So this started out as a little idea heavily inspired by Belgium and my readings lately into Ancient Regime institutions and laws, but it got a bit out of hand:

Political Parties in the Dual Monarchy (1886)

Following the Charter Revolution of 1851, when the Commons and the Estates rose against King Henry X, forcing him to acquiesce to the restoration of traditional rights and liberties and introduce great institutional novelties like self-summoning estates and the Permanent Delegation of the 30 (1), tasked with overseeing the work of royal and governmental officials, a sort of comptroller office.

The Revolution introduced - restored according to its defenders - a complicated institutional set up across the kingdoms, while introducing a major novelty, a new body, the Joint Estates of the Realm. The French and English (and Welsh) electors each choose the same amount of commons' delegates, split between burgh seats and rural seats, while the Irish elect half of what the other two do. Then the nobility and the Church elect their own delegates, with the weight of their representation significantly reduced compared to the pre-1851 situation.

Since the Revolution, and particularly since the ascension to the throne of Edward VI, the former revolutionaries have split, as they by now the constitutional set up is secure and the old ideological and provincial differences have returned to the forefront of politics.

In addition to the traditional differences between the moderates and the liberals (themselves increasingly split between traditional or ‘doctrinary’ liberals and progressive ones) who have dominated politics since the Revolution, one has to add the traditionalists (the old Court Party) as well as the new political forces, the Irish trialists and the first workers’ organisations.

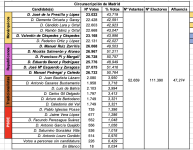

Following the hotly-contested 1885 election, when the Liberals under Walthère Frère-Orban were resoundingly defeated by the Moderates, as a result of the rejection by the voters of the anti-clerical policies of his cabinet, including the breaking of relations with Rome, the cutting of all funding for Catholic priests and the secularisation of all schools. In their stead, the Moderates came to power.

Government

Moderate Party - After 10 years out of power, the Moderates, led by Gathorne Hardy, have returned to power. In their agenda there is a push against the anticlericalism of the Frère-Orban years as well as some proposals to expand the franchise in the country seats (2).

In 1884, following the passing of the new liberal education laws, everyone expected a reaction, but no one - not even Moderates - expected the strength and resonance of the public backlash. Organised by parish priests and their flocks, and endorsed and funded by the Church, unprecedented marches on London and Paris were organised, hundreds of letters and petitions were addressed to the Estates, the Regent and the King calling on them to reject the legislation. The bishops in both France and England also spoke out in harsh tone condemning the move in spite of the government’s attempts to convince the Holy See to force them not to speak out.

This strong reaction has raised the stakes for the Moderates now in power, and it has greatly increased the internal battle between the parliamentary party - more moderate - and the leagues, clubs and circles that exist at the ground level and have close ties to the local gentry, agrarian leagues and the Church, which are far more clerical in outlook.

As a result, the Hardy cabinet is preparing legislation on the topic but is also quite divided. The majority of the parliamentary party, and roughly half the cabinet, led by Finance Minister H. H. Molyneux-Herbert (and supported by the Home Minister, Camille de Meaux) favour the repeal of the liberal laws and a return to the

status quo ante. Meanwhile, the Catholic associative world from which the party draws its supporters, a large minority of the parliamentary party, led by Hardy, favour a more radical repeal.

In these radical moderates’ view, the goal of the new bill is to entrench Catholicism in schools and allowing towns and villages to ban the opening of non-parochial schools by funding them and introducing religious requirements in teacher training curricula.

Little thought has been given to the disproportionate impact on Reformists and other dissenters, which may still come to bite them, not to mention the stir in high society, where the extremism of both Moderates and Liberals is raising the stakes in the country’s politics. Rumours of imposition of schooling languages will no doubt increase opposition in southern France where the attachment to their

langues d’oc is as strong as ever.

Unfortunately for them, the Moderates also face other issues now in power, inherited from the previous government. The economic situation in the country is not good, and budgetary restraints have been imposed, together with higher taxes. This already hurt the liberals and contributed to their downfall, and it is likely to also hurt the Moderates, particularly if the crisis starts to more directly affect the agricultural sector. As a result, agricultural relief and higher tariffs are being explored to protect the sector - and one of the party’s key constituencies.

Parliamentary Opposition

Liberal Party - the Liberals are in a rout. Their anticlericalism, overdone during the 1875-85 decade, has backfired. Their defence of provincial autonomy, free trade and the power of the Estates and parliaments is not enough of an ideological glue anymore, and anticlericalism, while unifying, is not exactly a vote-winner in either northern France or southern England. With the death of Henry X and the current reign of the boy king Edward, fears of attempted royal authoritarianism are not credible, and therefore they don’t unite the party either. Indeed, the great question for the party is the extension of suffrage.

The orthodox liberals led by Frère-Orban are opposed to any expansion (unless it is politically beneficial) and they struggle against the progressive liberals, led by Henri Brisson. The friction between the leaders and their factions has only increased as recriminations have gone up. Neither man is known as a compromiser, and the creation by the progressives of a separate organisation at the local and provincial level, and the establishment of a common platform, the ‘Liverpool Programme’, outlining nationalisations, welfare measures for workers and farmers, will only deepen the divide with the orthodox liberals, the strongest defenders of

laissez faire economics.

Lastly, there is the geographical divide. The Liberals are strongest in the cities all around, and particularly in the industrial centres of northern England, where there is a strong bourgeois element, but they are also markedly strong in the areas of Reformed majority in Auvergne, Dauphiné and south-western France, as well as in Wales and parts of north-western England. Here they can count on the support of rural voters and local potentates who support the liberals’ secular agenda to combat the Catholic clericalism of the moderates.

This divide strongly feeds into the intra-party conflict, as the urban bourgeois element in towns like Manchester or Liverpool fear the enfranchisement of the working classes (or indeed the radical lower middle classes) whereas the rural liberals are aware that broader enfranchisement could benefit them, or at least not menace their elections thanks to their position as local notables.

Regardless, in response to the Hardy cabinet’s new school law bill, the two fractions of the Liberal Party are united in launching a large campaign to oppose it. Gathering the signatures and voices of all the major cities’ mayors (London, Paris, Lyon, Marseille, Birmingham, Liverpool, Dublin, etc.), university deans and key intellectuals to petition the Regent to refuse to endorse the law and declaring that, if that fails, they will go to the Parliament (3) of Paris to ensure that the law is not published.

This legalistic and top-down approach that the liberals have contrasts to the grassroots organisation of the moderate and showcases the problems affecting the party and the risks to its long-term viability as a political entity if suffrage is extended and the liberals don’t adopt measures to attract a growing electorate - further feeding into the party’s ideological divide.

Irish Trialists - The Irish trialists are not a proper party - even by the lax standards of ‘party’ in late 19th century party politics - but rather a collection of Irish notables and Gaelic-speaking local and county officials, driven by a single unifying demand - the recognition of Ireland as an equal kingdom to England and France in the Dual Monarchy (the ‘Triune Monarchy’ as they call it), with equal participation in political affairs (unlike its current subordinate position to England) and equal representation to the other two kingdoms in the Joint Estates.

A growing movement in the Emerald Island, the trialists have gathered a great deal of support across the island’s religious divide based on their platform of equal representation and equal rights for the kingdom and its institutions, to put the island’s Commons and Lords on equal footing with its English equivalent.

The trialists have gathered support from across Ireland, but they are particularly strong in the more politically-aware Leinster province, where the Charter Revolution was more felt, and therefore where resentment at the lack of changes in the island is most strongly felt. Their advocacy for the use of Gaelic means that they are growing more support in the western half of the island, which resents the dominance of the English- or French-speaking elites in eastern Ireland.

Politically-speaking, their members could easily be either moderates or liberals (and indeed they are roughly evenly split), but their common pledge to fight for equal representation has meant that they tend to leverage their support to either major party, although their success so far as been limited. To showcase the broad support in the island for the trialist cause across the sectarian divide, there is a broad consensus that the movement needs to be led by two leaders, one Reformist (Parnell) and one Catholic (Gavan Duffy).

Anti-Revolutionary Party - The anti-revolutionaries are, in case it wasn’t clear from their name, the last legacy of the hardcore supporters of the pre-revolutionary legal settlement, with centralised royal government, two languages and restrained parliaments and estates. They represent a small faction, acting as ultra-moderates outdoing even the more extreme members of the Moderate Party.

Their platform is simple enough, they desire a return to the old system: legal and linguistic centralisation, noble ascendancy, closely relation between throne and altar and royal authoritarianism (taxation without consultation, appointment of urban and provincial officials, and the re-introduction of the

lettres de cachet and bills of attainder).

Regardless, after over 30 years of constitutional rule, the traditionalists are starting to make their peace with the system, particularly at the provincial level. These new anti-revolutionaries, who prefer to be referred to as ‘conservatives’, continue to espouse legally centralist views and an enshrined privileged role for the nobility and, especially, the Catholic Church in society. They are also strongly protectionistic. This has enabled them to survive as a political force in an otherwise hostile atmosphere.

Most of their members are elected (4) in the ‘noble’ seats to the Joint Estates, primarily from the extremely Catholic and conservative areas of Brittany and areas of intense sectarian tensions, like northern Provence.

Extra-parliamentary Opposition

Outside the Joint Estates, and for that matter nearly-all provincial estates, there is a brewing movement of the industrial working classes. In the large cities, in northern England and parts of northern France, industrial workers have formed socialist trade unions, mutual relief associations and all sorts of clubs (mutual support, education, sports, etc.), creating the first steps towards a working class organised subculture.

These organised workers and their associations are slowly beginning to interact with the broader political world, until now dominated by the aristocracy, the gentry and the urban bourgeoisie (whether patrician or burgher). This has been happening either by cooptation into the most progressive elements of the liberal camp or through the creation of Catholic workers’ associations, supported by the Church, and attempts to have “Catholic worker” independents run in urban elections, where the franchise requirements are lower (or non-existent in some cases).

However, there is growing dissatisfaction with the traditional parties, and inspired by the Burgundian and German models, union leaders and workers have began to create the first socialist parties to run for office at the local and provincial levels. These parties remain divergent in terms of their inspiration (philoclerical, anti-clerical, socialist, luddite, social Christian, liberal far-left, republican, etc.) and as such there not a single electoral force. And that is before entering into the sectarian divide or for that matter the tricky issue of trialism.

Nevertheless, the first congress of various forces is set to take place in 1887, as more and more leaders are becoming aware of the need to coordinate efforts. The outcome of the

1887 Workers’ Congress is very unclear, with a multitude of players.

Separately, “trouble" is stirring in southern France. Long proud of their history and aggrieved by the imposition of French over their langues d’oc, even if the practice has ceased, a

regionalist movement, of conservative and rural nature, is appearing in Languedoc, Aquitaine, Provence or the Dauphiné. So far its impact is heavily limited to provincial estates, but it is growing. These worries local liberals, as these provinces tend to represent their best strongholds, with southern French liberals starting to mimic the style of these regionalists.

—————

- Inspired by the Principality of Liege’s Tribunal of the 22.

- Also very Belgian in inspiration. The two main Belgian parties in the 19th century, the liberals and the Catholics, both believed broadly in wealth-based voting (indeed, it was enshrined in the Constitution) but liked to play with municipal tax rates to expand or restrict the franchise in the towns or in the countryside to benefit themselves. By the late 1890s, the Catholics were bigger believers in universal suffrage as they believed - rightly - that the Flemish countryside would vote for them. The liberals were more reluctant, knowing that their strength arose from the French-speaking urban middle and upper classes (in the late 19th century, this meant nearly-all urban middle and upper classes), but deeply divided between doctrinary liberals (opposed to universal suffrage) led by Frère-Orban and progressive liberals (favourable to universal suffrage and labour-liberal cooperation) led by Paul Janson.

- The Parlement de Paris, owing to its prestige and its composition has remained the key judicial organ in the monarchy, with its jurisdiction now extending to cover England and Wales as well as Ireland.

- The ‘noble’ seats to the Estates are elected by the nobility in a given province, although many of them are de facto attributed to the highest noble(s) of the province, with the remaining seat(s) allocated through an actual vote.

A similar system is used for the ‘ecclesiastical’ seats, which are allocated to specific ecclesiastical provinces, where some seats are elected by the members of abbeys, and others are elected by the bishops. In this cases, again, there is a certain tendency to vote respecting the hierarchical nature of the Church. Some have suggested introducing ecclesiastical seats to represent the Reformed churches, but nothing has come out of it - yet.