-

Hi Guest!

The costs of running this forum are covered by Sea Lion Press. If you'd like to help support the company and the forum, visit patreon.com/sealionpress -

Thank you to everyone who reached out with concern about the upcoming UK legislation which requires online communities to be compliant regarding illegal content. As a result of hard work and research by members of this community (chiefly iainbhx) and other members of communities UK-wide, the decision has been taken that the Sea Lion Press Forum will continue to operate. For more information, please see this thread.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Max's election maps and assorted others

- Thread starter Ares96

- Start date

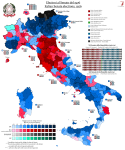

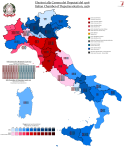

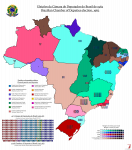

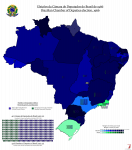

And to finish off Brazil as a theme for now, the 1962 and 1966 legislative elections:

Oh, what a change [TANKS IN THE STREETS OF THE CAPITAL, EMERGENCY INDIRECT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, MASSIVE VIOLENT REPRISALS AGAINST THE ENTIRE BROAD LEFT, AND THE BANNING OF ALL EXISTING POLITICAL PARTIES] can make.

Oh, what a change [TANKS IN THE STREETS OF THE CAPITAL, EMERGENCY INDIRECT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, MASSIVE VIOLENT REPRISALS AGAINST THE ENTIRE BROAD LEFT, AND THE BANNING OF ALL EXISTING POLITICAL PARTIES] can make.

And the NZ saga moves on.

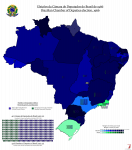

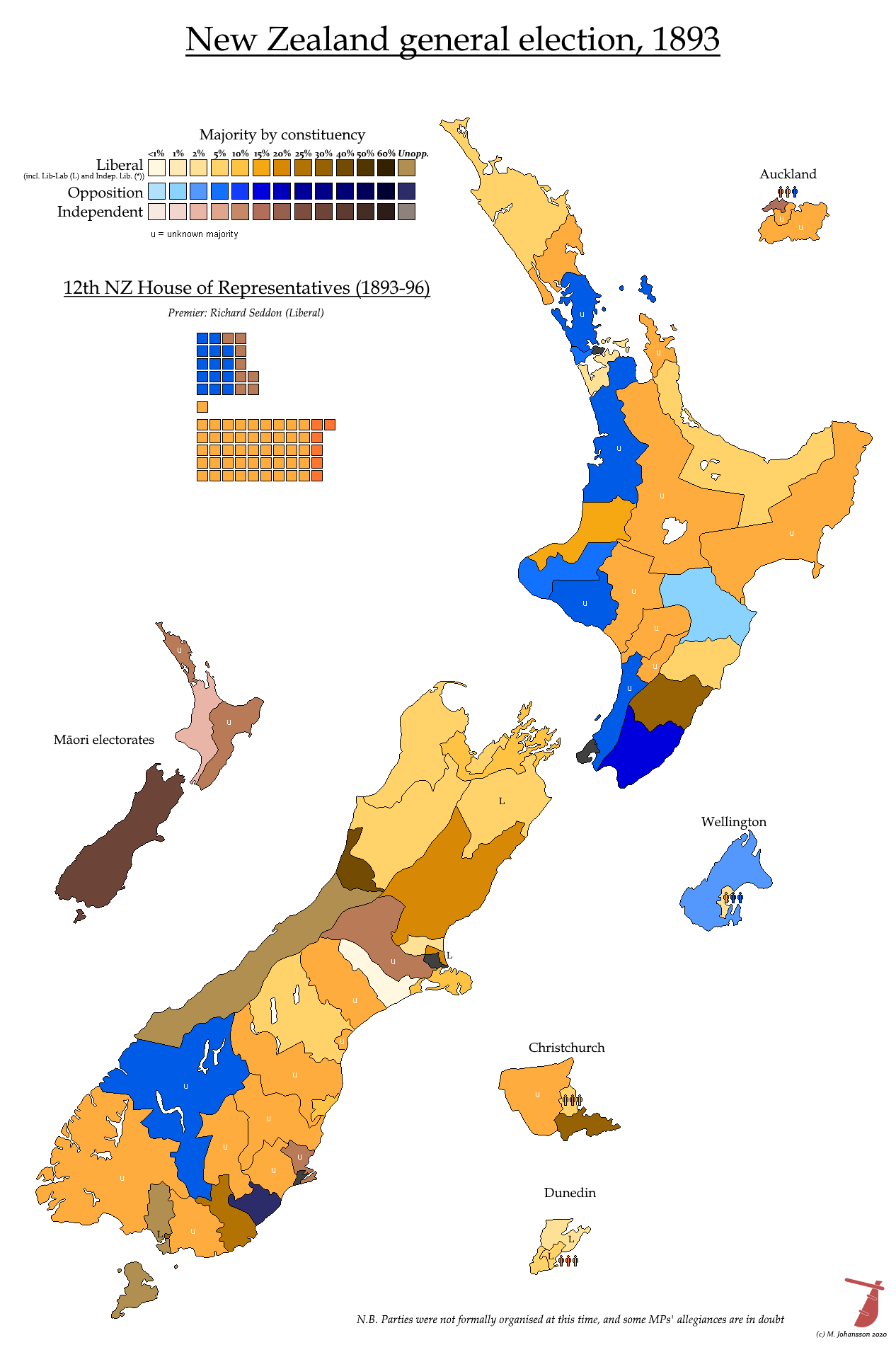

1893

The second New Zealand election featuring party competition (well - a party) saw a resounding victory for the Liberals and for the principle of party government. But the instigator of this development was not present to witness his victory, as Premier John Ballance had already been dying of bowel cancer before he was even elected to lead the Liberals. He died after 18 months in office - and because he died before having to resolve any of the inherent contradictions in the broad Liberal policy offer, he was remembered as a sort of King Arthur figure during the more divisive premierships of his successors, Seddon and Ward.

Ballance, a lower middle-class farmer's son from Ulster who had risen no further in polite society than the position of an outspoken newspaper owner-editor, had always felt inferior to the former Premier, Sir Robert Stout, who was one of the more educated and distinguished minds of the Liberal tribe - although he had the impediment of no longer being in the House. In fact, Ballance offered to resign in his favour on numerous occasions, but Stout only took his offer up when it was obvious that Ballance was a goner. The surgeons took one look at his colon and sewed him back up.

As such, when the position of Premier fell vacant, Stout (who had the support of the more educated and leftier Liberals, including Pember Reeves) was standing in a by-election, while Richard Seddon - even commoner than Ballance - was on the spot, and the latter became Acting Leader on the understanding that a ballot would be held in caucus once Stout arrived. Seddon, a wily politician even more corrupt than the general standard of the time, simply didn't hold the ballot, and became permanent leader.

Seddon was instinctively conservative: he voted against female suffrage while Stout voted in favour; he was as sceptical of Reeves' labour legislation as any rural small business owner would have been; and in the debate between leasehold and freehold, he influenced the compromise solution of the lease-in-perpetuity - a lease which was renewable every 999 years.

So, going into the 1893 election, Seddon was a Liverpudlian populist politician who was anathema to the frigid bourgeois society of New Zealand, while also being opposed to the desires of the small farmers and the urban poor who had swept the Liberals to victory three years ago - not to mention voting against the enfranchisement of the women who now constituted 50% of the electorate. How on earth did he win? Simple: as above, he was a populist.

Seddon, although he neglected the Liberal and Labour Federation and frequently overruled local Liberal groups, ran the first truly national campaign, involving stops in electorates throughout the country. Ballance had been too worried about his own electorate to do too much of this in 1890. To see Seddon giving his stump speech in your little town was the event of the season for potential Liberal voters, and his talent for playing a crowd was legendary. Most notoriously, he would always promise a new road or bridge, or some other infrastructure development, in the area. And he would do this whether or not he intended to follow through on his promises.

This was New Zealand as a colonial economy, in which the opening up of new land for more intensive settlement was literally the entire purpose of the country. The Budget surpluses that had been run under Ballance (Atkinson was a moderate deficit-spender, while the early Liberals preached balanced Budgets) would be spent on growth, while the slick new Treasurer, young Joseph Ward, would be sent to Britain to borrow huge sums to kick settlement into a higher gear.

In this manner, Richard Seddon set the scene for a long period of Liberal Government. It would not always be nice, and it would not always be as easy as it was in 1893, but the Liberal Government would continue until 1912. By the end of his life, the publican Premier would become known as 'King Dick' Seddon.

These early elections have a health warning about the party affiliation of some of the MHRs elected: there was a spectrum of people who considered themselves Liberals without being bound by the whip. These included the post-1893 Leader of the Opposition, William Russell, who was borderline radical on labour issues and considered the role of the Opposition to be to oppose the very idea of party government and the specific actions of the present government, rather than any principled opposition to their outlook. This didn't go down too well with the electorate, and after Russell resigned as Leader in 1900, the Opposition were so aimless that simply didn't elect a replacement or meet as a caucus for three years.

As such, we're going to skip the next few elections, as no rational person could find them interesting.

(Note the huge number of unknown results - the spreadsheets only start in 1905, which is easily as much of a reason for skipping ahead as me or David not being interested in the intervening elections)

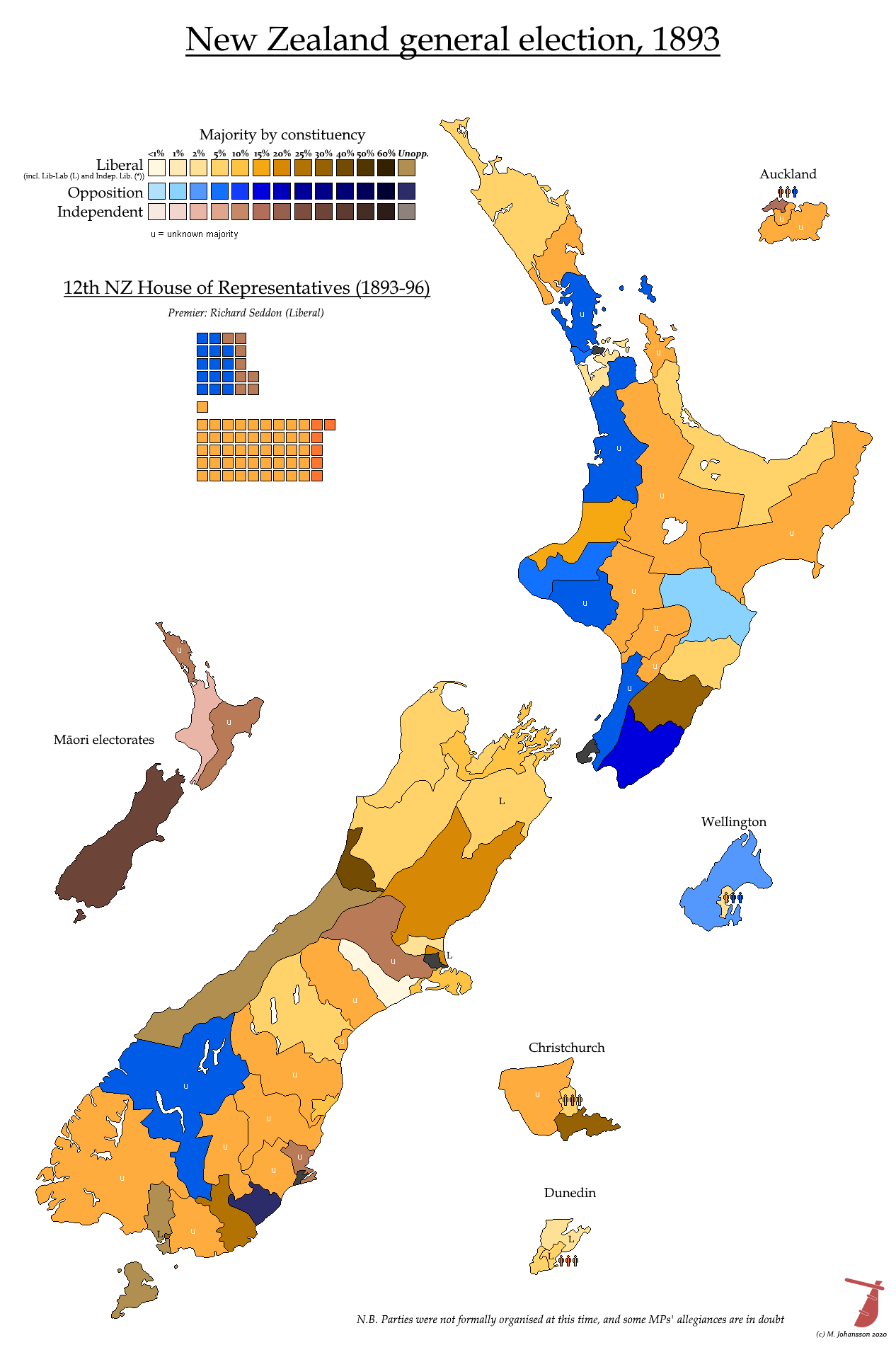

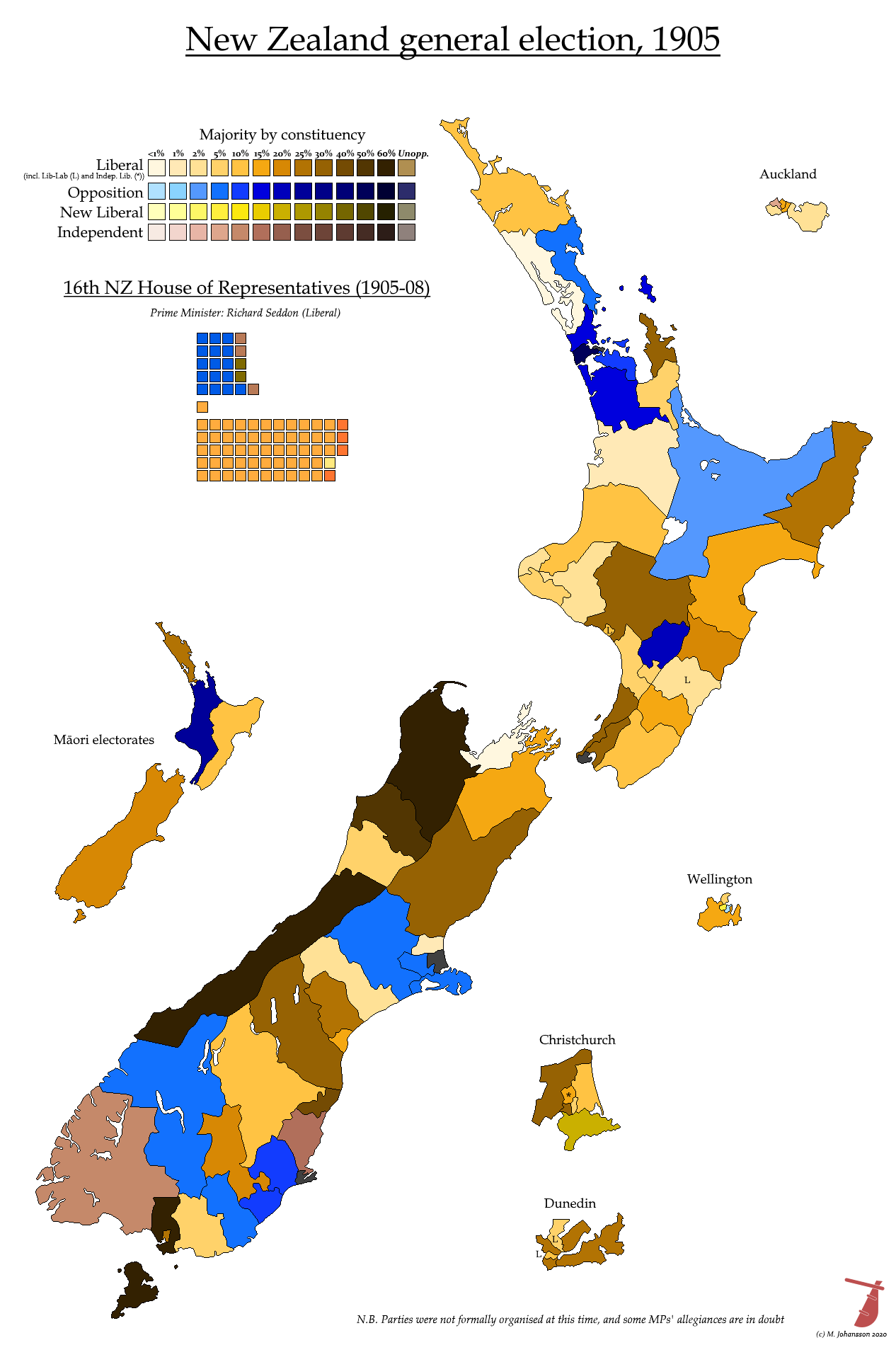

1905

Between his accession as Premier in 1892 and his final election in 1905, Richard Seddon drew the machinery of Government ever tighter around himself. It helped that New Zealand was still quite small, and that it's Government - although active in spaces that hadn't previously seen Government action anywhere in the world, such as tourism - could be done by a small and tight-knit civil service. The closeness between the civil service and the Liberal Government was underpinned by the fact that, although the permanent staff of the service were supposed to be neutral, Ministers could appoint whomever they liked to fill contracts of less than a year's duration. The result: not many permanent staff, and an ever-expanding number of people on 364-day contracts which were renewed based on whether the individual had pleased the whims of the Minister. Ministerial patronage was extended to Liberal party activists and to anyone from the Minister's electorate who wrote a suitably deferent begging-letter.

Although Seddon had a Cabinet around him, he was a workaholic, and double checked all of their paperwork himself, in addition to his half-dozen ministries. The only other person he respected at this late stage, after most of the early Liberal Ministers had died (like Jock McKenzie, the Lands Minister who had burst up precisely one big estate for closer settlement but was nevertheless universally respected) or been forced out (like Pember Reeves, who was sent to be the Government's representative in London because the House was getting bored of all his labour legislation), was the Treasurer, Joseph Ward.

Ward was one of the key players in New Zealand politics for most of his life. A smooth commercial operator, he was one of the relatively few Liberals who had experience of running a business - but he didn't let on that his business was quite speculative and that it was massively indebted to the Colonial Bank. By the mid-90s, Ward's debt had grown to immense proportions because of his position in the House of Representatives and one of the main citizens of Invercargill, meaning that the Bank simply let his overdraft grow to become a substantial proportion of their whole budget and hope for the best. And then the Colonial Bank got into tough times and had to be bought out by the Bank of New Zealand, who took one look at the Ward file and called in the bailiffs. Ward was the sort of Minister who would bluster self-pityingly about conspiracies to ruin him while quietly appointing his Colonial Bank friends to senior positions in the BNZ in the hope of a quid pro quo - or just a quid.

To cut a long story short, Joseph Ward went from a poor childhood in Melbourne to the highs of negotiating loans in London (not just for the country but secretly for himself) down to losing his seat to bankruptcy, winning the ensuing by-election, getting back into the black and rising to his former ranking in the Ministry by 1905. His story was one of rags to riches to rags to further riches, like a comic relief character in a Victorian serialised novel.

Amid this tale of Government graft and Ministerial nonentities, the Liberal backbenchers grew more and more fractious - a lot of them were realising that Seddon was never going to do a reshuffle. In addition, the radical Liberals had some concrete policy concerns, such as land nationalisation, Prohibition, and the inactivity of the Government on urban and labour concerns. And because this was the only experience New Zealand had of party government, anyone who opposed the Government was lured into the trap of opposing the whole concept. As such, when a few dissident radicals formed the New Liberal Party, they favoured an 'Elective Executive' chosen proportionally from all factions in the House.

Only a few of the rebels joined the New Liberals, and some jumped back to the official Liberals pretty quickly. The Government was frightened enough of their appeal to abolish the three-member city electorates, the last multi-member seats in the House of Representatives. However, the New Liberals latched onto accusations of corruption as their main tactic, and this backfired when Tommy Taylor accused Seddon's son of having been secretly court-martialled for cowardice in the Boer War (he had acted in the way Taylor described, but hadn't actually been court-martialled). Compounding this error, Francis Fisher accused the Government of paying Seddon's son to do work that was never done - but this accusation, which filled the column-inches for months on end, turned out to be the result of Fisher's contact confusing Captain Seddon for Captain Sneddon.

All New Liberals but Fisher and George Laurenson (later to become a Liberal Minister) were defeated and the nascent party died a death. Meanwhile, the Opposition continued to meander around the bottom of the polls despite acquiring an official Leader in the form of South Auckland dairy farmer William Massey. For now, Seddon and the Liberals were firmly on top.

I would also like to point out that 1905 saw the defeat of an MP with the incomparable name of Job Vile.

1893

The second New Zealand election featuring party competition (well - a party) saw a resounding victory for the Liberals and for the principle of party government. But the instigator of this development was not present to witness his victory, as Premier John Ballance had already been dying of bowel cancer before he was even elected to lead the Liberals. He died after 18 months in office - and because he died before having to resolve any of the inherent contradictions in the broad Liberal policy offer, he was remembered as a sort of King Arthur figure during the more divisive premierships of his successors, Seddon and Ward.

Ballance, a lower middle-class farmer's son from Ulster who had risen no further in polite society than the position of an outspoken newspaper owner-editor, had always felt inferior to the former Premier, Sir Robert Stout, who was one of the more educated and distinguished minds of the Liberal tribe - although he had the impediment of no longer being in the House. In fact, Ballance offered to resign in his favour on numerous occasions, but Stout only took his offer up when it was obvious that Ballance was a goner. The surgeons took one look at his colon and sewed him back up.

As such, when the position of Premier fell vacant, Stout (who had the support of the more educated and leftier Liberals, including Pember Reeves) was standing in a by-election, while Richard Seddon - even commoner than Ballance - was on the spot, and the latter became Acting Leader on the understanding that a ballot would be held in caucus once Stout arrived. Seddon, a wily politician even more corrupt than the general standard of the time, simply didn't hold the ballot, and became permanent leader.

Seddon was instinctively conservative: he voted against female suffrage while Stout voted in favour; he was as sceptical of Reeves' labour legislation as any rural small business owner would have been; and in the debate between leasehold and freehold, he influenced the compromise solution of the lease-in-perpetuity - a lease which was renewable every 999 years.

So, going into the 1893 election, Seddon was a Liverpudlian populist politician who was anathema to the frigid bourgeois society of New Zealand, while also being opposed to the desires of the small farmers and the urban poor who had swept the Liberals to victory three years ago - not to mention voting against the enfranchisement of the women who now constituted 50% of the electorate. How on earth did he win? Simple: as above, he was a populist.

Seddon, although he neglected the Liberal and Labour Federation and frequently overruled local Liberal groups, ran the first truly national campaign, involving stops in electorates throughout the country. Ballance had been too worried about his own electorate to do too much of this in 1890. To see Seddon giving his stump speech in your little town was the event of the season for potential Liberal voters, and his talent for playing a crowd was legendary. Most notoriously, he would always promise a new road or bridge, or some other infrastructure development, in the area. And he would do this whether or not he intended to follow through on his promises.

This was New Zealand as a colonial economy, in which the opening up of new land for more intensive settlement was literally the entire purpose of the country. The Budget surpluses that had been run under Ballance (Atkinson was a moderate deficit-spender, while the early Liberals preached balanced Budgets) would be spent on growth, while the slick new Treasurer, young Joseph Ward, would be sent to Britain to borrow huge sums to kick settlement into a higher gear.

In this manner, Richard Seddon set the scene for a long period of Liberal Government. It would not always be nice, and it would not always be as easy as it was in 1893, but the Liberal Government would continue until 1912. By the end of his life, the publican Premier would become known as 'King Dick' Seddon.

These early elections have a health warning about the party affiliation of some of the MHRs elected: there was a spectrum of people who considered themselves Liberals without being bound by the whip. These included the post-1893 Leader of the Opposition, William Russell, who was borderline radical on labour issues and considered the role of the Opposition to be to oppose the very idea of party government and the specific actions of the present government, rather than any principled opposition to their outlook. This didn't go down too well with the electorate, and after Russell resigned as Leader in 1900, the Opposition were so aimless that simply didn't elect a replacement or meet as a caucus for three years.

As such, we're going to skip the next few elections, as no rational person could find them interesting.

(Note the huge number of unknown results - the spreadsheets only start in 1905, which is easily as much of a reason for skipping ahead as me or David not being interested in the intervening elections)

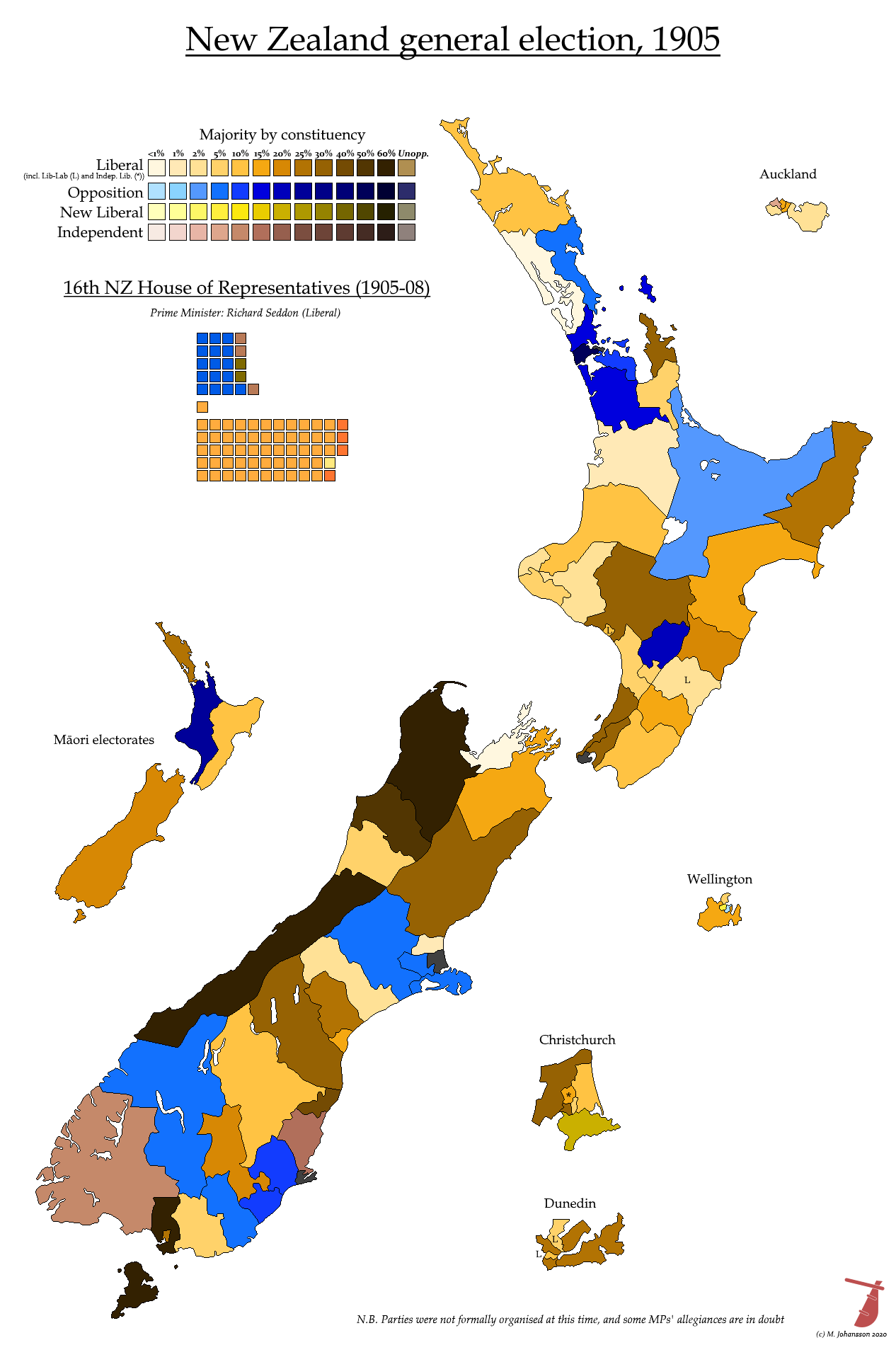

1905

Between his accession as Premier in 1892 and his final election in 1905, Richard Seddon drew the machinery of Government ever tighter around himself. It helped that New Zealand was still quite small, and that it's Government - although active in spaces that hadn't previously seen Government action anywhere in the world, such as tourism - could be done by a small and tight-knit civil service. The closeness between the civil service and the Liberal Government was underpinned by the fact that, although the permanent staff of the service were supposed to be neutral, Ministers could appoint whomever they liked to fill contracts of less than a year's duration. The result: not many permanent staff, and an ever-expanding number of people on 364-day contracts which were renewed based on whether the individual had pleased the whims of the Minister. Ministerial patronage was extended to Liberal party activists and to anyone from the Minister's electorate who wrote a suitably deferent begging-letter.

Although Seddon had a Cabinet around him, he was a workaholic, and double checked all of their paperwork himself, in addition to his half-dozen ministries. The only other person he respected at this late stage, after most of the early Liberal Ministers had died (like Jock McKenzie, the Lands Minister who had burst up precisely one big estate for closer settlement but was nevertheless universally respected) or been forced out (like Pember Reeves, who was sent to be the Government's representative in London because the House was getting bored of all his labour legislation), was the Treasurer, Joseph Ward.

Ward was one of the key players in New Zealand politics for most of his life. A smooth commercial operator, he was one of the relatively few Liberals who had experience of running a business - but he didn't let on that his business was quite speculative and that it was massively indebted to the Colonial Bank. By the mid-90s, Ward's debt had grown to immense proportions because of his position in the House of Representatives and one of the main citizens of Invercargill, meaning that the Bank simply let his overdraft grow to become a substantial proportion of their whole budget and hope for the best. And then the Colonial Bank got into tough times and had to be bought out by the Bank of New Zealand, who took one look at the Ward file and called in the bailiffs. Ward was the sort of Minister who would bluster self-pityingly about conspiracies to ruin him while quietly appointing his Colonial Bank friends to senior positions in the BNZ in the hope of a quid pro quo - or just a quid.

To cut a long story short, Joseph Ward went from a poor childhood in Melbourne to the highs of negotiating loans in London (not just for the country but secretly for himself) down to losing his seat to bankruptcy, winning the ensuing by-election, getting back into the black and rising to his former ranking in the Ministry by 1905. His story was one of rags to riches to rags to further riches, like a comic relief character in a Victorian serialised novel.

Amid this tale of Government graft and Ministerial nonentities, the Liberal backbenchers grew more and more fractious - a lot of them were realising that Seddon was never going to do a reshuffle. In addition, the radical Liberals had some concrete policy concerns, such as land nationalisation, Prohibition, and the inactivity of the Government on urban and labour concerns. And because this was the only experience New Zealand had of party government, anyone who opposed the Government was lured into the trap of opposing the whole concept. As such, when a few dissident radicals formed the New Liberal Party, they favoured an 'Elective Executive' chosen proportionally from all factions in the House.

Only a few of the rebels joined the New Liberals, and some jumped back to the official Liberals pretty quickly. The Government was frightened enough of their appeal to abolish the three-member city electorates, the last multi-member seats in the House of Representatives. However, the New Liberals latched onto accusations of corruption as their main tactic, and this backfired when Tommy Taylor accused Seddon's son of having been secretly court-martialled for cowardice in the Boer War (he had acted in the way Taylor described, but hadn't actually been court-martialled). Compounding this error, Francis Fisher accused the Government of paying Seddon's son to do work that was never done - but this accusation, which filled the column-inches for months on end, turned out to be the result of Fisher's contact confusing Captain Seddon for Captain Sneddon.

All New Liberals but Fisher and George Laurenson (later to become a Liberal Minister) were defeated and the nascent party died a death. Meanwhile, the Opposition continued to meander around the bottom of the polls despite acquiring an official Leader in the form of South Auckland dairy farmer William Massey. For now, Seddon and the Liberals were firmly on top.

I would also like to point out that 1905 saw the defeat of an MP with the incomparable name of Job Vile.

Last edited:

1908

In 1906, King Dick Seddon died on board a ship returning from Australia where he had rebuffed a final entreaty for New Zealand to join the Federation. As Joseph Ward was currently in London for an Imperial Conference, William Hall-Jones stepped in as Prime Minister in the interim - although technically in the same position as Seddon had been in during the 1892 crisis (with Ward fulfilling the Stout role), Hall-Jones only briefly thought about seizing the permanent leadership.

Joseph Ward, for all his energy, was not able to rule by force of personality in the Seddonian manner, and was a figure of fun on account of his fussy moustache and his hunger for the approval of the British upper classes (he jumped at the chance to become 'Sir Joseph' and is one of only two New Zealanders to be created a Baronet). As such, the fractious factions of the Liberal Party had to be assuaged with Ministerial positions, and Ward brought into his Cabinet such radicals as John A. Millar (the trade unionist rabble-rouser of the late 1880s), George Fowlds (a vocal Georgist single-taxer) and Alexander Hogg.

The new breadth of the Cabinet had several consequences: it was now much harder to achieve consensus in either Cabinet or caucus; Ward seemed weak for relying on people who disagreed with his previously expressed beliefs; and the backbench heroes rapidly became tarnished by office. Millar acted so repressively that he became detested by the labour movement, with fatal implications for the Liberal Government, while the previously probity-focused Hogg gained the appellation 'Minister for Roads and Bridges' within about a nanosecond.

Ward's weakness wasn't solved by the declaration of Dominion status for New Zealand in 1907 or his own apotheosis from Premier to Prime Minister. Whenever the Government tried to move in any direction it was betrayed by bold banckbench rebels, so it was no wonder that Ward fought the 1908 election on the promise of a 'legislative holiday' - a period for the reforms of the Liberal Government to bed in, and coincidentally, for the Government itself to fall prey to fewer defeats in the House.

Even those reforms which the Liberals had passed were out of touch with the new New Zealand. A prime example is the Workers' Dwellings Act, which bought up land just outside the cities, divided it up into somewhere between a large-gardened house and a small farm, and sold the parcels to urban workers as a way of solving urban unemployment and the social problems of city living. In actual fact, even if the workers and unemployed had had the funds to buy the dwellings, they would still have had to buy stock and machinery to set up the agricultural side of the operation. And even then, they could never hope to turn a profit. The theory was that they would continue to work part-time in the city and run the farmlet three or four days a week. This would have involved considerable commutes, and the workers would have had to negotiate new part-time contracts with unsympathetic employers. It's amazing that over 600 of these lots were sold under the scheme, although many of these were sold back to the state.

The Workers' Dwellings episode reflects a Government which was by now totally identified with the fiction that all urban people were simply temporarily embarrassed yeomen farmers. It was inevitable that the labour movement would begin to operate outside of the broad Liberal tent, and in 1908 the Independent Political Labour League elected its first candidate, David McLaren. Although, admittedly, the effect was marred slightly by the fact that he was only elected with Liberal support.

This situation came about due to the Second Ballot Act, which responded to the rise of Labour by instituting a two-round voting system. If no candidate won 50% of the vote on election day, a second ballot was held between the top two candidates a few weeks later - thus necessitating rural folk to travel many kilometres to their polling station and then turn and make the same journey not long after returning home. The huge Maori electorates were exempt from this, not that they had the secret ballot yet anyway.

As with many clever electoral rorts designed to salvage the governing party, the Second Ballot Act had precisely the opposite effect. Labour voters, who were definitionally annoyed with the Government, tended to move to the Opposition once excluded (thanks to Massey's efforts to wipe away the stain of Conservatism from the Opposition), while Liberals swung in behind McLaren in Wellington East and helped political Labour to embark on their mission of sweeping aside the old political spectrum.

The long decline of the Liberals was beginning.

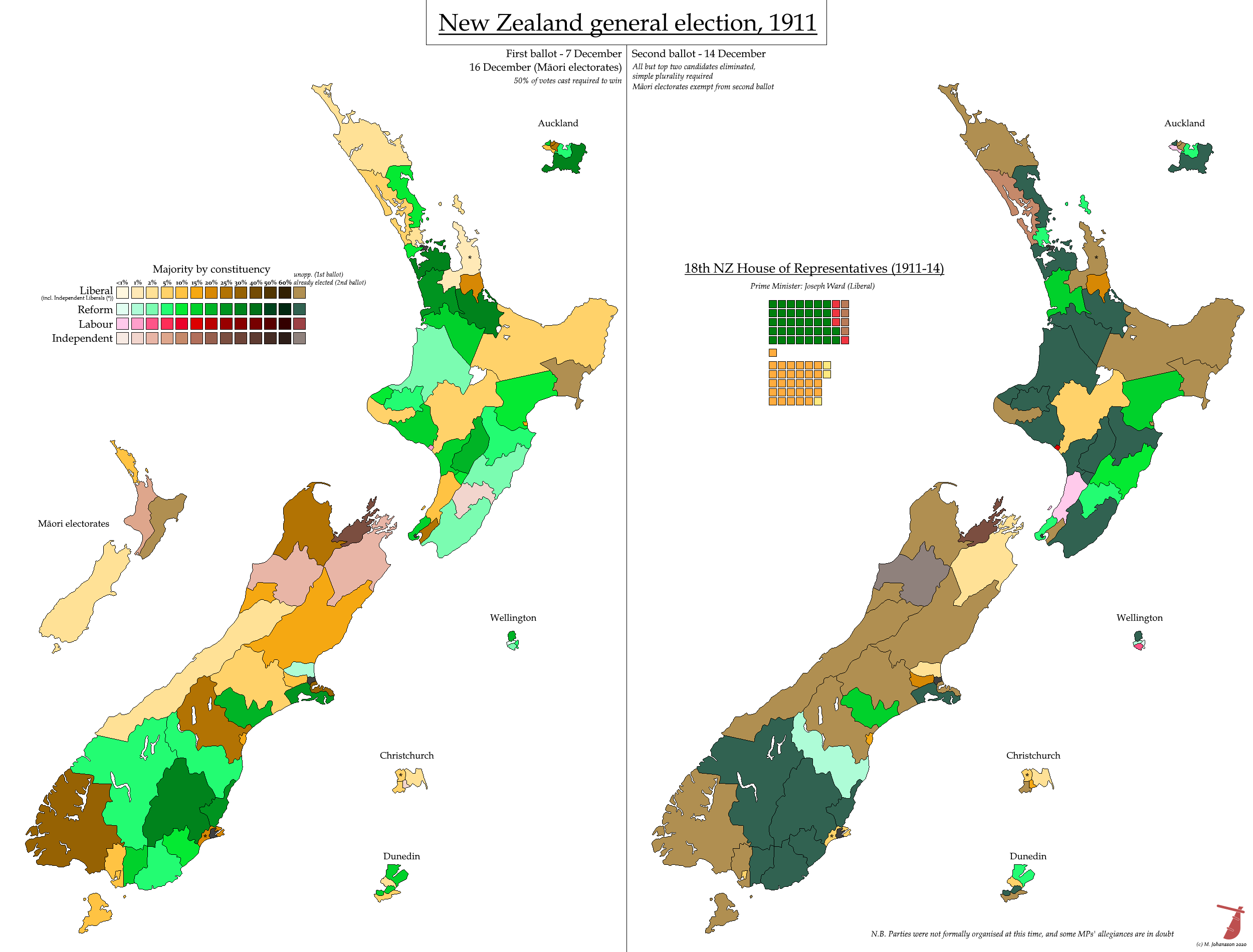

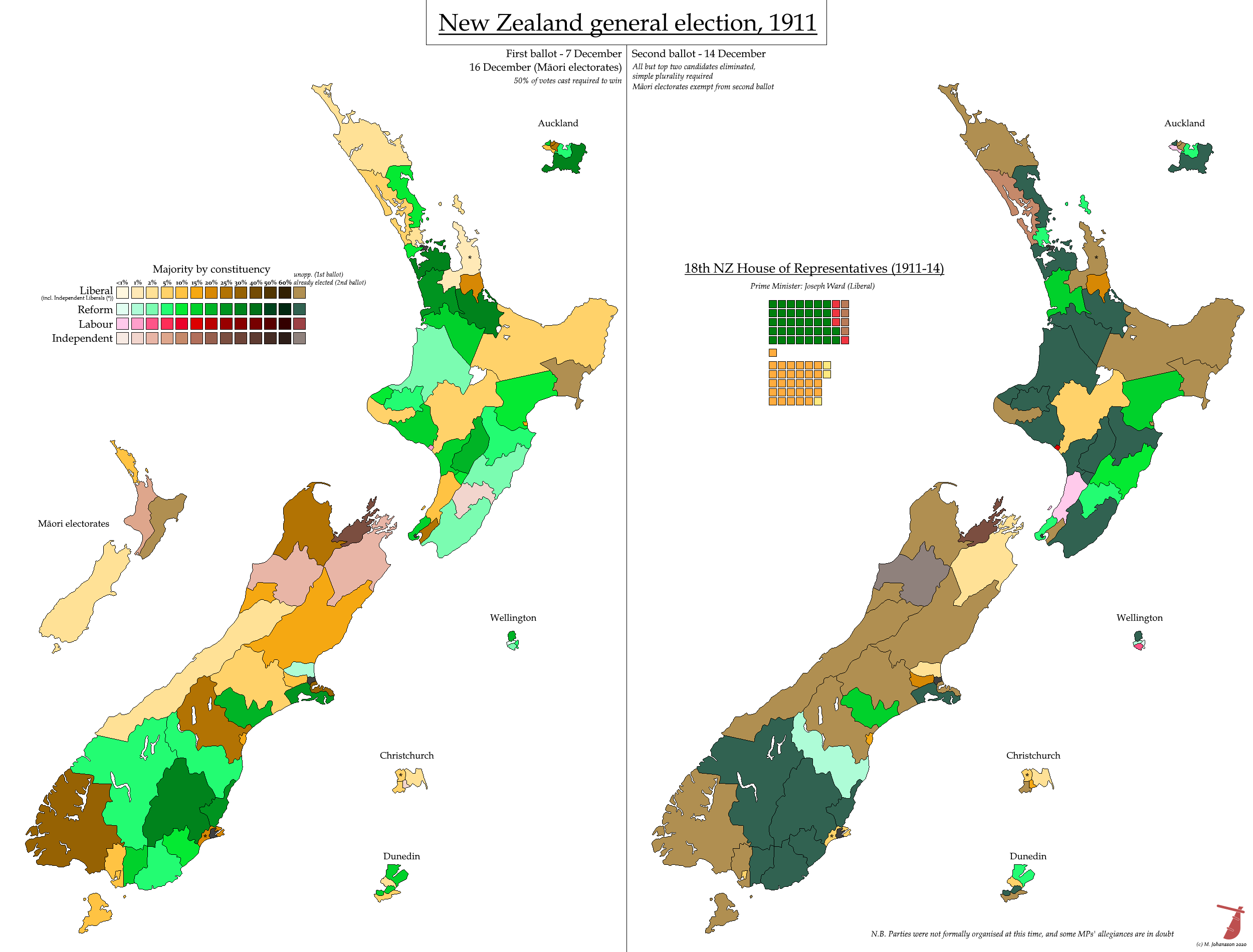

1911

You wouldn't know it to look at the voting figures, but 1911 was very much a 'change' election for New Zealand, and the aftermath was packed with melodrama. The obvious change in the run-up to the poll was the organisation of the previously diffuse Opposition into a concrete political party - which they called the Reform Party, to represent their proposals to reform the institutions, while also avoiding an obviously 'conservative' name that would still be anathema in the Dominion - even inasmuch as the Reformers were conservatives. Many of them considered themselves anti-Liberal liberals, and the rest had moderated their policies in the face of continual rejection at the polls. They now accepted party government and old-age pensions, and had even stolen the Liberals' clothes by promising to make the upper house elected by Proportional Representation.

This is not to say that Reform were simply a newer, funkier version of the Liberal Party. Their leader, Bill Massey, was a stolid and unimaginative, but dairy farmer who symbolised the Kiwi bloke - manly and practical; not given to any ideas bigger than loyalty to the Empire; resolute on the playing field but never failing to give a bluff, friendly handshake to an opponent in the Parliamentary restaurant. His worst quality was his association with odd groups like the Orange Order and the British Israelites, and his failure to repudiate the Protestant Political Association, which ran a shockingly sectarian campaign against Joseph Ward in his Awarua electorate, almost unseating the Prime Minister. To be scrupulously fair, Massey's main biographer downplays these relationships.

Even after two decades of Liberal Government, though, the Reformers couldn't win outright. The balance of power was held by an array of rural Independents (most of whom had given very specifically worded pledges to - for instance - vote for Joseph Ward on the first confidence vote of the term) and by the four Labour representatives.

Although usually described as a proper Labour caucus, only one (Alfred Hindmarsh of Wellington South) was a proper member of the official Labour Party. There was also a minor sect of hardline Socialists who mainly consisted of Australian immigrants, and an array of Independent Labourites. Bill Veitch in Wanganui was one of the latter, while John Robertson in Otaki had been endorsed by both the NZLP and by the Socialists, but considered himself to be a delegate of the Flaxmill Workers' Union. Finally, John Payne of the Auckland electorate of Grey Lynn had been opposed by official Labour, which supported the Liberal Minister of Education, George Fowlds - who had written a 'New Evangel' during the campaign to appeal to the urban worker. The New Evangel basically just reheated some old stuff about land reform, while Payne's 'Scheme 41' included some radical policies including monetary reform. Payne's team used the somewhat ludicrous name of 'People's Popular Labour'.

More to the point, the Labourites' sympathies were torn by the Second Ballot shenanigans. Hindmarsh had given his pledge to the Liberals, but both Veitch and Payne had given theirs to Massey in return for the aid of the local Reform activists against their Liberal opponents in the second round. Winning over the Labour MHRs and the rural independents was the order of the day for Ward - gambling on the efficacy of the Independents' pledges, he wrote a Speech from the Throne which seemed to have been cribbed from Payne's Scheme 41 - and the Governor struggled to keep a straight face while reading it.

There ensued a dramatic vote of confidence (in which Massey accused the Liberals of having bribed Payne to vote in their favour) in which Payne broke his pledge to the Reformers but Veitch kept his - Veitch was an honourable man and voted for Massey despite his sympathies for the Liberals, to whom he defected a few years later. In the end, the Speaker's casting vote kept the Liberals in power, but the toxic and discredited Ward resigned as Prime Minister - thus releasing the Independents from their pledges.

Those who had voted for Ward in the vote of confidence were entitled to a vote in the Liberal leadership election. The representatives of Labour, now working together in broad terms, refused to vote for fear of being seen as yet another 'Liberal-Labour' ginger group, but made the preference known. They detested John. A. Millar, who had been quite repressive against strikers as Minister of Labour, but had no such qualms about Thomas Mackenzie. Mackenzie himself was unpopular with many Liberals, as he had only relatively recently defected from the 'conservative' Opposition - so Millar and one other stormed out of the caucus in disgust when he won.

Mackenzie, like Ward before him, filled his Cabinet with radicals to counterbalance his preference for freehold tenure and his conservative reputation. Loose cannons like Harry Ell typified this short-lived Cabinet. Mackenzie was inevitably defeated in a second confidence motion - despite the unilateral support of the Labourites, the Independents turned against him (Gordon Coates, for instance, who stood as an Independent Liberal but later became a Reform Prime Minister) and so did Millar, who raised himself from his sickbed and appeared in the House in a dressing gown in order to vote against Thomas Mackenzie.

In all this drama, the Maori seats had a brief moment of relevance to the arithmetic. It is worth mentioning that the informal 'Young Maori Party', in favour of development of Maori-owned land and the repression of old-style traditions which embarrassed educated Maori in the early 20th century, split at this point. With Apirana Ngata as their standard-bearer, they had previously been behind the Liberal Party, but in 1911, Maui Pomare, a YMP candidate standing with the endorsement of the King Movement in Western Maori, kept his tinder dry and joined the Reform Party after the election, when he judged that it was valuable for the group to have a voice within the governing party. Over time, this decision sundered his ties with both Ngata and the King Movement, while undeveloped Maori land continued to be sold hand over fist to the Europeans.

For the first time in twenty-one years, an election had turfed the Government out of office - but just like last time, the incumbents had clung on with as much tenacity as they could muster, months after the writs were returned.

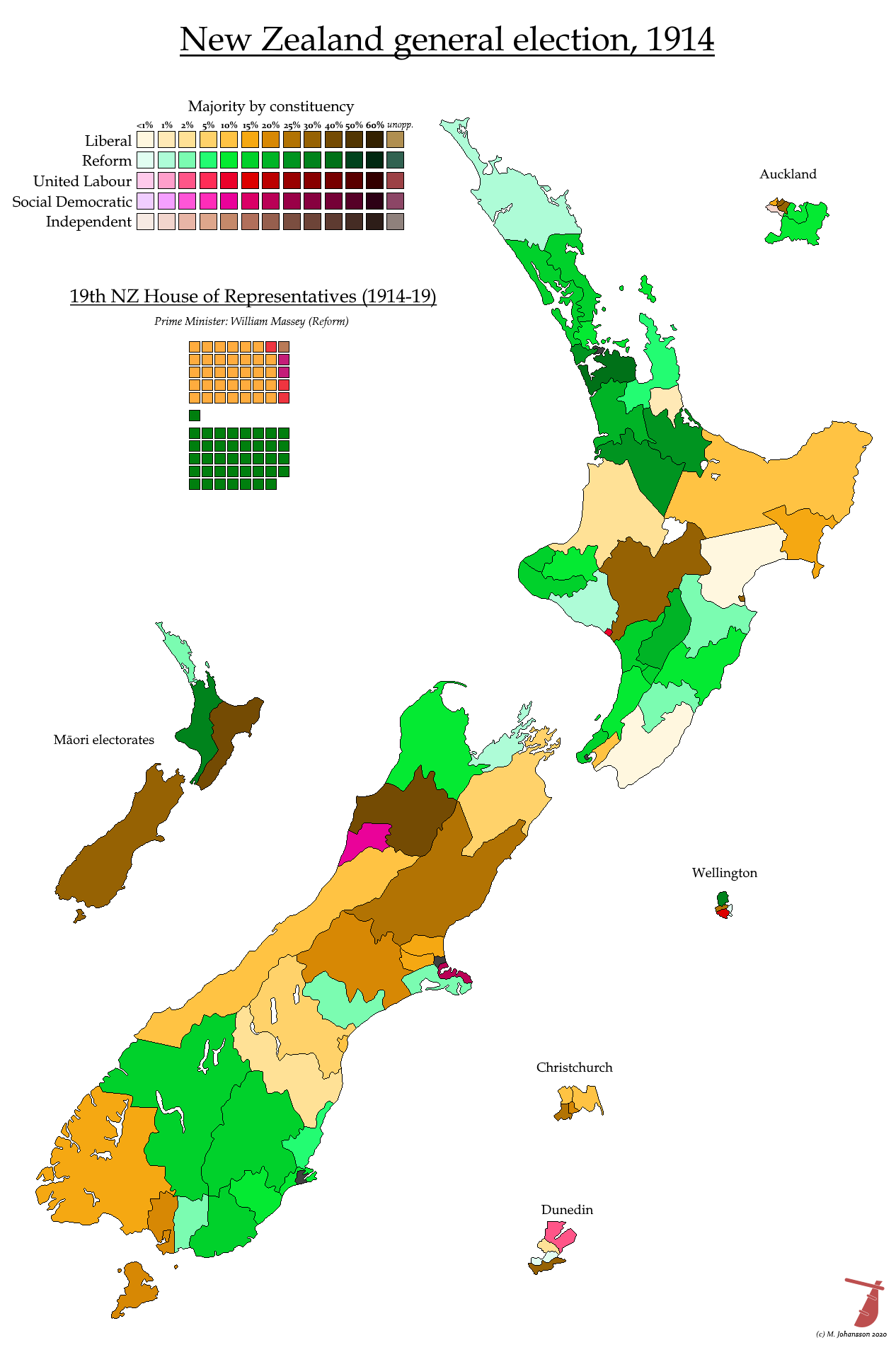

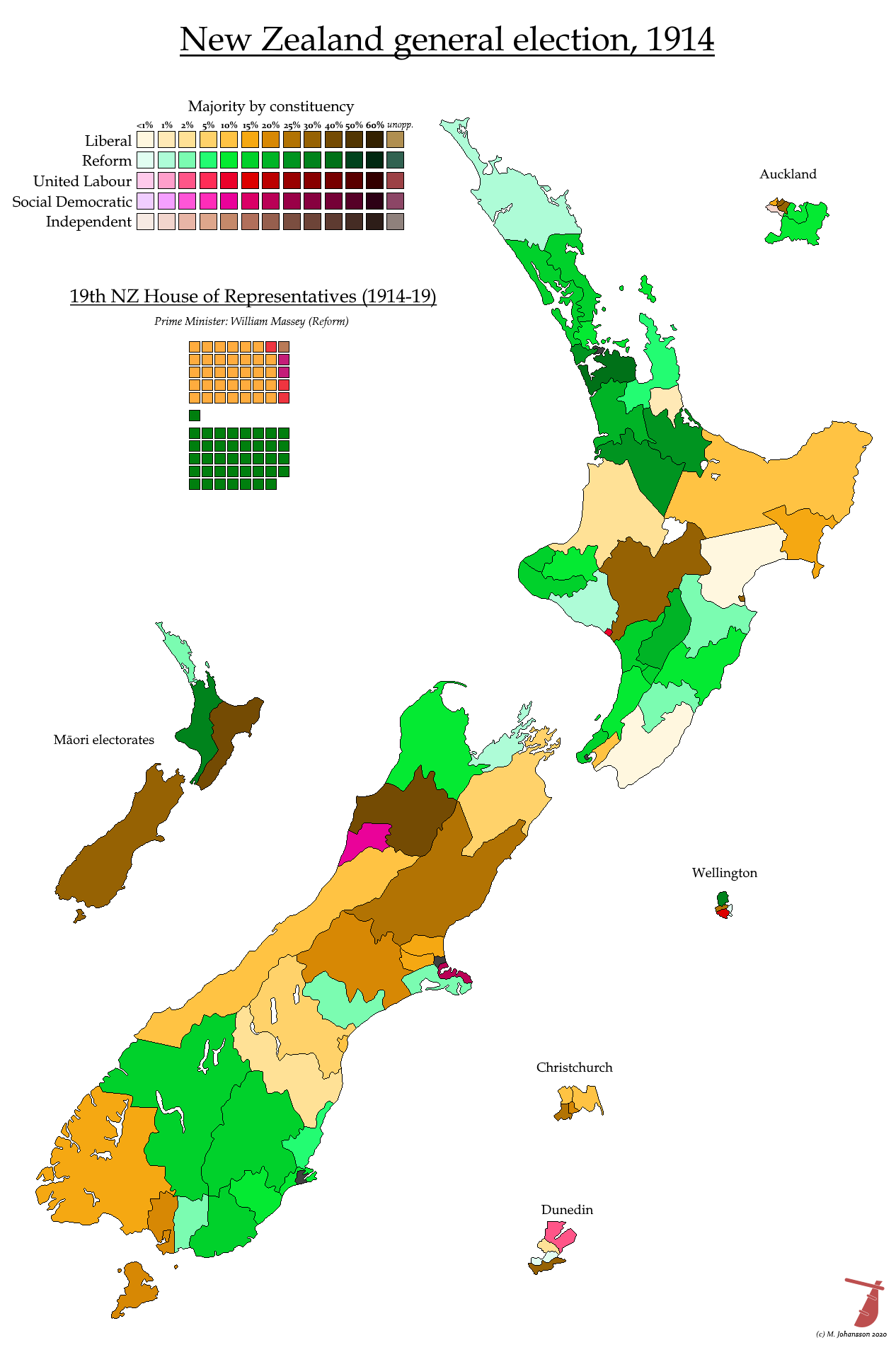

1914

The next election wasn't much more conclusive. Massey's Government, since taking over in 1912, had abolished the inconvenient Second Ballot system and reformed the Public Service to be truly independent, but in doing so had aired the old canard that Joseph Ward's appointments had been made with preference to Roman Catholics - which prompted a long defensive reply from Ward which, as usual, came across as more self-pitying than self-justifying. In other matters, Reform had extended the pensions given to widows and the aged, but the implementation of Sir Francis Dillon Bell's attempt to reform the Legislative Council, New Zealand's upper house, was repeatedly delayed for tactical reasons.

More seriously, the first term of the Reform Government had seen a shocking breakdown in New Zealand society - which the Liberals, when ascendant, had chosen to characterise as classless. Shortly after Massey took power, the radical Red Feds had encouraged a dispute in a mine at Waihi which turned nasty. Previously, the Conciliation and Arbitration system had largely prevented strikes, but the NZ Federation of Labour created a gamut of new unions independent of the official system, which theoretically had more bargaining power due to their willingness to strike - but this left the door open for employers to replace the recalcitrant workers with scabs and sign them up to a new union which would take the old union's place in the IC&A Act machinery. This was exactly what happened at Waihi, and the death of the striker Frederick George Evans in a skirmish outside the union hall lit an emotional powder-keg. Thousands flocked to his funeral in Auckland.

Shortly afterwards, the labour unrest reached Wellington as the watersiders (also affiliated to the Red Feds) joined in with a dispute supporting their comrades in Australia - the port at Wellington came to a standstill, police engaged in running battles with strikers in the streets of the city, and farmers' sons flocked down on horseback from the hills to help unload the ships and keep the colonial economy going. These young men were enrolled as special constables and became renowned for their violence towards the urban workers, whose values they didn't understand and weren't interested in learning about. The legend of 'Massey's Cossacks' was born.

The Red Feds, of course, were over-committed, and had been crushed before the election came around, but the electorate responded with a lack of confidence in the Reformers. The Minister of Marine, Francis Fisher (known as 'Rainbow' Fisher for ending up in Reform after a spell in the radical New Liberals), lost Wellington Central to the Liberals, while the two leftist parties gained seats.

Since 1911, when a solid Labour contingent had been elected for the first time, pressure had been mounting for a single Labour Party. In the first attempt, the original NZ Labour Party combined with single-tax Liberals like George Fowlds and George Laurenson to create the United Labour Party. However, this was too much in hock to the middle class Georgists (especially in Auckland) to adequately represent the movement, and a merger with the Red Fed Socialists created the Social Democratic Party in 1913. A dissident faction of the ULP, opposing the merger, won three seats while the Social Democrats won two and John Payne, Independent of both but still a Labourite, held on in Grey Lynn. They all caucused together in the House.

After all these developments, the Reform Party won precisely 40 seats out of 80 (it was thought to be 39 until Tau Henare, the new MP for Northern Maori, declared his choice of party after a suitably dramatic pause) and as the rural Independents had already been co-opted by the Reformers during the previous go-round, Massey was denied a reserve tank and was seemingly doomed to another three years of living on tenterhooks.

There was a brief hope that one of the three subsequent by-elections would change the result one way or the other. Irregularities voided the results in Taumaranui and the Bay of Islands, while the perversely principled future Speaker (and eternal rules-lawyer) Charles Statham resigned to recontest his seat because a polling clerk had made a silly mistake. After a lot of tension, all the results were unchanged and Massey grimly started to practice his counting skills.

The Bay of Islands result is interesting: the Liberal MP Vernon Reed defected to Reform before 1914, but his previous Reform opponent, George Wilkinson, insisted on standing again as an Independent Reformer. Reed tried to persuade Wilkinson to stand aside, offering to finagle him a seat in the Legislative Council and pay his election expenses - but Wilkinson wouldn't have a bar of it and Reed was barred from standing again for two years. A seat-warmer won the by-election for Reform and handed over to Reed when his ban elapsed. However, interestingly, the Liberal who almost came through the middle in 1914 was Dr. Peter Te Rangi Hiroa Buck, a distinguished Young Maori Party affiliate. If he had won, he would have been the second Maori to win a 'European' seat since his contemporary James Carroll, and the last until 1975.

In the event, Te Rangi Hiroa went to Gallipoli instead of Wellington, and the finely balanced House would transform into the biggest Government majority New Zealand has ever seen.

In 1906, King Dick Seddon died on board a ship returning from Australia where he had rebuffed a final entreaty for New Zealand to join the Federation. As Joseph Ward was currently in London for an Imperial Conference, William Hall-Jones stepped in as Prime Minister in the interim - although technically in the same position as Seddon had been in during the 1892 crisis (with Ward fulfilling the Stout role), Hall-Jones only briefly thought about seizing the permanent leadership.

Joseph Ward, for all his energy, was not able to rule by force of personality in the Seddonian manner, and was a figure of fun on account of his fussy moustache and his hunger for the approval of the British upper classes (he jumped at the chance to become 'Sir Joseph' and is one of only two New Zealanders to be created a Baronet). As such, the fractious factions of the Liberal Party had to be assuaged with Ministerial positions, and Ward brought into his Cabinet such radicals as John A. Millar (the trade unionist rabble-rouser of the late 1880s), George Fowlds (a vocal Georgist single-taxer) and Alexander Hogg.

The new breadth of the Cabinet had several consequences: it was now much harder to achieve consensus in either Cabinet or caucus; Ward seemed weak for relying on people who disagreed with his previously expressed beliefs; and the backbench heroes rapidly became tarnished by office. Millar acted so repressively that he became detested by the labour movement, with fatal implications for the Liberal Government, while the previously probity-focused Hogg gained the appellation 'Minister for Roads and Bridges' within about a nanosecond.

Ward's weakness wasn't solved by the declaration of Dominion status for New Zealand in 1907 or his own apotheosis from Premier to Prime Minister. Whenever the Government tried to move in any direction it was betrayed by bold banckbench rebels, so it was no wonder that Ward fought the 1908 election on the promise of a 'legislative holiday' - a period for the reforms of the Liberal Government to bed in, and coincidentally, for the Government itself to fall prey to fewer defeats in the House.

Even those reforms which the Liberals had passed were out of touch with the new New Zealand. A prime example is the Workers' Dwellings Act, which bought up land just outside the cities, divided it up into somewhere between a large-gardened house and a small farm, and sold the parcels to urban workers as a way of solving urban unemployment and the social problems of city living. In actual fact, even if the workers and unemployed had had the funds to buy the dwellings, they would still have had to buy stock and machinery to set up the agricultural side of the operation. And even then, they could never hope to turn a profit. The theory was that they would continue to work part-time in the city and run the farmlet three or four days a week. This would have involved considerable commutes, and the workers would have had to negotiate new part-time contracts with unsympathetic employers. It's amazing that over 600 of these lots were sold under the scheme, although many of these were sold back to the state.

The Workers' Dwellings episode reflects a Government which was by now totally identified with the fiction that all urban people were simply temporarily embarrassed yeomen farmers. It was inevitable that the labour movement would begin to operate outside of the broad Liberal tent, and in 1908 the Independent Political Labour League elected its first candidate, David McLaren. Although, admittedly, the effect was marred slightly by the fact that he was only elected with Liberal support.

This situation came about due to the Second Ballot Act, which responded to the rise of Labour by instituting a two-round voting system. If no candidate won 50% of the vote on election day, a second ballot was held between the top two candidates a few weeks later - thus necessitating rural folk to travel many kilometres to their polling station and then turn and make the same journey not long after returning home. The huge Maori electorates were exempt from this, not that they had the secret ballot yet anyway.

As with many clever electoral rorts designed to salvage the governing party, the Second Ballot Act had precisely the opposite effect. Labour voters, who were definitionally annoyed with the Government, tended to move to the Opposition once excluded (thanks to Massey's efforts to wipe away the stain of Conservatism from the Opposition), while Liberals swung in behind McLaren in Wellington East and helped political Labour to embark on their mission of sweeping aside the old political spectrum.

The long decline of the Liberals was beginning.

1911

You wouldn't know it to look at the voting figures, but 1911 was very much a 'change' election for New Zealand, and the aftermath was packed with melodrama. The obvious change in the run-up to the poll was the organisation of the previously diffuse Opposition into a concrete political party - which they called the Reform Party, to represent their proposals to reform the institutions, while also avoiding an obviously 'conservative' name that would still be anathema in the Dominion - even inasmuch as the Reformers were conservatives. Many of them considered themselves anti-Liberal liberals, and the rest had moderated their policies in the face of continual rejection at the polls. They now accepted party government and old-age pensions, and had even stolen the Liberals' clothes by promising to make the upper house elected by Proportional Representation.

This is not to say that Reform were simply a newer, funkier version of the Liberal Party. Their leader, Bill Massey, was a stolid and unimaginative, but dairy farmer who symbolised the Kiwi bloke - manly and practical; not given to any ideas bigger than loyalty to the Empire; resolute on the playing field but never failing to give a bluff, friendly handshake to an opponent in the Parliamentary restaurant. His worst quality was his association with odd groups like the Orange Order and the British Israelites, and his failure to repudiate the Protestant Political Association, which ran a shockingly sectarian campaign against Joseph Ward in his Awarua electorate, almost unseating the Prime Minister. To be scrupulously fair, Massey's main biographer downplays these relationships.

Even after two decades of Liberal Government, though, the Reformers couldn't win outright. The balance of power was held by an array of rural Independents (most of whom had given very specifically worded pledges to - for instance - vote for Joseph Ward on the first confidence vote of the term) and by the four Labour representatives.

Although usually described as a proper Labour caucus, only one (Alfred Hindmarsh of Wellington South) was a proper member of the official Labour Party. There was also a minor sect of hardline Socialists who mainly consisted of Australian immigrants, and an array of Independent Labourites. Bill Veitch in Wanganui was one of the latter, while John Robertson in Otaki had been endorsed by both the NZLP and by the Socialists, but considered himself to be a delegate of the Flaxmill Workers' Union. Finally, John Payne of the Auckland electorate of Grey Lynn had been opposed by official Labour, which supported the Liberal Minister of Education, George Fowlds - who had written a 'New Evangel' during the campaign to appeal to the urban worker. The New Evangel basically just reheated some old stuff about land reform, while Payne's 'Scheme 41' included some radical policies including monetary reform. Payne's team used the somewhat ludicrous name of 'People's Popular Labour'.

More to the point, the Labourites' sympathies were torn by the Second Ballot shenanigans. Hindmarsh had given his pledge to the Liberals, but both Veitch and Payne had given theirs to Massey in return for the aid of the local Reform activists against their Liberal opponents in the second round. Winning over the Labour MHRs and the rural independents was the order of the day for Ward - gambling on the efficacy of the Independents' pledges, he wrote a Speech from the Throne which seemed to have been cribbed from Payne's Scheme 41 - and the Governor struggled to keep a straight face while reading it.

There ensued a dramatic vote of confidence (in which Massey accused the Liberals of having bribed Payne to vote in their favour) in which Payne broke his pledge to the Reformers but Veitch kept his - Veitch was an honourable man and voted for Massey despite his sympathies for the Liberals, to whom he defected a few years later. In the end, the Speaker's casting vote kept the Liberals in power, but the toxic and discredited Ward resigned as Prime Minister - thus releasing the Independents from their pledges.

Those who had voted for Ward in the vote of confidence were entitled to a vote in the Liberal leadership election. The representatives of Labour, now working together in broad terms, refused to vote for fear of being seen as yet another 'Liberal-Labour' ginger group, but made the preference known. They detested John. A. Millar, who had been quite repressive against strikers as Minister of Labour, but had no such qualms about Thomas Mackenzie. Mackenzie himself was unpopular with many Liberals, as he had only relatively recently defected from the 'conservative' Opposition - so Millar and one other stormed out of the caucus in disgust when he won.

Mackenzie, like Ward before him, filled his Cabinet with radicals to counterbalance his preference for freehold tenure and his conservative reputation. Loose cannons like Harry Ell typified this short-lived Cabinet. Mackenzie was inevitably defeated in a second confidence motion - despite the unilateral support of the Labourites, the Independents turned against him (Gordon Coates, for instance, who stood as an Independent Liberal but later became a Reform Prime Minister) and so did Millar, who raised himself from his sickbed and appeared in the House in a dressing gown in order to vote against Thomas Mackenzie.

In all this drama, the Maori seats had a brief moment of relevance to the arithmetic. It is worth mentioning that the informal 'Young Maori Party', in favour of development of Maori-owned land and the repression of old-style traditions which embarrassed educated Maori in the early 20th century, split at this point. With Apirana Ngata as their standard-bearer, they had previously been behind the Liberal Party, but in 1911, Maui Pomare, a YMP candidate standing with the endorsement of the King Movement in Western Maori, kept his tinder dry and joined the Reform Party after the election, when he judged that it was valuable for the group to have a voice within the governing party. Over time, this decision sundered his ties with both Ngata and the King Movement, while undeveloped Maori land continued to be sold hand over fist to the Europeans.

For the first time in twenty-one years, an election had turfed the Government out of office - but just like last time, the incumbents had clung on with as much tenacity as they could muster, months after the writs were returned.

1914

The next election wasn't much more conclusive. Massey's Government, since taking over in 1912, had abolished the inconvenient Second Ballot system and reformed the Public Service to be truly independent, but in doing so had aired the old canard that Joseph Ward's appointments had been made with preference to Roman Catholics - which prompted a long defensive reply from Ward which, as usual, came across as more self-pitying than self-justifying. In other matters, Reform had extended the pensions given to widows and the aged, but the implementation of Sir Francis Dillon Bell's attempt to reform the Legislative Council, New Zealand's upper house, was repeatedly delayed for tactical reasons.

More seriously, the first term of the Reform Government had seen a shocking breakdown in New Zealand society - which the Liberals, when ascendant, had chosen to characterise as classless. Shortly after Massey took power, the radical Red Feds had encouraged a dispute in a mine at Waihi which turned nasty. Previously, the Conciliation and Arbitration system had largely prevented strikes, but the NZ Federation of Labour created a gamut of new unions independent of the official system, which theoretically had more bargaining power due to their willingness to strike - but this left the door open for employers to replace the recalcitrant workers with scabs and sign them up to a new union which would take the old union's place in the IC&A Act machinery. This was exactly what happened at Waihi, and the death of the striker Frederick George Evans in a skirmish outside the union hall lit an emotional powder-keg. Thousands flocked to his funeral in Auckland.

Shortly afterwards, the labour unrest reached Wellington as the watersiders (also affiliated to the Red Feds) joined in with a dispute supporting their comrades in Australia - the port at Wellington came to a standstill, police engaged in running battles with strikers in the streets of the city, and farmers' sons flocked down on horseback from the hills to help unload the ships and keep the colonial economy going. These young men were enrolled as special constables and became renowned for their violence towards the urban workers, whose values they didn't understand and weren't interested in learning about. The legend of 'Massey's Cossacks' was born.

The Red Feds, of course, were over-committed, and had been crushed before the election came around, but the electorate responded with a lack of confidence in the Reformers. The Minister of Marine, Francis Fisher (known as 'Rainbow' Fisher for ending up in Reform after a spell in the radical New Liberals), lost Wellington Central to the Liberals, while the two leftist parties gained seats.

Since 1911, when a solid Labour contingent had been elected for the first time, pressure had been mounting for a single Labour Party. In the first attempt, the original NZ Labour Party combined with single-tax Liberals like George Fowlds and George Laurenson to create the United Labour Party. However, this was too much in hock to the middle class Georgists (especially in Auckland) to adequately represent the movement, and a merger with the Red Fed Socialists created the Social Democratic Party in 1913. A dissident faction of the ULP, opposing the merger, won three seats while the Social Democrats won two and John Payne, Independent of both but still a Labourite, held on in Grey Lynn. They all caucused together in the House.

After all these developments, the Reform Party won precisely 40 seats out of 80 (it was thought to be 39 until Tau Henare, the new MP for Northern Maori, declared his choice of party after a suitably dramatic pause) and as the rural Independents had already been co-opted by the Reformers during the previous go-round, Massey was denied a reserve tank and was seemingly doomed to another three years of living on tenterhooks.

There was a brief hope that one of the three subsequent by-elections would change the result one way or the other. Irregularities voided the results in Taumaranui and the Bay of Islands, while the perversely principled future Speaker (and eternal rules-lawyer) Charles Statham resigned to recontest his seat because a polling clerk had made a silly mistake. After a lot of tension, all the results were unchanged and Massey grimly started to practice his counting skills.

The Bay of Islands result is interesting: the Liberal MP Vernon Reed defected to Reform before 1914, but his previous Reform opponent, George Wilkinson, insisted on standing again as an Independent Reformer. Reed tried to persuade Wilkinson to stand aside, offering to finagle him a seat in the Legislative Council and pay his election expenses - but Wilkinson wouldn't have a bar of it and Reed was barred from standing again for two years. A seat-warmer won the by-election for Reform and handed over to Reed when his ban elapsed. However, interestingly, the Liberal who almost came through the middle in 1914 was Dr. Peter Te Rangi Hiroa Buck, a distinguished Young Maori Party affiliate. If he had won, he would have been the second Maori to win a 'European' seat since his contemporary James Carroll, and the last until 1975.

In the event, Te Rangi Hiroa went to Gallipoli instead of Wellington, and the finely balanced House would transform into the biggest Government majority New Zealand has ever seen.

Last edited:

More NZ maps. Writeups once again courtesy of @Uhura's Mazda.

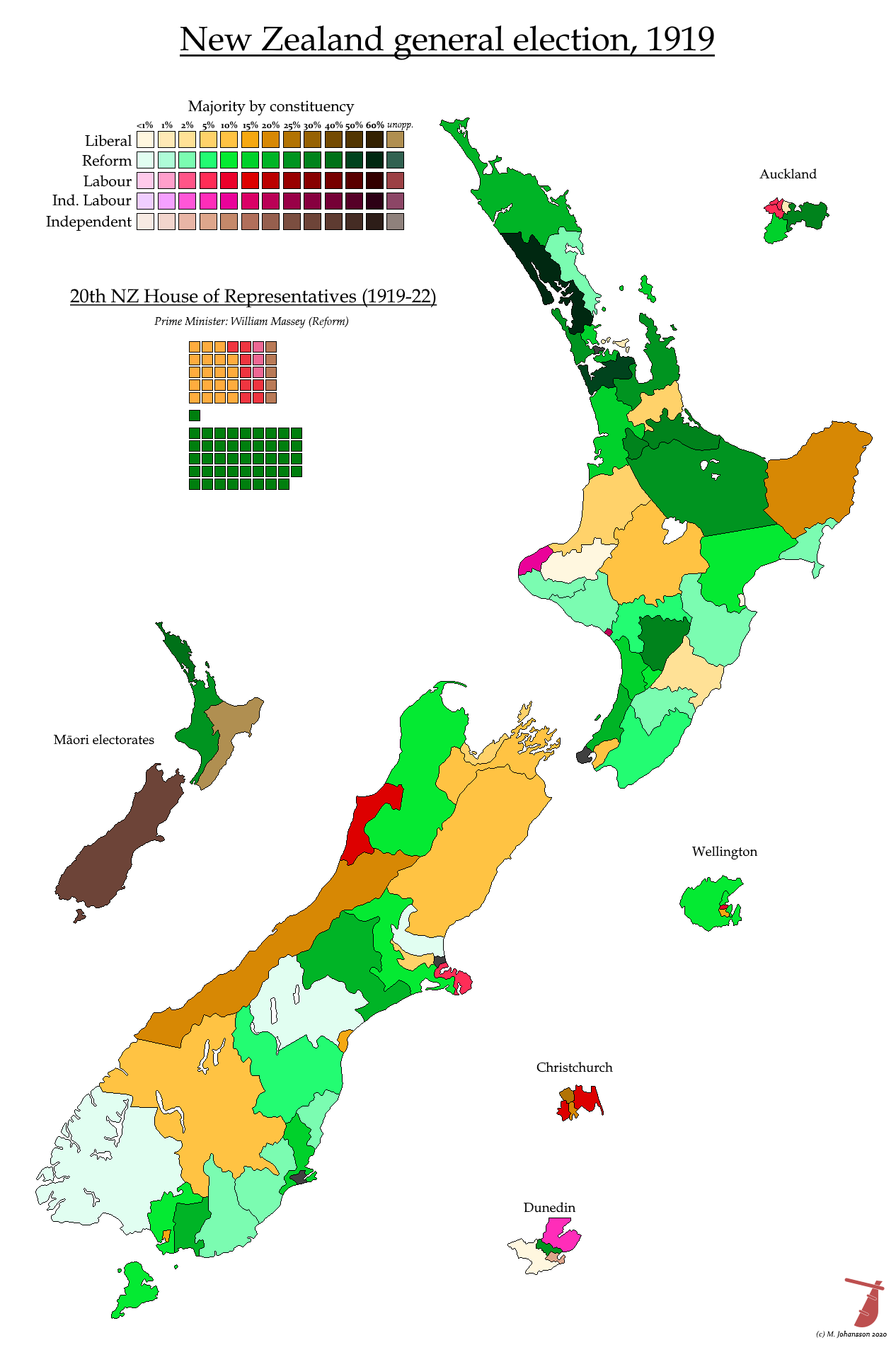

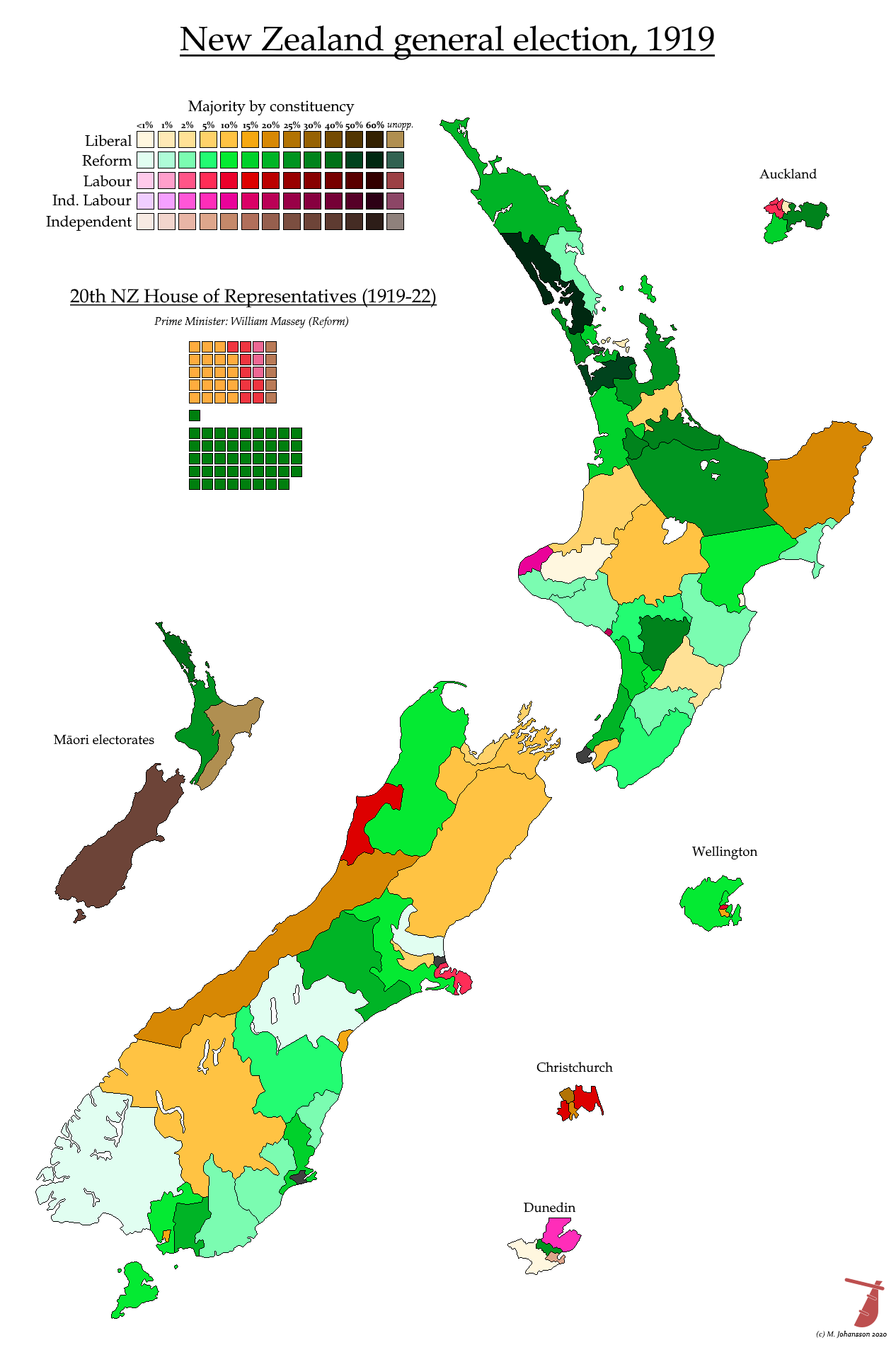

1919

The election scheduled for 1917 was delayed by two years due to the First World War - a crisis which tested the bluff dairy farmer Bill Massey beyond his expectations. He came through largely with flying colours, being respected at Imperial Conferences and loved by the troops on the front line, whom he made a point of visiting. In these overseas jaunts, he was joined by his Deputy, none other than Sir Joseph Ward. Ward (Liberal leader once more) joined in the wartime coalition government in 1915 and insisted on being treated as an equal to Massey wherever they went - much to the exasperation of other delegates to Conferences, who wanted small and effective meetings. Ward had a tendency to intervene late in the debate and make a long, rambling speech which largely went over ground already covered and which added virtually nothing, while the other Dominion representatives seethed and surreptitiously consulted their watches.

At the same time as the Reformers and Liberals temporarily put aside their differences, the Labour movement followed the same course on a more permanent basis. The existing Social Democratic and United Labour Parties united in 1916, forming the current Labour Party, and went on to encouraging successes in by-elections and in the 1919 general election, when they leaped up from a combined 8% of the vote to 24%, and 8 seats. Not all of the movement joined the Party, though: the idiosyncratic John Payne remained outside the tent due to his support for conscription and was defeated by the NZLP, while Bill Veitch of Wanganui went Independent due to his fundamental distaste for supporting strikers. Another pro-conscription Independent Labour candidate, Edward Kellett, unseated the Labour MHR for Dunedin North, while Sid Smith, elected as Independent Labour for New Plymouth, drifted to the Liberals shortly afterwards.

The Labour Party had been vocal and resolute in opposing conscription and calling for the conscription of wealth, to the extent that some of their leading figures were imprisoned for sedition. This included Peter Fraser (who was familiar with gaol due to his imprisonment over the 1913 Red Fed strike in Wellington), a future Prime Minister who - ironically - not only imposed conscription during the Second World War but staked his leadership on continuing it in peacetime. More significantly, the radical representative for the South Island mining seat of Grey, Paddy Webb, was imprisoned briefly for sedition and, after his release, refused to comply with his call-up papers. Seeking a mandate for his stand, he resigned and precipitated a by-election, in which he was returned unopposed as the Government refused to dignify it with a contest. Webb was sentenced to two years planting trees and a decade-long ban on holding public office, so at a second by-election Harry Holland - the Australian-born hardliner, soon to become a long-serving Labour Leader - entered Parliament.

While Labour united, the Reform Party almost split asunder. The necessity during the wartime coalition of finding places for Liberals in the Cabinet meant that ambitious Reformers would inevitably miss out. In early 1919 a group of these disgruntled backbenchers grouped together and began to talk about forming a Progressive Party - their platform was quite radical, proposing state control of agricultural export marketing, generous pensions and a state-owned shipping company. The last of these wasn't established until the Labour Government of the 1970s. The Progressives even began to scout out for a charismatic leader, landing on an Army General who had been at Gallipolli. However, events moved quicker than expected: Ward pulled the Liberals out of the Government and issued a manifesto closely based on the Progressive one, and Massey responded by appointing a couple of the rebels to vacant spaces in Cabinet. One of the ringleaders was frozen out of the Reform Party and the rest balked at explaining to the electorate why they had not simply joined the Liberals.

The Progressive incident was based in part upon the discontent that rural primary producers felt as a result of the post-war Depression, and it is no accident that the same period saw the emergence of the Progressive Party in Canada and the Country Party in Australia.

Another major change was that women now had the right to stand in parliamentary elections (they had gained the right to vote in advance of the 1893 poll, second only to Wyoming). Each of the three parties stood a single woman, but none were elected - and the first woman MP came only in 1933.

With the Liberals abandoning the centre ground and Labour splitting the vote on the left, Massey won a genuine majority for the first and only time during his two-decade spell in leadership. Even so, he won just 35% of the vote. But the Liberals unarguably had the worst of it: they fell to 19 seats and suffered the ignominy of losing their Leader, Sir Joseph Ward. His role would be filled by lesser men in the years to come.

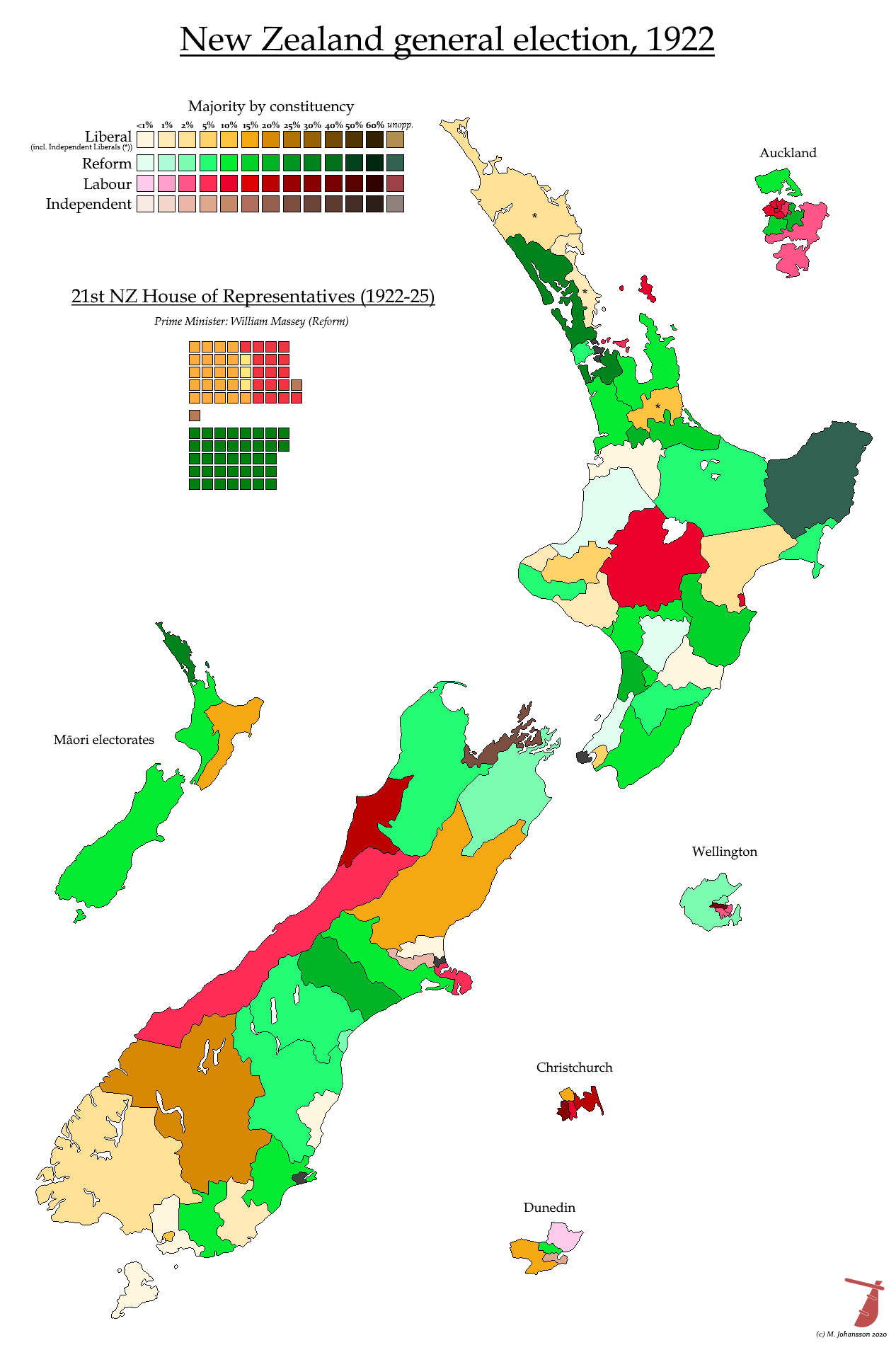

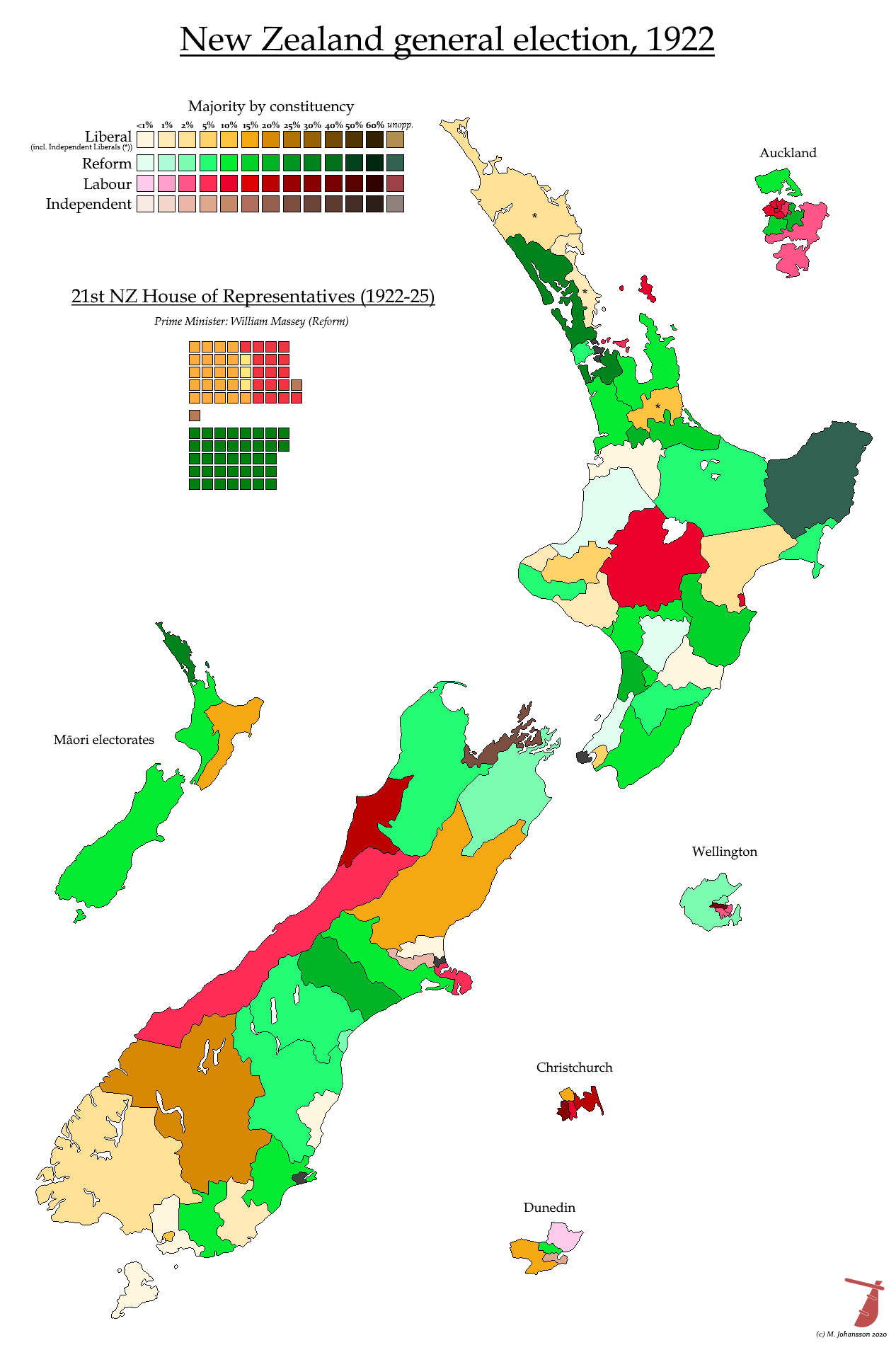

1922

Three years of a Reform majority, theoretically representing the freehold dairy farmers of the North Island more than anybody else, was ineffectual in the face of a global downturn in the export prices of agricultural produce, and the instinctively capitalist and free-trader Reformers began to experiment with statist solutions. The boards instituted during the Great War to organise the export and marketing of primary produce in Britain were kept on, and bolstered by continual small increases in the pensions payable to returned servicemen and the widows of those who did not return. Meanwhile, the scourge of Spanish Flu (introduced to New Zealand on the boat carrying Massey and Ward home from Europe) led to the creation of the Board of Health in 1920. It was all a little parsimonious, though, compared to the aspirations of some New Zealanders, and it was by now clear that no reform was coming from the Reform Government as it entered its second decade of office.

A typical example of the Reform Party striking towards state intervention without quite going far enough to make it work was in the sphere of settling returned servicemen on farms - combining the colonial urge to bring virgin land into production, while also serving as a glib answer to questions about rehabilitation into civvy street. The Government assistance was welcome, but it only went towards the cost of the land, and the soldiers would not only have to learn the skills of the job while trying to subsist on their farm, but they would also be lucky to be able to afford the machinery necessary to run a profitable modern farm. Many of these men were not suited for promotion to the yeomanry, and simply walked off their land.

Although the state of Massey's Government was poorer than in 1919 - and tarnished with the brushes of Little Englandism and sectarianism by its arrest of a Catholic Bishop for 'sedition' when he said something sceptical about the Anglo-Irish Treaty - their share of the vote increased slightly in 1922. The rise of Labour had raised questions about what exactly the alternative to Massey actually was. Moderate Liberal voters resiled at the thought of a Liberal-Labour coalition and jumped over to the Reformers, while those who favoured a progressive alliance were more likely than previously to vote tactically for the anti-Massey candidate with the best chance of winning. As such, despite Reform's improvement in voteshare, the Government fell backwards in terms of seats - down to 37 seats out of 80.

After the wartime coalition, many people had wondered why Reform and the Liberals didn't join forces against the Socialist menace. The new Liberal Leader, Thomas Wilford (Joseph Ward had lost his seat in 1919 and his successor had died), was torn. On the one hand, he attempted to pull back the progressive voters by renaming the party as the 'United Progressive Liberal and Labour Party' - but this would surely only have attracted people with a thirst for adjectives. After the election, he proposed 'fusion' with Reform, but they had a better idea.

Reform was four seats short of a majority, but there was by now a range of Independents and Independent Liberals who had quarreled with the new leadership or cut themselves loose from a sinking ship. Harry Atmore, who had voted for Massey in the second confidence vote in 1912 and was an intensely successful localist politician, was relatively easy to convince, while Allen Bell (who had unseated the ex-Liberal Reformer Vernon Reed in Bay of Islands as an Independent Liberal) was prevailed upon to join the Reform Party. More controversially, George Witty and Leonard Isitt abandoned their semi-detached positions in the Liberal Party to cross the floor. Isitt, in fact, was still a full member of the Party when he gave Massey his majority. He was an unlikely defector, to be sure: he had had a reputation as a radical during the Liberal Government and was a supporter of Prohibition - a cause which had now passed its high-water mark.

To make his Government more secure, Massey took the step - unprecedented in New Zealand - of seeking the election of a Speaker from outside his own Party. Speakers retain their party affiliations in New Zealand, and historically were allowed to speak in a partisan manner during Committees of the Whole. Massey's candidate was the Independent Charles Statham of Dunedin Central, who had left the Reform Party amid the Progressive incident of 1919 and subsequently tried to form the National Progressive and Moderate Labour Party with an Independent Labour MP in the city. It seems that 1922 was a boom year for adjectives. Statham turned out to be a traditionalist in the Chair, bringing back the official wig and commissioning a more impressive throne. He was supported also by the Liberals, and they kept him on when the Reform Government fell.

Although Labour stayed still in terms of raw vote, the Party doubled its seat count to 17. In Grey Lynn, John A. Lee (who had lost an arm in the War) defeated Reform's Clutha Mackenzie (blinded in the same War) and thereby gave Labour plausible deniability when it was accused of being a nest of simplistic pacifists. Elsewhere, the large rural seats of Waimarino and Westland fell to Labour, although their support with farmers was never strong and their main source of voters in these seats were railwaymen and miners respectively. However, these swathes of red would have produced a very positive emotional reaction among the Party's supporters.

The 1922 map is perhaps the clearest indication of the three-party nature of New Zealand politics in this period.

1919

The election scheduled for 1917 was delayed by two years due to the First World War - a crisis which tested the bluff dairy farmer Bill Massey beyond his expectations. He came through largely with flying colours, being respected at Imperial Conferences and loved by the troops on the front line, whom he made a point of visiting. In these overseas jaunts, he was joined by his Deputy, none other than Sir Joseph Ward. Ward (Liberal leader once more) joined in the wartime coalition government in 1915 and insisted on being treated as an equal to Massey wherever they went - much to the exasperation of other delegates to Conferences, who wanted small and effective meetings. Ward had a tendency to intervene late in the debate and make a long, rambling speech which largely went over ground already covered and which added virtually nothing, while the other Dominion representatives seethed and surreptitiously consulted their watches.

At the same time as the Reformers and Liberals temporarily put aside their differences, the Labour movement followed the same course on a more permanent basis. The existing Social Democratic and United Labour Parties united in 1916, forming the current Labour Party, and went on to encouraging successes in by-elections and in the 1919 general election, when they leaped up from a combined 8% of the vote to 24%, and 8 seats. Not all of the movement joined the Party, though: the idiosyncratic John Payne remained outside the tent due to his support for conscription and was defeated by the NZLP, while Bill Veitch of Wanganui went Independent due to his fundamental distaste for supporting strikers. Another pro-conscription Independent Labour candidate, Edward Kellett, unseated the Labour MHR for Dunedin North, while Sid Smith, elected as Independent Labour for New Plymouth, drifted to the Liberals shortly afterwards.

The Labour Party had been vocal and resolute in opposing conscription and calling for the conscription of wealth, to the extent that some of their leading figures were imprisoned for sedition. This included Peter Fraser (who was familiar with gaol due to his imprisonment over the 1913 Red Fed strike in Wellington), a future Prime Minister who - ironically - not only imposed conscription during the Second World War but staked his leadership on continuing it in peacetime. More significantly, the radical representative for the South Island mining seat of Grey, Paddy Webb, was imprisoned briefly for sedition and, after his release, refused to comply with his call-up papers. Seeking a mandate for his stand, he resigned and precipitated a by-election, in which he was returned unopposed as the Government refused to dignify it with a contest. Webb was sentenced to two years planting trees and a decade-long ban on holding public office, so at a second by-election Harry Holland - the Australian-born hardliner, soon to become a long-serving Labour Leader - entered Parliament.

While Labour united, the Reform Party almost split asunder. The necessity during the wartime coalition of finding places for Liberals in the Cabinet meant that ambitious Reformers would inevitably miss out. In early 1919 a group of these disgruntled backbenchers grouped together and began to talk about forming a Progressive Party - their platform was quite radical, proposing state control of agricultural export marketing, generous pensions and a state-owned shipping company. The last of these wasn't established until the Labour Government of the 1970s. The Progressives even began to scout out for a charismatic leader, landing on an Army General who had been at Gallipolli. However, events moved quicker than expected: Ward pulled the Liberals out of the Government and issued a manifesto closely based on the Progressive one, and Massey responded by appointing a couple of the rebels to vacant spaces in Cabinet. One of the ringleaders was frozen out of the Reform Party and the rest balked at explaining to the electorate why they had not simply joined the Liberals.

The Progressive incident was based in part upon the discontent that rural primary producers felt as a result of the post-war Depression, and it is no accident that the same period saw the emergence of the Progressive Party in Canada and the Country Party in Australia.

Another major change was that women now had the right to stand in parliamentary elections (they had gained the right to vote in advance of the 1893 poll, second only to Wyoming). Each of the three parties stood a single woman, but none were elected - and the first woman MP came only in 1933.

With the Liberals abandoning the centre ground and Labour splitting the vote on the left, Massey won a genuine majority for the first and only time during his two-decade spell in leadership. Even so, he won just 35% of the vote. But the Liberals unarguably had the worst of it: they fell to 19 seats and suffered the ignominy of losing their Leader, Sir Joseph Ward. His role would be filled by lesser men in the years to come.

1922

Three years of a Reform majority, theoretically representing the freehold dairy farmers of the North Island more than anybody else, was ineffectual in the face of a global downturn in the export prices of agricultural produce, and the instinctively capitalist and free-trader Reformers began to experiment with statist solutions. The boards instituted during the Great War to organise the export and marketing of primary produce in Britain were kept on, and bolstered by continual small increases in the pensions payable to returned servicemen and the widows of those who did not return. Meanwhile, the scourge of Spanish Flu (introduced to New Zealand on the boat carrying Massey and Ward home from Europe) led to the creation of the Board of Health in 1920. It was all a little parsimonious, though, compared to the aspirations of some New Zealanders, and it was by now clear that no reform was coming from the Reform Government as it entered its second decade of office.

A typical example of the Reform Party striking towards state intervention without quite going far enough to make it work was in the sphere of settling returned servicemen on farms - combining the colonial urge to bring virgin land into production, while also serving as a glib answer to questions about rehabilitation into civvy street. The Government assistance was welcome, but it only went towards the cost of the land, and the soldiers would not only have to learn the skills of the job while trying to subsist on their farm, but they would also be lucky to be able to afford the machinery necessary to run a profitable modern farm. Many of these men were not suited for promotion to the yeomanry, and simply walked off their land.

Although the state of Massey's Government was poorer than in 1919 - and tarnished with the brushes of Little Englandism and sectarianism by its arrest of a Catholic Bishop for 'sedition' when he said something sceptical about the Anglo-Irish Treaty - their share of the vote increased slightly in 1922. The rise of Labour had raised questions about what exactly the alternative to Massey actually was. Moderate Liberal voters resiled at the thought of a Liberal-Labour coalition and jumped over to the Reformers, while those who favoured a progressive alliance were more likely than previously to vote tactically for the anti-Massey candidate with the best chance of winning. As such, despite Reform's improvement in voteshare, the Government fell backwards in terms of seats - down to 37 seats out of 80.

After the wartime coalition, many people had wondered why Reform and the Liberals didn't join forces against the Socialist menace. The new Liberal Leader, Thomas Wilford (Joseph Ward had lost his seat in 1919 and his successor had died), was torn. On the one hand, he attempted to pull back the progressive voters by renaming the party as the 'United Progressive Liberal and Labour Party' - but this would surely only have attracted people with a thirst for adjectives. After the election, he proposed 'fusion' with Reform, but they had a better idea.

Reform was four seats short of a majority, but there was by now a range of Independents and Independent Liberals who had quarreled with the new leadership or cut themselves loose from a sinking ship. Harry Atmore, who had voted for Massey in the second confidence vote in 1912 and was an intensely successful localist politician, was relatively easy to convince, while Allen Bell (who had unseated the ex-Liberal Reformer Vernon Reed in Bay of Islands as an Independent Liberal) was prevailed upon to join the Reform Party. More controversially, George Witty and Leonard Isitt abandoned their semi-detached positions in the Liberal Party to cross the floor. Isitt, in fact, was still a full member of the Party when he gave Massey his majority. He was an unlikely defector, to be sure: he had had a reputation as a radical during the Liberal Government and was a supporter of Prohibition - a cause which had now passed its high-water mark.

To make his Government more secure, Massey took the step - unprecedented in New Zealand - of seeking the election of a Speaker from outside his own Party. Speakers retain their party affiliations in New Zealand, and historically were allowed to speak in a partisan manner during Committees of the Whole. Massey's candidate was the Independent Charles Statham of Dunedin Central, who had left the Reform Party amid the Progressive incident of 1919 and subsequently tried to form the National Progressive and Moderate Labour Party with an Independent Labour MP in the city. It seems that 1922 was a boom year for adjectives. Statham turned out to be a traditionalist in the Chair, bringing back the official wig and commissioning a more impressive throne. He was supported also by the Liberals, and they kept him on when the Reform Government fell.

Although Labour stayed still in terms of raw vote, the Party doubled its seat count to 17. In Grey Lynn, John A. Lee (who had lost an arm in the War) defeated Reform's Clutha Mackenzie (blinded in the same War) and thereby gave Labour plausible deniability when it was accused of being a nest of simplistic pacifists. Elsewhere, the large rural seats of Waimarino and Westland fell to Labour, although their support with farmers was never strong and their main source of voters in these seats were railwaymen and miners respectively. However, these swathes of red would have produced a very positive emotional reaction among the Party's supporters.

The 1922 map is perhaps the clearest indication of the three-party nature of New Zealand politics in this period.

Last edited:

More NZ, and thanks again to @Uhura's Mazda for the writeups.

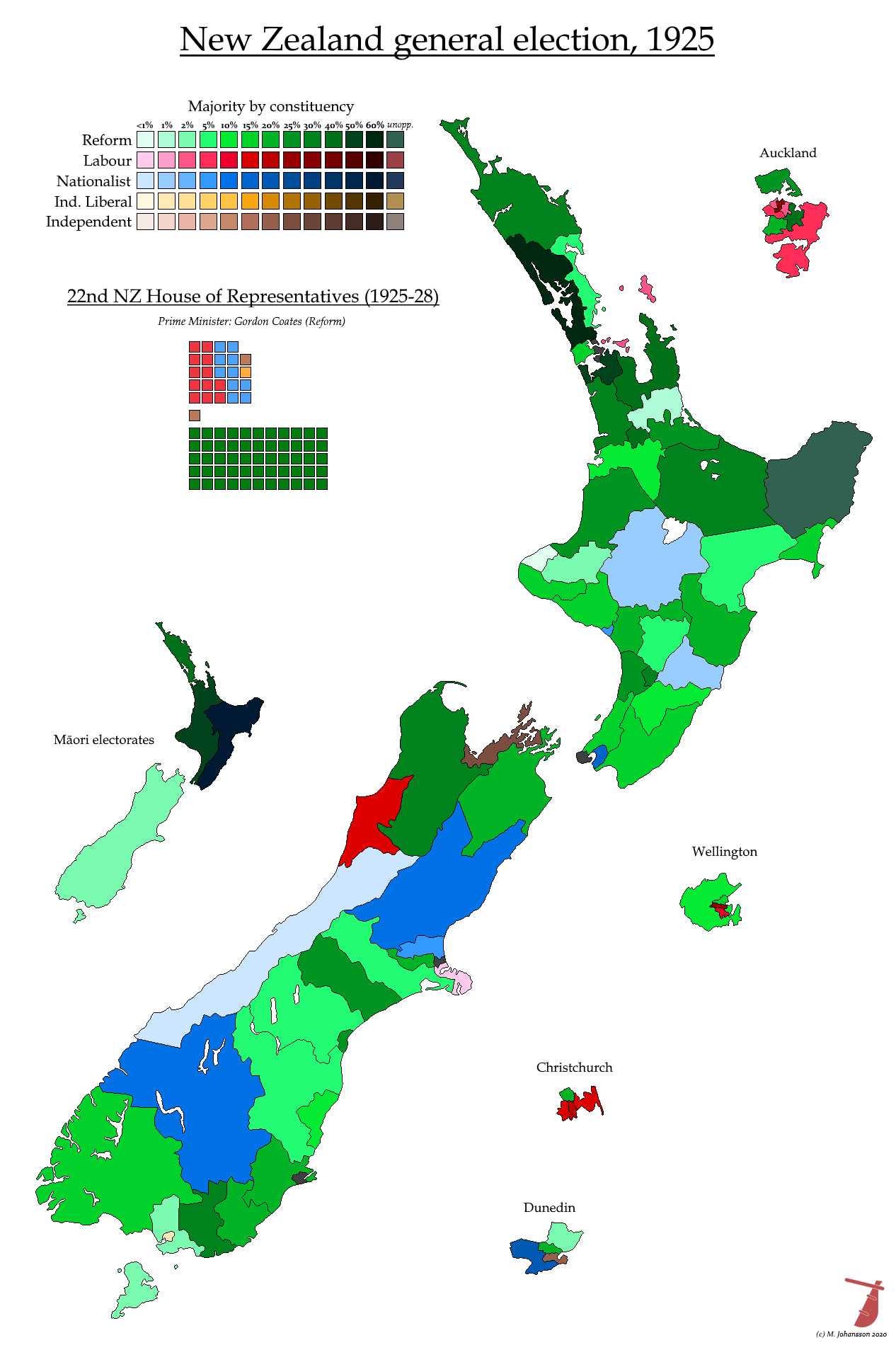

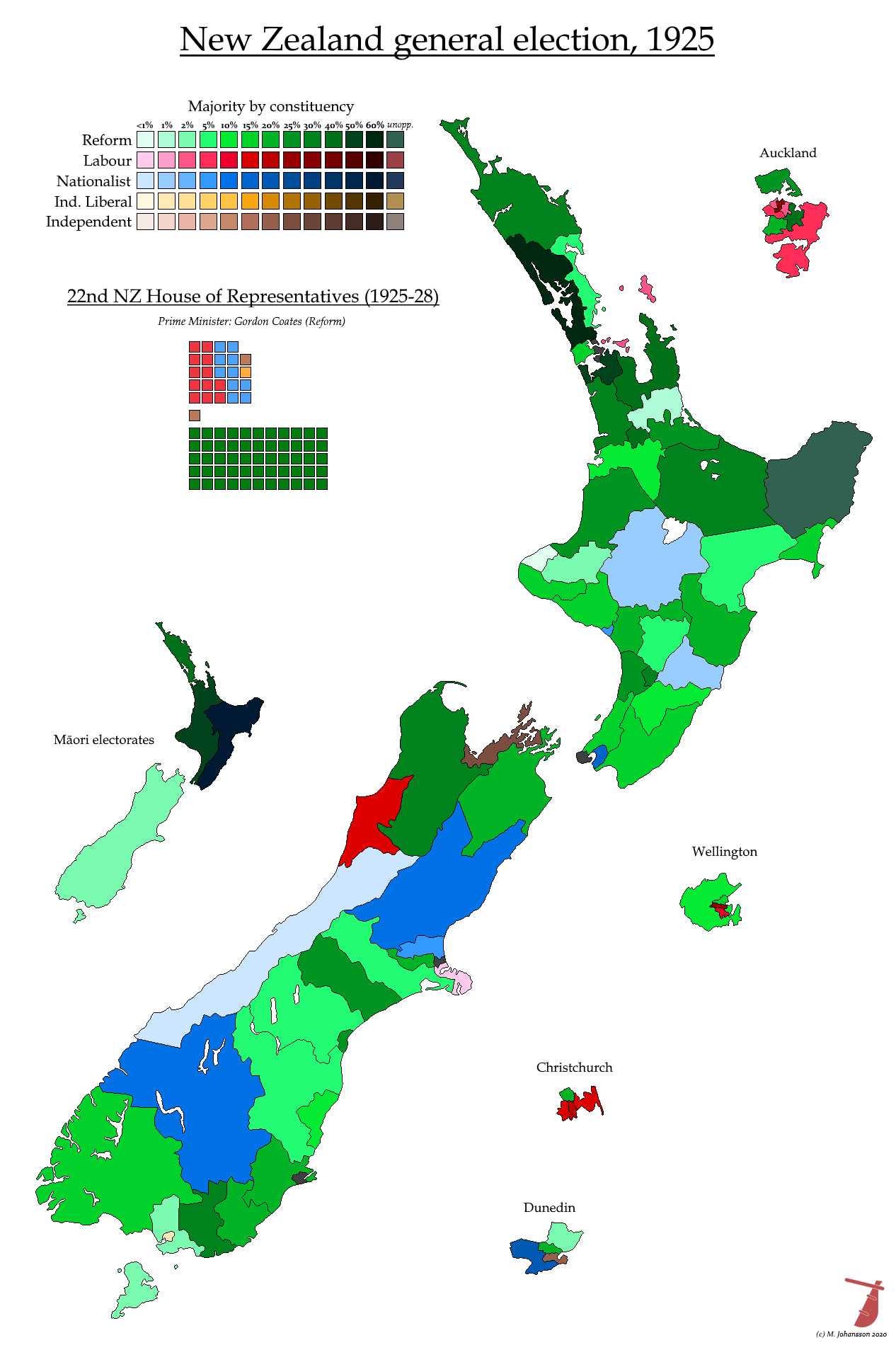

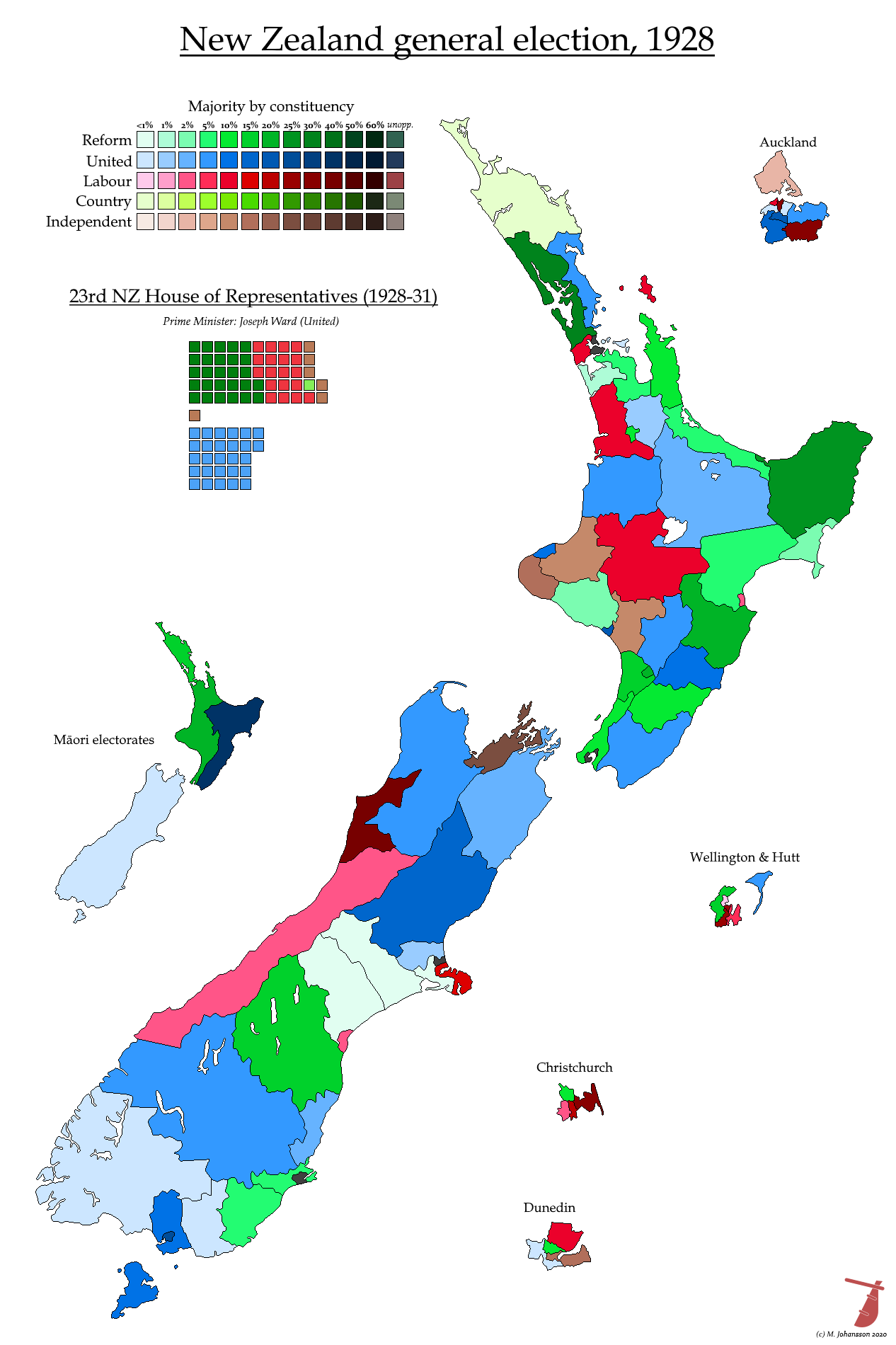

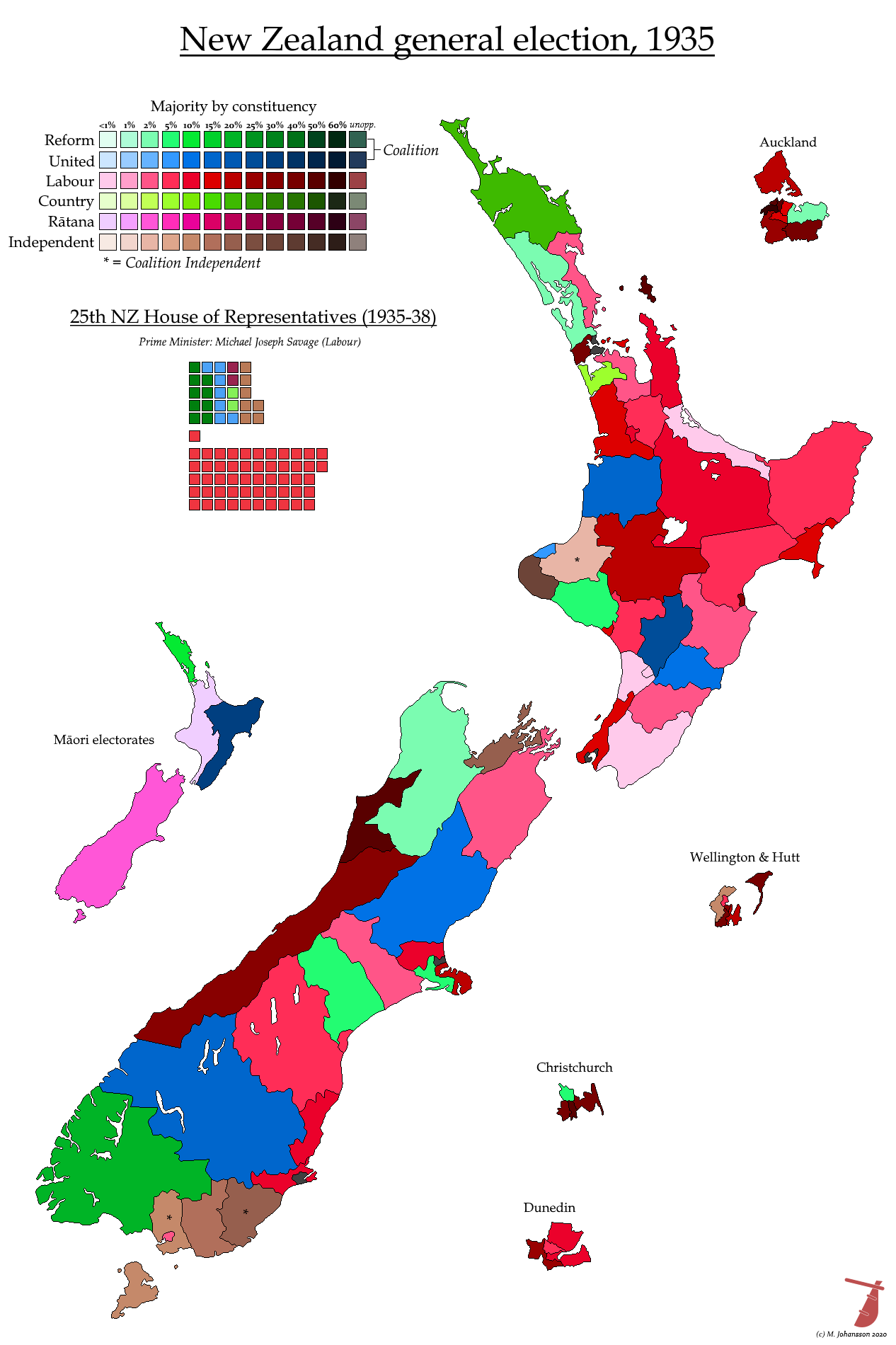

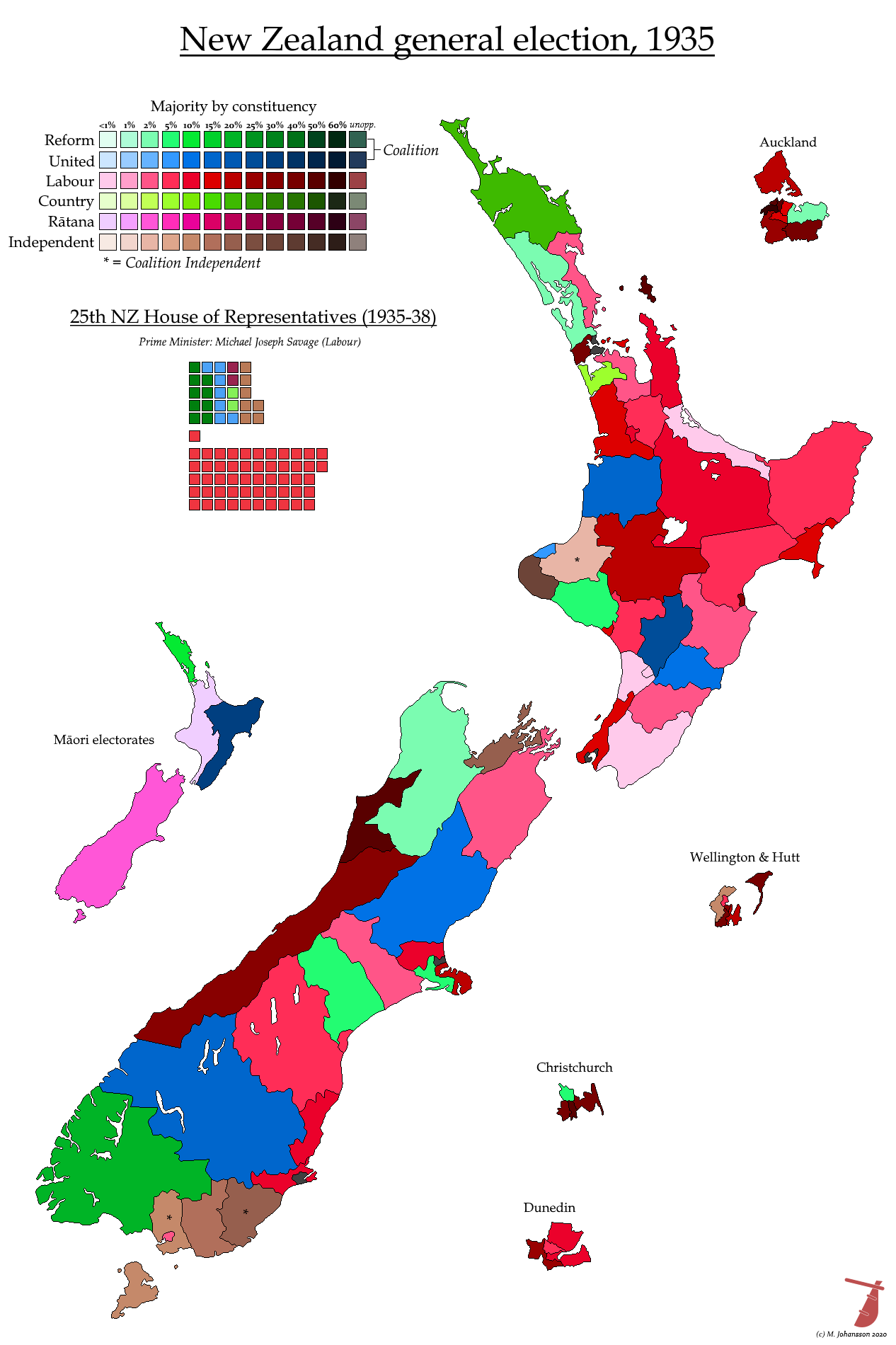

1925

1922 proved to be Farmer Bill Massey's last, rather anaemic, hurrah. He was dependent on the support of the crossbench and the two Liberals he'd won over, both of whom were rewarded for the treason with seats in the upper house and succeeded in their electorates by official Reformers. Massey became ill and retreated from public life in 1924 before dying early in the election year of 1925. Despite only winning a single majority at the polls, his time in office was second only to Richard Seddon's. Another similarity with Seddon - and with Ballance - was that he died in office while at least one potential successor was unready to participate in the battle for succession. To hold the fort, the elder statesman Sir Francis Bell stepped in on an interim basis to become simultaneously New Zealand's last Prime Minister from the upper house and its first Prime Minister to be born in New Zealand.

There were two front-runners. The closest thing the Reform Party had to an intellectual or an economist (very much of the laissez-faire stripe) was William Downie Stewart, who had only entered the House in 1919. However, he had developed rheumatoid arthritis during his War service and was often to be seen in an invalid chair. At the time of Massey's death, he was on a boat back from America, where he had been seeking a cure, and he sent a telegram advising the Reform caucus that he would happily serve under whomever they chose. In the event, only a tiny group of people around William Nosworthy disrupted the coronation of Gordon Coates.

Coates is an archetypal Kiwi PM - and like Bell, he was born in the country. He was brought up on a farm in Northland where he had learned to keep a bluff distance and a stiff upper lip. His lip was indeed rather stiff due to a childhood facial injury, and he grew a no-nonsense moustache to hide the disfigurement. Coates didn't know much about political theory, unlike Downie Stewart, but he had developed the reputation of a businesslike straight-shooter who didn't over-promise. This was clearly a resilient brand, as it grew despite the fact that he had shifted from being an Independent Liberal to putting Massey in power during his first few months as an MP.

Shortly afterwards, the Liberals also swapped out their leader. Thomas Wilford took the opportunity inherent in the death of the intransigent Massey to propose anew the idea of a 'fusion' between the non-Labour parties. For the first time, a working group of party bigwigs was set up, but it foundered upon the issue of a pre-election alliance, and it is unlikely that Coates was genuinely interested in the option. Wilford resigned in a fit of exasperation and was replaced by the stolid and unimaginative George Forbes. As a futile bid to argue the toss about the affair, the Liberals fought this election as the National Party, harking back to the wartime National Government, and fought the election on the basis of agreeing on virtually every policy with Reform and guilt-tripping them into fusion.