Chapter Two – New Nazis

The New Nazis depicted the German Farmer as the Blueprint for the 'National Community.'

The New Nazis depicted the German Farmer as the Blueprint for the 'National Community.'

Herr der Rassen – ‘The Lord of the Races’ – is a two-volume tome mostly written during Scheubner-Richter’s stay in Landsberg. Rudolf Hess, his fellow inmate was his editor and sole critic. A meandering screed, part-adventure novel, part-autobiography. Scheubner-Richter’s first novel Homecoming (1918) [1] detailed the Leutnant’s experiences in the Baltic during the Russian Civil War. This second book focused on his experiences during the Armenian Genocide.

‘In the deserts of Turkeyland I brooded on the nature of world politics. As Nietzsche teaches us, the superman is forged from suffering, and nowhere in the world suffered as did Turkey during the Great World War. Like a Japanese monk in his mountain garden, among the blue rocks of Erzemum, I, Scheubner-Richter, received enlightenment.’

The book was influenced by the apocalyptic writings of White Russian exile Piotr Krasnov whose novels featured a stalwart protagonist discovering devious Jewish plots to destroy western civilization. The novel follows the exploits of Scheubner-Richter and his adjutant Paul Leverkuehn as they journey to Erzemum. The narrative grows progressively bleaker as Scheubner-Richter witnesses appalling atrocities meted out by the Turkish to Armenian civilians.

Though Scheubner-Richter considered the Turkish to be among the lowest races, exceeded in backwardness and impurity only by the Jews, there was a perverse respect for the ruthlessness with which the Turks murdered their countrymen. The Leutnant came to view the Armenian Genocide as a blueprint for future campaigns of ethnic cleansing.

‘One may admire the singular drive of the Turk to remove alien elements from within his borders. If we undertook such disciplined action to remove the traitors that despoil Germany then our nation would arise from its prostrate position and again dominate the world.’

His use of the term ‘traitors’ here is telling. In his writings Jews were elided with the traitorous Marxist dogma which had supposedly cost Germany the war. And since Communism inevitably lead to destruction all Jews would have to be removed for the sake of the race’s survival. Scheubner-Richter, once the stalwart defender of the Armenians, heaps scorn upon ‘those dusky nomadic Hittite-Syriac-Babylonian mongrels called the Hebrews.’

Scheubner-Richter claimed to have ‘discovered the terrible truth of the enemies’ master-plan.’ Miscegenation was, he claimed, supported by Jewish puppetmasters in Moscow and London, who wanted to weaken the Germanic races by interbreeding them with weaker groups, so that they could rule over the ashes of the world.

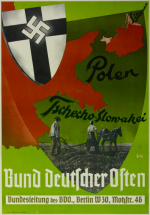

Races needed to be kept separate with the weaker peoples like the Armenians ‘shepherded’ by martial races such as the Germans and protected from the wiles of ‘aggressive races such as the Jews and Romani.’ In order to ensure the martial races were strong enough to protect the weaker races they would require living-space (lebensraum). Growing out of anxieties about German agriculture not being able to support its population growth the policy of Lebensraum called for the settlement of colonists on farmland in the east seized from ‘unnatural states’ – Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Poland, and the USSR.

‘Thus, it will be necessary to split these unnatural states into smaller reservations for their component nationalities under the protection of a benevolent class of German soldier-peasants who will govern them with the assistance of local tribal leaders. The natives will work the land, gaining an appreciation of hard-work, whilst the settler’s farms are provided with free labour. These landholders will bring peace, stability, and order to these territories whilst providing the Fatherland with a vast agricultural yield and security from foreign threats.’

The book concludes that in order for this grand plan to ‘liberate’ the subject peoples of the Eastern Unnatural States and secure agricultural land to succeed, Germany would need to rearm her military, unite economically and militarily all Germanic peoples, end reparations payments to the Allies, and ‘chase the traitorous enemy from our land forever.’

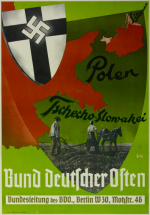

NSDAP propaganda poster celebrating the seizure of lebensraum.

Though there are many similarities between Hitler and Scheubner-Richter it is worth taking this opportunity to note the distinct differences between their political visions since they became most marked during the period in which he wrote Herr der Rassen. Scheubner-Richter was infinitely more appealing to the German establishment than his rabble-rousing protege. Not much of a public speaker but a first rate organiser and strategist, a well-spoken patrician, respected in the upper and middle class circles he moved in. Informed by his experiences during the Russian Revolutions he disliked the use of the mob in politics which was a driving force behind his conflict with Gregor Strasser’s Black Front.

Hitler seems to have had a very dim view of Slavs perhaps cultivated during his years in Vienna. Scheubner-Richter by contrast, believed that ‘if properly educated and refined the Slavic races could be thoroughly Germanized and welcomed into our nation.’ Many of the Nazi Party’s major financiers, as late as 1929, were Russian emigres such as the Tsarist pretender Duke Vladimir Kirrilovich and his German-born wife Victoria Feodorovna. He also lacked Hitler’s class politics, seeking a legalistic way to power, rather than violent revolution. Scheubner-Richter had a deep respect for the Monarchy and the Church regarding both as central pillars upon which the new Germany must be built.

Whilst Scheubner-Richter was busy assembling his opus he simultaneously engaged in a furious campaign of letter writing. In his nine months of imprisonment he sent no less than six hundred letters to Nazi functionaries across the country helping to further cement his position as the leading light of the National Socialist movement. By the end of his sentence many party members had taken to referring to him as the ‘Führer-in-waiting.’

Prison officials sympathetic to his ideology ensured he wanted for nothing. When he wasn’t writing Scheubner-Richter was reading. His favourites were newspapers from Britain, France, and Italy, alongside escapist novels set in the medieval period. A veritable flood of well-wishers visited him at all hours. Thirty people visited the inmates for Oktoberfest on September 16th, 1924. Together they grilled sausages, drank beer, and sang songs long into the night.

Otto Leybold, the Warden of Landsberg, wrote in a memorandum on Scheubner-Richter, ‘the perfect gentleman, quiet, thoughtful, conscientious, especially towards the guards.’ Franz Gürtner, the Bavarian Minister of Justice, was much impressed by Leybold’s letters and arranged parole for Scheubner-Richter, Hess, and Weber. On December 21st 1924, Max von Scheubner-Richter walked out of Landsberg Prison and back onto the political stage.

Despite his fame and the loyalty of his fellow inmates in Landsberg Scheubner-Richter’s control over the party was far from absolute. Outside the prison gates, in the absence of a powerful leader, the Nazi Party had split into factions centred on different regions. In the north-west, Gregor Strasser and Joseph Goebbels lead the Populist group (National Socialist Freedom Movement) which called for a more radical redistributive economic policy and closer ties with the Soviet Union. In the south, a former chicken farmer named Heinrich Himmler headed a conservative group, the True National Socialists (Greater German Conservative Party), which supported a return to Hitler’s ideals.

Julius Streicher had attempted to form his own group, the Greater German Peoples’ Community (GVG), alongside Alfred Rosenberg. The party newspaper The Stormer (Der Stürmer) sold well among the working-class. It spoke in simple terms people could understand, titillating them with tales of sexual depravity allegedly committed by Jews, tugged at their heart-strings with sob stories of widows losing their houses to greedy Jewish landlords. But Streicher was unable to transform this readership into a mass movement. Streicher was a man of phenomenal ability, a top-rate communicator and writer capable of whipping up the masses. But his fatal flaw proved to be his acerbic personality, he was too cold, too personally alien, to cultivate the relationships needed to build a successful political party.

Hermann Goering returned in mid-1925 and was elected to the Munich legislature as an independent nationalist. Goering’s personal hatred of Scheubner-Richter prevented him from re-joining the resurgent Nazi Party. After the abysmal failure of his attempt to take control of the DNVP Goering formed a small but influential paramilitary organisation called The Grenade (Der Granate). Ideologically it embraced a form of extreme conservatism which opposed the revolutionary nature of fascism. It’s party anthem boldly declared, ‘your doom shall come soon all you worker scum.’

Der Granate Party Flag.

Naturally the fanatically Anti-Soviet Scheubner-Richter was appalled by the Russophile stance of the Populists. The Populists’ leadership were similarly uninterested in reconciliation, Gregor Strasser publicly denounced the ‘reactionary capitalist Scheubner-Richter’ whilst Joseph Goebbels was particularly unimpressed by the Leutnant writing, ‘What a mild and watery man, this Russian Richter, he is surely no Führer!’ [4]

At the Bamberg conference on February 14th, 1926 events came to a head. Gregor Strasser put forth a motion to support a Social Democratic bill in the Reichstag regarding expropriating estates belonging to the deposed royal family. Scheubner-Richter counted many members of the royal houses of Germany as friends and, more importantly, financial backers of his revived Nazi movement. The Leutnant took to the floor of the conference and fiercely denounced the ‘Crypto-Marxist’ Populist clique.

‘I will not have this party, which represents the only hope for Germany, carried into power on the backs of grumbling steelworkers!’ He famously declared. In response, Goebbels and Strasser alongside twenty Populist delegates walked out, forming their own party, the Revolutionary Proletarian League of National Socialists, better known as the Black Front. [5]

In March, Scheubner-Richter was elected Chairman of the NSDAP. By autumn 1926 the man of blood was master of the Nazi Party. To cement this position his old friend Alfred Rosenburg was appointed Party Secretary with control over the membership list. The various Nazi regional branches were organised into Gaus under the control of a Gauleiter. Himmler’s True Nazi faction were neutralised when Scheubner-Richter appointed him Gauleiter of Munich. Anti-Scheubner-Richter members were expelled en-masse.

In lieu of the title Führer, which only the inspired Hitler could hold his followers addressed Scheubner-Richter as ‘Leutnant’ recalling his humble rank in the Imperial German Army. In-order to sanctify Hitler’s memory, Scheubner-Richter had him declared ‘Eternal Führer of the Party’ at a meeting of Beer Hall Putsch veterans on November 6, 1926. Once he had the party firmly in hand Scheubner-Richter would spend the next four years disseminating his ten point program to various cells across the country.

A rhetorical tool and pseudo-theory which would guide the Nazi state in years to come, its ten point program was – the unification of all German communities under one state, the end of urban and rural poverty, seizure of lebensraum from the unnatural states of the east for the sustenance of the people, support for a healthy middle class through the abolition of trusts and warehouses, expansion of retirement pension and the right to an untroubled old age, protection of women and girls from sexual depravity through the death sentence for Homosexuals and other deviants, strengthening the national military, stripping of Jews and other non-Germans’ citizenship, an immediate ban on immigration from alien nations, and for agriculture to be made prosperous through the abolition of land seizures and land speculation. [6]

The years 1924-29 represented a low ebb in support for the Nazi Party. Gustav Stresemann introduced a new currency called the Rentenmark. The economy stabilised, unemployment fell below a million, wages increased. The Dawes Plan saw the negotiated withdrawal of foreign troops from the Ruhr, a staggered series of reparations that was more manageable, and massive American investment in the German economy primarily through Wall Street bonds. Welfare systems funded by American loans became the envy of the world. Unemployment fell to below 600,000 in 1928. Support for extremist parties faded. In the face of urban renewal the Nazis turned their attention to Germany’s rural areas.

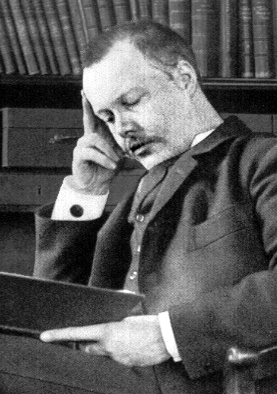

Friedrich Weber the Veterinarian Totalitarian.

As commander of Freikorps Oberland he was among the chief conspirators of the Beer Hall Putsch. Weber had considered returning to veterinary practice after his stint behind bars however Scheubner-Richter was able to convince him that he was necessary to the grand plan. Playing on Weber’s salvation complex Scheubner-Richter promised him the post of agriculture minister in the future government they would form.

On February 1st, 1925, Scheubner-Richter appointed Weber the Supreme Plenipotentiary of the Nazi Electoral Effort. Both men were painfully aware that in order to achieve electoral success they would need a broad base of support outside of Munich’s city limits. Weber’s major innovation was the so-called Northern Stratagem.

In broad terms the Northern Stratagem was a realignment of the NSDAP program to focus on rural issues. Influenced by the writings of leading party ideologue and Scheubner-Richter ally Walter Darré, Weber advocated for a ‘blood and soil’ policy, establishing Nazi branches in agricultural areas. The Nazis shifted from self-described revolutionaries to a new stance as defenders of the established order. As Weber wrote in a March 1925 letter to Scheubner-Richter. ‘The National Socialist Party must become the party of the lower-to-middle class in the rural German town.’

In the period 1926-29 the Nazis tended to excel in places which were isolated, backwards, and resistant to change. For example, Geest, their stronghold in Schleswig-Holstein, was a sandy, hilly region of family-owned farmsteads and small villages. NSDAP voters were usually middle class, artisans, ex-soldiers, clerical workers, small farmers, and shopkeepers. Among these voters there was general consensus that NSDAP were the only party willing to address their political concerns. Nazi policies promised to end farm foreclosures, increase agricultural prices, and abolish the dreaded Weimar bureaucracy.

It would be easy to imagine that economic considerations were the only reason for Nazi successes. In truth, many Nazi supporters were economically stable, even successful. The eastern portions of Schleswig-Holstein, dominated by wealthy landowners lording over large palatial estates, returned Nazi candidates at the 1928 election. [7] Middle class paranoia about expropriating leftists and degenerate modernists played a role in early support for Nazism. Older conservative voters longed for the stability of the German Empire and distrusted democracy. Second and third sons who did not stand to inherit land supported territorial expansion in hopes of gaining land grants in the east. Many rural voters were wooed by Nazi promises that they would have a key part to play in coming national community. Weber wrote of the German farmer:

‘In this sleepy folk are found the blueprint for the national community. The men are strong, hard-working, and stern. The women are obedient, fertile, and fecund. No boundaries of class or race or faith. In hard times any member of the village may lean on any other. A single community functioning as organism.’

Nazi representatives dominated elections to the Agricultural Chambers thanks to the gentry in Thuringia and Schleswig-Holstein bank-rolling local branches. Unsurprisingly, Scheubner-Richter’s sole successes in the 1928 election came from these wards. Out of 124,663 total votes almost all of these were concentrated in the NSDAP islands of Schleswig-Holstein and Thuringia. [7]

Owing to rural fears about urban outsiders the Nazis recruited local authority figures to lead the Northern Stratagem. Speakers at Nazi events were respectable establishment types, grizzled U-boat captains, university professors, wounded Great War veterans, and dashing Arctic adventurers. Christian ministers were often the first target for conversion to the cause once an office had been established in a town. In Upper Saxony the Gauleiter was a demure, bespectacled librarian. In Oberstdorf, Bavaria, the NSDAP branch was established by Dr. Alexander Helmling, a respected local physician. [8]

In his position as Gauleiter, Himmler went to great lengths to recruit leading patrician families in Munich to the cause, albeit with limited success. The Bavarian aristocracy always looked down upon this up-jumped chicken farmer. Establishment newspaper the Munich Latest News began referring to Himmler as the Farmboy (Der Bauernjunge) a nickname he would carry for the rest of his life.

In part, the success of Scheubner-Richter was in creating a politicised base of support. NSDAP members were expected to attend rallies year-round. Softly-spoken, with refined North German accent, Scheubner-Richter was an uninspiring public speaker. Ernst Hanfstaengl, his stage manager, turned this to his advantage however. It was the firebrands – Streicher, Helldorff, Himmler, and Rosenberg – that made the big speeches at party rallies. The Leutnant would appear at the end of each rally, speaking sternly and solemnly, raising his voice at the very end of the address to begin the almost liturgical recitation of the party creed: ‘That which the King (Frederick II) dreamt, the Prince (Bismarck) forged, the Führer (Hitler) defended, and the Leutnant (Scheubner-Richter) shall save! Hail Victory!’ [9]

American sociologist Wilhelm Abel described a Scheubner-Richter rally thusly: ‘Max was always a calm island in an ocean of radical fury. One-by-one, the banner-wavers would stand up and rant, then at the last, when the crowd had sweated themselves out, a hush would descend and he would appear. Speaking with that grandfatherly North German lilt. In looks and manner he reminded one of a Prussian schoolteacher, solemn and patrician, familiar yet distant.’

Northern Stratagem propaganda emphasised Scheubner-Richter’s personal piety and dedication to the Christian faith. The extent to which this professed belief was genuine is uncertain. In Landsberg the Leutnant read Luther’s On The Jews & Their Lies (1543) a tome he religiously re-read every year for the rest of his life. In speeches Scheubner-Richter often referred to himself as a soldier of Christ and stressed his personal donations to major Christian charities. It evidently slipped his mind that vanity was a deadly sin.

‘I feel the hand of the almighty upon my shoulder. He guides me in all things, gives me succour, girds my loins against enemy barbs. I am a Christian and I wish to live in a Christian nation.’ The Leutnant declared in 1927. That same year, with the support of evangelical protestant clergy, he launched the Faith Rectification campaign, a speaking tour by conservative clerics in major rural communities encouraging simple living and a return to traditional family values.

A variety of churchmen were drawn to this effort. Ranging from unassuming dupes such as Wilhelm Zoellne, an old-fashioned Lutheran superintendent, to fanatics like Ludwig Münchmeyer, a Saxon pastor who had been defrocked for his heretical beliefs. The latter was a close confidant of the Leutnant’s first wife Mathilde and later leader of the All-German Church. [10]

Nazi attempts at penetrating the urban proletariat met with less success. Gregor Strasser dispatched Joseph Goebbels to Berlin to head up the Black Front Factory Organisation in October 1926. By 1928 they had cells on the floor of all major factories in the city. Occasionally they united with communists and other radical trade unions in organising wild-cat strikes. The National Socialist Industrial Labourer’s Corps, by contrast, were less militant, less organised, less numerous. Nazi presence in Berlin was limited to the wealthy western districts of the city. Goebbels wryly noted in his diary: ‘Our street-fighters wear overalls theirs wear dinner jackets.’

Therein lay the advantage and ultimate failing of the Black Front, in their focus on street violence and wealth redistribution, they provided an outlet for poor workers’ frustrations with their bosses and the political elite. But this economic radicalism and anti-clericalism prevented them from appealing to the middle and upper classes and excluded them from the Catholic Rhineland and south. It remained a purely Prussian group concentrated in poorer areas of the Berlin-Brandenburg metropolis.

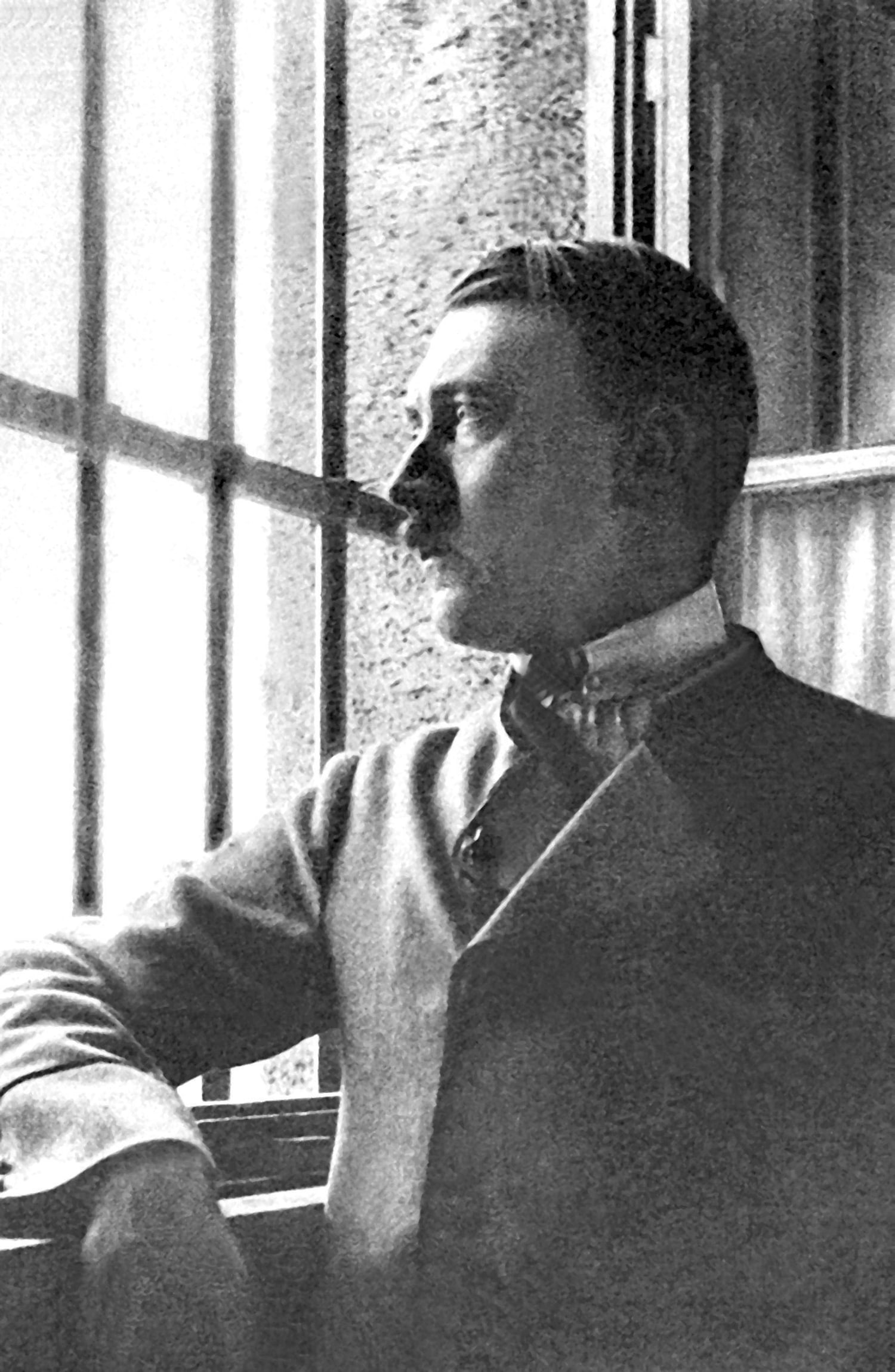

Graf von Helldorff the Man with the Heart of Iron.

Reformed and reconstituted into a major paramilitary force, many of the radical elements in the SA had defected to the Black Front’s Combat League (KG), allowing the Graf an unprecedented opportunity to purge the organisation of Anti-Scheubner-Richter thoughts. SA unit leader’s were made answerable to officers (Gruppenführer-Leibstandarte). Politically unreliable members were expelled from the organisation. The Graf made a particularly thorough effort to kick out ‘homosexuals and other troublemakers’, most notably Edmund Heines commander of the Munich SA, and a re-education program began with an eye to synchronising the political ideology of the rank-and-file. Membership grew to 250,000 by 1932 and numbered over 1.5 million by 1934. [12]

In 1927 the Graf formed the Corps of Guards (Leibstandarte) to act as an officer corps for the SA. Whilst the Stormtroopers concerned themselves with street brawls Leibstandarte presented itself as a mixture between a Freikorps unit and an old-fashioned gentleman’s club. Training centres were established, crypto officer schools, open to anyone of good Aryan stock. Courses were held in pistol and machine-gun shooting, small unit tactics, alongside horse-riding and dining etiquette. Of the 120 Leibstandarte officers in 1927, 31 were members of elite dining clubs, 12 were professors at good universities, and 40 were doctors or veterinarians.

In the SA unemployed youth found an outlet for their rage. Mounted on motorbikes or packed into trucks, middle-aged brawlers with beer guts commanded ranks of angry young men, who otherwise would have drank away their destitute youth in the doss-houses of rustic towns and small cities.

Trade unionists and other political radicals were major targets for SA raids. The hated KPD had its own paramilitary force the Alliance of Red Front-Fighters (RFB) and the two engaged in a low-level battle from 1928 to 1932. Clashes in Neukölln district, the KPD stronghold in Berlin, were exceedingly violent with over 200 injured in a single engagement on June 28th, 1929.

The pot-bellied revolutionaries reserved much fury for the traitors of the Black Front. In a ‘grand offensive’ on December 1st, 1929, gangs of SA marched through the Strasser-supporting Wedding slums, tearing down the red hammer and sword of the Black Front and raising the bronze swastika. In response the KG attacked the NSDAP office at Potsdamer Strasse, [13] smashing up the printing works, and throwing the local Gauleiter out the window.

Nazi Propaganda in this period focused its attacks on those with no social standing. The so-called Asocials – Romani, Sinti, hardened criminals, and addicts – those deemed incapable of productive work. Non-Germanic citizens of the Republic were also tempting targets. In Schleswig-Holstein the bogeyman of choice was the Danes, in Saxony the Czechs, in Silesia and East Prussia it was Poles and Russians playing on medieval hysteria of ‘Asiatic hordes from the East.’

Naturally, Jews were the major targets for abuse. Julius Streicher, in his position as Gauleiter of Franconia in northern Bavaria and editor of Der Stürmer, was the party’s major Antisemite. Constantly railing against Polish Jews and unceasing in his demands for deportation of the Gau’s entire Jewish population. Streicher whipped up wild conspiracy theories about supposed Jewish sexual slavery rings and Judea-Bolshevik plots libellously slandering major Jewish figures, and exalting its readership to ‘Hang Judah.’

The reconstituted SA took charge of the assault on Jewish cultural life. In Frankfurt and Berlin the Graf authorised military-style patrols – dubbed ‘Christian Patrols’ – of Jewish neighbourhoods to supposedly rescue German women taken as sex slaves and discourage anti-social behaviour by Jewish youths. Trucks and lorries screamed through sleepy side-streets SA men stuffed within likes sardines. Armed with clubs they forced their way into synagogues, shops, and libraries. Looting whatever they wanted, smashing up whatever was nailed down, and mercilessly beating up anyone who got in their way.

Paradoxically many Nazi Party members had Jewish friends, lovers, even family members. Franz Schechter, a former SA commander, recalled in 1951 that ‘many of my boys had Jewish girlfriends.’ None of this was seen as contradictory to the party’s stated aims. Official propaganda focused on ‘Enemies of Germany’, a handy phrase applied to Jewish leaders foreign and domestic. In an October 1927 interview with the New York Times, Scheubner-Richter elucidated the difference between individual Jews and the gargoyle of Jewish Finance.

‘Many of the Jews in this country are fine. We do not have a problem with innocent, individual Jews. We are worried about the extremists, the financiers, the ones who are causing harm. All those that bear the guilt of Germany's defeat. So our Storm-Soldiers are going into their temples, the ones hosting extremists, and stirring them up and defeating them.’

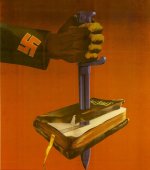

As historians we must not fall into the trap of accepting this Nazi propaganda at face value. Scheubner-Richter’s intent was always genocidal. As laid out in Herr der Rassen party policy called for the deportation of all German Jews. Furthermore Scheubner-Richter stated, in several letters that 10,000 Jews would need to be murdered with poison gas to ‘instil discipline in the survivors.’ Graf von Helldorff surmised Nazi views on the Jewish Question in a speech to party members in Franconia.

‘The European will not be safe and secure in his own home until the Jew has been expelled past the Urals into the Asiatic hinterland from whence he came.’

[1] Real book by-the-by, unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find a copy. Apparently Scheubner-Richter was a creative type (what is it with Nazis being failed artists?) and I can see him taking his down-time in prison to write a second novel.

[2] Ludendorff and Scheubner-Richter were very close, it was Scheubner-Richter who secured the old general’s support for the Beer Hall Putsch, so I think its plausible he would support the Livonian Lieutenant in a potential leadership bid.

[3] Scheubner-Richter was an aristocrat with a penchant for securing loans easily. Streicher notoriously had trouble finding print works that would print Der Stürmer. Its only natural the two would come to an arrangement. The relationship between these two men is something I’m going to cover in greater detail later, but suffice it to say that Streicher does not hold Scheubner-Richter in the same awe he did Hitler.

[4] Goebbels was only convinced to break with Strasser’s faction following a series of meetings with the very forceful Adolf Hitler. ITTL Scheubner-Richter is unable to convince Goebbels to support his position.

[5] The leading dissidents are Gregor Strasser, Otto Strasser, Joseph Goebbels, Ludolf Haase, and Franz Pfeffer von Salomon. This group goes on to form the core of the Black Front, which I’ll go into more detail on in the next chapter. Ernst Röhm is still in exile at this point.

[6] A more streamlined version of the 25-point program, most policies taken and modified from Hitler’s original proposals with the exception of point 6, which arises from Scheubner-Richter’s crackdown on ‘covert homosexuality’ in the Nazi ranks, and point 10, which emerges from Weber and Darré’s focus on rural concerns over urban ones.

[7] IOTL Geest was the NSDAP stronghold in Schleswig-Holstein but they had difficulty breaking into the more densely populated areas. ITTL Weber and Darré are more successful at winning over the upper class areas in the eastern part of the province due to their propaganda directly addressing the concerns of these communities, mostly poaching Conservsative voters from the DNVP and DVP. In all, Scheubner-Richter’s NSDAP is more successful at capturing rural votes in the Rhineland and the Catholic South than their OTL counterparts, but less successful at winning over the urban proletariat. By 1929 they are a truly rural party with all the advantages, and disadvantages, that this brings.

[8] Helmling was, in actual fact, a boorish oaf whose daughter was the local bully. IOTL he joined the party in 1934 out of naked careerism, here, he joins earlier due to the NSDAP branch in Oberstdorf having a stronger local presence.

[9] Scheubner-Richter was a poor public speaker. Not that this mattered given his role as a backroom schemer IOTL. Here, his oratorical skills are improved due to having an army of political advisors surrounding him. He’s playing to his strengths during his few public appearances by being reserved and controlled.

[10] Münchmeyer was an early supporter of Nazism. A fascinating and obscure fire-and-brimstone preacher, he ran an ‘Antisemitic Spa’ and flavoured his speeches with bible verses. He lost relevance as the NSDAP went mainstream, here, due to the Northern Stratagem and the Faith Rectification campaign, he gets to ingratiate himself with the party elite.

[11] IOTL Graf von Helldorf was one of Goebbels’s right-hand men, he served as Police Chief of Berlin, lead the charge on Kristallnacht, and later (for pragmatic reasons) helped organise the July 20 Plot. He was devious, intelligent, and utterly without principle. ITTL with Scheubner-Richter’s renewed focus on gaining rural and upper-class support for his party I think its reasonable that he’d want to appoint a Prussian, a Junker, someone with decent social standing, to head-up his new SA.

[12] OTL numbers were 400,000 in 1932 they’re lower ITTL due to more radical members getting poached by the KG.

[13] 109 Potsdamer Strasse was the Nazi HQ in Berlin until Goebbels took over as Gauleiter in 1926 and moved them to new offices in Lützowstrasse. Since Goebbels is flying the black flag ITTL the Berlin Nazis remain based at Potsdamer.