I made this in more or less a blind overnight rush after discovering the data's more readily available than I thought it was, with

a list of constituency results having been posted on Russian Wikipedia. No such thing is really available for any of the previous elections, but 1995 and 1999 both seem to have good spreadsheets available through the Wayback Machine, so they should be doable even if they end up taking slightly longer.

The 2003 legislative election was

the great realigning election of post-Soviet Russia. The previous situation had seen a relatively stable and powerful presidency, throughout the 1990s held by Boris Yeltsin and then, after Yeltsin's forced retirement following a heart and/or brain scare in 1999, by Vladimir Putin, checked by a chronically unstable State Duma dominated on the one hand by the

Communist Party and on the other by a disunited bloc of oligarchs and local independents. This situation had allowed Yeltsin and his liberal allies to push through a series of reforms privatising and deregulating the economy in the early-to-mid-90s, but then faded into complete dysfunction when it came time to figure out how to solve the myriad social problems caused by this sudden economic shock. By the time Yeltsin resigned, he and his government were almost universally despised by the Russian people (some polls put his approval rating as low as 2%).

When Putin took over the reins, he was determined to avoid repeating Yeltsin's mistakes, but more in the sense of safeguarding his own reputation and that of Moscow's political establishment than in the sense of actually addressing Russia's problems on a deeper level. He became convinced that bringing the Duma into line was key to this, and after winning the 2000 presidential election by a healthy margin, set about uniting the different "pro-administration" factions into a unified political force. The core of this new party would be the pre-existing

Unity (

Единство/Yedinstvo) party, founded in 1999 as basically a previous attempt to do the same thing, bolstered by a merger with the

Fatherland-All Russia (

Отечество-Вся Россия/Otechestvo-Vsya Rossiya) movement led by Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov and former Prime Minister Yevgeny Primakov. They were soon bolstered by a number of smaller factions, most notably the remnants of

Our Home - Russia (

Наш дом – Россия/Nash dom - Rossiya), the party of Gazprom chairman and former Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin (one of the quintessential 90s Russian oligarchs - the party was nicknamed "Nash dom - Gazprom" because it was seen as such a naked big-business vehicle), which had fallen on hard times after Chernomyrdin's dismissal as PM left it without direct institutional power. The new party was initially dubbed "Unity and Fatherland", but after its founding congress in 2001, it settled on the somewhat snappier name

United Russia (

Единая Россия/Yedinaya Rossiya).

United Russia's message was quite simple. Russia had gone through a decade of chaos and instability, with poverty, crime, corruption and border wars. Everyone was sick of change, and now, with Putin at the helm, it was time for the change to stop. There wouldn't be one more heave of neoliberal reforms to finally fix everything and bring Russia into the West, nor would the reforms be reversed and Russia returned to socialism. The current owners of the country would be kept in place, they just wouldn't rotate in power quite as often. The fact that this message resonated - because it clearly did - is... both sad and understandable. As a Windows user, I quite understand the feeling that every new change only makes things worse and that it would be nice if they could just stick with the current version, and that is sort of what Putin and United Russia promised in the 2003 State Duma election.

It was effective enough, and the local strongman network that ran much of provincial Russia was united enough, to deliver United Russia a popular voteshare of 38%, the highest of any party since the fall of the Soviet Union, and 223 seats - three off from an overall majority. For all intents and purposes, however, United Russia did win a workable majority in the new Duma, because a large portion of the independent bloc - larger than any actual party except UR itself - was elected with UR's de facto endorsement and didn't meaningfully oppose their programme in government. The same was true of the

People's Party, which had been founded by a group of independents in the previous Duma as a pro-Putin faction outside of United Russia and won 17 seats in 2003, only a handful of which were opposed by UR candidates. Several popular and/or pliable Communist deputies were given a similar treatment, as were the two remaining representatives of the theoretically left-wing

Agrarian Party of Altai governor Mikhail Lapshin. The two right-wing blocs in the new Duma - the

Liberal Democratic Party of Vladimir Zhirinovsky and the

National-Patriotic Movement "Rodina" - were both also close to the government to various degrees, and the latter in particular faced accusations of having been set up by the Kremlin to prevent nationalist voters from going to more radical or anti-government parties.

In short, the 2003 election left precious few real opposition forces in place. There was

Yabloko, a centre-left liberal party that had enjoyed some success during the Yeltsin years, but which was now reduced to just four deputies, not enough to form an official group in the Duma. In theory, there was the

Union of Rightist Forces, a coalition of neoliberal true believers left over from Yeltsin's early governments, but all three of their elected deputies left for United Russia soon after the new Duma met. The Communists and LDPR, two of the biggest factions in the new Duma, were somewhat in question, but all the other factions were pro-administration or tightly controlled opposition. And this has been the state of the Duma in every subsequent election - only a few of the names have changed.

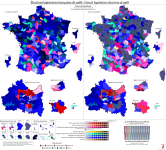

View attachment 78455