble order.— (1) The noble order shall consist of seventy-five members, representing the nobility of His Most Christian Majesty’s Realms.

(2) Thirty members shall be elected by the nobility of France, thirty members by the nobility of England, and fifteen members by the nobility of Ireland.

(3) The provinces or counties of each kingdom shall be the electoral units for this order, and the mode of election shall be prescribed by law.