prime-minister

Average electoral map enjoyer

- Location

- Cambridge

- Pronouns

- They/them

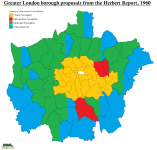

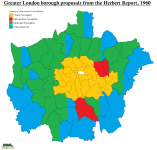

I had a little idea for something else London-related to map in between LCC elections. So, the 33 boroughs of Greater London came into existence to replace the 28 boroughs of the County of London and expand the capital region, but these boundaries were a second attempt. Initially the Royal Commision on Local Government in Greater London, known for short as the Herbert Commission after its chair Sir Edwin Herbert, proposed a very different set of boroughs covering an even larger area.

These boundaries would have created 52 Greater London boroughs out of the existing 28 boroughs, plus all the local authorities of Middlesex except Potters Bar, 17 from Surrey, 14 from Essex, 8 from Kent, and Barnet and Cheshunt from Hertfordshire. It's unclear what they would've been named as the committee never reached that stage, so I've instead elected to show the types of local authorities they were at the time as well as their boundaries.

The then-Local Government Secretary Keith Joseph turned these boundaries down both because they were considered to be undersized and because local pressure was mounting from several pro-Tory districts to prevent their inclusion. Ten districts would opt out of becoming part of Greater London- Chigwell in Essex, Cheshunt in Hertfordshire, Staines and Sunbury in Middlesex (which became part of Surrey), and Walton and Weybridge, Esher, Epsom and Ewell, Banstead, and Caterham and Warlingham in Surrey. From what I gather, Epsom and Ewell opted out right at the last minute, and for a while after the other districts had opted out was meant to be part of Kingston-upon-Thames.

Another part of why the commission had to go back to the drawing board was that several of these boundaries didn't solve the problems this reorganisation was meant to fix. For instance, North Woolwich would've stayed in Woolwich despite geographically being part of East Ham and so having a ridiculous amount of conflicting local government agencies controlling it, and the proposed borough combining Holborn, Finsbury and Shoreditch had a combined population of under 95,000.

On the flipside, you can tell there's a lot of parts of this that were in line with what the boroughs actually wanted- West Ham and East Ham staying separate, Hornsey and Wood Green merging with Southgate instead of Tottenham, Hayes and Harlington sharing a borough with Southall instead of Uxbridge, and Wembley and Wllesden remaining separate. It's also a bit funny to me how Wandsworth getting sliced apart and absorbing Battersea was something proposed this early considering it was the only existing borough to be split instead of merged.

These boundaries would have created 52 Greater London boroughs out of the existing 28 boroughs, plus all the local authorities of Middlesex except Potters Bar, 17 from Surrey, 14 from Essex, 8 from Kent, and Barnet and Cheshunt from Hertfordshire. It's unclear what they would've been named as the committee never reached that stage, so I've instead elected to show the types of local authorities they were at the time as well as their boundaries.

The then-Local Government Secretary Keith Joseph turned these boundaries down both because they were considered to be undersized and because local pressure was mounting from several pro-Tory districts to prevent their inclusion. Ten districts would opt out of becoming part of Greater London- Chigwell in Essex, Cheshunt in Hertfordshire, Staines and Sunbury in Middlesex (which became part of Surrey), and Walton and Weybridge, Esher, Epsom and Ewell, Banstead, and Caterham and Warlingham in Surrey. From what I gather, Epsom and Ewell opted out right at the last minute, and for a while after the other districts had opted out was meant to be part of Kingston-upon-Thames.

Another part of why the commission had to go back to the drawing board was that several of these boundaries didn't solve the problems this reorganisation was meant to fix. For instance, North Woolwich would've stayed in Woolwich despite geographically being part of East Ham and so having a ridiculous amount of conflicting local government agencies controlling it, and the proposed borough combining Holborn, Finsbury and Shoreditch had a combined population of under 95,000.

On the flipside, you can tell there's a lot of parts of this that were in line with what the boroughs actually wanted- West Ham and East Ham staying separate, Hornsey and Wood Green merging with Southgate instead of Tottenham, Hayes and Harlington sharing a borough with Southall instead of Uxbridge, and Wembley and Wllesden remaining separate. It's also a bit funny to me how Wandsworth getting sliced apart and absorbing Battersea was something proposed this early considering it was the only existing borough to be split instead of merged.