The Blancos took power in 1959 for the first time in nearly a century. The nation they were to govern was declining from its brief golden age, suffering a combination of declining exports and mounting inflation. At the same time, the state had become a sclerotic source of employment for over a quarter of the population: civil service jobs usually only required four hours of actual work per day, which enabled the motivated ones to go to another ministry after lunch and earn a second paycheck. And the state pension system was so generous that many people started drawing a pension early in their careers while still working. That is, if they could cut through the bureaucratic hurdles to get their pension - which became much smoother if they wrote to a member of the Council.

The Herrerista-Ruralista government had a solution straight from the mouths of the IMF, which involved massive cuts to the public service and the removal of the complex system of differential exchange rates for various import and export goods. But they quickly learned that their own party clients were keen for jobs and pensions, and that the coffers of the state and important firms depended on the existing trade barriers. So the state payroll actually grew under the Nationalists, while the differential exchange rates were replaced with a finely crafted system of export taxes designed to change absolutely nothing in practice.

Defeated and powerless, the Colorado elites were thrown into disarray. Waiting in the wings was Oscar Gestido, an Air Force General who had gone on to head the national airline and the state railways. His politics were obscure except for a general fiscal conservatism, but he pushed for a united Colorado front, into which List 14 became subsumed. Batlle Berres, on the other hand, made a programmatic agreement with Gestido but ran separately - but this wasn’t enough for the young Turks of the Batllista sectors, who wanted an avowedly left-wing platform. List 99 was therefore formed (otherwise the ‘People’s Government Party’) within the Partido Colorado, headed by Zelmar Michelini of the ex-Quincistas and Renan Rodriguez of the ex-Catorcistas.

These years also saw dramatic changes in the minor parties, primarily influenced by events in the rest of Latin America. Prompted by the rise of liberation theology and the more moderate Christian Democracy of the Chilean Eduardo Frei Montalva, the youth wing of the Union Civica revolted against the party leadership and transubstantiated the body into the Christian Democratic Party - the UC had hitherto been a largely conservative party, only distinctive on moral issues and religious education. The other new movement in the hemisphere was that of the Cuban Revolution - to which the Uruguayan Communist Party was more sympathetic than many other Soviet-aligned parties at the time. The PCU formed a slightly expanded coalition of puppet organisations which was called the ‘Frente Izquierda de Liberacion’, or FIDEL for short. Finally, the Herrerista Minister of Labour, Enrique Erro, split with his old party over their economic policy and position on Cuba, ultimately forming an alliance with the Socialist Party called the ‘Union Popular’.

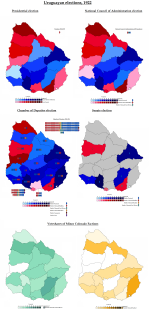

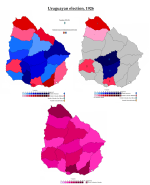

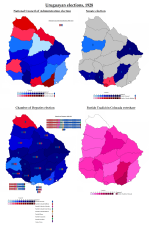

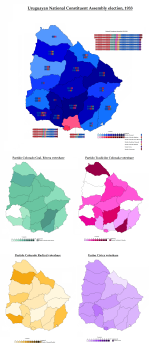

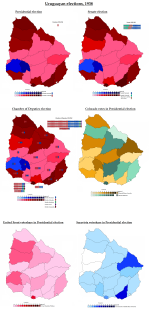

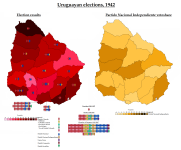

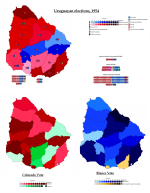

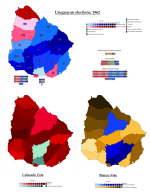

Although every minor party was running under a new name in 1962, none of them made any major advances. Neither did Gestido: although he himself was elected to the Colegiado, his united front came a poor second to the Quincistas within the Colorado lema. The real victory went to the Ubedistas, who pulled ahead of the Herrerista-Ruralista ‘Axis’ (yes, they called it that) and hauled the combined Nationalist total to 2% more than the Colorado lists.

The Union Blanca Democratica was slightly beefed up from 1958, with the addition of an ‘Orthodox Herrerista’ sector commonly known as ‘Ubedoxia’, headed by incoming Senator Eduardo Victor Haedo. Haedo had broken with the more conservative Axis because of various public statements in which he had favoured maintaining diplomatic relations with Cuba and dismissed concerns about the propaganda activity of Soviet diplomats (Uruguay was the centre of Eastern Bloc activity in South America because everywhere else kept expelling them whenever they got a US-backed dictatorship). Much later it was revealed that Haedo had been close to several Czech spies.

In any case, Haedo’s agreement with the Ubedistas was founded on a 3-3 split of the Council positions, with one of Haedo’s men agreeing to resign in favour of a mainstream Ubedista if various other terms were carried out. But the election result left the Ubedistas dependent on the Axis to be part of any solid government, so they handed over some ministerial positions to the Axis and offended the Ubedoxistas, who responded by refusing to withdraw their third Councillor. The dispute was still not settled by the date on which the Council was to be sworn in, meaning that only 5 Nationalists took their seats - a week later they reached a settlement and the fourth Ubedista was sworn in, but it was a damaging moment for the government and the whole institution of the Colegiado.

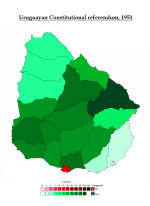

In truth, the Colegiado was holed below the waterline by this point: Herrera had already turned against it in 1956, every chairman since Nardone in 1959 had made a point of calling for constitutional reform, and now the majority sectors of each party were the Ubedistas (who had been lukewarm in 1951) and the Quincistas, who had only gone along with it out of social embarrassment. The body simply ceased to function in 1964 when a ministerial crisis combined with Council deadlock to leave every ministerial position vacant for 24 days. Finally, the last President of the Council, Alberto Heber Usher (who went on strike at one point to protest at the difficulty of getting anything done), put his money where his mouth was and announced a referendum to be held alongside the 1966 election to determine whether the winner would be a President or a new Colegiado. As both parties were able to come to an agreement, this reform passed easily, although a Communist Party proposal (which involved giving actual portfolios to each Councillor, directly electing the boards of state corporations and doing some land reform) got over 10% of the vote.

Communism was enjoying a small boom at the time, due in part to the Cuban Revolution. The Blanco governments had moved slowly on opposing Castro, particularly while Haedo had been on the Council. But in 1964, after failing to censure the Foreign Minister for making an unauthorised trade agreement with Czechoslovakia, the Council took 44 days to agree whether or not to follow the OAS in imposing sanctions on Cuba and breaking diplomatic relations. The Nationalists, particularly those of Herrerista heritage, had a tendency to favour anyone who was opposing American imperialism, no matter how left-wing. Speaking of which: at the 1962 elections, the two seats won by the Union Popular had gone to Enrique Erro and a supporter of his, much to the consternation of the Socialist Party, now out of the legislature for the first time in decades. They not only broke with Erro, but also tore themselves asunder, with a pro-Castro majority opposing a traditional social-democratic minority at the 1966 elections. And one Socialist organiser, Raul Sendic, became so disillusioned with democratic politics that he founded a left-wing militia, the Tupamaros, and began expropriating the contents of gun clubs and bank vaults.

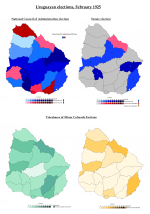

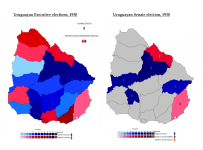

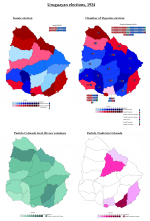

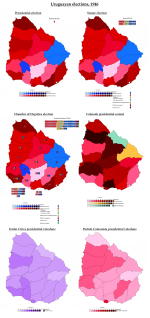

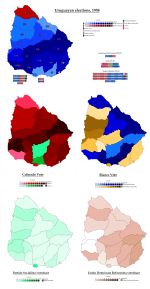

At the 1966 elections, both flavours of Socialists and the Union Popular split the vote and came out with nothing. There were also three Nationalist candidates for President (Alberto Gallinal Heber and Alberto Heber Usher were cousins and both elected for the UBD at the last election - both were beaten by the Herrerista Martin Etchegoyen) but all were unsuccessful as the Uruguayan electorate returned to normal practice and voted for the Colorado Party. But here, again, vote-splitting had its impact. Oscar Gestido, devoid of policy, won 21% of the national vote, having offered the position of Vice-President to Jorge Batlle (son of Luis Batlle Berres) and Amilcar Vasconcellos (a pro-Colegiado left-winger) and been rebuffed both times. Batlle achieved over 17% of the vote, Vasconcellos reached 6% and Zelmar Michelini won 4%. If they had all worked together against the right of the party, the history of Uruguay might have been very different.

Oscar Gestido took office on the first of March 1967 and died of a heart attack on 6 December. In the interim he went through three Cabinets: the first was broad-based but followed IMF dictates; the second turned to the left, including Michelini as Minister for Industry and Vasconcellos at Finance, but fell over the imposition of emergency powers (Prompt Measures of Security) against a general strike; the third turned well to the right, featuring Carlos Manini Rios (son of Pedro Manini Rios, the old Riverista leader) and Cesar Charlone at Finance. Charlone had last held this role under the Gabriel Terra dictatorship. It is clear that Gestido had no clue how to resolve Uruguay’s economic woes.

His successor as President did have some ideas. Jorge Pacheco Areco was a minor dynast of Colorado politics: the grandson of Jose Batlle y Ordonez’ brother-in-law. But he had inherited the editorship of the Catorcista newspaper

El Dia from his Batlle Pacheco cousins, and leveraged this to become Gestido’s Vice-President. Within a week of inheriting the position, he banned the Socialist Party and soon began to rely on periodically renewed Prompt Measures of Security. Economically, he retained Gestido’s last team and pushed further into monetarist thinking. He abolished the Wage Councils that had previously kept incomes rising with inflation and enacted wage and price freezes. Setting these prices and salaries and mediating in labour disputes was a new body, COPRIN, which had representation from both business and unions but was dominated by Executive nominees. It was relatively successful at first but over the long term it became enervating; furthermore, it discredited the Quincistas who had supported it on account of the union involvement.

No discussion of the late 1960s in Uruguay can disguise the high level of social unrest. Student protests turned violent in 1968, with police shooting teenagers and inspiring yet further protest. The Tupamaros were at their most active phase, committing high-profile acts such as taking over an entire town for a day, hijacking a radio station, kidnapping the British ambassador and organising a massive prison break, all from a base in the sewers beneath Montevideo. This all gave rise to a feeling in the military that they ought to be ready to take power for themselves if they thought it necessary - although what they would do with it was less clear. Some were unabashedly right-wing, but others were inspired by the Peruvian experience to suggest a left-wing statist government headed by the only properly organised body in the nation - the Army. The 'Peruvianists' included General Liber Seregni.

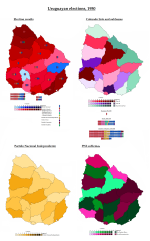

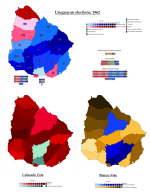

Having built support for ‘Pachequismo’, President Pacheco sought to prolong his term of office. However, Uruguay’s constitution did not permit re-election of the President, so he initiated a referendum to be held alongside the 1971 election: if it passed and his list won the election, he would be re-elected; if it failed and he still won, his Vice-Presidential nominee would take office. Within the Partido Colorado, the Pachequista slate won convincingly against Jorge Batlle’s repeat candidacy for List 15. However, the Colorados were less than 1% ahead of the Nationalists, and the lead candidate for the Blancos actually got more votes than Pacheco: this was Wilson Ferreira, who had begun as a Blanco Radical and then an Independent Nationalist, before implementing agrarian land reform under the Colegiado. He was a radical democrat and something of a populist, and his ‘Wilsonismo’ is now the main alternative tradition to Herrerismo in the Partido Nacional.

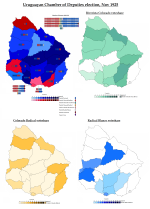

Both the Colorado and the National parties were challenged seriously for the first time in 1971 by the rise of a new alliance, the Frente Amplio (Broad Front) combining the Christian Democrats, Socialists and Communists from previous legislatures, and adding the Zelmar Michelini group of Colorados and some pro-Castro ex-Nationalists, including Enrique Erro. They kept a wall between themselves and the Tupamaros, although both Erro and Michelini had contacts with the terrorists and they stood for similar things - the Tupamaros held off from activity during the run-up to the election to give the FA a chance. However, despite running General Liber Seregni as their presidential candidate, the Frente came third and probably denied Wilson Ferreira the victory.

Name of the week: Colorado scion, Tabare Hackenbruch - named after the indigenous main character of the national poetic epic. The surname is... less indigenous