Canada 1867

Hi, I've decided to start a series of election stories and maps that you all love. I'll start with Canada, which I worked on long enough to create a DB of candidates, parties; create a map, and recreate it again. You know, it's not very nice when your opponent, who lost by a few votes, gets lost in history. The ParlInfo is incomplete, contains a lot of gaps. And while I was working on it, I learned a lot about the formation of the True North Strong and Free.

Canada was in an interesting period in history. It was the 1860s, when relations between Britain and the United States were cool. Against the backdrop of the Civil War, there was an incident involving the Trent, a ship carrying Dixie diplomats. It was a tense moment that could have escalated into war. The arena of which would have been the BNA colonies. Fortunately, it all worked out, but trade links were weakening and it was necessary to orient oneself eastwards. Next came the Grand Coalition, the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences, the dissolution of the coalition and the Macdonald government. Here also came the raids of the Fenians, who did not stabilise Canada, wanting to use it as a bargaining chip for Irish independence.

A strong political will and the complexity of the domestic situation gave birth to the state. So here we have July 1, 1867 and the British North America Act came into force. The Dominion of Canada was created by the union of Upper and Lower Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The election was to be a fait accompli, confirming the consolidation of Canada.

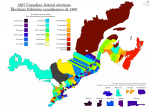

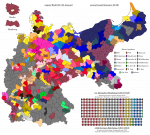

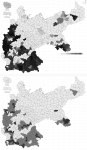

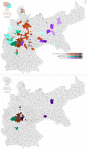

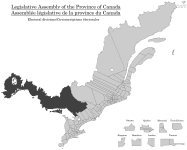

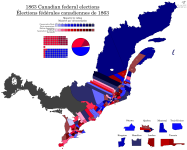

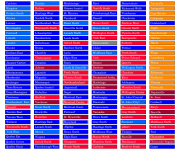

Although, in fact, these were four separate elections that bore little resemblance to the current one. Before confederation, the two Canadas were formally equal, including in parliament. They had the same number of seats - from 1854 there were 65, the same number of representatives in the cabinet and the speakers rotated through the provinces. But Upper Canada had a larger population, so the Reformers promoted 'representation by population' to their advantage. The Conservatives responded by arguing that this was aimed at creating inter-ethnic conflict and destroying the union. The debate went on for years and the problem was resolved at conferences. Ontario got 82 seats (Algoma is a worthy mention), Quebec was left with 65, of which 12 with an English-speaking majority were protected by the BNA Act and could not be taken away without residents' consent. And for the balance Nova Scotia was allocated 19 seats and New Brunswick 15 (given that Halifax and St John have two each). The 'double majority' requirement, which required the simultaneous consent of sections of Canada East and West for the bill to pass, was also eliminated.

In these provinces each riding (part or all of the county) determined the day of nomination, voting and announcement separately, so in general the elections lasted from August 26 to September 21 with the results to be determined by September 24 (for the distant Chicoutimi-Saguenay and Gaspé ridings the deadline would be extended to October 24). The Conservatives were king of the day, so they could influence where the vote would go faster or further. Otherwise, who knows if the elected candidate would go further and not have to be nominated again? In addition, the success of the Tories acted as an incentive for them to fight further.

There were not many candidates, in many places they were elected by acclamation. It was possible to run for and be elected for federal and provincial seats at the same time. As for the voting, it lasted for two days and took place by open ballot. At the end of the first day, the intermediate results were proclaimed, and from that moment on, bribery, intimidation and coercion of workers by their masters went on: everything to make the government-elected candidate win. Those who possessed censorship in several constituencies could vote multiple times. Battles over displays of emotion were not uncommon.

They were most vividly manifested in Kamouraska. Here Chapais and Pelletier were nominated in the local riding, and the former was elected acclamation in the federal one. Pelletier's admirers offered to give him the remaining seat, but Chapais was undeterred: he wanted two. At the suspiciously uncomfortable meeting, the protesters wanted the returning officer to admit responsibility for his illegal actions. He refused, and the angry mob proceeded to stone the house, take away the ballot papers, and drown the officer if he dared to choose Chapais. Two were fatally injured.

The reason for the conflict was simple: the returning officer was in close relations with Chapais and in order for him to win, he tried to disenfranchise the parishes who supported Pelletier. These statements were copies, which negated the law. And if that wasn't enough, there was a serious error in his proclamation, which had to be overturned by a second one. The officer was withdrawn and Kamouraska would elect a representative after two years. Pelletier, by the way, will win.

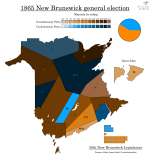

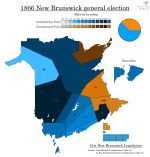

In the Maritimes, the elections were closer to the current ones. In New Brunswick, the vote was secret, lasting one day, but the polling date was still different. In Nova Scotia voting took place in one day, September 18th. This rule has existed after excessive violence was reported in the 1843 election. The first session of the parliament of united Canada has begun on November 6th, 1867.

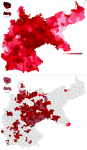

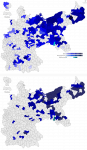

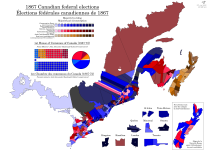

A fluid liberal-conservative coalition was built on the popularity of John A. Macdonald. In Quebec, significant support for conservatives and pro-French Bleus was provided by the Catholic Church and local elites. For instance, the Archbishop of Quebec (who died during the campaign) stated that accepting what emanated from legitimate authority is God's command, and that it is not necessary to elect fighters against the confederation. In Ontario, the Liberal-Conservative movement was a continuation of a great coalition of Tories and moderate liberals. The Confederates have developed a success in New Brunswick that began last year's provincial election, but have shown uncertainty in Nova Scotia. In addition to supporting the confederation, of course, their platform included expanding trade both within the dominion and abroad, supporting duties on industrial goods, expansion into the rest of the British colonies, increasing defense capabilities, allowing dual representation, and so on. The coalition owned an excellent organisation, election control and patronage, and picked up on the theme of Canadian patriotism.

The opposition was fragmented. The success of Ontario's Reformers in 1863 set the stage for the formation of a workable government. George Brown, while reluctantly agreeing to a coalition with the Quebec Bleus and Ontario Conservatives, realised that it was for the good of the future confederation. Of course, the Conservatives established a majority in government and some reformers became supporters of Macdonald's policies. The situation was difficult for Brown and he decided to start again. Believing there was nothing to stop the confederation, he broke the alliance with the conservatives and resuscitated the Reform movement. Then he held a convention for 700 people in Toronto in June 27th. In his speech he argued against Macdonald's government, for separation of church and state, and for maintaining relations with the United States while maintaining his own way. He, too, urged people to be vigilant and politically awareness. To earn support east of Toronto, the Reformer stronghold, he nominated in Ontario South (not the one you thought). On the first day he was leading his opponent by a slim margin. The next day, through manipulation, he lost the election. Decided he had done enough, in October he will leave Canada and politics, becoming 'the noblest victim of them all.' The Reformists have shown themselves to be weak because the theme of patriotism has divided the traditional liberal vote.

They did not have an easy time with the parties in Lower Canada. The Quebec Rouge did not accept the Grand Coalition and the anti-French Reformist position, so they were on their own. They favoured positive innovation and opposed the dominance of the Catholic Church. They also embraced confederation, which for Rouge used to seem like an excuse to anglicise Quebec. But on the whole, they went against the tide and could not count on fighting the Bleus.

In New Brunswick, party lines are confusing: in 1866 there was a choice between confederates and constitutionalists, in this election elected members were ministerialists or oppositionists, and on the floor they sat as liberals or conservatives. However, the ratio of seats occupied by Confederates and anti-Confederates was 12-3, and this was a continuation of the trend of last year's elections. Then, fearing by Fenian raids, Tilley pushed for an union with Canada.

The leader of the Nova Scotia Party, Joseph Howe, was a good orator, a courageous reformer and a ruthless opponent of the Confederation, which he saw as violent. Being loyal to the Empire, he went to England several times to prove his point. Preventing confederation was futile: the Nova Scotian parliament accepted confederation, but it was still possible to win back. During 1867 Howe conducted a political tour of the province, which was greeted with indescribable enthusiasm. Large crowds came to listen to the jibes towards Ottawa. The consequence of this campaign was that the anti-Confederates took 18 seats, the outgoing provincial PM Tupper being the only one to win among the Unionists. It was the zenith of the movement before Nova Scotia recognised the fact of confederation and Howe did not become an afterthought in supporting Macdonald.

In the long run, the Coalition won a decisive victory with 51 seats in Ontario, 46 in Quebec and 13 in the Maritimes and received just over half of all the votes. John Macdonald was the first Canadian PM to eliminate anti-Confederate sentiment domestically and pursued a skillful domestic policy. Trade, too, has returned to normal and the new railways have consolidated the country more strongly. Under his rule, the slogan 'A mari usque ad mare' would become a reality.

However, the road to confederation was not complete for everyone. In Manitoba Louis Riel showed up, becoming a Métis leader and forming a provisional government, causing discontent among some Anglophone settlers. In British Columbia the confederacy was defended by the Amor de Cosmos and the League. In Newfoundland there was a fierce battle between supporters and opponents of union with Canada. And Prince Edward Island decided not to rush into it, remaining a British dominion for a little while longer. One thing is certain - the Canadians were beginning to control their own destiny.

And of course, wish me a happy birthday!

Canada was in an interesting period in history. It was the 1860s, when relations between Britain and the United States were cool. Against the backdrop of the Civil War, there was an incident involving the Trent, a ship carrying Dixie diplomats. It was a tense moment that could have escalated into war. The arena of which would have been the BNA colonies. Fortunately, it all worked out, but trade links were weakening and it was necessary to orient oneself eastwards. Next came the Grand Coalition, the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences, the dissolution of the coalition and the Macdonald government. Here also came the raids of the Fenians, who did not stabilise Canada, wanting to use it as a bargaining chip for Irish independence.

A strong political will and the complexity of the domestic situation gave birth to the state. So here we have July 1, 1867 and the British North America Act came into force. The Dominion of Canada was created by the union of Upper and Lower Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The election was to be a fait accompli, confirming the consolidation of Canada.

Although, in fact, these were four separate elections that bore little resemblance to the current one. Before confederation, the two Canadas were formally equal, including in parliament. They had the same number of seats - from 1854 there were 65, the same number of representatives in the cabinet and the speakers rotated through the provinces. But Upper Canada had a larger population, so the Reformers promoted 'representation by population' to their advantage. The Conservatives responded by arguing that this was aimed at creating inter-ethnic conflict and destroying the union. The debate went on for years and the problem was resolved at conferences. Ontario got 82 seats (Algoma is a worthy mention), Quebec was left with 65, of which 12 with an English-speaking majority were protected by the BNA Act and could not be taken away without residents' consent. And for the balance Nova Scotia was allocated 19 seats and New Brunswick 15 (given that Halifax and St John have two each). The 'double majority' requirement, which required the simultaneous consent of sections of Canada East and West for the bill to pass, was also eliminated.

In these provinces each riding (part or all of the county) determined the day of nomination, voting and announcement separately, so in general the elections lasted from August 26 to September 21 with the results to be determined by September 24 (for the distant Chicoutimi-Saguenay and Gaspé ridings the deadline would be extended to October 24). The Conservatives were king of the day, so they could influence where the vote would go faster or further. Otherwise, who knows if the elected candidate would go further and not have to be nominated again? In addition, the success of the Tories acted as an incentive for them to fight further.

There were not many candidates, in many places they were elected by acclamation. It was possible to run for and be elected for federal and provincial seats at the same time. As for the voting, it lasted for two days and took place by open ballot. At the end of the first day, the intermediate results were proclaimed, and from that moment on, bribery, intimidation and coercion of workers by their masters went on: everything to make the government-elected candidate win. Those who possessed censorship in several constituencies could vote multiple times. Battles over displays of emotion were not uncommon.

They were most vividly manifested in Kamouraska. Here Chapais and Pelletier were nominated in the local riding, and the former was elected acclamation in the federal one. Pelletier's admirers offered to give him the remaining seat, but Chapais was undeterred: he wanted two. At the suspiciously uncomfortable meeting, the protesters wanted the returning officer to admit responsibility for his illegal actions. He refused, and the angry mob proceeded to stone the house, take away the ballot papers, and drown the officer if he dared to choose Chapais. Two were fatally injured.

The reason for the conflict was simple: the returning officer was in close relations with Chapais and in order for him to win, he tried to disenfranchise the parishes who supported Pelletier. These statements were copies, which negated the law. And if that wasn't enough, there was a serious error in his proclamation, which had to be overturned by a second one. The officer was withdrawn and Kamouraska would elect a representative after two years. Pelletier, by the way, will win.

In the Maritimes, the elections were closer to the current ones. In New Brunswick, the vote was secret, lasting one day, but the polling date was still different. In Nova Scotia voting took place in one day, September 18th. This rule has existed after excessive violence was reported in the 1843 election. The first session of the parliament of united Canada has begun on November 6th, 1867.

A fluid liberal-conservative coalition was built on the popularity of John A. Macdonald. In Quebec, significant support for conservatives and pro-French Bleus was provided by the Catholic Church and local elites. For instance, the Archbishop of Quebec (who died during the campaign) stated that accepting what emanated from legitimate authority is God's command, and that it is not necessary to elect fighters against the confederation. In Ontario, the Liberal-Conservative movement was a continuation of a great coalition of Tories and moderate liberals. The Confederates have developed a success in New Brunswick that began last year's provincial election, but have shown uncertainty in Nova Scotia. In addition to supporting the confederation, of course, their platform included expanding trade both within the dominion and abroad, supporting duties on industrial goods, expansion into the rest of the British colonies, increasing defense capabilities, allowing dual representation, and so on. The coalition owned an excellent organisation, election control and patronage, and picked up on the theme of Canadian patriotism.

The opposition was fragmented. The success of Ontario's Reformers in 1863 set the stage for the formation of a workable government. George Brown, while reluctantly agreeing to a coalition with the Quebec Bleus and Ontario Conservatives, realised that it was for the good of the future confederation. Of course, the Conservatives established a majority in government and some reformers became supporters of Macdonald's policies. The situation was difficult for Brown and he decided to start again. Believing there was nothing to stop the confederation, he broke the alliance with the conservatives and resuscitated the Reform movement. Then he held a convention for 700 people in Toronto in June 27th. In his speech he argued against Macdonald's government, for separation of church and state, and for maintaining relations with the United States while maintaining his own way. He, too, urged people to be vigilant and politically awareness. To earn support east of Toronto, the Reformer stronghold, he nominated in Ontario South (not the one you thought). On the first day he was leading his opponent by a slim margin. The next day, through manipulation, he lost the election. Decided he had done enough, in October he will leave Canada and politics, becoming 'the noblest victim of them all.' The Reformists have shown themselves to be weak because the theme of patriotism has divided the traditional liberal vote.

They did not have an easy time with the parties in Lower Canada. The Quebec Rouge did not accept the Grand Coalition and the anti-French Reformist position, so they were on their own. They favoured positive innovation and opposed the dominance of the Catholic Church. They also embraced confederation, which for Rouge used to seem like an excuse to anglicise Quebec. But on the whole, they went against the tide and could not count on fighting the Bleus.

In New Brunswick, party lines are confusing: in 1866 there was a choice between confederates and constitutionalists, in this election elected members were ministerialists or oppositionists, and on the floor they sat as liberals or conservatives. However, the ratio of seats occupied by Confederates and anti-Confederates was 12-3, and this was a continuation of the trend of last year's elections. Then, fearing by Fenian raids, Tilley pushed for an union with Canada.

The leader of the Nova Scotia Party, Joseph Howe, was a good orator, a courageous reformer and a ruthless opponent of the Confederation, which he saw as violent. Being loyal to the Empire, he went to England several times to prove his point. Preventing confederation was futile: the Nova Scotian parliament accepted confederation, but it was still possible to win back. During 1867 Howe conducted a political tour of the province, which was greeted with indescribable enthusiasm. Large crowds came to listen to the jibes towards Ottawa. The consequence of this campaign was that the anti-Confederates took 18 seats, the outgoing provincial PM Tupper being the only one to win among the Unionists. It was the zenith of the movement before Nova Scotia recognised the fact of confederation and Howe did not become an afterthought in supporting Macdonald.

In the long run, the Coalition won a decisive victory with 51 seats in Ontario, 46 in Quebec and 13 in the Maritimes and received just over half of all the votes. John Macdonald was the first Canadian PM to eliminate anti-Confederate sentiment domestically and pursued a skillful domestic policy. Trade, too, has returned to normal and the new railways have consolidated the country more strongly. Under his rule, the slogan 'A mari usque ad mare' would become a reality.

However, the road to confederation was not complete for everyone. In Manitoba Louis Riel showed up, becoming a Métis leader and forming a provisional government, causing discontent among some Anglophone settlers. In British Columbia the confederacy was defended by the Amor de Cosmos and the League. In Newfoundland there was a fierce battle between supporters and opponents of union with Canada. And Prince Edward Island decided not to rush into it, remaining a British dominion for a little while longer. One thing is certain - the Canadians were beginning to control their own destiny.

And of course, wish me a happy birthday!

Attachments

Last edited: