I was working on some old congressional elections, but I decided to move over to a country that makes more sense.

Indonesia is the world's fourth-largest country by population, and will very likely become the third-largest within a few decades. The majority of its population live on the island of Java, whose 140 million inhabitants cram themselves onto an island the size of England (not Great Britain,

England). The tropical climate and strong, predictable monsoons make Java extremely fertile ground for rice cultivation, which is the island's main agricultural staple and the reason it supports such a massive population. Java is culturally divided between its eastern two-thirds, whose inhabitants speak Javanese, and its western third, whose inhabitants speak Sundanese. Both groups use Indonesian as a lingua franca, and both groups are overwhelmingly Muslim, falling along a spectrum between the more syncretic traditional practices of the

abangan and the more orthodox "modernist" Islam of the

santri. Jakarta additionally has well-established Chinese and Malay communities, and Christianity has a lingering presence from colonial times but doesn't quite dominate any part of Java the way it does some of the outlying Indonesian islands.

The politics of Java reflect its ethnic and cultural divides, with the Sundanese-speaking regions traditionally divided between moderate Islamists and right-wing secular nationalists, while the rural Javanese-speaking central region was the main stronghold of the Indonesian Communist Party until its dissolution and mass murder at the hands of the Army in the 1960s. The eastern end of the island, which is divided between Javanese and Madurese (an ethnic group originating on the neighbouring island of Madura), is known as a stronghold of the Nahdlatul Ulama movement, a moderate

santri Islamic movement whose members (mostly) support a tolerant, pluralistic ideal of Islamic culture.

How does this translate to the electoral map, then? Well, Indonesia has gone through some things over its seventy-five years of independence, and of the countries I've mapped thus far, it probably most closely resembles Brazil - it's a young democracy whose party system mostly lives in the shadow of the former military dictatorship. In Indonesia, this was the New Order (

Orde Baru) of President Suharto, who ruled from 1967 until 1998. Suharto took a pretty dim view of democracy in general, but he did allow closely-managed legislative elections between three state-sanctioned political parties - the

United Development Party (

Partai Persatuan Pembangunan,

PPP), a holding pen for Islamists, the

Indonesian Democratic Party (

Partai Demokrasi Indonesia,

PDI), which started out as a holding pen for secular nationalists but became dominated by the centre-left brand of such favoured by former president Sukarno and his daughter Megawati, and the

Functional Groups (

Golongan Karya,

Golkar), a "non-party" composed of different social corporations who held a majority in the legislature throughout Suharto's rule, and had no proper ideology beyond vaguely-authoritarian capitalist developmentalism - the "functional group" that controlled the organisation in practice was the military.

After the 1997 Asian financial crisis brought down Suharto's government, free elections were held in 1999, and these featured a number of new parties in addition to the main three (Megawati rechristened the PDI as the

Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (

Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan,

PDI-P), but the PPP and Golkar carry on under their old names):

- The

National Awakening Party (

Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa,

PKB) was established by NU leader Abdurrahman Wahid (also known as "Gus Dur"), and is essentially the political vehicle for the NU in about the same way as the Komeito in Japan is for Soka Gakkai. As such, they support a moderate "Islamic democracy", wanting a bigger role for Islam in Indonesian society and politics but stopping short of calling for an Islamic republic. Wahid was elected President by the legislature in 1999, but had to resign in 2001 after a corruption scandal, being replaced by Megawati, who had served as his vice-president.

- The

National Mandate Party (

Partai Amanat Nasional,

PAN) is also a moderate Islamist party, but is supported by the Muhammadiyah organisation rather than NU and draws more support off Java.

- The

Justice and Prosperity Party (

Partai Keadilan Sejahtera,

PKS) subscribes to a more radical form of Islamism, inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and while it doesn't outright support a Sharia-based Islamic republic, it's usually considered the most hardline of Indonesia's Islamist parties.

- The

Democratic Party (

Partai Demokrat) entered the scene in 2004 as the vehicle for Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono's candidacy in the first direct presidential elections in Indonesian history, in which Yudhoyono defeated Megawati convincingly. During his ten-year presidency, it became something of a party of power, replacing Golkar's authoritarian corporatism with neoliberal secular nationalism.

- The

NasDem Party (

Partai NasDem) is a political vehicle for media mogul Surya Paloh, who had previously been a Golkar member, and as you might expect from all these factors, it has no real ideology beyond vague secular nationalism. With Yudhoyono leaving office in 2014, there's now very little to distinguish NasDem from the Democrats (or, indeed, Golkar) in practice.

- Finally, the

Party of the Great Indonesia Movement (

Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya,

Gerindra) is a political vehicle for General Prabowo Subianto, Suharto's former son-in-law and one of the principal movers-and-shakers in the late New Order's military support organisation. Prabowo formed a united front with Megawati to oppose Yudhoyono's re-election efforts in 2009, but after this failed spectacularly, Prabowo and the PDI-P fell out and Gerindra became one of the two principal players in presidential politics. Prabowo ran for president in 2014 and 2019, losing both times to the PDI-P's Joko Widodo.

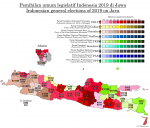

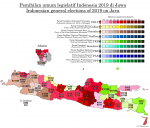

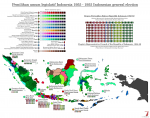

In 2019, the legislature was elected on the same day as the President for the first time ever, and Jokowi cruised to re-election against Prabowo backed by all parties except Gerindra, the Democrats, the PAN and the PKS. The PDI-P made significant gains and defended its first-place status from 2014, helped by a strong showing in Javanese-speaking central and east Java, especially so around Jokowi's home region of Surakarta. Prabowo's popularity in west Java reflected itself in good results for Gerindra there, while the PKB did well in the NU strongholds in the east. The PAN and PKS took most of the Islamic vote in west Java, the PKS in particular getting first-place results in Bandung and suburban Jakarta.