EDIT: Max, the other two attachments (48174 and 48175) don't seem to work, at least for me.

Hopefully they should work now - my Internet's been a bit up and down today, so it's possible something went wrong with the upload the first time around.

Anyway, I mentioned a few posts ago that Austria reminded me of British India, and that in turn reminded me that Wikipedia actually has full results (or at least full lists of members elected) for the Punjab elections of both 1937 and 1946. So here they are.

The Government of India Act 1935 made the Indian provinces fully self-governing (theoretically) for the first time. Until that point, while the provinces had had elected assemblies, those assemblies and the governments they appointed were subject to the "diarchy" system, where appointed colonial bureaucrats kept sole jurisdiction over matters such as policing and military affairs, and could veto the provincial budget. With the 1935 Act, however, the assemblies were to receive full home rule, and the idea was that this would eventually be extended to the central government, creating a "Federation of India" as a self-governing federal state within the British Empire. Kind of like Australia, except much bigger. Obviously that never happened though.

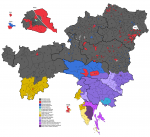

The tradition in India (and several other British colonies) was for the different religious and social communities to elect representatives on separate voter rolls, and this was carried over into the 1935 Act, which set up separate rolls for such key minority groups as Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Europeans, Anglo-Indians (i.e. biracial people, usually descended from British officials who married Indian women) and, er, women. There were also seats set aside to represent major landowners, business owners, trade unions and universities, in addition to which the Punjab had a special landowner seat for the

tumandars (chieftains) of the Baloch tribes along its western borders. With only ten (!) registered voters in 1937, this was by far the smallest constituency in the province.

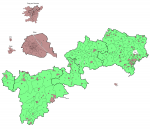

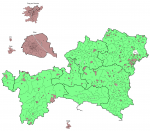

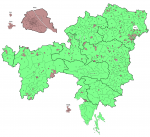

The "general" roll, which included everyone who didn't qualify for any of the other rolls, was in practice mostly Hindu, although Jains, Buddhists and Adivasi (those who could vote) were also on the general roll. When drafting the Act, the British Government had originally proposed a special roll for Scheduled Castes (i.e. the lowermost castes, mostly but not entirely synonymous with Dalits), but this was fiercely opposed by leading Dalit advocates like B. R. Ambedkar, who was able to unite the Dalit movement and the INC in opposition to this. A compromise was reached whereby certain general-roll seats would be reserved for SC candidates, who would however still be elected by the entire general-roll electorate. To make sure that areas with reserved seats didn't lose out on their non-SC representation, these were all elected in two-member constituencies. On the map, the seat with the asterisk above it is the reserved one, and the constituency is coloured by the party of its non-reserved representative.

To turn to the actual party landscape, it was pretty fragmented. Most provinces had some sort of established political parties from the diarchy period, and those mostly tried to stand for election to the new assemblies, with varying success. In the Punjab, the dominant established force was the

Unionist Party, so named not because of its pro-British position but because it sought to unify leading members of all three major religious communities. In practice, its main strength was among rural Muslims, who (just like rural people in most underdeveloped regions, then and now) voted largely based on the clientele networks led by their local imams and landowners. Their leader, Sikander Hayat Khan, was himself one of the most prominent Muslim landowners in the province, and he sat in the assembly for the North Punjab (Rawalpindi-based) landowners' constituency. He was, however, by no means a hardline traditionalist, and his government spent much of its time trying to alleviate the agricultural crisis by measures up to and including land reform. However, he refused to support the INC's plans to use the assemblies as a vehicle to agitate for independence, and when the INC-led ministries in other provinces resigned in protest against the Viceroy unilaterally declaring war on Germany in 1939, Sikander's ministry stayed in power.

The general roll in 1937 was split between the Unionists, the INC and the Hindu Election Board (of which I know absolutely nothing), while the Sikh roll was somewhat more dramatic than expected - the

Shiromani Akali Dal had always been the dominant party among the Sikh community (and to some extent still is to this day), but in 1935 it split in half, with (I think) moderate elements walking out to form the

Khalsa National Party. The KNP and the HEB, the two parties I know the absolute least about, joined the governing coalition alongside the Unionists even though the latter had a majority by themselves, and the INC and the Akali Dal became the main opposition parties.

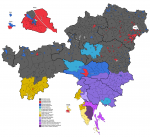

As mentioned, Sikandar's government stayed on into the war, but the man himself would not last through the end of it. In 1942, he suffered a freak heart attack and died, just fifty years old. Without their leader, the Unionists began to flag, caught between the increased demands for independence led by the INC and the rising communal consciousness of the Punjabi Muslim majority. Although he had signed the Lahore Declaration of 1940, calling for Muslim autonomy, Sikander always insisted that he was opposed to partition and the Pakistan movement, and the party largely carried on this stance after his death. This caused most of the Muslim population to desert the Unionists for the

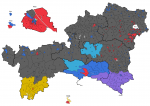

All-India Muslim League, which was quickly transforming into

the party of Indian Muslims. The Hindus, tired of war and privation, flocked to the INC, while the reunified Akali Dal was once again dominant among the Sikhs.

The January 1946 provincial elections were held very much with the expectation that India was on the cusp of independence, and the campaign focused almost entirely on what form that independence should take. The Muslim League were able to use the collapse of the Unionist machine and the rising popularity of the Pakistan movement to secure the vast majority of Muslim-roll seats, although the few Unionist holdouts coupled with a complete lack of support outside the Muslim roll (predictably) meant that they were unable to secure anywhere close to a majority overall. Instead, the INC, Akali Dal and Unionists - the anti-partition parties, broadly speaking - formed a coalition, in which the Unionists kept the premiership despite being the smallest of the three parties.

Notably, the new government had support from only a handful of Muslim seats, and none of the parties involved claimed to represent the Punjab's religious majority. This allowed the Muslim League to claim it was illegitimate, and to launch a campaign of massive resistance aimed at toppling the government from without. The province was wracked by strikes and communal violence throughout 1946, and in March 1947, the coalition government was dismissed and the Punjab came under governor's rule. The Akali Dal launched its own resistance campaign in response, leading to another bloody round of communal riots, and in June, the Viceroy Lord Mountbatten announced that partition would be going ahead on 15 August pending the approval of the provincial assemblies concerned. The INC, deeply reluctantly, endorsed the partition plan hoping for an end to the violence, but the way the British executed the plan was generally far less concerned with the lives of those involved than it was with getting the British out as quickly and cleanly as possible. On the day of partition, millions of families found themselves displaced, and with no other viable option, they made for the new international border hoping to reach safety in their community's designated homeland. This caused particular confusion in the religiously-mixed Punjab, where the border was going to leave many thousands on the "wrong" side of the border no matter how it was drawn. The mass migrations caused chaos and sparked yet another round of communal violence, this time killing hundreds of thousands of people (as you might expect, it's very hard to reach a conclusive death toll).

15 August 1947 was the death of the Punjab as a unified concept. The provincial assembly, having voted to approve partition as per the wishes of the INC and Muslim League nationally, was dissolved in July, and its members reorganised themselves into separate West and East Punjab assemblies. The former kept the old assembly buildings in Lahore, while the latter commissioned no less a figure than Le Corbusier to design a new capital city for a new Punjab State, a city that would showcase India's ambition to join the ranks of modern, free nations. Not long after this new city - Chandigarh - was completed, the state split once again.