- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

Thought these deserved a thread of their own.

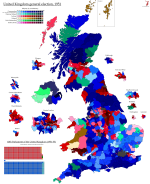

1918

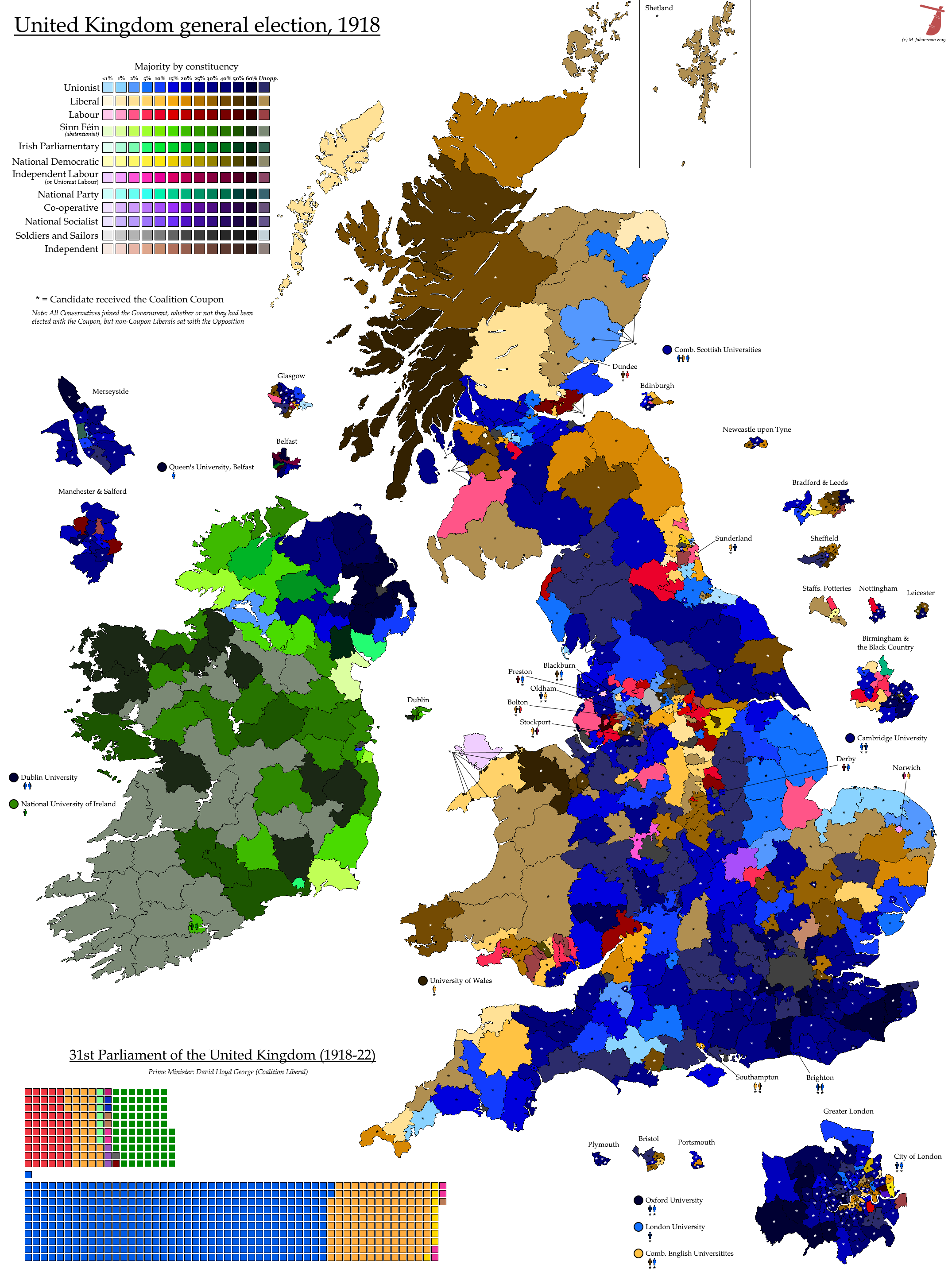

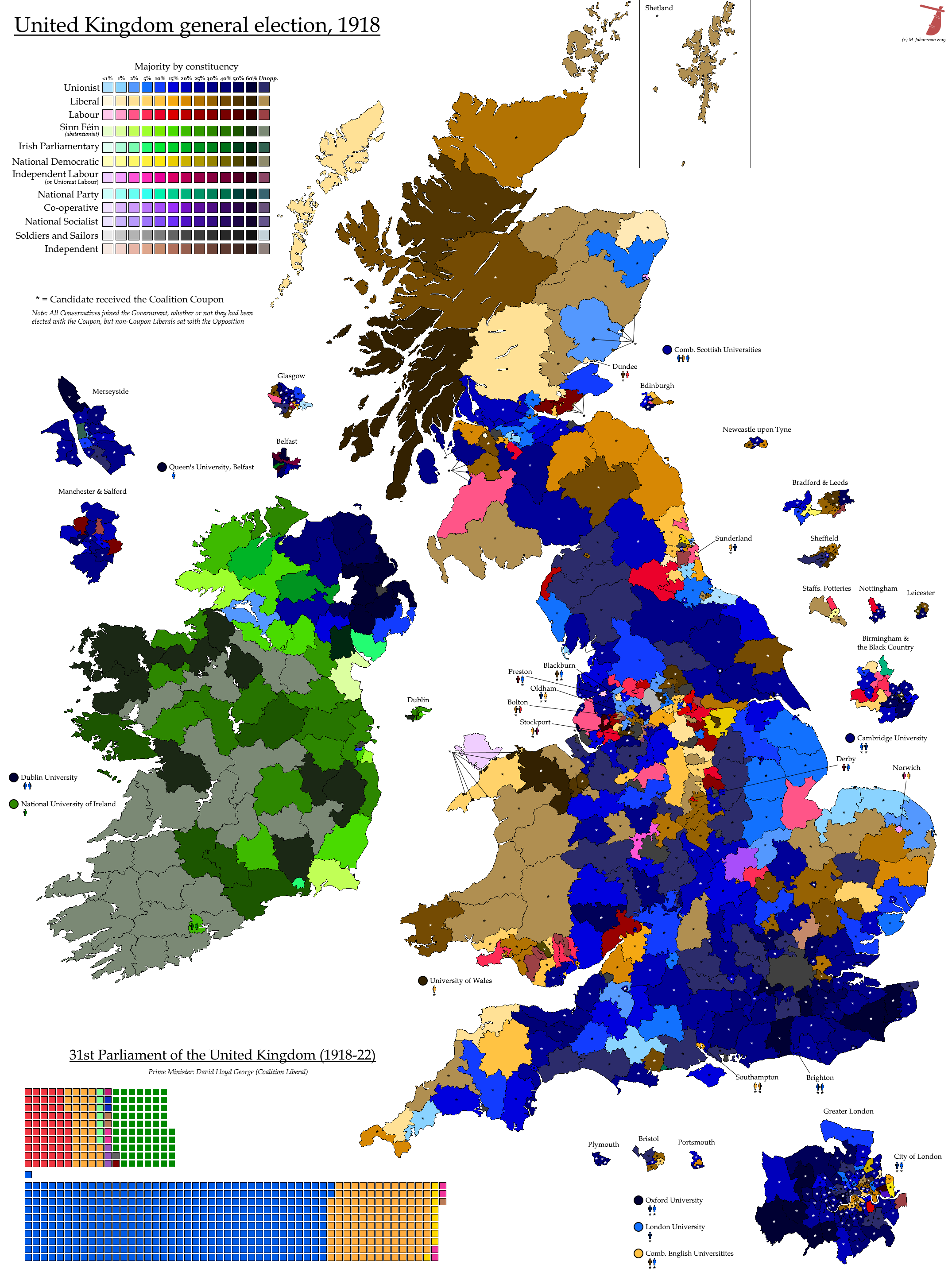

The parliament elected in December 1910 would, despite passing a bill reducing its own term from seven to five years, go on to sit for nearly eight, the longest-lived parliament since the English Civil Wars. The cause for this is obvious to us: in 1914, the First World War broke out. The parties in the House of Commons, deciding a general election would not be helpful to the war effort, formed a Coalition Government and suspended general elections until the end of the war. True to that promise, Prime Minister David Lloyd George announced the dissolution of Parliament three days after the armistice went into effect, with elections scheduled for the 14th of December, 1918.

By then, quite a lot had happened. Not merely with the war, which was too long and eventful to cover here, but in the British body politic as well. The Parliament Act had reduced the parliamentary term to five years and greatly reduced the House of Lords’ power over legislation. The Government of Ireland Act had provided for Irish home rule, although its implementation had been put on hold due to the war. And the Representation of the People Act had given the vote to all men above 21 and women above 30, the latter due to fears that the death toll from the war would put women voters in the majority.

The latter Act also provided for a massive restructuring of parliamentary constituencies, a necessary measure after thirty years of urban growth and population shifts. The House of Commons was expanded from 670 to 707 seats, the largest it had ever been or would ever be. Of course, 105 of those seats were in Ireland, where Home Rule would’ve meant a large reduction in representation if it had gone into effect.

The wartime Coalition, originally made up of members of the Unionist, Liberal and Labour parties, had shrunk significantly over its lifetime. When David Lloyd George replaced H. H. Asquith as Prime Minister in December 1916, the latter took a significant chunk of the Liberal Party with him into Opposition, and the Labour Party left at the end of the war (though a few of their members formed a new "National Democratic Party" to let them carry on supporting the Government). This left the Coalition consisting of the Unionists plus whatever Liberals backed Lloyd George over Asquith, which was usually enough to ensure a stable majority, but hardly the type of national unity that had been seen in 1914.

Lloyd George and Unionist leader Andrew Bonar Law still felt their work was unfinished, and when the election was called, they arranged for a Coupon (a form letter of endorsement signed by both leaders) to be sent to one candidate in each mainland constituency – hence the 1918 election’s common nickname, the “Coupon Election”. Unfortunately, the Coupon was private correspondence, and no unified record was made of who received it. It was up to each individual candidate to publish their Coupon and use it for their own election campaign, and some of them (mainly Liberals) disowned it while others may have simply chosen not to mention receiving it. In addition, all Unionists elected sat on the Government benches, but not all had been elected with the Coupon, so that makes it even harder to figure out how to count Coupon and non-Coupon candidates.

Whatever the exact numbers, it is however clear that the Coalition won a blowout victory. If we trust Wikipedia’s numbers, 523 out of 707 MPs elected supported the Government, with only 36 seats for Asquith’s Opposition Liberals and 57 for Labour (still their best result to date).

The biggest opposition party would be neither of these, but instead Sinn Féin, the face of radical Irish republicanism. The situation in Ireland had hardened after the 1916 Easter Rising was brutally suppressed by British force of arms and all but one of its ringleaders executed (the exception being Éamon de Valera, whose dual US citizenship made Dublin Castle fearful of causing a diplomatic incident). The decision to introduce conscription in Ireland in early 1918 did nothing to help, although a campaign led by Sinn Féin succeeded in quashing the idea before any Irishmen were conscripted. It was a tense situation by autumn 1918, and in the end, Sinn Féin were able to win 73 out of 101 Irish seats, including all but two seats outside the divided province of Ulster. The party had announced beforehand that its members would not take their seats in Westminster, instead forming a new Irish parliament out of their own number, and this was what happened. The 69 members of Dáil Éireann (the Assembly of Ireland) met in Dublin on 21 January 1919, and declared the independence of the Irish Republic.

Meanwhile in Ulster, those Protestants who had declared that they would fight any attempt to take Ireland out of the United Kingdom readied themselves for exactly such a fight, and the British Government prepared to defend the rule of law from what they saw as a treasonous rebellion. The war with Germany might be over, but peace wasn’t quite yet in sight…

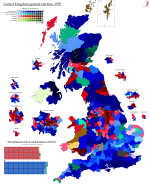

1918

The parliament elected in December 1910 would, despite passing a bill reducing its own term from seven to five years, go on to sit for nearly eight, the longest-lived parliament since the English Civil Wars. The cause for this is obvious to us: in 1914, the First World War broke out. The parties in the House of Commons, deciding a general election would not be helpful to the war effort, formed a Coalition Government and suspended general elections until the end of the war. True to that promise, Prime Minister David Lloyd George announced the dissolution of Parliament three days after the armistice went into effect, with elections scheduled for the 14th of December, 1918.

By then, quite a lot had happened. Not merely with the war, which was too long and eventful to cover here, but in the British body politic as well. The Parliament Act had reduced the parliamentary term to five years and greatly reduced the House of Lords’ power over legislation. The Government of Ireland Act had provided for Irish home rule, although its implementation had been put on hold due to the war. And the Representation of the People Act had given the vote to all men above 21 and women above 30, the latter due to fears that the death toll from the war would put women voters in the majority.

The latter Act also provided for a massive restructuring of parliamentary constituencies, a necessary measure after thirty years of urban growth and population shifts. The House of Commons was expanded from 670 to 707 seats, the largest it had ever been or would ever be. Of course, 105 of those seats were in Ireland, where Home Rule would’ve meant a large reduction in representation if it had gone into effect.

The wartime Coalition, originally made up of members of the Unionist, Liberal and Labour parties, had shrunk significantly over its lifetime. When David Lloyd George replaced H. H. Asquith as Prime Minister in December 1916, the latter took a significant chunk of the Liberal Party with him into Opposition, and the Labour Party left at the end of the war (though a few of their members formed a new "National Democratic Party" to let them carry on supporting the Government). This left the Coalition consisting of the Unionists plus whatever Liberals backed Lloyd George over Asquith, which was usually enough to ensure a stable majority, but hardly the type of national unity that had been seen in 1914.

Lloyd George and Unionist leader Andrew Bonar Law still felt their work was unfinished, and when the election was called, they arranged for a Coupon (a form letter of endorsement signed by both leaders) to be sent to one candidate in each mainland constituency – hence the 1918 election’s common nickname, the “Coupon Election”. Unfortunately, the Coupon was private correspondence, and no unified record was made of who received it. It was up to each individual candidate to publish their Coupon and use it for their own election campaign, and some of them (mainly Liberals) disowned it while others may have simply chosen not to mention receiving it. In addition, all Unionists elected sat on the Government benches, but not all had been elected with the Coupon, so that makes it even harder to figure out how to count Coupon and non-Coupon candidates.

Whatever the exact numbers, it is however clear that the Coalition won a blowout victory. If we trust Wikipedia’s numbers, 523 out of 707 MPs elected supported the Government, with only 36 seats for Asquith’s Opposition Liberals and 57 for Labour (still their best result to date).

The biggest opposition party would be neither of these, but instead Sinn Féin, the face of radical Irish republicanism. The situation in Ireland had hardened after the 1916 Easter Rising was brutally suppressed by British force of arms and all but one of its ringleaders executed (the exception being Éamon de Valera, whose dual US citizenship made Dublin Castle fearful of causing a diplomatic incident). The decision to introduce conscription in Ireland in early 1918 did nothing to help, although a campaign led by Sinn Féin succeeded in quashing the idea before any Irishmen were conscripted. It was a tense situation by autumn 1918, and in the end, Sinn Féin were able to win 73 out of 101 Irish seats, including all but two seats outside the divided province of Ulster. The party had announced beforehand that its members would not take their seats in Westminster, instead forming a new Irish parliament out of their own number, and this was what happened. The 69 members of Dáil Éireann (the Assembly of Ireland) met in Dublin on 21 January 1919, and declared the independence of the Irish Republic.

Meanwhile in Ulster, those Protestants who had declared that they would fight any attempt to take Ireland out of the United Kingdom readied themselves for exactly such a fight, and the British Government prepared to defend the rule of law from what they saw as a treasonous rebellion. The war with Germany might be over, but peace wasn’t quite yet in sight…

Last edited: