History Learner

Well-known member

One of the great "What Ifs" of WWII is the Battle of Kursk, arguably the largest land battle of the war and the second largest tank (by raw numbers) engagement after the Battle of Brody in 1941. Despite some tactical success, by the time the operation kicked off in July the Soviets were too prepared, resting in heavily defended positions and with a material as well numerical superiority over their attackers that precluded the hoped for strategic success. Given that, almost since the Battle itself ended, there has been a long running dispute between the men who were there and historians over whether success was possibly, usually in the context of an earlier offensive. Increasingly, I am convinced of the merits of this argument in that an earlier offensive would've yielded the Germans their operational goals for the most part.

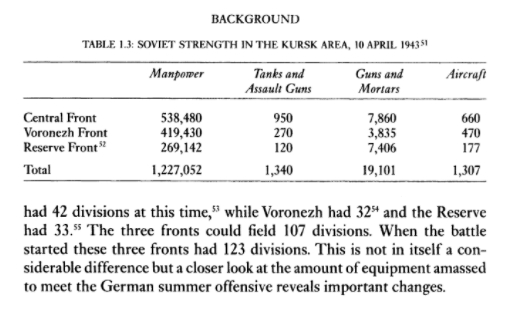

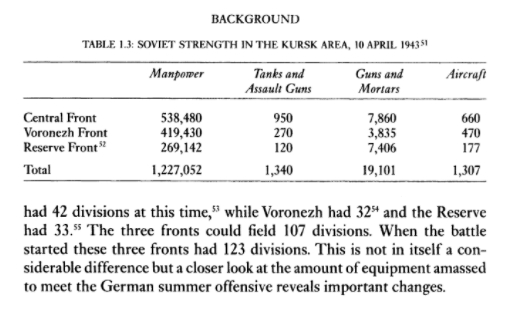

To begin with, here is a chart of Soviet strength circa April, 1943 taken from Kursk: A Statistical Digest -

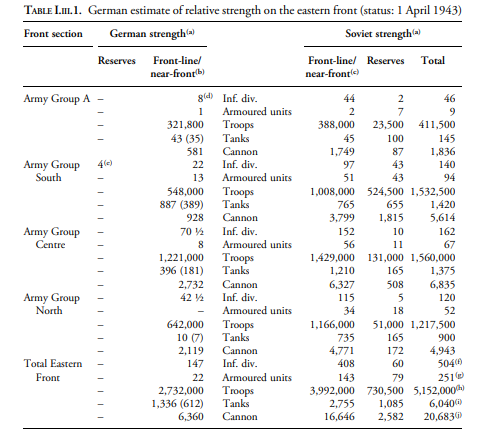

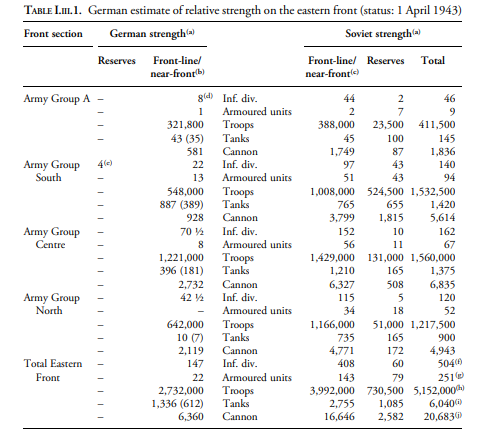

And here is another, taken from the Germany in the Second World War (Volume VIII) series concerning German front-wide strength at the start of April -

While not totally comparable, given the former focuses in on Soviet defenses in and around the Salient while the latter gives a front wide picture, it is useful to show the total availability of AFV strength and total strength for the Army Groups that did ultimately participate in Citadel historically at this time. We can, however, further it by expanding into citations from other sources, in this case being Kursk: The German View, concerning the German 9th Army of Army Group Center:

Further:

Finally:

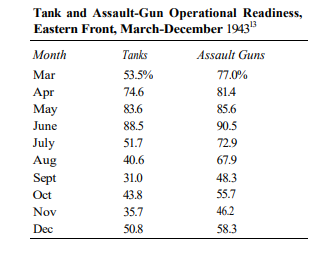

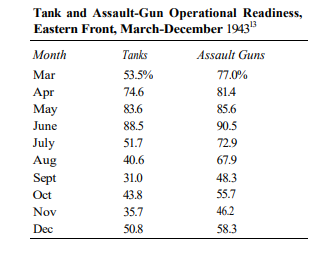

From this, we can thus firmly state that 9th Army was not essentially different from its July state in May of 1943 and, relative to the reduced Soviet position in May, would be definitively much stronger in a relative sense as it would be facing less Soviet opposition historically. This is important to note, as the Northern Pincer was the one that struggled the most historically, almost immediately breaking down into static fighting because of the concentrated Soviet opposition blocking its advance. Likewise, from the same source, we can also make a rough estimate of overall German AFV readiness by May:

This chart, which comes from Page 413, adds further context to overall German AFV strength about an earlier offensive. The earlier citation of said German strength was dated as to April 1st, and thus is overall more comparable to the March figure since the improvements of April overall had yet to happen. By May, as the figures show, the Germans were about as ready as they would later be in early July when the offensive kicked off. Utilizing the May figure, we thus find that of the total AFV count of 1,326 in April between Army Groups Center, South and A, that roughly 1,100 would be ready in May. Please take in note, this figure does not include delivery of fresh units in April or in the first portion of May.

Finally, I turn to Could Germany Have Won the Battle of Kursk if It Had Started in Late May or the Beginning of June 1943? which is an article by Valeriy N. Zamulin. Now, in the interests of intellectual honest, I want to state for the record Zamulin has taken the position, in this article, that he does not believe an earlier offensive would've made the difference. I fundamentally feel, however, that this is wrong based on the numbers he presents and then comparing them to the rest of the literature, in particular the facts I have already cited. Allow me to now quote from the article as to why I feel the numbers presented agree with my contention more than Zamulin's:

Further:

So Central Front is missing 60% of its AFVs and Voronezh Front is missing 24% of its AFVs, compared to the historical start date. These are serious, major lackings in combat formations that can have drastic impacts on the battle. It has already been shown, for example, that on the Northern Flank the Germans are much stronger, relative to historical levels, to Central Front and overall the AFV balance appears to be a tie in early May. Now, lastly, we must also cover defenses because historically the Soviets constructed a formidable, layered defense that helped to dissipate the German strength, leading to the overall Soviet success in the Battle:

Thus, we find decisive evidence that, in early May when the German attack was supposed to go forward originally, most of the defenses were not completed and still in poor shape, with mine laying significantly-around 80 or less-below the historical July state. It is worth noting that only the defenses the Germans historically broke through in July were completed by May, with the following belts which brought the Germans to a halt having not yet been finished and indeed, in many aspects far from it. I now ask the audience to ponder what that means when the Germans, with a tie in AFVs, break through said defenses and now have free reign in the Soviet rear without prepared defenses to halt such an action.

I thus fundamentally believe that, in such conditions, the Germans would've achieved their operational goal in terms of collapsing the Kursk Salient and mauling-if not destroying-all three Fronts contained within it. Such an action would serve to reduce the German front line in the East significantly, to the tune of freeing up 20 Divisions for the creation of a strategic reserve and allowing for a more compact, stable defensive line to emerge. While this would not have presented a decisive defeat to the USSR in terms of being a war winning blow directly, it would've established for the Germans the necessary strategic conditions to enforce a stalemate, preventing the Soviets from recovering the vital manpower and food resources of Ukraine, compounding the disaster from beyond the direct casualties inflicted upon them.

To begin with, here is a chart of Soviet strength circa April, 1943 taken from Kursk: A Statistical Digest -

And here is another, taken from the Germany in the Second World War (Volume VIII) series concerning German front-wide strength at the start of April -

While not totally comparable, given the former focuses in on Soviet defenses in and around the Salient while the latter gives a front wide picture, it is useful to show the total availability of AFV strength and total strength for the Army Groups that did ultimately participate in Citadel historically at this time. We can, however, further it by expanding into citations from other sources, in this case being Kursk: The German View, concerning the German 9th Army of Army Group Center:

Two months later, when Operation Citadel belatedly commenced on 5 July, how much stronger and better prepared was Ninth Army to achieve the objectives set for it? The army's combat strength had risen from 66,137 to 75,713 (a gain of 9,576), but this increase was deceiving. More than two-thirds of the additional strength (6,670 men) resulted not from replacements or reinforcements to the existing divisions but as the result of the addition of the 6th Infantry and 4th Panzer Divisions to the Ninth Army's administrative reporting system; only 2,906 new soldiers and returning convalescents had joined the ranks in the intervening two months. When the four divisions of XX Corps, which were assigned to hold Model's far right flank and take no part in the initial breakthrough phase of the battle, are discounted, Ninth Army jumped off toward Kursk on 5 July with a combat strength of only 68,747 troops.13

Further:

Ninth Army's transport situation improved only slightly between May and July. Model appears to have received about 1,200 additional motor vehicles in two months. Many undoubtedly were not new but stripped away from other units on Army Group Center's defensive fronts. Although the figure looks impressive at first glance, the actual gain in tactical mobility was only about 4-5 percent in each division. Calculated another way, each of the infantry divisions gained fewer than thirty vehicles; each of the panzer divisions received about 120.16

Finally:

To evaluate whether these increases were sufficient to warrant the repeated delay in launching Operation Citadel, inquiries must also be made into the extent to which the Red Army had reinforced opposite Ninth Army and—equally important—the success that the Germans had in recognizing that buildup. According to later intelligence reports, Army Group Center believed that the Soviets had increased their infantry strength north of Kursk from 124,000 to about 161,000 during the eight week hiatus.18 The overall quality of the new troops (many of whom were recent conscripts) was doubtful but, that caveat aside, these estimates meant that relative German combat strength had declined significantly due to the postponements of the attack. In May Ninth Army's combat strength by its own accounting was roughly 53.4 percent of that arrayed against it; by 4 July German strength as a percentage of Soviet numbers had dropped to just 47 percent. From an infantry perspective, attacking at a later date was a losing proposition.

Neither had Ninth Army's artillery buildup, as impressive as it may have seemed at the time, materially improved the odds of the offensive. The two armies holding the first defensive system immediately in Model's front (Thirteenth and Seventieth Armies), contained fewer than 3,000 guns and mortars as the Soviets enumerated them, the entire Central Front deploying less than 8,000. By 4 July, however, the Thirteenth and Seventieth Armies boasted 4,592 pieces of artillery, and Central Front's batteries had swollen to 12,453. Stated in the simplest terms, during the eight weeks in which the Germans moved up 362 new guns, the Russians brought forward 1,500 in the front line and 4,500 overall; as weak as Ninth Army had been in early May, it would have enjoyed far better prospects then for ultimate success.19

The story was much the same for armored fighting vehicles (AFVs). Contrary to German intelligence estimates, the Soviet Central Front had deployed only about 1,000 tanks and assault guns in late April-early May, rather than 1,500. This was a critical misinterpretation that explains much about Model's insistence on delaying the offensive. With 800 AFVs facing 1,500, the army commander had a legitimate case for arguing that additional panzers, especially Panthers and Tigers, were absolutely necessary for the assault. Had Model realized that Russian armored superiority was only about 200 vehicles, he would have been far more willing to proceed. By waiting, Ninth Army augmented its AFV holdings by about 25 percent, but the Soviets nearly doubled theirs. In early July, Central Front's advantage in tanks and self-propelled guns had increased from 200 to 700.

The overall conclusion must therefore be that the two-month delay materially contributed to the early failure of Ninth Army's attack. In all three critical categories—combat troops, artillery, and armor—the modest gains in strength that the Germans managed were more than offset by Soviet reinforcements. Model diminished his own army's chance of breaking through Central Front's defenses by convincing Hitler to postpone Operation Citadel. Given the faulty intelligence estimates with which he was working, however, the army commander's reasoning appeared to have merit, and in late spring 1943 few German officers yet realized the depth of Soviet resources.

From this, we can thus firmly state that 9th Army was not essentially different from its July state in May of 1943 and, relative to the reduced Soviet position in May, would be definitively much stronger in a relative sense as it would be facing less Soviet opposition historically. This is important to note, as the Northern Pincer was the one that struggled the most historically, almost immediately breaking down into static fighting because of the concentrated Soviet opposition blocking its advance. Likewise, from the same source, we can also make a rough estimate of overall German AFV readiness by May:

This chart, which comes from Page 413, adds further context to overall German AFV strength about an earlier offensive. The earlier citation of said German strength was dated as to April 1st, and thus is overall more comparable to the March figure since the improvements of April overall had yet to happen. By May, as the figures show, the Germans were about as ready as they would later be in early July when the offensive kicked off. Utilizing the May figure, we thus find that of the total AFV count of 1,326 in April between Army Groups Center, South and A, that roughly 1,100 would be ready in May. Please take in note, this figure does not include delivery of fresh units in April or in the first portion of May.

Finally, I turn to Could Germany Have Won the Battle of Kursk if It Had Started in Late May or the Beginning of June 1943? which is an article by Valeriy N. Zamulin. Now, in the interests of intellectual honest, I want to state for the record Zamulin has taken the position, in this article, that he does not believe an earlier offensive would've made the difference. I fundamentally feel, however, that this is wrong based on the numbers he presents and then comparing them to the rest of the literature, in particular the facts I have already cited. Allow me to now quote from the article as to why I feel the numbers presented agree with my contention more than Zamulin's:

The replenishment of Rokossovsky’s and Vatutin’s forces with tanks didn’t go so smoothly or swiftly. On 3 May the Central Front had 674 tanks and 38 self-propelled artillery vehicles, or 40 percent of their availability on 5 July, while the 13th Army had 137 tanks,11 or 64 percent of the number it had by the start of the battle. However, the situation with armor on the southern shoulder of the Kursk bulge at this time was significantly better.

Further:

Thus at the beginning of May, the Central Front was substantially weaker than its neighbor: On 15 May the Voronezh Front had 1,380 serviceable tanks and self-propelled guns, or 76 percent of that number that it would receive by the start of the Battle of Kursk, while the Central Front had twice fewer.

So Central Front is missing 60% of its AFVs and Voronezh Front is missing 24% of its AFVs, compared to the historical start date. These are serious, major lackings in combat formations that can have drastic impacts on the battle. It has already been shown, for example, that on the Northern Flank the Germans are much stronger, relative to historical levels, to Central Front and overall the AFV balance appears to be a tie in early May. Now, lastly, we must also cover defenses because historically the Soviets constructed a formidable, layered defense that helped to dissipate the German strength, leading to the overall Soviet success in the Battle:

It was not only the condition of our forces in the Kursk area that notably contributed to the failure of Operation Citadel, but also the skillfully constructed, deeply echeloned defenses. Although the German general and Western scholars almost never point to this factor as the decisive one in the Wehrmacht’s failure, I nevertheless consider it important to stop here and give it brief consideration. If the main efforts of both N. F. Vatutin and K. K. Rokossovsky in May–June 1943 are analyzed in detail, it is clear that they were directed toward improving the defensive lines and training the troops to use them effectively. There were also serious objective reasons for this. For example, as the inspections conducted in the first half of May by commissions sent from the General Staff testify, almost all the work on the first and second lines in the armies’ main belt of defenses in the Voronezh Front’s sector had been completed. As concerns the second and third belts, here the commissions found substantial, although not critical, shortcomings in their construction and layout (light mine laying in the zone between the belts, shallow trenches, poor camouflage, etc.), which had already to a significant degree been eliminated by the beginning of June. For example, prior to 5 May the 6th Guards Army had managed to deploy only 17 percent of its 90,000 anti-tank mines and 16 percent of its 64,000 anti-personnel mines, which nevertheless were all emplaced by 5 July. In the 7th Guards Army, the given indicators were also extremely low on 16 May, though higher than its neighbor’s: Approximately 22.4 percent of its 65,000 anti-tank mines and 16.9 percent of its 84,000 anti-infantry mines had been laid.23 Yet by 5 June, this situation had also sharply changed: the 6th Guards Army had carried out 50 percent of the plan regarding anti-tank mines and 62 percent of the plan regarding anti-personnel mines. The corresponding figures for the 7th Guards Army were 46.2 percent and 35.7 percent respectively.

Thus, we find decisive evidence that, in early May when the German attack was supposed to go forward originally, most of the defenses were not completed and still in poor shape, with mine laying significantly-around 80 or less-below the historical July state. It is worth noting that only the defenses the Germans historically broke through in July were completed by May, with the following belts which brought the Germans to a halt having not yet been finished and indeed, in many aspects far from it. I now ask the audience to ponder what that means when the Germans, with a tie in AFVs, break through said defenses and now have free reign in the Soviet rear without prepared defenses to halt such an action.

I thus fundamentally believe that, in such conditions, the Germans would've achieved their operational goal in terms of collapsing the Kursk Salient and mauling-if not destroying-all three Fronts contained within it. Such an action would serve to reduce the German front line in the East significantly, to the tune of freeing up 20 Divisions for the creation of a strategic reserve and allowing for a more compact, stable defensive line to emerge. While this would not have presented a decisive defeat to the USSR in terms of being a war winning blow directly, it would've established for the Germans the necessary strategic conditions to enforce a stalemate, preventing the Soviets from recovering the vital manpower and food resources of Ukraine, compounding the disaster from beyond the direct casualties inflicted upon them.

Last edited: