-

Hi Guest!

The costs of running this forum are covered by Sea Lion Press. If you'd like to help support the company and the forum, visit patreon.com/sealionpress

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

WI: Larger Mexican Cession?

- Thread starter Deceptacon

- Start date

JesterBL

Gastronaut

- Location

- Flyover Country, USA

- Pronouns

- he/him

I will say, Tampico's development as a border town and major port is fascinating to me, especially because it will get a solid 30 or so years of oil wealth in any TL.

Jackson Lennock

Well-known member

Stepping away from my Second Mexican Empire idea,

The dilemma is that California is already a free state upon admission. It seems to me that "Colorado" would be a doughface state at most.

Mining operations don't have the same margins as cotton. That it would be lucrative for some is not the same is it being lucrative to the point of being able to dominate in a way akin to the American southeast of OTL.

The Fugitive Slave Act is in itself a pretty big deal. The increasing southern demand that Slaveholders have rights to bring their slaves into northern states and that the northern and national government provide additional support is itself a pretty contentious thing. So is the practice of people running north to kidnap free blacks. Dred Scott essentially made popular sovereignty a constitutional requirement. What's to stop the Taney Court from taking the actions it did OTL: saying Blacks could never be citizens (and thus never be allowed in Federal Court) and that Congress could not deprive them of their right in property by creating free states. And the case of Lemon v New York was already teeing up the idea that slaveholders had a right to bring their slaves into free states when they traveled.

It is also worth accounting that the attempt to extend the Missouri Compromise line to the pacific already failed OTL. Stephen Douglas proposed the compromise line in 1848, and it was voted down 109 to 82. The Wilmot Proviso passed 115-106 but proceeded to be rejected in the Senate. The rumbling to oppose the *expansion* of slavery already existed, and were not limited to mere expansion into Kansas and Nebraska. Maybe there would be popular sovereignty in the states acquired from Mexico, but that still is a cauldron for conflict.

I also fail to see why moral developments of OTL would not continue. The immorality of slavery will grow as a political issue in the north over time even if the Southern states don't see the threat of being outvoted in the Senate. If it is not the Kansas-Nebraska Act that kills the Whigs, it will be something else.

Even if the parties remain bisectional (which I question, since the Whig policy on slavery amounted to not talking about it out of fear that it would divided the party - which is why they nominated 'nobody knows what he actually thinks' Zachary Taylor to avoid the issue), the north will be more populous and antislavery forces can win at nominating conventions. If any slave states flip (as I believe at least some eventually would), then I see the issue boiling over.

You showed me something from *Kentucky,* a state which received little immigration. Delaware, meanwhile, voted against manumission by just a single vote OTL in 1847.

I emphasize that Missouri, Maryland, and Delaware - states which did receive immigration - probably would shift into the free column over time. Most likely in the 1870s or 1880s.

I suspect it would be extended to the Pacific, given the greater land available here. The Compromise of 1850 makes sense when extending the line of the Pacific would mean four or five more Slave States for the South; by leaving the issue undecided, it left open the prospect that territory like Kansas could become Slave States later on. Here, with all of Northern Mexico annexed there is a reasonable prospect both sides can continue adding States on a 1:1 rate and thus use the pre-existing Compromise.

The dilemma is that California is already a free state upon admission. It seems to me that "Colorado" would be a doughface state at most.

For agriculture, yes, but there is also mining available. In particular, exploiting Slave labor to get at Sonoran silver comes to mind.

Mining operations don't have the same margins as cotton. That it would be lucrative for some is not the same is it being lucrative to the point of being able to dominate in a way akin to the American southeast of OTL.

I don't see this as likely because, outside of the Fugitive Slave Act, the South has nothing left to lobby for internally here and the key demands of the Northern Public-of the West being Free Soil for Northern farmers-has been met. Likewise, by retaining the Whig Party, both major parties remain bisectional and thus Southern support will remain a factor for every candidate to consider. Even if that proves unfounded, a 1:1 rate in States for the Senate means Southern interests, as defined by the Planters, will continue to be met. Any Anti-Slavery agenda will go to the Upper House to die.

The Fugitive Slave Act is in itself a pretty big deal. The increasing southern demand that Slaveholders have rights to bring their slaves into northern states and that the northern and national government provide additional support is itself a pretty contentious thing. So is the practice of people running north to kidnap free blacks. Dred Scott essentially made popular sovereignty a constitutional requirement. What's to stop the Taney Court from taking the actions it did OTL: saying Blacks could never be citizens (and thus never be allowed in Federal Court) and that Congress could not deprive them of their right in property by creating free states. And the case of Lemon v New York was already teeing up the idea that slaveholders had a right to bring their slaves into free states when they traveled.

It is also worth accounting that the attempt to extend the Missouri Compromise line to the pacific already failed OTL. Stephen Douglas proposed the compromise line in 1848, and it was voted down 109 to 82. The Wilmot Proviso passed 115-106 but proceeded to be rejected in the Senate. The rumbling to oppose the *expansion* of slavery already existed, and were not limited to mere expansion into Kansas and Nebraska. Maybe there would be popular sovereignty in the states acquired from Mexico, but that still is a cauldron for conflict.

I also fail to see why moral developments of OTL would not continue. The immorality of slavery will grow as a political issue in the north over time even if the Southern states don't see the threat of being outvoted in the Senate. If it is not the Kansas-Nebraska Act that kills the Whigs, it will be something else.

Even if the parties remain bisectional (which I question, since the Whig policy on slavery amounted to not talking about it out of fear that it would divided the party - which is why they nominated 'nobody knows what he actually thinks' Zachary Taylor to avoid the issue), the north will be more populous and antislavery forces can win at nominating conventions. If any slave states flip (as I believe at least some eventually would), then I see the issue boiling over.

Slavery was becoming more entrenched in the Border States at this time, not less.

Rethinking the Coming of the Civil War: A Counterfactual Exercise by Gary J. Kornblith, Journal of American History (Volume 90, No. 1, June 2003):

You showed me something from *Kentucky,* a state which received little immigration. Delaware, meanwhile, voted against manumission by just a single vote OTL in 1847.

I emphasize that Missouri, Maryland, and Delaware - states which did receive immigration - probably would shift into the free column over time. Most likely in the 1870s or 1880s.

History Learner

Well-known member

The dilemma is that California is already a free state upon admission. It seems to me that "Colorado" would be a doughface state at most.

The Mexican Cession was in 1848, California did not enter the Union until 1850. Likewise, the proposal to split off Southern California to form a new state was from the late 1850s, so California's admission isn't a set deal and could certainly be changed later. As for "Colorado", the area was largely settled by Southerners and was extremely Pro-Southern in feeling, as evidenced by the fact Pro-Confederate militias were raised during the Civil War and had to be dispersed by units raised from Northern California.

Mining operations don't have the same margins as cotton. That it would be lucrative for some is not the same is it being lucrative to the point of being able to dominate in a way akin to the American southeast of OTL.

Proto Industrial activities, such as mining, did generally have the same rates of return as Cotton on average. The 1850s Boom in Cotton was an anomaly that produced distortions; the South actually lost industry over the course of that decade because of this.

The Fugitive Slave Act is in itself a pretty big deal. The increasing southern demand that Slaveholders have rights to bring their slaves into northern states and that the northern and national government provide additional support is itself a pretty contentious thing. So is the practice of people running north to kidnap free blacks. Dred Scott essentially made popular sovereignty a constitutional requirement. What's to stop the Taney Court from taking the actions it did OTL: saying Blacks could never be citizens (and thus never be allowed in Federal Court) and that Congress could not deprive them of their right in property by creating free states. And the case of Lemon v New York was already teeing up the idea that slaveholders had a right to bring their slaves into free states when they traveled.

For one, the fact the national environment that provoked said court cases is completely different. They did not appear from the ether, but were instead an end result of escalating sectional tensions engendered by the conflict over limited space/land. Without the dissolution of the Whigs and the rise of the Free Soil Republicans, the Southern Moderate faction will still be around and powerful.

It is also worth accounting that the attempt to extend the Missouri Compromise line to the pacific already failed OTL. Stephen Douglas proposed the compromise line in 1848, and it was voted down 109 to 82. The Wilmot Proviso passed 115-106 but proceeded to be rejected in the Senate. The rumbling to oppose the *expansion* of slavery already existed, and were not limited to mere expansion into Kansas and Nebraska. Maybe there would be popular sovereignty in the states acquired from Mexico, but that still is a cauldron for conflict.

Indeed it failed, and it's obvious to see why; the extension of the 1820 Compromise Line would have allowed the addition of three Slave States (New Mexico, Arizona and SoCal/"Colorado") while allowing for about 15 Free States. It would've completely ended the prospect of Balance in the Senate upon which the South was depending upon, as exemplified in how the Senate was used to check the Wilmot Proviso. The rumbling to oppose Slavery was on Free Soil principles; Northerners were not abolitionists at this time, but were opposed to competition with Slave labor in the Great Plains.

I also fail to see why moral developments of OTL would not continue. The immorality of slavery will grow as a political issue in the north over time even if the Southern states don't see the threat of being outvoted in the Senate. If it is not the Kansas-Nebraska Act that kills the Whigs, it will be something else.

Because their catalysts are removed. Even after the bitter political conflict of the 1850s, including Bleeding Kanasas, it took four years of war and hundreds of thousands of dead to push the nation in favor of Abolitionism and even then, this was a strong struggle in 1865. Outside of Slavery, I can think of no other pressing political conflict of the day that could invoke such a split. Tariffs usually get invoked in Lost Cause mythology, but the Whig Party had a strong Southern following that was also Pro Tariff.

Even if the parties remain bisectional (which I question, since the Whig policy on slavery amounted to not talking about it out of fear that it would divided the party - which is why they nominated 'nobody knows what he actually thinks' Zachary Taylor to avoid the issue), the north will be more populous and antislavery forces can win at nominating conventions. If any slave states flip (as I believe at least some eventually would), then I see the issue boiling over.

Given nominating conventions were controlled by the parties themselves at this time, rather than popular vote, I don't see that as an issue. Likewise, it becomes less of an issue if the South has maintained parity in the Senate. Part of the concern with Lincoln was the expectation all remaining territories would go Free, which would tilt the balance against the South.

You showed me something from *Kentucky,* a state which received little immigration. Delaware, meanwhile, voted against manumission by just a single vote OTL in 1847.

Actually, it talked about Kentucky and Delaware:

"Yet without the Civil War, it seems highly unlikely that the states of the border South would have acted to abolish slavery anytime soon. Antislavery forces were growing weaker, not stronger, in the region at midcentury. In 1851 Cassius Clay, a gradualist, lost his bid for the governorship of Kentucky by an overwhelming margin. "Even in Delaware," Freehling acknowledged, 'where over fifteen thousand slaves in 1790 had shrunk to under two thousand in 1860, slaveholders resisted final emancipation"--and they did so successfully until 1865. Perhaps most revealing of all was President Lincoln's failure to persuade border South congressmen to support gradual, compensated emancipation. Had the United States followed the Brazilian path to abolition, the South's peculiar institution would almost surely have persisted beyond 1900."

An additional 18 years of immigration and development failed to break Planter power in Delaware, so I'm not sure why it's safe to assume this would occur in places not getting a lot of immigrants.

I could see a general movement to the Free Column starting in the 1880s, sure. I've often said I suspect Slavery would've died out in the United States somewhere between 1890-1910/1920 because of changing economic conditions and international outlooks. By that point, however, you're unlikely to get a civil war because that's no longer in the interest of Southerners to resist this movement.I emphasize that Missouri, Maryland, and Delaware - states which did receive immigration - probably would shift into the free column over time. Most likely in the 1870s or 1880s.

Here's one aspect that could change everything in our viewpoints: the Boll Weevil entered the United States from Mexico in the 1890s. It's entirely possible with the changed border it could enter far sooner than historical...

Jackson Lennock

Well-known member

So? Why would a bigger Mexican cession delay the admission of California? California's admission was rushed because of a fear that the Californians would go it alone. That's not any less true here.The Mexican Cession was in 1848, California did not enter the Union until 1850. Likewise, the proposal to split off Southern California to form a new state was from the late 1850s, so California's admission isn't a set deal and could certainly be changed later. As for "Colorado", the area was largely settled by Southerners and was extremely Pro-Southern in feeling, as evidenced by the fact Pro-Confederate militias were raised during the Civil War and had to be dispersed by units raised from Northern California.

Proto Industrial activities, such as mining, did generally have the same rates of return as Cotton on average. The 1850s Boom in Cotton was an anomaly that produced distortions; the South actually lost industry over the course of that decade because of this.

They also lost industry because planters were opposed to industrialization due to a recognition of the political threat the emergence of an industrial class and free laborers would pose. Efforts at setting up steel development in Birmingham were blocked in the 1850s by local politicos, for example.

For one, the fact the national environment that provoked said court cases is completely different. They did not appear from the ether, but were instead an end result of escalating sectional tensions engendered by the conflict over limited space/land. Without the dissolution of the Whigs and the rise of the Free Soil Republicans, the Southern Moderate faction will still be around and powerful.

People are still going to bring lawsuits, and the Supreme Court still was mandated to hear appeals at the time. The cases are going to get to the Supreme Court.

The Whigs are going to dissolve eventually because popular opinion is going to force a split.

Indeed it failed, and it's obvious to see why; the extension of the 1820 Compromise Line would have allowed the addition of three Slave States (New Mexico, Arizona and SoCal/"Colorado") while allowing for about 15 Free States. It would've completely ended the prospect of Balance in the Senate upon which the South was depending upon, as exemplified in how the Senate was used to check the Wilmot Proviso. The rumbling to oppose Slavery was on Free Soil principles; Northerners were not abolitionists at this time, but were opposed to competition with Slave labor in the Great Plains.

Except even extending the Missouri Compromise line to the pacific was a bridge too far for northerners. It wasn't *just* the issue of the plains that motivated the north.

You seem to be of the opinion that the reason the extension failed was because of southerners not getting enough states? That doesn't make sense. The Wilmot proviso passing the house and the compromise line failing shows that much of the reasons was to do with not wanting *any* expansion of slavery.

If three additional slave states was too much for the north to tolerate, why would an even *greater* number of slave states be tolerated?

Because their catalysts are removed. Even after the bitter political conflict of the 1850s, including Bleeding Kanasas, it took four years of war and hundreds of thousands of dead to push the nation in favor of Abolitionism and even then, this was a strong struggle in 1865. Outside of Slavery, I can think of no other pressing political conflict of the day that could invoke such a split. Tariffs usually get invoked in Lost Cause mythology, but the Whig Party had a strong Southern following that was also Pro Tariff.

There's a difference between "end it in the south" abolitionism and "containment" abolitionism though. It took the Civil War to pass the Thirteenth Amendment. But the general idea of opposing an *expansion* of slavery was present decades sooner. It was major reason why there was so much opposition to the Texas annexation and the Mexican War to begin with. Without those things, Slavery was contained and condemned to death in the South as the soils got used up.

Given nominating conventions were controlled by the parties themselves at this time, rather than popular vote, I don't see that as an issue. Likewise, it becomes less of an issue if the South has maintained parity in the Senate. Part of the concern with Lincoln was the expectation all remaining territories would go Free, which would tilt the balance against the South.

Delegates to conventions were allocated by state population. Northern factions of parties will have more people.

Actually, it talked about Kentucky and Delaware:

"Yet without the Civil War, it seems highly unlikely that the states of the border South would have acted to abolish slavery anytime soon. Antislavery forces were growing weaker, not stronger, in the region at midcentury. In 1851 Cassius Clay, a gradualist, lost his bid for the governorship of Kentucky by an overwhelming margin. "Even in Delaware," Freehling acknowledged, 'where over fifteen thousand slaves in 1790 had shrunk to under two thousand in 1860, slaveholders resisted final emancipation"--and they did so successfully until 1865. Perhaps most revealing of all was President Lincoln's failure to persuade border South congressmen to support gradual, compensated emancipation. Had the United States followed the Brazilian path to abolition, the South's peculiar institution would almost surely have persisted beyond 1900."

An additional 18 years of immigration and development failed to break Planter power in Delaware, so I'm not sure why it's safe to assume this would occur in places not getting a lot of immigrants.

I should have been cleared: my point was that Delaware in the coming decades would see a change because the planters were barely hanging on as things stood.

And I focused on Maryland and Missouri, states with burgeoning industrial cities that got a heck of a lot more immigrants than Kentucky did.

I could see a general movement to the Free Column starting in the 1880s, sure. I've often said I suspect Slavery would've died out in the United States somewhere between 1890-1910/1920 because of changing economic conditions and international outlooks. By that point, however, you're unlikely to get a civil war because that's no longer in the interest of Southerners to resist this movement.

Here's one aspect that could change everything in our viewpoints: the Boll Weevil entered the United States from Mexico in the 1890s. It's entirely possible with the changed border it could enter far sooner than historical...

Okay.

First, Southern elites (who are the only people who really matter in southern politics, to be frank) weren't exactly the most economic in their thinking. They had a whole silly ideology about their own nobility which they convinced themselves of. Even if the economic conditions change, they're not going to tolerate a big change to the social order. The boll weevil could undermine the profitability of cotton, but that's not the same as the planters being willing to give up slavery without kicking and screaming.

The southern racial hierarchy was an economic system, but it was also a social system with a huge amount of psychological investment.

As a separate matter, white sharecropping first emerged in the south prior to the Civil War in parts of Mississippi and Tennessee. The trend in the antebellum period was further consolidation of who owned slaves in the south and of land ownership. Even separate from slavery, the semi-feudal hierarchy was getting even more entrenched, not less.

James Henry Hammond, a member of the Senate, made the Mud Sill speech. Alexander Stephens made the Cornerstone Speech. The ideas of southern political society were deeply entrenched and feudal and they aren't going away.

Whites also were increasingly conscripted into slave patrols down south, which fostered some resentment.

If anything, the stubbornness of the planters, the economic hit the planters would face because of the Boll Weevil, the gradual growth of the sharecropping system seem, and outside pressures by northern antislavery agitators seem likely to foster some sort of uprising among the yeomen against the planters over time. Just think of the Dorr Rebellion from 1842 in Rhode Island.

Last edited:

- Location

- NYC (né Falkirk)

- Pronouns

- he/him

The idea that the controversies that came before, during and after the OTL Mexican-American War with regard to domestic US politics can be waved away with more territory taken from Mexico is, to say the least and perhaps even charitably, naïve.

Jackson Lennock

Well-known member

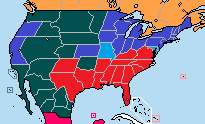

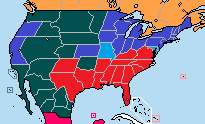

A possible map as of 1870. Red is a Slave State, Blue is a Free State, and Light Blue is a state which flipped from Slave to Free by 1870. I assumed the border would go from Tampico west to the border of San Luis Potosi. The border followed the western border of San Luis Potosi to the Tropic of Cancer, and from there went straight to the Pacific.

Here, the Compromise of 1850 sees a second state carved out of Texas. The 36-30 line is extended to the Colorado River. Lands south of the line are allocated to popular sovereignty. In a sense, the north is coming out more ahead than OTL (since popular sovereignty is not applied to the areas the North most wanted), but the South isn't much worse politically than historically, since they have more room for slavery to expand into south of 36-30 than extending the line OTL would have granted them.

Free States: 19

Flipped Free States: 3

Slave States: 14

Here, the Compromise of 1850 sees a second state carved out of Texas. The 36-30 line is extended to the Colorado River. Lands south of the line are allocated to popular sovereignty. In a sense, the north is coming out more ahead than OTL (since popular sovereignty is not applied to the areas the North most wanted), but the South isn't much worse politically than historically, since they have more room for slavery to expand into south of 36-30 than extending the line OTL would have granted them.

Free States: 19

Flipped Free States: 3

Slave States: 14

- Location

- Over the rainbow

While not disagreeing with most of what you've noted, this has the Birmingham situation backwards. Planters were among the coalition pushing for development of the Birmingham site in the 1850s. It was killed off by small-farmer opposition, not planters. And their opposition was mostly rooted in "don't use our tax money to support private interests" rather than anti-industrialisation per se.They also lost industry because planters were opposed to industrialization due to a recognition of the political threat the emergence of an industrial class and free laborers would pose. Efforts at setting up steel development in Birmingham were blocked in the 1850s by local politicos, for example.

In general, some planters were opposed to industrialisation on principle, while others were willing to contemplate it in some circumstances, particularly when the cotton price dropped. More planters spoke in favour of industrialisation during the 1830s/early 1840s cotton price crash, for instance. It's hard to judge exact percentages, but certainly planters weren't monolithically opposed to industrialisation.

While not disagreeing with most of what you've noted, this has the Birmingham situation backwards. Planters were among the coalition pushing for development of the Birmingham site in the 1850s. It was killed off by small-farmer opposition, not planters. And their opposition was mostly rooted in "don't use our tax money to support private interests" rather than anti-industrialisation per se.

In general, some planters were opposed to industrialisation on principle, while others were willing to contemplate it in some circumstances, particularly when the cotton price dropped. More planters spoke in favour of industrialisation during the 1830s/early 1840s cotton price crash, for instance. It's hard to judge exact percentages, but certainly planters weren't monolithically opposed to industrialisation.

This is also rooted in the assumption that slavery was doomed with soil exhaustion and I'm not sure this is the case. Baltimore and Richmond seem to be pretty good evidence that you could have urbanized and industrialized slave societies in the south, although the character of those societies was quite different from the planterocracy in the agrarian areas of the south-more free blacks, more "mixed-status" relationships, more skilled and in some cases literate slaves, etc.

Note that this observation raises important questions about why planters assumed that slavery containment doomed their institution and their power, instead of simply writing it off as a fifty years from now problem or plotting a transition away from soil-wrecking cash cropping that would let them keep slavery and their power intact.

Jackson Lennock

Well-known member

Thank you for the correction.While not disagreeing with most of what you've noted, this has the Birmingham situation backwards. Planters were among the coalition pushing for development of the Birmingham site in the 1850s. It was killed off by small-farmer opposition, not planters. And their opposition was mostly rooted in "don't use our tax money to support private interests" rather than anti-industrialisation per se.

In general, some planters were opposed to industrialisation on principle, while others were willing to contemplate it in some circumstances, particularly when the cotton price dropped. More planters spoke in favour of industrialisation during the 1830s/early 1840s cotton price crash, for instance. It's hard to judge exact percentages, but certainly planters weren't monolithically opposed to industrialisation.

History Learner

Well-known member

So? Why would a bigger Mexican cession delay the admission of California? California's admission was rushed because of a fear that the Californians would go it alone. That's not any less true here.

Point being that the admission of California on OTL terms was not set in stone, and was actively under consideration for a change as late as 1859 with the Colorado proposal.

They also lost industry because planters were opposed to industrialization due to a recognition of the political threat the emergence of an industrial class and free laborers would pose. Efforts at setting up steel development in Birmingham were blocked in the 1850s by local politicos, for example.

Actually, the Planters were not opposed to industrialization; this is a common misconception born of the "State's Rights" defense invented Post War. Modernizing a Slave Economy: The Economic Vision of the Confederate Nation by John Majewski makes this point well:

States’ rights ideology, though, eventually lost to a more expansive vision of the Confederate central state. As Table 6 shows, the Confederate government chartered and subsidized four important lines to improve the movement of troops and supplies. Loans and appropriations for these lines amounted to almost $3.5 million, a significant sum given that a severe shortage of iron and other supplies necessarily limited southern railroad building. Jefferson Davis, who strongly backed these national projects, argued that military necessity rather than commercial ambition motivated national investment in these lines. The constitutional prohibition of funding internal improvements ‘‘for commercial purposes’’ was thus irrelevant. That Davis took this position during the Civil War followed naturally from his position on national railroads in the antebellum era. Like Wigfall, he believed that military necessity justified national railroad investment. As a U.S. senator, Davis told his colleagues in 1859 that a Pacific railroad ‘‘is to be absolutely necessary in time of war, and hence within the Constitutional power of the General Government.’’ Davis was more right than he realized. When the Republican-controlled Congress heavily subsidized the nation’s first transcontinental railroad in 1862, military considerations constituted a key justification. Even after the Civil War, the military considered the transcontinental railroad as an essential tool for subjugating the Sioux and other Native Americans resisting western settlement.

When the Confederate Congress endorsed Davis’s position on railroads, outraged supporters of states’ rights strongly objected. Their petition against national railroads—inserted into the official record of the Confederate Congress—argued that the railroads in question might well have military value, ‘‘but the same may be said of any other road within our limits, great or small.’’ The constitutional prohibition against national internal improvements, the petition recognized, was essentially worthless if the ‘‘military value’’ argument carried the day. Essentially giving the Confederate government a means of avoiding almost any constitutional restrictions, the ‘‘military value’’ doctrine threatened to become the Confederacy’s version of the ‘‘general welfare’’ clause that had done so much to justify the growth of government in the old Union. The elastic nature of ‘‘military value,’’ however, hardly bothered the vast majority of representatives in the Confederate Congress. The bills for the railroad lines passed overwhelmingly in 1862 and 1863. As political scientist Richard Franklin Bensel has argued, the constitutional limitations on the Confederate central government ‘‘turned out to be little more than cosmetic adornments.’’

The Supreme Court is not required to hear them and, without the inflamed sectional tendencies working against moderation, will be operating under much less pressure to lean one way of the other. Dredd Scott could have a much more limited ruling, presuming it still appears before the Supreme Court.People are still going to bring lawsuits, and the Supreme Court still was mandated to hear appeals at the time. The cases are going to get to the Supreme Court.

The Whigs are going to dissolve eventually because popular opinion is going to force a split.

Besides Slavery, there was no other issue that presented the prospect of dividing the Whigs. If Slavery is settled, the Whigs will stay around.

Except even extending the Missouri Compromise line to the pacific was a bridge too far for northerners. It wasn't *just* the issue of the plains that motivated the north.

And yet, they were willing to sign onto the Compromise of 1850 and enough Northerners signed onto the later Popular Sovereignty concept to get it passed. California Gold fields and Plains are still theirs here, which was the focus of the Free Soil Movement, besides excluding Slavery from their own States.

You seem to be of the opinion that the reason the extension failed was because of southerners not getting enough states? That doesn't make sense. The Wilmot proviso passing the house and the compromise line failing shows that much of the reasons was to do with not wanting *any* expansion of slavery.

It was a large factor, especially when you look at who was voting for what with the Compromise Line vote.

If three additional slave states was too much for the north to tolerate, why would an even *greater* number of slave states be tolerated?

Because they would be matched, on a 1:1 basis, with Free States, as had been the case since the Missouri Compromise. A lot of the panic from both sides in the 1850s was a result of fearing the other was about to solidify their dominance within the Union.

There's a difference between "end it in the south" abolitionism and "containment" abolitionism though. It took the Civil War to pass the Thirteenth Amendment. But the general idea of opposing an *expansion* of slavery was present decades sooner. It was major reason why there was so much opposition to the Texas annexation and the Mexican War to begin with. Without those things, Slavery was contained and condemned to death in the South as the soils got used up.

It was present, but remained very much a minority position. How else could the 1850 and 1854 Compromises have occurred, given Northern dominance of the House?

Delegates to conventions were allocated by state population. Northern factions of parties will have more people.

They will also be Party men, seeking to keep the party and thus their power intact.

I should have been cleared: my point was that Delaware in the coming decades would see a change because the planters were barely hanging on as things stood.

I see that as questionable, given Delaware was one of the last holdouts to abolish Slavery even after the bloodiest war in American history galvanized opinion in favor of Abolitionism.

And I focused on Maryland and Missouri, states with burgeoning industrial cities that got a heck of a lot more immigrants than Kentucky did.

Equally so, the underlying trends were still not conducive to such movements. There is no inherent contradiction between industrialism and Slave holding

I'd recommend, besides Majewski, reading Colossal Ambitions: Confederate Planning for a Post–Civil War World by Adrian Brettle. The Southern political elite dreamed of constructing an industrial empire, and during the war engaged in a fair bit of what we would call State Capitalism to help achieve that. Little know fact is that in the 1840s, something like a third to 40% of American iron output was from the Upper South and mostly from Slave labor; the Cotton boom ended that because it became more profitable to switch "labor" into cash crop production.Okay.

First, Southern elites (who are the only people who really matter in southern politics, to be frank) weren't exactly the most economic in their thinking. They had a whole silly ideology about their own nobility which they convinced themselves of. Even if the economic conditions change, they're not going to tolerate a big change to the social order. The boll weevil could undermine the profitability of cotton, but that's not the same as the planters being willing to give up slavery without kicking and screaming.

In other words, they were well aware of and did respond to trends in economics, nor were they opposed to industrialization in of itself. Once it becomes clear that's the economically most beneficial path, they'll go to that and once the costs of maintaining slavery are too much, they'll end it in favor of Jim Crow. We don't really have to speculate on what a Post-Slavery social order in the South will look like because the violence of the 1890s and institution of Jim Crow Laws showed exactly what, why and how they would institute such a replacement system.

Yes, I can see such political tensions eventually contributing to the end of Slavery in the South. However, that further precludes the Civil War, because at that point, whom is left to fight it for the Planters? Slavery was ultimately untenable, both on moral and economic grounds, but that it required a civil war to end it is something I'm not convinced of.As a separate matter, white sharecropping first emerged in the south prior to the Civil War in parts of Mississippi and Tennessee. The trend in the antebellum period was further consolidation of who owned slaves in the south and of land ownership. Even separate from slavery, the semi-feudal hierarchy was getting even more entrenched, not less.

James Henry Hammond, a member of the Senate, made the Mud Sill speech. Alexander Stephens made the Cornerstone Speech. The ideas of southern political society were deeply entrenched and feudal and they aren't going away.

Whites also were increasingly conscripted into slave patrols down south, which fostered some resentment.

If anything, the stubbornness of the planters, the economic hit the planters would face because of the Boll Weevil, the gradual growth of the sharecropping system seem, and outside pressures by northern antislavery agitators seem likely to foster some sort of uprising among the yeomen against the planters over time. Just think of the Dorr Rebellion from 1842 in Rhode Island.

Let's say the Boll Weevil comes in sometime in the 1870s, and ruins the Cotton fields. Most Planters will begin switching over to Factory work for their Slaves while leasing their ex-fields to Yeoman farmers, on the Sharecropper basis. By the 1890s, resentments over the ownership of land, the economic advantages of free labor and international pressure will start to really make themselves felt, I suspect.

fluttersky

Well-known member

- Pronouns

- they/any

On the civil war topic I think there are too many uncertain factors, and that the simple answer is that it's possible but not guaranteed that things would go similarly to in reality.

America tended to annex pretty large states in the west and I don't see why that trend wouldn't continue– could see a new State of Leon/State of New Leon covering Nuevo Leon, Coahuila, and Tamaulipas and with its capital in Monterey (presumably a new slave state admitted once a decent number of American settlers arrive), and Chihuahua becomes a state later (probably including Sonora except that the northwestern corner of Sonora ends up in Arizona). The California division does seem feasible given Baja California's inclusion in the hypothetical Colorado too. So if all else is much the same, I guess America would end up with 53 states by the present day?

America tended to annex pretty large states in the west and I don't see why that trend wouldn't continue– could see a new State of Leon/State of New Leon covering Nuevo Leon, Coahuila, and Tamaulipas and with its capital in Monterey (presumably a new slave state admitted once a decent number of American settlers arrive), and Chihuahua becomes a state later (probably including Sonora except that the northwestern corner of Sonora ends up in Arizona). The California division does seem feasible given Baja California's inclusion in the hypothetical Colorado too. So if all else is much the same, I guess America would end up with 53 states by the present day?