NotDavidSoslan

Active member

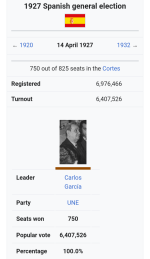

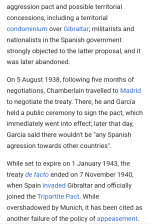

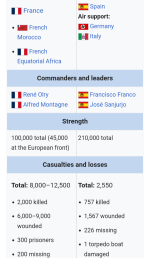

I used to make similar timelines in AH.com before leaving definitely, and hope to continue this style on this site. Since I called quits there due to the criticism and moving of a timeline where OSL was successful (and my tendency to often take criticism or disagreement as a personal offense) guarantee the Axis will lose the war, just two years later.

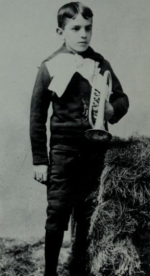

Early life of Carlos García (1881–1899)

Carlos Garcia in 1894, at the age of 13

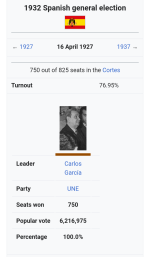

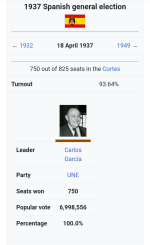

Carlos Perez García y Alejandro, the far right dictator of Spain between 1923 and 1947, was born in Fuentenava de Jábaga, itself located in the traditional region of Castile, on 17 March 1881. He belonged to the aristocratic Alejandro family, which was the biggest landowner in present-day Cuenca province, and part of a drinking, whoring and horse-loving aristocracy that ruled over one of the most starved and downtrodden agricultural classes in Europe.

His father, José Alejandro (1836–1910), was a general in the Spanish Army, who led troops in combat against the Carlist rebels in the 1870s war, and subsequently became a major friend and ally of kings Amadeo II and Alfonso XII. José Alejandro was a martinet who frequently appeared drunk in the village streets and had several illegitimate children; he beat up his wife and sons several times.

Carlos, named after Habsburg Emperor Charles V, was the second of José Alejandro's five legitimate children, and historians believe the physical abuse he suffered from his father shaped his authoritarian and violent character. As he grew older, he found comfort in reading about the history of Spain's imperial conquests in the 16th century, one of his father's few serious interests, and his rethorical style based itself on restoring the glories of the early modern period. Another characteristic García inherited was a contempt for the Carlists, whom he regarded as idealistic simpletons who wanted to return to a form of government that had already passed.

Garcia was homeschooled until age twelve, when his mother moved with him to the larger city of Cuenca, while José Alejandro stayed in the village. There, Garcia rejected the ethos of the class he belonged to, instead focusing on reading military history, collecting rocks, and helping his family. In 1895, Garcia was enlisted as a cadet in the Spanish Army, which fully entering it in 1899, one year after the defeat against the United States caused him to interest himself in politics as a far-right, modernizing and centralizing nationalist.

Carlos Garcia's military career (1899–1923)

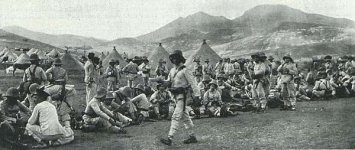

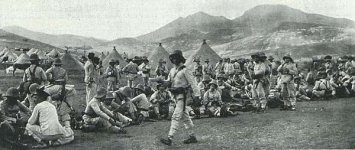

Garcia took part in the 1911 Kert Campaign, playing a key role in the Spanish victory.

Garcia became an infantryman who was repeatedly posted in mainland Spain, and the Canaries and Annobon; in the latter, he developed a racist view of Spain's remaining colonial subjects, whom he saw as unintelligent and barbarous, unlike the 16th-century Spanish conquistadors.

During Catalonia's Tragic Week of 1909, Carlos Garcia solidified his nationalist and authoritarian views, calling the Jacobin and anarchist strikers "Masonic Socialists" and unsuccessfully urging the king to violently put the strike down; during the Garcian era (1923–1947), strikes became illegal in Spain.

Garcia advocated for the military doctrine of the furious infantry assault, allowing his career to progress steadily. But what gave him attention was his role in the 1911 campaign against North African tribes: by then a major in the Spanish Army, he skillfully used mountain artillery and manhunting to destroy the rebels, capture or kill their leaders, and cut off their support. He also told military doctors to treat the illnesses of local civilians, predating "hearts and minds" campaigns of later insurgencies.

Thus, Garcia was promoted to a lieutenant colonel in 1913, colonel in 1916, and brigadier in 1920.

After 1918, post-World War I economic difficulties heightened social unrest in Spain. The Cortes under the constitutional monarchy seemed to have no solution to Spain's unemployment, labor strikes, and poverty. In 1921, the Spanish army suffered a major defeat in Morocco at the Battle of Annual, which discredited the military's North African policies, and Garcia came to support a gradual withdrawal from the region.

By 1923, deputies of the Cortes called for an investigation into the responsibility of King Alfonso XIII and the armed forces for the debacle. Rumors of corruption in the army became rampant, with Spaniards increasingly seeing Garcia as one of the few good officers.

Early life of Carlos García (1881–1899)

Carlos Garcia in 1894, at the age of 13

Carlos Perez García y Alejandro, the far right dictator of Spain between 1923 and 1947, was born in Fuentenava de Jábaga, itself located in the traditional region of Castile, on 17 March 1881. He belonged to the aristocratic Alejandro family, which was the biggest landowner in present-day Cuenca province, and part of a drinking, whoring and horse-loving aristocracy that ruled over one of the most starved and downtrodden agricultural classes in Europe.

His father, José Alejandro (1836–1910), was a general in the Spanish Army, who led troops in combat against the Carlist rebels in the 1870s war, and subsequently became a major friend and ally of kings Amadeo II and Alfonso XII. José Alejandro was a martinet who frequently appeared drunk in the village streets and had several illegitimate children; he beat up his wife and sons several times.

Carlos, named after Habsburg Emperor Charles V, was the second of José Alejandro's five legitimate children, and historians believe the physical abuse he suffered from his father shaped his authoritarian and violent character. As he grew older, he found comfort in reading about the history of Spain's imperial conquests in the 16th century, one of his father's few serious interests, and his rethorical style based itself on restoring the glories of the early modern period. Another characteristic García inherited was a contempt for the Carlists, whom he regarded as idealistic simpletons who wanted to return to a form of government that had already passed.

Garcia was homeschooled until age twelve, when his mother moved with him to the larger city of Cuenca, while José Alejandro stayed in the village. There, Garcia rejected the ethos of the class he belonged to, instead focusing on reading military history, collecting rocks, and helping his family. In 1895, Garcia was enlisted as a cadet in the Spanish Army, which fully entering it in 1899, one year after the defeat against the United States caused him to interest himself in politics as a far-right, modernizing and centralizing nationalist.

Carlos Garcia's military career (1899–1923)

Garcia took part in the 1911 Kert Campaign, playing a key role in the Spanish victory.

Garcia became an infantryman who was repeatedly posted in mainland Spain, and the Canaries and Annobon; in the latter, he developed a racist view of Spain's remaining colonial subjects, whom he saw as unintelligent and barbarous, unlike the 16th-century Spanish conquistadors.

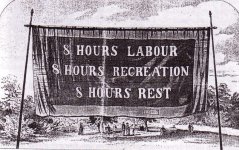

During Catalonia's Tragic Week of 1909, Carlos Garcia solidified his nationalist and authoritarian views, calling the Jacobin and anarchist strikers "Masonic Socialists" and unsuccessfully urging the king to violently put the strike down; during the Garcian era (1923–1947), strikes became illegal in Spain.

Garcia advocated for the military doctrine of the furious infantry assault, allowing his career to progress steadily. But what gave him attention was his role in the 1911 campaign against North African tribes: by then a major in the Spanish Army, he skillfully used mountain artillery and manhunting to destroy the rebels, capture or kill their leaders, and cut off their support. He also told military doctors to treat the illnesses of local civilians, predating "hearts and minds" campaigns of later insurgencies.

Thus, Garcia was promoted to a lieutenant colonel in 1913, colonel in 1916, and brigadier in 1920.

After 1918, post-World War I economic difficulties heightened social unrest in Spain. The Cortes under the constitutional monarchy seemed to have no solution to Spain's unemployment, labor strikes, and poverty. In 1921, the Spanish army suffered a major defeat in Morocco at the Battle of Annual, which discredited the military's North African policies, and Garcia came to support a gradual withdrawal from the region.

By 1923, deputies of the Cortes called for an investigation into the responsibility of King Alfonso XIII and the armed forces for the debacle. Rumors of corruption in the army became rampant, with Spaniards increasingly seeing Garcia as one of the few good officers.