And now it's time to return to German municipal elections, today featuring Köln, the fourth-largest city in Germany and the largest city in (though not the capital of) its largest state.

Köln is one of the oldest cities in Germany, having been founded by the Romans under the name

Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium sometime during the reign of Emperor Claudius (after whose wife it was named). As capital of Germania Inferior, it grew to be a substantial city even then, and retained this status under the Franks, who placed an archbishopric in the city. The Prince-Archbishops of Köln would gain one of the seven Electoral seats of the Holy Roman Empire, and their land holdings stretched across much of the lower Rhineland and the Sauerland to the east - but did not include the city itself, which was made a free imperial city in 1475 after having been

de facto independent of episcopal rule for about two hundred years. This arrangement carried on until the French Revolution, at which point Köln fell inside the "natural borders" of France and became a sub-prefecture in the department of the Roer. After Napoleon's defeat, the Rhineland was given to Prussia, which was thought better suited to guarding the region against renewed French attacks, but the attacks never came, and the Catholic Rhineland chafed under Protestant Prussian rule. It became a stronghold of the Centre Party, Köln being no exception, with Centre stalwart and future Chancellor Konrad Adenauer ruling the city throughout the Weimar era.

The city gained essentially its current shape during the interwar period, with the industrial city of Mülheim/Rhein (not to be confused with Mülheim/Ruhr) on the right bank of the Rhine being annexed in 1914 and the Worringen region north of the city coming in in 1922. This tipped the balance of city politics toward the left as the National Socialist dictatorship ended, and the SPD would rule from 1956 until 1999 without exception. In 1975, a further round of incorporations saw (among others) the cities of Porz and Wesseling, south of the city centre, brought into Köln, but Wesseling would secede again after eighteen months. This rendered the city a bit more favourable for the CDU, but happened to coincide with the growth of the Green Party, which would find a particular stronghold in Köln, in a state otherwise infamous for shafting minor parties.

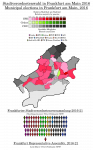

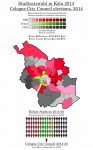

NRW is one of two states (the other being Schleswig-Holstein) to use a mixed-member system for electing municipal councils, and the only one to do it with a consistent system of single-member wards. As such, out of the 90 seats on Köln's city council, 45 are elected in single-member constituencies, which gives us a nice overview of which parties are strong where - broadly speaking, the right bank and the north of the left bank support the SPD, the south of the left bank supports the CDU, and the Greens are strong in the inner city and the area around the university to the southwest. Unlike in Bundestag elections (and most state elections), the voter only casts a single vote that goes to both his/her local candidate and the connected party list - unlike in B-W, there are party lists to determine who gets elected outside the Direktmandaten.

There used to be a 5% threshold to go with the mixed-member system - this was highly unusual for a municipal election system in Germany, and as such the rule was struck down after the 1994 elections by a Constitutional Court ruling. Just in time, as it turned out, for some new parties to appear on the scene representing some of the... less mainstream sides of politics. On the one hand, there was the PDS (as it was then called), which won two seats in 1999 and grew to six in 2014. On the other hand, there is the

Pro-Bewegung, which is a hard-right Islamophobic grouping, and likely precursor to PEGIDA, which was founded after 9/11 and counts Köln as its particular home. The

Bürgerbewegung pro Köln won four seats straight away in 2004, and while hobbled by the rise of the AfD, continued being represented on the council until its dissolution in 2018.

On the whole, the 2014 elections were somewhat uneventful. The 90s had seen a resurgence for the CDU, same as in a lot of German cities, but this definitively ended in 2009 when the party went below 30% for the first time since its founding. The SPD were able to claw back to a narrow first place, keeping it in 2014, but the Greens are now strong enough to control which of the

Volksparteien rules Köln.

There are separate mayoral elections in NRW, as in most German states, and these were rather more eventful than the council elections. Incumbent SPD mayor Jürgen Roters, who had won office in 2009 amidst a corruption scandal involving the CDU leadership and a local savings bank, was later revealed to have benefitted from the same corrupt arrangement. The so-called

Kölscher Klüngel ("Köln clique", a form of mutual cronyism between politics and business regarded as particular to Köln) came into public discussion yet again, and there was a yearning for someone from outside politics. In 2015, as Roters' term came up, the CDU, FDP and Greens announced their mutual support for lawyer and ex-deputy mayor of Gelsenkirchen Henriette Reker, a political independent, to succeed him. She would win the backing of the Free Voters and the independent electoral association "Deine Freunde" ("Your Friends" - a greenish NIMBY outfit), and romped to victory with 52% of the vote in the first round. Perhaps illustrating the depth of protest sentiment, the candidate of Die PARTEI came in third with 7%.