The 1979 Devolution Referendum

Background

The ratification of the Act of Union in 1707 between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England was not without its opponents, and since that time there have been those advocating the reinstatement of some Scottish legislature. At the time of ratification their were anti-Union riots in major Scottish cities, a generation later lingering opposition went some way to gathering the Young Pretender support in Scotland, before a century had passed the Scottish poet Rabbie Burns had decried the Scottish parliamentarians who signed the act in

Such a Parcel of Rogues in a Nation, but it would not be until the twentieth century that the people of Scotland would first get the chance to vote on some measure of devolution from London to Edinburgh.

It was during the debates on Irish home rule in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that the notion of Scottish home rule was first discussed as a serious possibility. In 1871 the Liberal Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, in a meeting held in Aberdeen stated that any measure of home rule in Ireland should also apply to Scotland. In 1912 the then Liberal MP for Dundee, Winston Churchill, in a speech in his constituency proposed devolution to Scotland and to the regions of England should Irish home rule become a reality. By the summer of 1913 a Government of Scotland Bill had passed its second reading, but did not progress any further due to the outbreak of the First World War.

After the tumultuous departure of most of Ireland and the problems of the 1920s, 1930s, and eventually the Second World War the cause of devolution took a back seat from the pressing issues of the day. Aside from the formation of the Scottish National Party in 1934 from several prior pro-independence and pro-devolution organisations, at first advocating the establishment of a devolved legislature before switching to independence in the 1940s. This change in the goals of the SNP saw the resignation of its National Secretary, John MacCormick. Instead he founded the Scottish Covenant Association, which gathered over two million signatures in favour of devolution. Despite this, the cause of devolution withered, and it again fell to the back-burner by the late 1950s.

Actions speak louder than words, and votes speak louder than signatures. In 1967, after the resignation of the former Labour MP Tom Fraser, a by-election was held in the Lanarkshire constituency of Hamilton. At the last general election in 1966, Fraser had taken 71% of the vote against his sole Conservative opponent. The SNP put forward solicitor Winnie Ewing as their candidate, its leadership instructing her to “try to come a good second in order to encourage the members”. They had not won a seat since the 1945 Motherwell election. Mrs Ewing won the seat with a majority of 1,779 votes over the Labour and Conservative candidates; she famously told a crowd after her declaration “Stop the World, Scotland wants to get on.”

Following the Hamilton by-election, itself coming after Gwynfor Evans’ breakthrough for the Welsh nationalist Plaid Cymru at the Carmarthen by-election the year before, the Labour government of Harold Wilson established the Royal Commission on the Constitution in 1969. By the time it reported in 1973 that the formation of a devolved Scottish Assembly was recommended, Ted Heath’s Conservative government was dealing with much more pressing issues of industrial disputes, the UK’s entry to the European Economic Community, and the violence in Northern Ireland; a Scottish Assembly would still not be implemented.

In the second general election of 1974, the SNP took 30% of the vote in Scotland, and Labour had one a small majority of three seats across the UK. By 1976 a series of by-election losses lost James Callaghan’s government its majority; they reached out to both the Scottish National Party and Plaid Cymru, in return for the two parties’ support in Commons votes, legislation would be instigated to allow for the devolution of political powers from Westminster to Scotland and Wales.

Scotland Act 1978

The Scotland and Wales Bill was introduced in November 1976, but the Labour Party was bitterly divided on devolution – even more so than it had been on the EEC in prior years. The Conservative Party, under their new leader, and despite still having devolution as part of their manifesto, were more concerned with opposing the Labour government than seeing through legislation to provide for something they had previously championed. Progress slowed to a crawl, and in early 1977 the government was forced to withdraw the Bill.

New bills were published in November 1977, separate ones for Scotland and Wales, but both still faced considerable opposition. The precedent for referenda had been set by the Labour government with the 1975 referendum on membership of the EEC, and when the idea was revived for the new bills on Scottish and Welsh devolution its place in British politics was confirmed. A number of Labour MPs, including Robin Cook, Edinburgh Central, were prepared to vote for the Scotland Act only on the understanding that they would be able to campaign against it in a referendum. The Leader of the House of Commons, Michael Foot, Cabinet sponsor of the Bills, agreed to this in order to bring rebellious Labour MPs in line, and with the support of the Liberals the Scotland Bill received Royal Assent on 31 July 1978. The day prior, one of the major proponents of devolution, John Mackintosh, Berwick and East Lothian, died of a brain tumour – his statue now stands outside New Parliament House in Edinburgh.

The Scotland Act 1978 proposed the establishment of a Scottish Assembly with limited legislative powers. A Scottish Executive headed by a First Secretary would take over some functions of the Secretary of State for Scotland. The Assembly would have the power to introduce primary legislation in its areas of responsibility; education, the environment, health, home affairs, legal matters, and social services. Agriculture, fisheries and food were to be shared between the Assembly and the UK government; all other matters would be reserved to the UK government, including the electricity supply.

The referendum, asking “Do you want the Provisions of the Scotland Act 1978 to be put into effect?”, would differ from the previous EEC referendum in two main respects. Firstly, a simple majority of the voters would not be enough to see the legislation put into effect. The Cunningham Amendment, after its proposer George Cunningham, Islington South, required 40% of the total electorate to vote in favour of the Assembly. This amendment incensed many on those in favour of devolution, who argued that the older the register the more out of date it was likely to be and therefore the more difficult it would be to obtain the threshold. The date of the referendum was set for 1 March 1979, to allow for the new registers due in February to be used; the extended period between the act and the referendum would also give both campaigns ample time to prepare. Secondly, where as in the EEC referendum there were two campaigns offering an obvious choice, in the devolution referendum there would be numerous bodies campaigning for either Yes or No.

Yes Campaign

The main campaign groups for the Yes vote were the Labour Movement Yes Campaign, the Scottish National Party, the Scotland Says Yes, the Alliance for an Assembly, the Liberals, and the Communists. Later groups emerged still during the campaign. This fragmentation was perhaps an inevitable result of the many distinct reasons these groups had for supporting devolution.

The Labour Movement Yes Campaign – formed from the Labour Party, the Co-operative Party, and the Scottish Trades Union Congress – saw the establishment of an Assembly as a way of answering the desire for Scots to have more say in their own affairs without going so far as to secede from the UK per the desires of the SNP. Labour used devolution as an effective platform against the SNP in three by-elections in 1978 that they might have lost otherwise – Glasgow Carscadden, Hamilton, and Berwick and East Lothian. After some thought to conducting a short campaign of General Election length, the Labour Movement instead decided to begin their campaign shortly after the Christmas and New Year holidays in 1979. Where the Labour Movement was most successful was in getting genuine support from shop stewards throughout the Confederation of Shipbuilding and Engineering Unions. The Transport and General Workers went as far as to print a full-colour broadsheet encouraging its officials at all levels to take part in the campaign. The strong Yes vote in Strathclyde owed much to the efforts of shop stewards. Though it was always debatable just how important devolution was to the Labour Party, the leadership encouraged most members to campaign for either side, with a view of it being a rehearsal for the General Election due before October of that year.

The Nationalists supported the Assembly as the first step on the road to independence, they held a special one-day conference in January to adapt their current policies for an independent Scotland to the limits of what could be achieved in the Assembly. They campaigned on what they would do if they ran the proposed Assembly, but this deflected some effort in winning support for its establishment in the first place. In some ways they were campaigning for elections to the Assembly before it was even established. This odd style of campaign may have arisen from the divided enthusiasm for the Assembly from the SNP. The gradualist wing of the Party, including George Reid, Clackmannan and East Stirlingshire, and Margo MacDonald, Depute Leader, saw the Assembly as an essential step towards independence. Others, including Gordon Wilson, Dundee East, and Douglas Henderson, East Aberdeenshire, saw any devolution as a distraction to independence and only campaigned half-heartedly. There was even a minority in the party who saw devolution as an end in itself.

The divergence between the Labour Movement and the Nationalists saw a refusal by Labour to take part in any joint campaign. Several public disagreements between the two campaigns in January led to an agreement between them that if they would not share a platform they would at least not hold conflicting platforms. This ceasefire led to both campaigns rarely campaigning in the same area on the same day when delivering leaflets, holding meetings, and canvassing. Though there was the obvious contradiction between the Labour Yes campaign campaigning that Yes would not lead to a breakup of the UK and the SNP urging a Yes vote as a means to independence, the mutual agreement not to campaign in the same area meant campaigners were never called to debate the matter between themselves. Though George Robertson, Hamilton, stating the Assembly would “kill Nationalism stone dead” still managed to incense many on the SNP campaign.

Of the smaller campaigns, Scotland Says Yes was set up by Lord Kilbrandon, who had chaired the Royal Commission on the Constitution. Though supposedly an all-party group, it had been boycotted by Labour because it contained nationalists; and its principle campaigners were Margo MacDonald and George Reid of the SNP, and Jim Sillars, Ayrshire South, leader of the Labour splinter Scottish Labour Party. Its association with nationalism convinced Alick Buchanan-Smith, Angus North and Mearns, of the Conservative Party to launch his own cross-party group, the Alliance for an Assembly, with Donald Dewar, Glasgow Garscadden, of the Labour Party, Russell Johnston, Inverness, of the Liberal Party, and Malcolm Rifkind, Edinburgh Pentlands, also of the Conservative Party. The Liberals and Communists contributed to both cross-party campaigns at the local level, but did not launch their own. Scotland Says Yes, in line with the nationalist campaign, also campaigned on what the Assembly would be able to do once established, for women, the social services, and education.

With all the campaigns launched in January, the questions of many undecided voters were would the Assembly lead to a breakup of the UK, would it mean more bureaucracy and more government, and would it cost more. Though the question of whether devolution would lead to a breakup of the UK was a difficult one with the various Yes campaigns holding various views on the matter, most of the Labour Yes campaigners adopted the rhetoric of it offering a greater say by Scots in their own affairs thus negating the need for independence, though not the same bombastic phrasing as George Robertson the view was the same. The basic statement that an Assembly would cost more and mean more bureaucracy was met with the argument that by controlling the bureaucracy the Assembly would be able to reduce cost. In addition to confronting these issues head on, the Yes campaign also campaigned strongly on the democratic argument that the Assembly would make Civil Servants in the Scottish Office more accountable and more responsive to public opinion.

The Yes campaign was also helped by the party-political broadcasts, of which three were in favour of devolution (Labour, Liberal, and the SNP) were in favour of devolution and only one (Conservative) was opposed. An attempt by the No campaign to stop the Church of Scotland from issuing a pastoral message in favour of devolution was only stopped when it turned out many ministers had already read the message; the Church had been a long supporter of devolution and it was further felt that to not issue the message would have been contradictory to their established position.

No Campaign

The No campaign was slightly less fragmented than the Yes campaign, consisting of Scotland Says No and Labour Vote No. Though the campaigns did not formally cooperate, there was not the same level of disagreement as there was between the Yes campaigns – at least one member of Labour Vote No, Robin Cook, would appear on a Scotland Says No platform. Scotland Says No also attempted to avoid duplication of effort by leaving some campaigning efforts to the labour Vote No, to the extent of keeping a record of their meetings and providing information on them when asked.

Scotland Says No was an organisation that dated back to 1976 under the previous names of Keep Britain United and Scotland is British, eventually rebranding as Scotland Says No in November 1978. Its leading lights including Iain Sproat, Aberdeen South, a Conservative, Baron Wilson of Langside, of the Labour Party, the Very Rev Andrew Herron, former Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. It also included the support of organisations such as the Confederation of British Industry and some Chambers of Commerce. The support of management organisations donated money and distributed No campaign material – some firms put them in employees pay packets. However, Scotland Says No was hindered by the Labour Movement Yes Campaign having a virtual monopoly on well-known names, and were unable to dictate the issues on which the campaign was to be fought.

Labour Vote No was chaired by Brian Wilson, the Labour candidate for Ross and Cromarty in the October 1974 election. It enjoyed some success in persuading local activists to not take part in the campaign, but after encouragement by the Party leadership for members to campaign for either side it found that those who would be in favour of a No vote were much less enthusiastic about campaigning than those in favour of a Yes vote. They were also unsuccessful in persuading the Party to adopt two party political broadcasts for each campaign, after previous attempting to have the Court of Session stop them entirely. The most fervent anti-devolution campaigner for Labour Vote No was Tam Dalyell, West Lothian, though the leadership underestimated him he addressed an unprecedent number of meetings during the campaign.

Though the Conservative Party did not launch its own official No campaign, as desired by Teddy Taylor, Glasgow Cathcart, it did take part as a supporter of Scotland Says No. This was to allow members in favour of devolution to campaign with their consciences. Though devolution was still technically Conservative Party policy they knew that a No vote would severely damage the Labour government, possibly even to the extent that the SNP would withdraw support for the government. To this extent several members of the Shadow Cabinet, including the Leader of the Opposition, appeared on platforms for Scotland Says No to campaign in the referendum. This was against the wishes of Teddy Taylor, who rightly predicted the appearance of too many English politicians would have the opposite effect on the No campaign than what was desired. The Conservative Party took the wrong lesson from these failed interventions, and late in the campaign they failed to convince Lord Home, the former Prime Minister, to speak out against the Assembly. Believing that any Conservative politician would hinder the efforts of the No campaign as opposed to just English Conservatives.

The No campaign fought part of the campaign on the fact the Assembly proposed by the Scotland Act would have no economic powers, with the main preoccupations of voters being prices and jobs it was thought any body that would not be able to deal with these concerns would not encourage voters reason for turning out. They also enjoyed some late success when several Yes campaign speakers, principally Jim Sillars, began to dwell at length on the unfairness of the Cunningham Amendment, the finances of Scotland Says No, and the appearances of English Conservative politicians. Despite this, by the time the polls closed on 1 March 1979, Scotland had voted in favour of the Scotland Act 1978 – but there was still the question of would it be enough to meet the requirements of the Cunningham Amendment?

Results

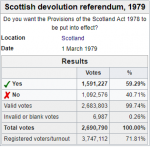

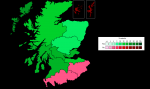

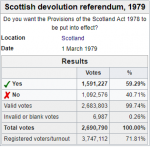

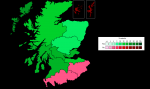

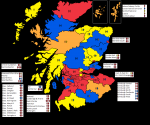

Polls in 1978 showed 60% in favour of devolution against 20% against; the referendum in 1979 showed these to be only half-right. 1,591,227 voted in favour of the Scotland Act, representing 59.29% of valid votes; compared with 1,092,576 voting No, representing 40.71% of valid votes. 3,747,112 voted in total, representing 71.81% of the total registered voters in Scotland. By less than 2,000 votes, the requirements of the Cunningham Amendment had been met.

With four exceptions, every region of Scotland voted Yes. The two regions bordering England, the Borders and Dumfries and Galloway, both had no majorities of less than 5%. The results in the Orkney and Shetland Islands, both voting by more than 30% against the Scotland Act being implemented, were reflective of the very different campaign fought their compared with the rest of the country. Both of the northern isles wanted a constitutional convention on their status within the UK, some seeing the crown dependencies of Guernsey, Jersey, and Mann as a model for themselves. They had at one point been promised one should a Scottish Assembly be set up. With all the political manoeuvring on the Scotland Act during its committee stage there were many in the Orkney and Shetland islands who were unsure if they should vote Yes or No to get the Commission.

The Labour government accepted that the requirements of the Scotland Act had been met, and that therefore devolution would be introduced for Scotland. This was not without acrimony from either side. Some proposed that the four regions that voted no be left out from the remit of any devolved Assembly – this brought harsh laughter from several Northern Irish MPs. The SNP and the SLP seemed to argue constantly that since the Assembly was not set up instantly after the referendum result that the government was reneging on its promises. The more pressing concern for the Labour government was the general election due in October, as the first elections to the Assembly were to come in 1980, by first-past-the-post in two or three-member seats based on the current Westminster constituencies. By the time the first elections to the Assembly were held there would be a knew Prime Minister, and she would have a long history of mutual incomprehension with the devolved legislature.