We're still trying to find reliable maps of the early South African elections, so those will be a while, but before then I do have a prologue of sorts to share. Yesterday I found a link from Wikipedia to a master's dissertation from the University of Cape Town, written in 1980 by Alan John Charrington Smith (I don't know which of those are first and last names, so I'm just typing in all of them in full), which goes into excruciating detail about the last few legislative elections in the Cape Colony before unification, starting in 1898 and ending with the colony's final election in 1908.

Starting in 1898 makes a degree of sense, because while one can definitely say clear political lines of disagreement existed before then, 1898 is really the first election to be fought with a real party system. The

Progressives, the Cape's first organised political party, was founded as a political vehicle for diamond magnate-turned-politician Cecil Rhodes, who had first been elected to the House of Assembly in 1880 and became Prime Minister ten years later. Rhodes has become relevant again in recent time owing to protests against his economic legacy in universities across the UK and South Africa, so he should need no further introduction, but to summarise briefly: his policies were staunchly pro-imperialist, both in the sense of supporting continued British rule and continued colonial expansion. Having made his money in the Big Hole of Kimberley, Rhodes was convinced it was his personal destiny and that of the British Empire to secure as much as possible of Africa's mineral wealth for itself, and for that purpose he founded the British South Africa Company to conquer and rule a large chunk of land in south-central Africa that he modestly christened Rhodesia. He was equally convinced that the black population's destiny was to provide cheap and expendable manual labour for Britain's colonial project, and to that end sponsored laws that raised the property qualification for voting (the Franchise and Ballot Act 1892) and imposed strict limits on the amount of land a black person could own while also dissolving the pre-existing communal land tenures held by indigenous villages (the "Glen Grey Act" of 1894). These laws are usually considered some of the first legislative precursors to apartheid, and did much to undermine the supposedly race-blind nature of the Cape electoral franchise.

However, Rhodes' influence did not extend across

all of South Africa, and this fact haunted him throughout his political career. In the Witwatersrand, which at the time was part of the independent South African Republic, a huge seam of gold had been discovered in 1886, and this brought a large influx of settlers from the Cape and other British colonies. To Rhodes, this was an intolerable situation: a potentially world-changing amount of precious metals, sitting

right outside his borders. Luckily, the strong presence of British workers and mining corporations in the Rand meant that the gold rush didn't necessarily threaten British dominance in the region, and in fact, might present an opportunity to seize control of the SAR and end the Boer self-government experiment once and for all. A plan was hatched whereby Leander Starr Jameson, the chief administrator of Southern Rhodesia, would lead a force of some 600 colonial militiamen into the SAR, where they would join up with an insurrection among the mineworkers in the Rand and seize control of the republic for Britain. Unfortunately, Rhodes and Jameson made no plans to actually bring about this insurrection, and it quickly became apparent that neither the miners nor the government in London had any interest whatsoever in supporting them. The "Jameson Raid" ended up an embarrassing debacle, with the force stopped dead by Boer commandos and its leaders taken prisoner.

There were some brief attempts to paint the Raid as an adventure and Jameson as a dashing colonial hero, but ultimately it was very hard to get past just how stupid it had all been. It had shown the SAR to be far more capable of defending itself than anyone had thought, and Kaiser Wilhelm sent a congratulatory telegram to President Kruger in which he seemed to offer his support if the republic ever needed to defend itself again. While Jameson was away, the Ndebele people launched an uprising of their own which would last eighteen months and claim many thousand lives. And back in Cape Town, not only was Rhodes forced to resign, the debates following the Raid led to the formation of the first-ever real opposition party in the colony.

The Cape was, of course, a very heterogeneous place then as now, and when the Voortrekkers left to establish the SAR and the Orange Free State, quite a lot of Afrikaners stayed behind, and continued to form the majority of the rural white population. Compared to the British settlers who dominated the cities and and the more recently annexed border regions, the Afrikaners were a lot less interested in the British colonial project - which isn't to say that they weren't racist, they just preferred not to take marching orders from London. The Jameson Raid raised particular ire, being directed against their "countrymen" in the SAR, and when Parliament was dissolved in 1898, the

Afrikaner Bond's Cape section decided it would go into the election in direct opposition to the Progressives. The Bond was an organisation that existed across what would become South Africa, and was devoted to securing the rights of Afrikaners - that is, white Dutch/Afrikaans-speaking people who considered themselves African rather than European - against British encroachment. It also sometimes advocated for the formation of a unified South African republic outside the British Empire, although this was not a goal actively pursued by its members in the Cape.

Rhodes was succeeded in office by J. Gordon Sprigg, veteran MP for East London, who had first been named Prime Minister in 1878 and now began his third stint in the role. Sprigg was, like Rhodes, an imperialist by inclination, but whereas Rhodes was a phenomenally wealthy mining speculator who stood for naked capitalism above all, Sprigg represented the interests of the Eastern Cape settlers who had first arrived from Britain in 1820 and who, in many ways, formed a totally distinct society from the rest of the colony. These areas had been conquered from the Xhosa over the course of several bloody "frontier wars" that lasted a whole century, starting under Dutch rule in the 1770s and ending with the surrender of the last guerrillas in the Amathole Mountains in 1879. Their inhabitants were still conscious of the military threat from the native population, however, and so they tended to favour a strong imperial connection as a way of defending their settlements. This was also Sprigg's position, and in fact he had presided over the defeat of those last Xhosa holdouts - however, he came to power with support from significant portions of the Bond as well as the Progressives, and his third premiership would be focused on more administrative issues.

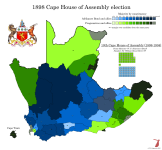

Specifically, Sprigg supported a project to reform the way the House of Assembly was elected to reduce rural overrepresentation, and thus weaken the influence of the Afrikaners, whom he regarded as another threat to British supremacy in the colony. Although his redistribution bill passed second reading, it caused significant tension within his coalition, and Bond-affiliated independent MP William Philip Schreiner ended up successfully pushing a motion of no confidence against Sprigg's government in May 1898. As a result, the lower house was dissolved mere months after the Legislative Council elections, and the elections would be fought on the same wildly unrepresentative boundaries as had existed beforehand. The seats ranged in size from Cape Division, with 8,122 registered voters, to Victoria East with 782 - both two-member seats, as were the majority of constituencies in place. The only exceptions were Cape Town and Kimberley, whose 7,798 and 5,674 voters respectively elected four members each, and the border constituencies of Mafeking, Tembuland and Griqualand East, with 605, 2,110 and 1,333 voters electing one member each. In total, the House counted 79 members, and as mentioned earlier, they were elected under a nominally race-blind franchise, with every adult male citizen of the colony owning at least £75 worth of property eligible both to vote and to stand for election. In practice, however, every single MP elected throughout the House's existence was white.

The 1898 campaign was spirited, with issues ranging from the Jameson Raid and the future of British imperialism in southern Africa to the urban-rural and British-Afrikaner divides (closely related to one another) within the colony itself. The Bond accused the Progressives of being supported by the colonial administration, while the Progressives accused the Bond of taking secret funding from the Boer republics and the Germans. The other big issue were food import duties, which the Bond strongly supported while the Progressives were forced to take a compromise position to avoid upsetting either the urban or rural parts of its base. There was also the issue of Rhodes, who continued to be identified with the Progressive Party even in retirement, bankrolling a large part of their campaign expenses and making sporadic statements about his readiness to return the moment the people called for him. This was questionably realistic, not least because he was in terrible health at this point and would die just a few years later, so the Progressives focused their efforts on defending the Sprigg ministry.

Their success in this would be very limited. The elections were held on different dates over the course of August 1898, and when the returns were completed on the 5th of September, the Bond and their independent allies had won 40 seats - the narrowest possible majority - in the House. Sprigg held on as Prime Minister initially, but in October lost another confidence vote, and Schreiner took office leading a Bond-dominated ministry. He immediately made clear his desire to work towards a peaceful understanding with the Boer republics to settle the issues that had precipitated the Jameson Raid, but this would bring him into conflict with the colony's new Governor, Sir Alfred Milner, whose intentions were entirely different...