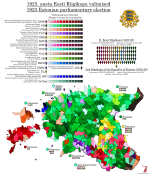

Since I already had a basemap (and a much more legibly-scaled one than the Latvian one, at that), this came together pretty quickly.

Estonia and Latvia shared some common denominators in the years immediately following independence - the two biggest parties were a social-democratic one descended from the local Mensheviks (the

Estonian Social-Democratic/Socialist (after 1925)

Workers' Party (

Eesti Sotsiaaldemokraatiline/Sotsialistlik Tööliste Partei,

ESTP)) and a right-leaning agrarian movement in which several of the most prominent leaders of the independence movement were involved (the

Farmers' Assemblies (

Põllumeeste Kogud,

PK)). However, Estonia also had a number of other significant parties, most notably the

Labour Party (

Eesti Tööerakond,

ETE), a party of the "non-Marxist left" which consciously modelled itself on the French Radical Party. Its founder, Jüri Vilms, one of the most radical independence activists, disappeared in Finland in 1918 under mysterious circumstances (he's believed to have been captured and executed by the Finnish White Guard's German allies, who did not recognise Estonian independence and saw Vilms as an obstacle to their plans to install a German-dominated government in the Baltic provinces). This did nothing to undermine the party itself, and in the 1919 Constituent Assembly election, they won 30 out of 120 seats, which alongside the 41 won by the ESTP was enough to ensure a working left-wing majority.

Which in turn ensured that the Estonian constitution came out quite different from the Latvian one, being generally a much more radical document. It declared the principle of popular sovereignty inviolable, and gave a large number of rights to the citizens including free education, free access to science and art, wide-ranging cultural autonomy for ethnic minorities, and the right to strike. The Constituent Assembly also passed a wide-ranging land reform law that was intended to break the power of the Baltic German aristocracy and ensure that rural Estonians were able to live off their land and work. In the political sphere, it followed one of the most radical interpretations of "popular sovereignty" in history, instituting a broad-ranging system of popular initiative and referendums (including to change the constitution itself) and structuring the government on an incredibly strict parliamentary basis. Although lip service was paid to Montesquieu's principles, in practice the

Riigikogu (national assembly) held nearly absolute power over all other branches of government. There wasn't even a ceremonial presidency - the head of the cabinet appointed by the

Riigikogu (styled

riigivanem, which literally translates to "state elder" or "elder of the nation",

vanem (elder) being the traditional title of a village head or small-town mayor in Estonia) was also the constitutional head of state, and could be removed at the assembly's pleasure.

The first elections to a permanent

Riigikogu, for which I unfortunately haven't found any detailed results whatsoever, were held in November 1920, a few months after Estonia signed its peace treaty with Soviet Russia and received a very favourable settlement of its eastern border. These elections saw the two governing parties take huge blows, with the ESTP in particular losing a big share of its voters either to abstention or to front organisations for the banned Communist Party. The latter were especially strong in Tallinn, where the Bolsheviks had had a significant stronghold prior to the independence struggle, and the 1920s would see radically different vote splits on the left depending on whether or not there was a significant Communist front active in any given election (very much like the situation across the water in Finland). Also complicating the picture was the

Independent Socialist Workers' Party (

Iseseisev Sotsialistlik Tööliste Partei,

ISTP), which you can basically think of as an Estonian USPD - their roots were a bit different, coming in part out of the old Estonian branch of the SRs, but they filled the same niche in the party system.

The 1920 elections also saw a good showing for the Farmers' Assemblies, who won over 20% of the vote and nearly beat the Labour Party into first place. Their leader, Konstantin Päts, now became head of state leading a coalition with Labour, the

Estonian People's Party (

Eesti Rahvaerakond,

ERE) and the

Christian Democratic Party (

Kristilik Demokraatlik Partei,

KDP). Päts had been a known figure since the 1890s, editing one of the first Estonian-language newspapers (

Teataja, which I believe means something like

The Observer or

The Gazette) and staking out a position that was at once radical in its demands for self-determination and pragmatic in the ways he went about this. He played a significant role in the independence struggle during 1918 and 1919, including leading the provisional government, while stopping short of being an Estonian Piłsudski - for one thing, his military merits were almost nonexistent, and he would always lean on his political ally General Johan Laidoner, a twenty-year Russian army veteran, to back up his words with force. Päts' most fierce rival through all this was Jaan Tõnisson, the Tartu-based editor of the rival

Postimees (

The Postman) newspaper, who had a much more academic and cultural approach to politics, criticising Päts both for being too uncompromising towards Russia (Tõnisson served in the First Duma in 1906, while Päts was driven into exile and sentenced to death in absentia for promoting treason against the Russian Empire) and for giving too much of a role to Germans and Orthodox nationalities in what was supposed to be a purely Estonian, Lutheran national project. The ERE was essentially Tõnisson's support organisation, promoting a more conservative brand of nationalism alongside a general centre-right programme, and its support was strongest by far in the Tartu region. Despite their long rivalry, Päts and Tõnisson recognised that they had a mutual interest in preventing further socialist reforms, and this was not the last time they would cooperate in government.

The Labour Party left the coalition in October 1921, but Päts carried on leading a minority government for an entire additional year until his government fell due to a corruption scandal in the newly-established national bank (Päts himself was part-owner and chairman of the Harju Bank, one of Estonia's largest private banks, and was known to reward political allies - I don't know the details of this particular scandal, but it's easy enough to imagine). This paved the way for Labour to return to power under the amazingly-named Juhan Kukk, who included the ERE and the Farmers' Assemblies in his government, and doesn't seem to have distinguished himself - he held the fort until April 1923, at which point the

Riigikogu was dissolved.

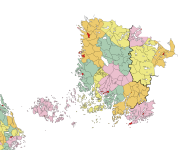

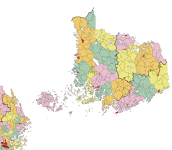

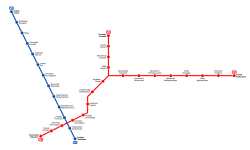

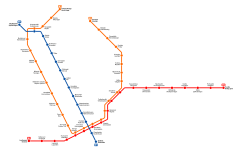

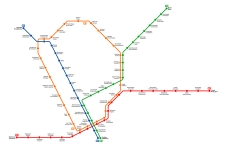

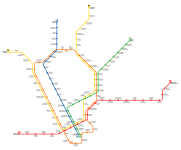

The electoral system used to elect the

Riigikogu were very similar to that of the Latvian

Saeima, with 100 seats elected proportionally in local districts according to a simple D'Hondt system. However, where Latvia grouped its districts into five large constituencies, Estonia left almost every county as a constituency unto itself, with the result that they ranged in size from 3 to 21 seats. Tallinn was separated from Harjumaa, and Valgamaa and Petserimaa, which were both small and newly-created to cover areas that had been added to Estonia since 1918, were grouped with the larger Võrumaa for electoral purposes. There were no levelling seats, but there were enough large constituencies that small parties could easily get in even without them - it was just that only voters in the larger counties would get the privilege.

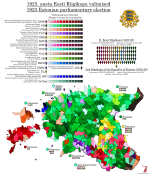

The main story of the 1923 election was the collapse of the Labour Party, whose left-wing credentials were seriously tarnished by three years in government with the likes of Päts and Tõnisson. In their place, the rural left-wing constituency went partially to the new

Settlers' Group (

Asunikkude Koondis), which would become a major player in Estonian politics as the promises of the 1919 land reform law failed to materialise, and partially to the latest Communist Party front, the

Workers' United Front (

Töörahva Ühine Väerind,

TÜV). The TÜV appear not to have been able to organise in Tallinn, because the result there was deeply weird and turnout quite low (by some sources less than 50%, compared to a national average of 67%). The ISTP began a slow collapse that would see them wiped off the political map by the next election, but nonetheless the 1923 elections presented the most fragmented result in Estonian history. The Farmers' Assemblies finally became the largest party in Estonia, but without actually gaining much in the way of votes, while the situation was complicated slightly by the arrival of a significant (well, four seats) bloc of Russian minority representatives in addition to the pre-existing German bloc.

To further complicate things, there wasn't a clear majority for the right or the left even if either side had been able to unite around a programme for government. The only option left was to return to the 1920 formula, now with the Labour element even further reduced compared to the right-wing parts of the coalition. So in August, Konstantin Päts returned as head of state for what would turn out to be far from the last time.