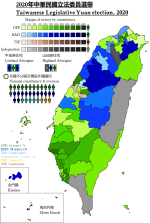

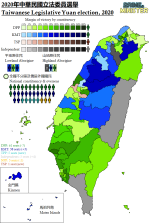

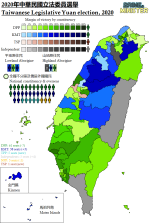

Taiwan 2020

prime-minister

Average electoral map enjoyer

- Location

- Cambridge

- Pronouns

- They/them

I've been lurking a while because I haven't had any new content I felt like posting, but I want to get started doing it so here we go! I'll mostly be posting my maps here, as well as possibly some graphics and draft ideas for stuff if people are interested in that. I might also do some reposts from my dA or from the Other Place to get them all in one place.

Anyway, I wanted to kick off with something new, and I’ve wanted for ages to do a Taiwanese map, so thanks to some very nice resources on the Chinese Wikipedia I finally got round to doing one!

Taiwan is an island between China and Japan, and that’s about all you can say about it without getting into some kind of political hot water. The de facto government of the island is known as the Republic of China, and is the descendant of the nationalist regime which governed mainland China until towards the close of the Civil War, the Communists consolidated their power and pushed the nationalist forces onto the island of Taiwan. In a frankly absurd situation, the People’s Republic of China argues that Taiwan is part of China, and Taiwan agrees, but argues that it should govern mainland China and not the PRC.

Well, sort of. That’s the argument of most of the ‘Pan-Blue’ alliance, led by the Kuomintang (KMT, Chinese: 中國國民黨, Zhōngguó Guómíndǎng), under the 1992 Consensus allegedly agreed by the PRC and ROC governments. The KMT ruled China and then Taiwan as a one-party state from the 1920s to the late 1980s, mostly because while Sun Yat-Sen really didn’t like the communist ideology of the Bolsheviks, he did like the dictatorship part (not even joking about that). After the anti-government 228 Incident, the Kuomintang brutally consolidated its rule over the island of Taiwan through the White Terror, enacting martial law and aggressively suppressing dissidents for almost 40 years.

Repealing this and turning Taiwan into a functioning democracy was a slow and complex process, largely enacted by Chiang Ching-kuo, the son of longtime KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek, during the former Chiang’s presidency from 1978 to 1988. These reforms came under pressure from the pro-democracy Tangwai (黨外) movement, which in 1986 gave rise to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, Chinese: 民主進步黨, Mínjìndǎng). The DPP's main ideological principles are liberalism and Taiwanese sovereignty, and despite spending its first six months as an illegal organisation, would ultimately manage to put significant pressure on the KMT to democratise the country, helping ensure reforms to make the Legislative Yuan and Presidency directly elected were enacted in the constitutional reform known as the Additional Articles of the Constitution.

The DPP would gradually gain strength over the course of the first decade and a bit of Taiwanese democracy thanks to fatigue with the KMT and particularly its corruption, culminating in 2000 with the victory of Chen Shui-bian in the presidential election leading to the first peaceful transfer of power in Chinese history. To support Chen, the ‘Pan-Green’ alliance was formed, comprising the DPP and allied left-leaning parties. Its emergence has led the ‘Pan-Blue’ and ‘Pan-Green’ alliances to form the backbone of Taiwanese democracy, with the KMT and DPP dominating their respective alliances but with allies holding seats of their own too.

Since 2008, Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan has had a very mixed mixed-member proportional system. It elects 113 members, 73 through single-member districts elected by FPTP, 34 through a national constituency elected by party list PR (which overseas Taiwanese also vote on) and 3 each by the lowland and highland Taiwanese Aboriginals elected by bloc vote. Just to make things more confusing, the Pan-Blue and Pan-Green alliances frequently function in the single-member districts with parties standing aside for each other or for like-minded independents, but the list PR seats are a free for all (it’s a little like Japan in that regard actually).

In 2008 it gave a massive landslide victory to the Kuomintang after the DPP and the Taiwanese electorate had soured on President Chen for his alleged corruption which they defended in 2012. However, the KMT lost much of its popularity when it supported the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA), a trade pact with the PRC, in 2014; the Sunflower Movement, as the protestors against the CSSTA became known, gained popularity by arguing the pact would put Taiwan under political pressure from Beijing, and this became a catalyst for the Taiwanese left.

Aided by this discontent, the DPP won a strong victory in the local elections, and its party chair Tsai Ing-wen managed to build up a strong lead in the run up to the 2016 presidential election, helped by the KMT being in disarray, as it was forced to withdraw its nominee Hung Hsiu-chu for the overwhelming unpopularity of her ‘one China, same interpretation’ stance. She secured the DPP’s best ever result and with this came coattails that gave the DPP a majority in the Legislative Yuan for the first time.

Tsai’s government has quite actively pursued the DPP’s agenda, cushioned by its majority in the Legislative Yuan; perhaps its most well-known policy programmes internationally have been its vocal rejection of the Chinese political system of ‘one country, two systems’ and the 1992 Consensus, opposing Chinese reunification (at least on the current terms) and advocating for liberal Taiwanese nationalism, its support for the Hong Kong protesters and making Taiwan the first country in Asia to legally recognise same-sex marriage. It has also worked to support justice for Taiwanese indigenous peoples and reduction of unemployment and wealth inequality.

After first coming back to power the DPP initially appeared to be facing setbacks, culminating in badly losing the local elections in 2018, but Tsai’s support had strengthened again by the time of the 2020 election thanks to the Hong Kong protests and she won another landslide victory. The DPP won another majority in the Legislative Yuan, but with significant losses compared to its 2016 landslide, and despite its fairly well-regarded handling of the COVID-19 pandemic the DPP again suffered losses in the 2022 local elections, as well as facing recalls against members allied with the party.

As well as two independents, the DPP-friendly parties to be elected in 2020 were the New Power Party (NPP, Chinese: 時代力量,Shídài Lìliàng), a party formed from the Sunflower Movement which acts as a more left-wing alternative to the DPP outside of its coalition a little similarly to the Korean Justice Party, and the Taiwan Statebuilding Party (TPP, Chinese: 台灣基進,Táiwān Jījìn), an independentist ally of the DPP.

The KMT’s traditional ally inside its coalition, the People First Party (PFP, Chinese: 親民黨, Qīnmín Dǎng) led by James Soong (who ran as an independent in 2000 and almost won), was shut out of the Legislative Yuan for the first time since its founding, but the centrist Taiwan People’s Party (TPP, Chinese: 民眾黨, Mínzhòngdǎng), founded by independent former Mayor of Taipei Ko Wen-je the previous year, took five list seats.

Anyway, I wanted to kick off with something new, and I’ve wanted for ages to do a Taiwanese map, so thanks to some very nice resources on the Chinese Wikipedia I finally got round to doing one!

Taiwan is an island between China and Japan, and that’s about all you can say about it without getting into some kind of political hot water. The de facto government of the island is known as the Republic of China, and is the descendant of the nationalist regime which governed mainland China until towards the close of the Civil War, the Communists consolidated their power and pushed the nationalist forces onto the island of Taiwan. In a frankly absurd situation, the People’s Republic of China argues that Taiwan is part of China, and Taiwan agrees, but argues that it should govern mainland China and not the PRC.

Well, sort of. That’s the argument of most of the ‘Pan-Blue’ alliance, led by the Kuomintang (KMT, Chinese: 中國國民黨, Zhōngguó Guómíndǎng), under the 1992 Consensus allegedly agreed by the PRC and ROC governments. The KMT ruled China and then Taiwan as a one-party state from the 1920s to the late 1980s, mostly because while Sun Yat-Sen really didn’t like the communist ideology of the Bolsheviks, he did like the dictatorship part (not even joking about that). After the anti-government 228 Incident, the Kuomintang brutally consolidated its rule over the island of Taiwan through the White Terror, enacting martial law and aggressively suppressing dissidents for almost 40 years.

Repealing this and turning Taiwan into a functioning democracy was a slow and complex process, largely enacted by Chiang Ching-kuo, the son of longtime KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek, during the former Chiang’s presidency from 1978 to 1988. These reforms came under pressure from the pro-democracy Tangwai (黨外) movement, which in 1986 gave rise to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, Chinese: 民主進步黨, Mínjìndǎng). The DPP's main ideological principles are liberalism and Taiwanese sovereignty, and despite spending its first six months as an illegal organisation, would ultimately manage to put significant pressure on the KMT to democratise the country, helping ensure reforms to make the Legislative Yuan and Presidency directly elected were enacted in the constitutional reform known as the Additional Articles of the Constitution.

The DPP would gradually gain strength over the course of the first decade and a bit of Taiwanese democracy thanks to fatigue with the KMT and particularly its corruption, culminating in 2000 with the victory of Chen Shui-bian in the presidential election leading to the first peaceful transfer of power in Chinese history. To support Chen, the ‘Pan-Green’ alliance was formed, comprising the DPP and allied left-leaning parties. Its emergence has led the ‘Pan-Blue’ and ‘Pan-Green’ alliances to form the backbone of Taiwanese democracy, with the KMT and DPP dominating their respective alliances but with allies holding seats of their own too.

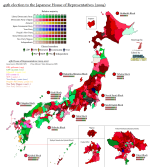

Since 2008, Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan has had a very mixed mixed-member proportional system. It elects 113 members, 73 through single-member districts elected by FPTP, 34 through a national constituency elected by party list PR (which overseas Taiwanese also vote on) and 3 each by the lowland and highland Taiwanese Aboriginals elected by bloc vote. Just to make things more confusing, the Pan-Blue and Pan-Green alliances frequently function in the single-member districts with parties standing aside for each other or for like-minded independents, but the list PR seats are a free for all (it’s a little like Japan in that regard actually).

In 2008 it gave a massive landslide victory to the Kuomintang after the DPP and the Taiwanese electorate had soured on President Chen for his alleged corruption which they defended in 2012. However, the KMT lost much of its popularity when it supported the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA), a trade pact with the PRC, in 2014; the Sunflower Movement, as the protestors against the CSSTA became known, gained popularity by arguing the pact would put Taiwan under political pressure from Beijing, and this became a catalyst for the Taiwanese left.

Aided by this discontent, the DPP won a strong victory in the local elections, and its party chair Tsai Ing-wen managed to build up a strong lead in the run up to the 2016 presidential election, helped by the KMT being in disarray, as it was forced to withdraw its nominee Hung Hsiu-chu for the overwhelming unpopularity of her ‘one China, same interpretation’ stance. She secured the DPP’s best ever result and with this came coattails that gave the DPP a majority in the Legislative Yuan for the first time.

Tsai’s government has quite actively pursued the DPP’s agenda, cushioned by its majority in the Legislative Yuan; perhaps its most well-known policy programmes internationally have been its vocal rejection of the Chinese political system of ‘one country, two systems’ and the 1992 Consensus, opposing Chinese reunification (at least on the current terms) and advocating for liberal Taiwanese nationalism, its support for the Hong Kong protesters and making Taiwan the first country in Asia to legally recognise same-sex marriage. It has also worked to support justice for Taiwanese indigenous peoples and reduction of unemployment and wealth inequality.

After first coming back to power the DPP initially appeared to be facing setbacks, culminating in badly losing the local elections in 2018, but Tsai’s support had strengthened again by the time of the 2020 election thanks to the Hong Kong protests and she won another landslide victory. The DPP won another majority in the Legislative Yuan, but with significant losses compared to its 2016 landslide, and despite its fairly well-regarded handling of the COVID-19 pandemic the DPP again suffered losses in the 2022 local elections, as well as facing recalls against members allied with the party.

As well as two independents, the DPP-friendly parties to be elected in 2020 were the New Power Party (NPP, Chinese: 時代力量,Shídài Lìliàng), a party formed from the Sunflower Movement which acts as a more left-wing alternative to the DPP outside of its coalition a little similarly to the Korean Justice Party, and the Taiwan Statebuilding Party (TPP, Chinese: 台灣基進,Táiwān Jījìn), an independentist ally of the DPP.

The KMT’s traditional ally inside its coalition, the People First Party (PFP, Chinese: 親民黨, Qīnmín Dǎng) led by James Soong (who ran as an independent in 2000 and almost won), was shut out of the Legislative Yuan for the first time since its founding, but the centrist Taiwan People’s Party (TPP, Chinese: 民眾黨, Mínzhòngdǎng), founded by independent former Mayor of Taipei Ko Wen-je the previous year, took five list seats.

Attachments

Last edited: