Vying for power

No one held a majority in Britain's hung parliament. Whilst a number of constituencies conducted re-counts and the parties dusted themselves down from spectacular gains, beatings and lost deposits, the momentous nature of 1987 grew manifest. More female candidates stood and were elected than ever before. Labour women accompanied Alliance radicals inspired by Shirley Williams, progressive Conservatives and Unionist mini-Thatchers. The SDP promoted people into politics from all walks of life. Teachers, doctors, barristers, social workers and pillars of their local community brought real expertise to parliament. The Benn project had invited Militant to steer a campaign for democratic socialism. The UK got its first Communist-backed MPs since 1950. Right-wing factional organiser John Spellar bitterly suggested that Labour had been infiltrated and taken over by entryists, Red Front "Trots" and Soviet agents. Tony Benn was “the most dangerous man in Britain”. Mr. Benn fought back stridently against such trumped up charges. Labour was projected to be the largest single party in the House of Commons, he reminded a press conference, televised live from Bristol around 7 am on Friday 3 July. His party therefore had the right to seek to form a government with a clear popular mandate.

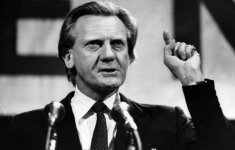

The Labour leader’s remarks enflamed the day’s news coverage. True comrades such as Eric Heffer, Ken Livingstone and John Prescott set out the party line. Senior Alliance, Tory and Unionist representatives denied and debated Labour’s achievement, particularly Liberals and Social Democrats vying for power in the post-election fall-out. Enoch Powell told the media: “We campaigned on behalf of working-class voters who have been neglected and taken for granted for decades. We’ve provided hope and truth for the electorate and driven the political agenda.” Michael Heseltine tried valiantly to spin the dire state of the Conservatives: “In many seats we are the real opposition. This is true of both northern England, where we have crushed the splitters, and in southern England, where we are the opposition to the Alliance.” David Steel and Roy Jenkins rejected Benn's case outright: “People just re-elected the only team able to heal social division. Moderates and socialists from across the nation have united with a resurgent Liberal Party. The Alliance mounted a successful challenge to our class-based system of politics in Britain. Be in no doubt: there is now the prospect of another Liberal/Social Democratic partnership government.”

The Labour leader’s remarks enflamed the day’s news coverage. True comrades such as Eric Heffer, Ken Livingstone and John Prescott set out the party line. Senior Alliance, Tory and Unionist representatives denied and debated Labour’s achievement, particularly Liberals and Social Democrats vying for power in the post-election fall-out. Enoch Powell told the media: “We campaigned on behalf of working-class voters who have been neglected and taken for granted for decades. We’ve provided hope and truth for the electorate and driven the political agenda.” Michael Heseltine tried valiantly to spin the dire state of the Conservatives: “In many seats we are the real opposition. This is true of both northern England, where we have crushed the splitters, and in southern England, where we are the opposition to the Alliance.” David Steel and Roy Jenkins rejected Benn's case outright: “People just re-elected the only team able to heal social division. Moderates and socialists from across the nation have united with a resurgent Liberal Party. The Alliance mounted a successful challenge to our class-based system of politics in Britain. Be in no doubt: there is now the prospect of another Liberal/Social Democratic partnership government.”

Last edited: