Fantastic work Max, really interesting to imagine the transport what-ifs there.

-

Hi Guest!

The costs of running this forum are covered by Sea Lion Press. If you'd like to help support the company and the forum, visit patreon.com/sealionpress

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Max's election maps and assorted others

- Thread starter Ares96

- Start date

U.S. House 1968

- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

And another project, this time an old one I was reminded of by my rail mapping and decided to finish off.

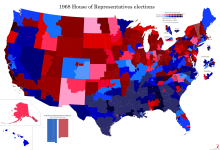

In the National Atlas of the United States, in addition to a large selection of general reference maps and the rail map I've been using, there is a map of congressional districts in use as of the 1968 election. Putting this on the @Chicxulub county basemap gives us a very nice view of how legislative elections in the US looked at the time, and indeed for most of the Cold War era.

This election was held at the same time as the 1968 presidential election, which is usually considered one of the great realigning elections in US history - Richard Nixon was able to win a majority in the Electoral College, partly off of the old Republican strongholds in the Midwest and West, but also thanks to the Republicans breaking into the old Democratic strongholds in the South. The only former Confederate state that voted for Hubert Humphrey in 1968 was Texas, probably in large part due to the influence of outgoing President Lyndon B. Johnson. Because, while the Republicans won several southern states, another four voted for the third-party campaign of George Wallace, who was nominated in place of Humphrey by several state Democratic parties in the Deep South. In Congress, however, very little trace of this was seen: the South remained very staunchly Democratic, while much of the rest of the country was split between solid Republican and solid Democratic districts.

The reason for this is relatively simple: in 1968, the parties were still ideologically incoherent, with a large liberal wing in the Republican Party and a very large conservative wing in the Democratic Party. A Republican from Massachusetts could easily be substantially to the left of a Democrat from Mississippi, and once elected, members tended to form coalitions based more on ideological affiliation than party affiliation (especially between conservatives in the two parties). And while the parties still mattered in some ways - notably, their relative strength in the House determined who could set the legislative agenda and who would get leading positions on committees - the way this worked also rewarded those representatives from each party who had the highest seniority. This meant that a district whose member had served longer would get more influence in Washington, and by extension, that keeping an incumbent in office was almost always advantageous. For this reason, I've marked the few seats that didn't have an incumbent representative with asterisks, to let you see where this did and didn't correlate with the few relatively close races.

In the National Atlas of the United States, in addition to a large selection of general reference maps and the rail map I've been using, there is a map of congressional districts in use as of the 1968 election. Putting this on the @Chicxulub county basemap gives us a very nice view of how legislative elections in the US looked at the time, and indeed for most of the Cold War era.

This election was held at the same time as the 1968 presidential election, which is usually considered one of the great realigning elections in US history - Richard Nixon was able to win a majority in the Electoral College, partly off of the old Republican strongholds in the Midwest and West, but also thanks to the Republicans breaking into the old Democratic strongholds in the South. The only former Confederate state that voted for Hubert Humphrey in 1968 was Texas, probably in large part due to the influence of outgoing President Lyndon B. Johnson. Because, while the Republicans won several southern states, another four voted for the third-party campaign of George Wallace, who was nominated in place of Humphrey by several state Democratic parties in the Deep South. In Congress, however, very little trace of this was seen: the South remained very staunchly Democratic, while much of the rest of the country was split between solid Republican and solid Democratic districts.

The reason for this is relatively simple: in 1968, the parties were still ideologically incoherent, with a large liberal wing in the Republican Party and a very large conservative wing in the Democratic Party. A Republican from Massachusetts could easily be substantially to the left of a Democrat from Mississippi, and once elected, members tended to form coalitions based more on ideological affiliation than party affiliation (especially between conservatives in the two parties). And while the parties still mattered in some ways - notably, their relative strength in the House determined who could set the legislative agenda and who would get leading positions on committees - the way this worked also rewarded those representatives from each party who had the highest seniority. This meant that a district whose member had served longer would get more influence in Washington, and by extension, that keeping an incumbent in office was almost always advantageous. For this reason, I've marked the few seats that didn't have an incumbent representative with asterisks, to let you see where this did and didn't correlate with the few relatively close races.

Excellent work Max, adding a symbol for incumbency is a nice idea as it matters A LOT in US congressional politics, especially in this era.And another project, this time an old one I was reminded of by my rail mapping and decided to finish off.

In the National Atlas of the United States, in addition to a large selection of general reference maps and the rail map I've been using, there is a map of congressional districts in use as of the 1968 election. Putting this on the @Chicxulub county basemap gives us a very nice view of how legislative elections in the US looked at the time, and indeed for most of the Cold War era.

This election was held at the same time as the 1968 presidential election, which is usually considered one of the great realigning elections in US history - Richard Nixon was able to win a majority in the Electoral College, partly off of the old Republican strongholds in the Midwest and West, but also thanks to the Republicans breaking into the old Democratic strongholds in the South. The only former Confederate state that voted for Hubert Humphrey in 1968 was Texas, probably in large part due to the influence of outgoing President Lyndon B. Johnson. Because, while the Republicans won several southern states, another four voted for the third-party campaign of George Wallace, who was nominated in place of Humphrey by several state Democratic parties in the Deep South. In Congress, however, very little trace of this was seen: the South remained very staunchly Democratic, while much of the rest of the country was split between solid Republican and solid Democratic districts.

The reason for this is relatively simple: in 1968, the parties were still ideologically incoherent, with a large liberal wing in the Republican Party and a very large conservative wing in the Democratic Party. A Republican from Massachusetts could easily be substantially to the left of a Democrat from Mississippi, and once elected, members tended to form coalitions based more on ideological affiliation than party affiliation (especially between conservatives in the two parties). And while the parties still mattered in some ways - notably, their relative strength in the House determined who could set the legislative agenda and who would get leading positions on committees - the way this worked also rewarded those representatives from each party who had the highest seniority. This meant that a district whose member had served longer would get more influence in Washington, and by extension, that keeping an incumbent in office was almost always advantageous. For this reason, I've marked the few seats that didn't have an incumbent representative with asterisks, to let you see where this did and didn't correlate with the few relatively close races.

View attachment 72284

It's also noteworthy as taking place after the VRA so the old de-facto malapportionment is gone (I think all states had been forced to redistrict by 1968?) while gerrymandering hasn't adapted yet so most of these boundaries actually look halfway reasonable - which itself looks very strange compared to a modern US House map.

- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

I believe so, yes - there certainly were a lot of redistrictings before this election, and places like Birmingham or Atlanta lead me to suspect population balances were generally alright.It's also noteworthy as taking place after the VRA so the old de-facto malapportionment is gone (I think all states had been forced to redistrict by 1968?) while gerrymandering hasn't adapted yet so most of these boundaries actually look halfway reasonable - which itself looks very strange compared to a modern US House map.

Plus, while this was after the Reapportionment Revolution, this was before the rulings that determined that, outside of vanishingly specific cases, each state's congressional districts were supposed to have a population within one person of another, meaning that you could actually go with a, say, 1% deviation from the target in order not to have to split a random county with three thousand people in it.

Maybe it’s a bit impossible but if you think it would be possible to make a map showing, instead of D or GOP, something more like “liberal/conservative/Dixiecrat”? I’d assume the press at the time would usually give (imprecise?) information about it?

Last edited:

msmp

Insert Pine Tree Flag Here

- Pronouns

- he/him/his

Bare minimum, for the winners/incumbents it can usually be determined by a brief glance at their wiki page.Maybe it’s a bit impossible but si you think it would be possible to make a np showing, instead of D or GOP, something more like “liberal/conservative/Dixiecrat”? I’d assume the press Errol the time would usually give (imprecise?) information about it?

True story: at one time during the late 1970s and early 1980s, since the Democratic Party had a stranglehold on the House, the three tv networks essentially projected control of the House as "liberal" or "conservative" based on their read of members' ideologies, since the partisan majority was meaningless (even the most conservative Democrat/Dixiecrat would fall in line to support the Speaker in organizational matters or the vote for the Speakership; see Tip O'Neill never having trouble keeping his gavel for proof of concept).

I have a congressional guide from 1978 which actually rates each congressman or senator on 10 shibboleth questions (e.g. abortion) just because it was so difficult in that era to put people into camps. I suppose Max could do it by caucus membership, but there is some overlap.Maybe it’s a bit impossible but if you think it would be possible to make a map showing, instead of D or GOP, something more like “liberal/conservative/Dixiecrat”? I’d assume the press at the time would usually give (imprecise?) information about it?

prime-minister

Average electoral map enjoyer

- Location

- Cambridge

- Pronouns

- They/them

Thinking about it, something like that would be really beneficial for the early Reagan era elections to classify who were considered 'Boll Weevil Democrats' and 'Gypsy Moth Republicans' (iirc that's what Dems who generally supported Reaganomics and GOP members who were generally opposed to it were called, right?). There's a tendency to paint it in monolithic geographic terms and I'd love to see just how accurate those terms were on an electoral map.I have a congressional guide from 1978 which actually rates each congressman or senator on 10 shibboleth questions (e.g. abortion) just because it was so difficult in that era to put people into camps. I suppose Max could do it by caucus membership, but there is some overlap.

- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

My gut feeling is that it’s going to be hard to work out a conclusive way to map those affiliations - in general I imagine it was more like the Supreme Court today, where you generally have some idea of who’s a liberal and who’s a conservative, but also most of them have at least a couple of issues where their position is more heterodox or even goes directly against their “bloc”. I suppose you could map votes on crucial left-right issues, or (as @Thande says) caucus memberships within each party, but in general I feel like this is going to be more effort than it’s worth for me. On top of which I’ve already moved on to the era I really wanted to cover, and the first map of that should be done fairly soon.

msmp

Insert Pine Tree Flag Here

- Pronouns

- he/him/his

This is fundamentally true, and there's a lot of researchers in American political science who have spent years trying to find a single coherent system of mapping the ideological maneuvering of the Democratic coalition from the 1950s to the 1990s. Part of the problem is exactly what you're saying, but another part is that there wasn't any real consistency as to what issues the right-wing members of the party actually broke on. For a lot of them, they were similar to a kind of "red Tory" on steroids in a Canadian context: social conservatives who were otherwise supportive of progressive economic policy a la the New Deal or even LBJ's Great Society. But there were also a lot who went the entire other direction on it, as social moderates who would have voted to legalize feudalism if they thought it would win them the next Dem primary.My gut feeling is that it’s going to be hard to work out a conclusive way to map those affiliations - in general I imagine it was more like the Supreme Court today, where you generally have some idea of who’s a liberal and who’s a conservative, but also most of them have at least a couple of issues where their position is more heterodox or even goes directly against their “bloc”. I suppose you could map votes on crucial left-right issues, or (as @Thande says) caucus memberships within each party, but in general I feel like this is going to be more effort than it’s worth for me. On top of which I’ve already moved on to the era I really wanted to cover, and the first map of that should be done fairly soon.

Then you also get the people who were ideologically consistent as right-wing, but then had one or two issues where they were just wildly to the left of most of the party. Zell Miller comes to mind in that regard, especially in his second act as a Senator. Left as they came on education access, but right-wing everywhere else.

And then you had Larry McDonald, who was synonymous with the John Birch Society and was once ranked the most conservative member of Congress in the modern (1937-) era. The less said about him the better, though.

prime-minister

Average electoral map enjoyer

- Location

- Cambridge

- Pronouns

- They/them

That's kind of a thing across conservatives in the Anglophone world from after WW2 to the 1980s, thinking about it- you mentioned red Tories, but the British Tories were also famous for mostly toeing the line of the postwar consensus until Thatcher et al. while almost all being very socially conservative (and now I'm wondering if a map of 'wets' and 'dries' in the early 1980s would look like). From what I gather Australia had (has?) a slightly more coalesced thing around the Coalition parties, and NZ gets even more complicated with how the right-wing ideology eventually bled into Labour through Rogernomics.This is fundamentally true, and there's a lot of researchers in American political science who have spent years trying to find a single coherent system of mapping the ideological maneuvering of the Democratic coalition from the 1950s to the 1990s. Part of the problem is exactly what you're saying, but another part is that there wasn't any real consistency as to what issues the right-wing members of the party actually broke on. For a lot of them, they were similar to a kind of "red Tory" on steroids in a Canadian context: social conservatives who were otherwise supportive of progressive economic policy a la the New Deal or even LBJ's Great Society. But there were also a lot who went the entire other direction on it, as social moderates who would have voted to legalize feudalism if they thought it would win them the next Dem primary.

Then you also get the people who were ideologically consistent as right-wing, but then had one or two issues where they were just wildly to the left of most of the party. Zell Miller comes to mind in that regard, especially in his second act as a Senator. Left as they came on education access, but right-wing everywhere else.

And then you had Larry McDonald, who was synonymous with the John Birch Society and was once ranked the most conservative member of Congress in the modern (1937-) era. The less said about him the better, though.

I have access to this now so I can give a bit more detail. Every senator, representative and governor (organised in the book by state not house, because America) has the following:I have a congressional guide from 1978 which actually rates each congressman or senator on 10 shibboleth questions (e.g. abortion) just because it was so difficult in that era to put people into camps. I suppose Max could do it by caucus membership, but there is some overlap.

- Electoral career, educational background, pre-political career, religion

- Office addresses

- Committee memberships

- Group ratings. Various pressure groups rate each of them out of 100 for how in line they are with their views. We only ever seem to hear about this today with respect to guns or abortion. See below for the groups.

- Key votes, FOR, AGN or DNV. These vary from person to person but might include authorisation of the B-1 bomber, arms sales to Pinochet, splitting up the oil companies, no-fault divorce, federal funding for abortion.

- Election results

- For congressmen, a write-up about their districts at the time.

Here are the groups giving the ratings out of 100-

ADA: Americans for Democratic Action (liberal; Wiki says it faded from prominence after Nixon's victory in 1968, but it's still being quoted here in 1978)

COPE: Committee on Political Education (labour organising for political action; doesn't rate a Wiki article, had to look it up on the University of Maryland site)

PC: Public Citizen (Consumer advocacy, progressive; founded by Ralph Nader but they broke up after 2000)

RPN: Mysteriously not mentioned in the abbreviations glossary? Their numbers also usually seem to be like around 40-65 for everyone and change a lot year-on-year so I can't even tell from context what they're rating people on.

NFU: National Farmers' Union

LCV: League of Conservation Voters

CFA: Consumer Federation of America

NAB: National Association of Businessmen

NSI: National Security Index of the American Security Council

ACA: Americans for Constitutional Action (Conservatives, especially social conservatives. This is probably the most meaningful one for picking out conservative southern Democrats. Not sure how they would feel about their acronym now being applied to Obamacare...)

NTU: National Taxpayers' Union (fiscal conservatives, no you don't say, probably extremely dodgy like all pressure groups that mention paying anything in their name).

It is rather striking that there's no specific groups for guns or abortion as one is accustomed to nowadays, and a lot more focus on consumer advocacy. The book quotes the ratings on an annual basis, although not all groups made the rating that often.

U.S. House 1912

- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

I'm very glad this latest change in theme seems to have brought some interest, because there's more congressional maps coming.

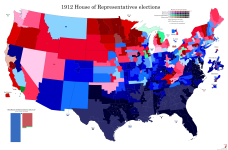

We start this series in 1912, an interesting year for a number of reasons. Firstly because it was the last really properly three-cornered presidential race in U.S. history - in 1968, while Wallace ran a nationwide campaign with a nationwide party, he got very limited traction outside the South and even he would probably have candidly admitted that he wasn't trying to win the presidency outright, and in 1992, Perot got a reasonably impressive nationwide voteshare but won no states and wasn't really close to winning more than a handful of electoral votes. In 1912, however, there were three candidates heading nationwide organised political parties who all had significant pockets of strength around the country, although it was pretty clear from the beginning who was going to win.

The Progressive Era, which was at or near its absolute zenith in 1912, was a weird period in American political history. Generally, most American party systems consist of one "active" political party, whose formation or adoption of a new program signals the start of the party system, and a "reactive" party, who form as a broad coalition in opposition to the active party and tend to be a lot less ideologically coherent. From 1860 until about 1890, the Republicans had been the active party in American politics, formed on a platform of opposition to slavery, American nationalism and an economic policy that combined government aid for economic development (particularly rural economic development) with protectionist trade policy and strong support for big business, and gathering a coherent bloc made up of businessmen, small-town notables, farmers and Protestant churches. Opposing them were the Democrats, left over from the previous party system, and combining their old Jacksonian populist element with urban machines, Catholics and immigrants as well as the white supremacist bloc in the South, which by 1890 was completely and utterly dominant across most of the region. It was an extremely weird amalgam of interests, but through most of the period, control was maintained by a pro-business faction known as the Bourbon Democrats, who ensured that the party mostly differed from the Republicans in wanting lower tariffs and a weaker federal government. The main divide among voters had less to do with ideology and more to do with the legacy of the Civil War - if you or your family fought for the Union or otherwise identified with its cause, you probably voted Republican, and if you didn't (whether that was because you disagreed with Lincoln's conduct in office, because you were on the Confederate side, or because you came to America after 1865 and didn't have a stake in the matter), you probably voted Democratic.

By the 1890s, however, things were slipping. Grover Cleveland's presidency, usually regarded as the peak of the Bourbon Democrats, resulted in new battle lines being drawn, with a number of anti-corruption Republicans breaking with the party to support Cleveland against James G. Blaine, who was widely suspected of having sold favours to railroads during his time as Speaker of the House. On the Democratic side, meanwhile, Cleveland's conservatism drew the ire of the populist wing of the party, and after the Panic of 1893, his critics were able to take full control of the party. The 1896 DNC, dominated by southern and western anti-Bourbon interests, resulted in the nomination of William Jennings Bryan, a young firebrand from Nebraska who seemed to run against everything Cleveland stood for. The nascent People's Party, an organisation of farmers and rural workers in the West who had won a few electoral votes in 1892 and had a decent-sized bloc of seats in the House of Representatives, cross-endorsed Bryan, and the stage seemed set for a new realignment along something more like what we might recognise today as left-right lines.

Yet this never happened. Perhaps it was too early in 1896, a time when many thousands of Civil War veterans were still alive and the legacy of the conflict still shaped politics, for the political divide created by it to simply go away. Regardless, the Democrats and Republicans continued to operate, and indeed still continue to operate to this day. Bryan's crusade against the bankers and plutocrats who would "crucify mankind upon a cross of gold" did not convert the Democratic Party into a vehicle for progressive reform, and indeed conflict would continue to rage between his faction and the legacy Bourbons right up until FDR forced them together to combat the Great Depression.

Instead, the Progressive Era would come to be defined by these internecine struggles between progressive and conservative forces within each party, and it was a Republican who would implement most of the key progressive demands. In 1900, as William McKinley ran for re-election, he was persuaded to accept Governor of New York, and leading progressive Republican, Theodore Roosevelt as his running made. This was done partly as a sop to progressives within his own party, partly to neutralise Bryan's message in his second run for the presidency, and partly because the New York Republican machine wanted to neutralise Roosevelt by kicking him upstairs to a largely-powerless federal office. This backfired spectacularly the next year, when McKinley was assassinated while visiting the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, and Roosevelt assumed the presidency. He would serve for almost two full terms, winning re-election in 1904 and retiring in 1908, handing power to his hand-picked successor William Howard Taft.

Taft would go on to alienate Roosevelt and his progressive faction in office. There's been raucous historical debate over how much of a conservative Taft actually was - he continued many of Roosevelt's initiatives, and would later argue he'd gone further to break up trusts than Roosevelt had. According to this line of argument, Roosevelt moved to the left after his presidency, arguing for a "New Nationalism" which included things like social insurance, inheritance taxes, an expanded right to strike and campaign finance regulations, and while Taft continued to implement the agenda of Roosevelt's presidency, he did not support his mentor's new tack. According to Roosevelt's supporters, meanwhile, Taft had been captured by big business and was now a full-throated enemy of their movement. Wherever the truth lay - and there was probably some truth to both sides of the argument - Taft and Roosevelt became the standard-bearers for the opposing factions of the Republican Party heading into the 1912 election.

It pretty quickly became clear that the Republican state organisations mostly favoured Taft's more moderate line, and that the convention would be dominated by the conservative faction. Roosevelt's supporters blamed this on the large Southern contingent at the convention, which was both firmly conservative and hugely overrepresented relative to the number of Republican voters in those states. Disputes over this led most Roosevelt supporters to abstain on the nomination ballot, and when Taft won the nomination on the first ballot, they walked out of the convention. They hastily organised a convention for a new "Progressive Party", which nominated Roosevelt unanimously and approved a platform, the "Contract with the People", which essentially copied Roosevelt's "New Nationalist" agenda. There was one notable exception - antitrust measures, which had probably been the single most important progressive hallmark of Roosevelt's presidency, was struck from the platform in favour of vague language about "strong regulation". This was blamed on the influence of George Walbridge Perkins, one of the party's key financiers and an employee of J. P. Morgan whose progressivism included arguments for "the Good Trust", and a number of leading progressives declared the new party a lost cause before it really got going.

Nevertheless, Roosevelt was still personally popular, and a large number of rank-and-file Republicans defected to his campaign, giving him a momentum that easily overpowered Taft's official Republican campaign. Whatever Taft's personal politics might have been, the formation of the Progressive Party left the GOP firmly in conservative hands, and its campaign focused on attacking Roosevelt as a dangerous radical who would change America beyond all recognition and/or an inveterate egotist who was only running to satisfy his vanity and sabotage Taft. It wasn't a very effective strategy, and Taft, as the only status quo candidate in the race, had very few real arguments to sway voters.

But, of course, there was also a Democratic campaign. And surprisingly enough, even as the Republicans were tearing themselves apart, the Democrats appeared more united than ever. There had been a clamour for Bryan to run again - his fourth heave - but the man himself refused, believing the one thing that could hurt the party's chances at this point would be nominating a three-time loser. This meant a bitterly contested convention, a Democratic Party tradition in the making, which ended up nominating Woodrow Wilson, a southerner who moved to New Jersey to take up a professorship at Princeton University - he'd served both as president of the university and governor of the state by the time of his nomination. Wilson was known as a reformer who took an intellectual approach to politics and shared many progressive goals, but he also appealed to conservatives in the South because he came from there and remained outrageously racist even by the standards of the time. As President, even as his administration made strides on some progressive issues, the federal government was segregated, and the Southern tradition of lynchings and race riots spread throughout the United States with the apparent blessing of the White House.

Because, in case you hadn't already figured it out, the main effect of the Republican split was to give Wilson a clear run for the White House. He won 40 of 48 states and 435 electoral votes, the largest number ever recorded, despite only gaining some 41% of the popular vote. Roosevelt won another six states, mostly in the West but also including Michigan and Pennsylvania, while Taft won only Vermont and Utah.

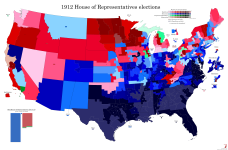

Of course, the map I've made isn't of the presidential election - you can find good maps of that in other places already - but of the congressional election that accompanied it. By 1912, all states elected their congressmen on the same day they elected the President, except Vermont and Maine, which elected their ones alongside state elections in September. This is the origin of the saying that "as Maine goes, so goes the nation" - it wasn't that Maine's election results tended to match those across the country, it was that you could read political trends from their elections because they literally voted two months before everyone else.

1912 was the first election after the 1910 Census, and also the first after Arizona and New Mexico were admitted to the Union. The Census showed a population of 92 million, up from 76 million in 1900, and the Apportionment Act of 1911 determined that 435 seats in the House of Representatives would be adequate to represent this population. For reasons we'll no doubt get to, this is still the size of the House, even though the country has more than tripled in population since then. Anyway, this represented an increase of 44 seats from the previous election, or 41 counting the three seats given to Arizona and New Mexico in the interim, and with around 210,000 inhabitants per seat, it still represented the largest population-to-seat ratio in U.S. history up until that point. Of course, while the states were technically required to make their electoral districts compact, contiguous and equal, in practice these rules were very loosely observed in a time before the Voting Rights Act.

This would be demonstrated in more ways than one. While, again, states were required by the Apportionment Act to draw as many districts as it had representatives, the Act also allowed for representatives to be elected at-large (that is, by the entire population of the state) as needed until redistricting laws could be passed. An astonishing fourteen states did this, with Montana, Idaho and Utah electing their two-seat delegations statewide, while another eleven states used a combination of statewide and district elections. Most egregious in this regard were Oklahoma, which gained three new seats but kept using its five districts drawn in 1906, and Pennsylvania, which gained four seats but kept using its 32 previous districts. Even more astonishingly, Pennsylvania would keep doing this for ten years.

As with the presidential race, the congressional elections of 1912 were a blowout for the Democrats. Even though the House grew by 41 seats, the Republicans suffered a net loss of 28, and the Democrats won a two-thirds majority of seats. Their gains included inroads into strongly Republican regions like Pennsylvania, northern Illinois and rural New England, as well as commanding majorities in their Southern stronghold, which was by now thoroughly established as the "Solid South" with unopposed or nigh-unopposed elections as the norm. All that said, however, the Republicans still fared better than they did on the presidential level - even if many of their supporters backed and campaigned for Roosevelt's presidential campaign, there were only a few cases where the Progressives were able to get any sort of coattails. Usually, this involved incumbent Republican congressmen defecting to the party, and that was quite a rare thing even for more progressive-minded ones. Most of the Republican Party on the state and local levels stayed intact through the split, and in the end the Progressives were only able to win nine seats in the House - substantially less than the 22 seats the Populists had at their peak. Their delegation would only dwindle in size from here, further contributing to the party's image as a flash in the pan that had no basis for existing outside of Roosevelt's campaign. And in spite of future attempts to break the two-party system, the Democrats and Republicans continue to dominate U.S. politics to this day.

We start this series in 1912, an interesting year for a number of reasons. Firstly because it was the last really properly three-cornered presidential race in U.S. history - in 1968, while Wallace ran a nationwide campaign with a nationwide party, he got very limited traction outside the South and even he would probably have candidly admitted that he wasn't trying to win the presidency outright, and in 1992, Perot got a reasonably impressive nationwide voteshare but won no states and wasn't really close to winning more than a handful of electoral votes. In 1912, however, there were three candidates heading nationwide organised political parties who all had significant pockets of strength around the country, although it was pretty clear from the beginning who was going to win.

The Progressive Era, which was at or near its absolute zenith in 1912, was a weird period in American political history. Generally, most American party systems consist of one "active" political party, whose formation or adoption of a new program signals the start of the party system, and a "reactive" party, who form as a broad coalition in opposition to the active party and tend to be a lot less ideologically coherent. From 1860 until about 1890, the Republicans had been the active party in American politics, formed on a platform of opposition to slavery, American nationalism and an economic policy that combined government aid for economic development (particularly rural economic development) with protectionist trade policy and strong support for big business, and gathering a coherent bloc made up of businessmen, small-town notables, farmers and Protestant churches. Opposing them were the Democrats, left over from the previous party system, and combining their old Jacksonian populist element with urban machines, Catholics and immigrants as well as the white supremacist bloc in the South, which by 1890 was completely and utterly dominant across most of the region. It was an extremely weird amalgam of interests, but through most of the period, control was maintained by a pro-business faction known as the Bourbon Democrats, who ensured that the party mostly differed from the Republicans in wanting lower tariffs and a weaker federal government. The main divide among voters had less to do with ideology and more to do with the legacy of the Civil War - if you or your family fought for the Union or otherwise identified with its cause, you probably voted Republican, and if you didn't (whether that was because you disagreed with Lincoln's conduct in office, because you were on the Confederate side, or because you came to America after 1865 and didn't have a stake in the matter), you probably voted Democratic.

By the 1890s, however, things were slipping. Grover Cleveland's presidency, usually regarded as the peak of the Bourbon Democrats, resulted in new battle lines being drawn, with a number of anti-corruption Republicans breaking with the party to support Cleveland against James G. Blaine, who was widely suspected of having sold favours to railroads during his time as Speaker of the House. On the Democratic side, meanwhile, Cleveland's conservatism drew the ire of the populist wing of the party, and after the Panic of 1893, his critics were able to take full control of the party. The 1896 DNC, dominated by southern and western anti-Bourbon interests, resulted in the nomination of William Jennings Bryan, a young firebrand from Nebraska who seemed to run against everything Cleveland stood for. The nascent People's Party, an organisation of farmers and rural workers in the West who had won a few electoral votes in 1892 and had a decent-sized bloc of seats in the House of Representatives, cross-endorsed Bryan, and the stage seemed set for a new realignment along something more like what we might recognise today as left-right lines.

Yet this never happened. Perhaps it was too early in 1896, a time when many thousands of Civil War veterans were still alive and the legacy of the conflict still shaped politics, for the political divide created by it to simply go away. Regardless, the Democrats and Republicans continued to operate, and indeed still continue to operate to this day. Bryan's crusade against the bankers and plutocrats who would "crucify mankind upon a cross of gold" did not convert the Democratic Party into a vehicle for progressive reform, and indeed conflict would continue to rage between his faction and the legacy Bourbons right up until FDR forced them together to combat the Great Depression.

Instead, the Progressive Era would come to be defined by these internecine struggles between progressive and conservative forces within each party, and it was a Republican who would implement most of the key progressive demands. In 1900, as William McKinley ran for re-election, he was persuaded to accept Governor of New York, and leading progressive Republican, Theodore Roosevelt as his running made. This was done partly as a sop to progressives within his own party, partly to neutralise Bryan's message in his second run for the presidency, and partly because the New York Republican machine wanted to neutralise Roosevelt by kicking him upstairs to a largely-powerless federal office. This backfired spectacularly the next year, when McKinley was assassinated while visiting the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, and Roosevelt assumed the presidency. He would serve for almost two full terms, winning re-election in 1904 and retiring in 1908, handing power to his hand-picked successor William Howard Taft.

Taft would go on to alienate Roosevelt and his progressive faction in office. There's been raucous historical debate over how much of a conservative Taft actually was - he continued many of Roosevelt's initiatives, and would later argue he'd gone further to break up trusts than Roosevelt had. According to this line of argument, Roosevelt moved to the left after his presidency, arguing for a "New Nationalism" which included things like social insurance, inheritance taxes, an expanded right to strike and campaign finance regulations, and while Taft continued to implement the agenda of Roosevelt's presidency, he did not support his mentor's new tack. According to Roosevelt's supporters, meanwhile, Taft had been captured by big business and was now a full-throated enemy of their movement. Wherever the truth lay - and there was probably some truth to both sides of the argument - Taft and Roosevelt became the standard-bearers for the opposing factions of the Republican Party heading into the 1912 election.

It pretty quickly became clear that the Republican state organisations mostly favoured Taft's more moderate line, and that the convention would be dominated by the conservative faction. Roosevelt's supporters blamed this on the large Southern contingent at the convention, which was both firmly conservative and hugely overrepresented relative to the number of Republican voters in those states. Disputes over this led most Roosevelt supporters to abstain on the nomination ballot, and when Taft won the nomination on the first ballot, they walked out of the convention. They hastily organised a convention for a new "Progressive Party", which nominated Roosevelt unanimously and approved a platform, the "Contract with the People", which essentially copied Roosevelt's "New Nationalist" agenda. There was one notable exception - antitrust measures, which had probably been the single most important progressive hallmark of Roosevelt's presidency, was struck from the platform in favour of vague language about "strong regulation". This was blamed on the influence of George Walbridge Perkins, one of the party's key financiers and an employee of J. P. Morgan whose progressivism included arguments for "the Good Trust", and a number of leading progressives declared the new party a lost cause before it really got going.

Nevertheless, Roosevelt was still personally popular, and a large number of rank-and-file Republicans defected to his campaign, giving him a momentum that easily overpowered Taft's official Republican campaign. Whatever Taft's personal politics might have been, the formation of the Progressive Party left the GOP firmly in conservative hands, and its campaign focused on attacking Roosevelt as a dangerous radical who would change America beyond all recognition and/or an inveterate egotist who was only running to satisfy his vanity and sabotage Taft. It wasn't a very effective strategy, and Taft, as the only status quo candidate in the race, had very few real arguments to sway voters.

But, of course, there was also a Democratic campaign. And surprisingly enough, even as the Republicans were tearing themselves apart, the Democrats appeared more united than ever. There had been a clamour for Bryan to run again - his fourth heave - but the man himself refused, believing the one thing that could hurt the party's chances at this point would be nominating a three-time loser. This meant a bitterly contested convention, a Democratic Party tradition in the making, which ended up nominating Woodrow Wilson, a southerner who moved to New Jersey to take up a professorship at Princeton University - he'd served both as president of the university and governor of the state by the time of his nomination. Wilson was known as a reformer who took an intellectual approach to politics and shared many progressive goals, but he also appealed to conservatives in the South because he came from there and remained outrageously racist even by the standards of the time. As President, even as his administration made strides on some progressive issues, the federal government was segregated, and the Southern tradition of lynchings and race riots spread throughout the United States with the apparent blessing of the White House.

Because, in case you hadn't already figured it out, the main effect of the Republican split was to give Wilson a clear run for the White House. He won 40 of 48 states and 435 electoral votes, the largest number ever recorded, despite only gaining some 41% of the popular vote. Roosevelt won another six states, mostly in the West but also including Michigan and Pennsylvania, while Taft won only Vermont and Utah.

Of course, the map I've made isn't of the presidential election - you can find good maps of that in other places already - but of the congressional election that accompanied it. By 1912, all states elected their congressmen on the same day they elected the President, except Vermont and Maine, which elected their ones alongside state elections in September. This is the origin of the saying that "as Maine goes, so goes the nation" - it wasn't that Maine's election results tended to match those across the country, it was that you could read political trends from their elections because they literally voted two months before everyone else.

1912 was the first election after the 1910 Census, and also the first after Arizona and New Mexico were admitted to the Union. The Census showed a population of 92 million, up from 76 million in 1900, and the Apportionment Act of 1911 determined that 435 seats in the House of Representatives would be adequate to represent this population. For reasons we'll no doubt get to, this is still the size of the House, even though the country has more than tripled in population since then. Anyway, this represented an increase of 44 seats from the previous election, or 41 counting the three seats given to Arizona and New Mexico in the interim, and with around 210,000 inhabitants per seat, it still represented the largest population-to-seat ratio in U.S. history up until that point. Of course, while the states were technically required to make their electoral districts compact, contiguous and equal, in practice these rules were very loosely observed in a time before the Voting Rights Act.

This would be demonstrated in more ways than one. While, again, states were required by the Apportionment Act to draw as many districts as it had representatives, the Act also allowed for representatives to be elected at-large (that is, by the entire population of the state) as needed until redistricting laws could be passed. An astonishing fourteen states did this, with Montana, Idaho and Utah electing their two-seat delegations statewide, while another eleven states used a combination of statewide and district elections. Most egregious in this regard were Oklahoma, which gained three new seats but kept using its five districts drawn in 1906, and Pennsylvania, which gained four seats but kept using its 32 previous districts. Even more astonishingly, Pennsylvania would keep doing this for ten years.

As with the presidential race, the congressional elections of 1912 were a blowout for the Democrats. Even though the House grew by 41 seats, the Republicans suffered a net loss of 28, and the Democrats won a two-thirds majority of seats. Their gains included inroads into strongly Republican regions like Pennsylvania, northern Illinois and rural New England, as well as commanding majorities in their Southern stronghold, which was by now thoroughly established as the "Solid South" with unopposed or nigh-unopposed elections as the norm. All that said, however, the Republicans still fared better than they did on the presidential level - even if many of their supporters backed and campaigned for Roosevelt's presidential campaign, there were only a few cases where the Progressives were able to get any sort of coattails. Usually, this involved incumbent Republican congressmen defecting to the party, and that was quite a rare thing even for more progressive-minded ones. Most of the Republican Party on the state and local levels stayed intact through the split, and in the end the Progressives were only able to win nine seats in the House - substantially less than the 22 seats the Populists had at their peak. Their delegation would only dwindle in size from here, further contributing to the party's image as a flash in the pan that had no basis for existing outside of Roosevelt's campaign. And in spite of future attempts to break the two-party system, the Democrats and Republicans continue to dominate U.S. politics to this day.

I wonder how much of the Progressives' failures to win as many seats given a similar amount of the Congressional vote as the Populists (~10% vs. the Populists' ~11% in 1894) could be explained by geography; the Populists' vote was concentrated in the relatively less populous West and South, while the Progressives got a lot of votes in the Northeast that didn't translate to as many seats.

Excellent work Max. I always wondered why a handful (and only a handful) of seats from elections in this era seem to have majorities not recorded.

Also I'm surprised there aren't more (any?) seats where Republicans and Progressives weren't standing down for each other to stop a Democratic win. I suppose it was the height of the fratricide.

Also I'm surprised there aren't more (any?) seats where Republicans and Progressives weren't standing down for each other to stop a Democratic win. I suppose it was the height of the fratricide.

Last edited:

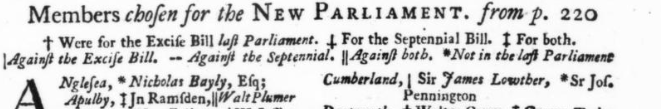

Very off topic, but I was amused to find that there is nothing new under the sun - as you may be aware, eighteenth century UK politics saw the party terms 'Whig' and 'Tory' become increasingly meaningless, not unlike the US party realignment we're discussing. And so, much like how the 1978 almanac I mentioned had to rate US congress members by their record on certain key votes, The Gentleman's Magazine did the same for the new Parliament elected in 1734.I have access to this now so I can give a bit more detail. Every senator, representative and governor (organised in the book by state not house, because America) has the following:

- Electoral career, educational background, pre-political career, religion

- Office addresses

- Committee memberships

- Group ratings. Various pressure groups rate each of them out of 100 for how in line they are with their views. We only ever seem to hear about this today with respect to guns or abortion. See below for the groups.

- Key votes, FOR, AGN or DNV. These vary from person to person but might include authorisation of the B-1 bomber, arms sales to Pinochet, splitting up the oil companies, no-fault divorce, federal funding for abortion.

- Election results

- For congressmen, a write-up about their districts at the time.

Here are the groups giving the ratings out of 100-

ADA: Americans for Democratic Action (liberal; Wiki says it faded from prominence after Nixon's victory in 1968, but it's still being quoted here in 1978)

COPE: Committee on Political Education (labour organising for political action; doesn't rate a Wiki article, had to look it up on the University of Maryland site)

PC: Public Citizen (Consumer advocacy, progressive; founded by Ralph Nader but they broke up after 2000)

RPN: Mysteriously not mentioned in the abbreviations glossary? Their numbers also usually seem to be like around 40-65 for everyone and change a lot year-on-year so I can't even tell from context what they're rating people on.

NFU: National Farmers' Union

LCV: League of Conservation Voters

CFA: Consumer Federation of America

NAB: National Association of Businessmen

NSI: National Security Index of the American Security Council

ACA: Americans for Constitutional Action (Conservatives, especially social conservatives. This is probably the most meaningful one for picking out conservative southern Democrats. Not sure how they would feel about their acronym now being applied to Obamacare...)

NTU: National Taxpayers' Union (fiscal conservatives, no you don't say, probably extremely dodgy like all pressure groups that mention paying anything in their name).

It is rather striking that there's no specific groups for guns or abortion as one is accustomed to nowadays, and a lot more focus on consumer advocacy. The book quotes the ratings on an annual basis, although not all groups made the rating that often.

I always wondered why a handful (and only a handful) of seats from elections in this era seem to have majorities not recorded.

My first source on Congressional elections (cited at bottom) has full returns all the way back to 1872. An unauthorized edit putting in the missing at-large results:

Durbin, Michael J. United States Congressional Elections, 1788-1997, The Official Results. McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina. 1998.

Excellent!My first source on Congressional elections (cited at bottom) has full returns all the way back to 1872. An unauthorized edit putting in the missing at-large results:

View attachment 72425

Durbin, Michael J. United States Congressional Elections, 1788-1997, The Official Results. McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina. 1998.

I was going to ask about Maine in, IIRC, 1920 as those results always seemed to be missing, but apparently someone has now found those as they're on Wiki now?

msmp

Insert Pine Tree Flag Here

- Pronouns

- he/him/his

Awesome work as always, Ares!

Similar dynamic at the Presidential level too, in terms of the eventual animus between the Roosevelt and Taft camps.

As for guns, you're right, but the terms of the debate were again very different. Most prominently, the cavalcade of school- and other mass-shootings that has gripped America since the Columbine era hadn't started yet. But at the same time, the NRA (today the primary pro-gun group in the US) itself was a very different beast, with expansive gun safety programs and training programs across the country; its political advocacy was restricted to maintaining the status quo, and supporting local law enforcement (that part, at least, is still a thing they do). Heck, the president of the NRA testified in favor of a sweeping gun control bill in the wake of the Kennedy (JFK and RFK) assassinations and the assassination of MLK.

And while guns were becoming a hot button issue in states with large urban centers, there wasn't a really major national movement for greater restrictions yet. The incidents that first galvanized public support for stricter regulation (beyond what had passed after the assassinations of the 1960s) were the very public killing of John Lennon in 1980, followed shortly thereafter by the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan in 1981, which was caught live on news cameras.

There was a lot of non policy-related (ie, personality) animus between the Republicans and Progressives. To the former, the Progressives were turncoats abandoning the old standard, and to the latter, the Republicans were far too cozy with the (mostly Northeastern) business and political establishment. On paper, it would have made sense for them to try to form some kind of anti-Democratic coalition, but in practical terms it just wasn't going to happen.Excellent work Max. I always wondered why a handful (and only a handful) of seats from elections in this era seem to have majorities not recorded.

Also I'm surprised there aren't more (any?) seats where Republicans and Progressives weren't standing down for each other to stop a Democratic win. I suppose it was the height of the fratricide.

Similar dynamic at the Presidential level too, in terms of the eventual animus between the Roosevelt and Taft camps.

In another reply, you mentioned the British postwar consensus; believe it or not, there was an uneasy but very real "post-Roe consensus" in American politics for most of the 1970s. Most of the anti-abortion muscle and power went into defeating the Equal Rights Amendment before turning back to the actual abortion debate in the 1980s and the run up to Planned Parenthood v. Casey (the case that first started to chip away at the broad ruling in Roe v. Wade). Likewise, the pro-choice side of the debate was focused on trying to get the ERA passed and/or convincing states to adopt their own provisions beyond or in lieu of the federal amendment. It's not until Reagan actually wins the nomination in 1980 that it becomes the kind of issue where there are groups scoring it on both sides of the partisan, and political, divide, and the emergence of the Moral Majority as a political force in the same time period.I have access to this now so I can give a bit more detail. Every senator, representative and governor (organised in the book by state not house, because America) has the following:

- Electoral career, educational background, pre-political career, religion

- Office addresses

- Committee memberships

- Group ratings. Various pressure groups rate each of them out of 100 for how in line they are with their views. We only ever seem to hear about this today with respect to guns or abortion. See below for the groups.

- Key votes, FOR, AGN or DNV. These vary from person to person but might include authorisation of the B-1 bomber, arms sales to Pinochet, splitting up the oil companies, no-fault divorce, federal funding for abortion.

- Election results

- For congressmen, a write-up about their districts at the time.

Here are the groups giving the ratings out of 100-

ADA: Americans for Democratic Action (liberal; Wiki says it faded from prominence after Nixon's victory in 1968, but it's still being quoted here in 1978)

COPE: Committee on Political Education (labour organising for political action; doesn't rate a Wiki article, had to look it up on the University of Maryland site)

PC: Public Citizen (Consumer advocacy, progressive; founded by Ralph Nader but they broke up after 2000)

RPN: Mysteriously not mentioned in the abbreviations glossary? Their numbers also usually seem to be like around 40-65 for everyone and change a lot year-on-year so I can't even tell from context what they're rating people on.

NFU: National Farmers' Union

LCV: League of Conservation Voters

CFA: Consumer Federation of America

NAB: National Association of Businessmen

NSI: National Security Index of the American Security Council

ACA: Americans for Constitutional Action (Conservatives, especially social conservatives. This is probably the most meaningful one for picking out conservative southern Democrats. Not sure how they would feel about their acronym now being applied to Obamacare...)

NTU: National Taxpayers' Union (fiscal conservatives, no you don't say, probably extremely dodgy like all pressure groups that mention paying anything in their name).

It is rather striking that there's no specific groups for guns or abortion as one is accustomed to nowadays, and a lot more focus on consumer advocacy. The book quotes the ratings on an annual basis, although not all groups made the rating that often.

As for guns, you're right, but the terms of the debate were again very different. Most prominently, the cavalcade of school- and other mass-shootings that has gripped America since the Columbine era hadn't started yet. But at the same time, the NRA (today the primary pro-gun group in the US) itself was a very different beast, with expansive gun safety programs and training programs across the country; its political advocacy was restricted to maintaining the status quo, and supporting local law enforcement (that part, at least, is still a thing they do). Heck, the president of the NRA testified in favor of a sweeping gun control bill in the wake of the Kennedy (JFK and RFK) assassinations and the assassination of MLK.

And while guns were becoming a hot button issue in states with large urban centers, there wasn't a really major national movement for greater restrictions yet. The incidents that first galvanized public support for stricter regulation (beyond what had passed after the assassinations of the 1960s) were the very public killing of John Lennon in 1980, followed shortly thereafter by the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan in 1981, which was caught live on news cameras.