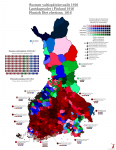

In 1916, Finland held its last elections under the rule of Grand Prince Nicholas II (better known outside of Finland as Nikolai II, Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias). It was also the only election held under universal suffrage in Finland that returned a one-party majority, in this case for the

Social Democrats. Although Finland didn't fully participate in the Russian war effort, being exempt from conscription and protected from its local defence forces being sent outside Finland without the Senate's consent, the privations of life during a world war nonetheless made themselves felt, and by 1916 the Finns were just as sick of it as their Russian neighbours. The SDP's big victory came after several years of growth, aided by the short and unpredictable election cycles that were the result of the Diet constantly getting into conflict with the administrators appointed from Saint Petersburg who had the power to dissolve it.

The politics of 19th century Finland had been divided into two broad factions within the ruling class: the

Svecomans, who wanted to maintain the traditional ruling elite and the Swedish language as a way to tie Finland more closely to the Germanic world, and the

Fennomans, who sought to make Finnish the official language of the state and promoted the universal teaching of Finnish culture. The Russians gave tacit support to the Fennomans early on, seeing in them a way to break Finland off from Sweden culturally and thus reduce the risk of Sweden trying to reclaim its former province, and along with the robust Finnish-speaking majority everywhere but the coastal regions and the cities, this gave them the clear upper hand from about the 1860s onwards. The Svecomans switched tactics as a result, moving from defending the dominance of the Swedish language and culture to protecting the Swedish-speaking minority. Among other things, this meant giving the rural Swedish-speaking populations in Nyland and Ostrobothnia a look-in for the first time in decades, and promoting their traditional culture as a counterpoint to the Finnish national romanticism of the Fennomans. When universal suffrage was granted in 1906, the remaining Svecomans formed the

Swedish People's Party (

Svenska folkpartiet,

SFP) as a way to advance the interests of all Swedish-speakers, and this essentially remains their function to this day.

By this point, the Fennoman movement was itself falling into discord. The loosely organised

Finnish Party (

Suomalainen puolue,

SP) lost the support of Saint Petersburg as soon as it became clear that it was in a dominant position, and under Alexander III, the policy of the Russian government switched from supporting Finnish culture to Russification. In 1894, the Finnish Party split in half, with a younger generation of politicians demanding a harder line against Russia and support for immediate moves toward independence. This group formed the

Young Finnish Party (

Nuorsuomalainen puolue,

NSP), taking its name by analogy to groups like Young Italy and Young Ireland, and quite soon a regional dichotomy emerged with the more socially stratified west supporting the "Old" Finnish Party and the more egalitarian east supporting the Young Finns.

The truly intense period of Russification started in 1899, after Nicholas II appointed Nikolai Bobrikov to the position of Governor-General of Finland. Bobrikov's instructions included reforming the Senate (the combined supreme court and main governing body) to bring it under tighter Russian control, introducing Russian as an official language and curtailing Finland's military autonomy, which brought such intense resistance that the period between 1899 and 1905 is known in Finnish history as the "Years of Oppression" (

sortovuodet/ofärdsåren). Bobrikov's rule only ended in June 1904, when a young nationalist named Eugen Schauman assassinated him. Schauman killed himself immediately after killing Bobrikov, which made him an instant national hero - in 2004, he was voted the 34th greatest Finn in history in a nationwide poll conducted by Yle. Russification further cemented the divide in the Fennoman movement, as the Old Finns supported appeasement, arguing that to resist openly would invite the Russians to dismiss all remaining Finnish officials and replace them with Russians, while the Young Finns continued to favour resistance.

After the 1905 revolution in Russia, however, the authorities eased off the Russification programme and allowed direct elections to a unicameral Finnish parliament, which would continue to share power with the Senate. These elections were open to all adult Finns regardless of sex, which made it one of the first countries in the world to give women the vote (depending on your definition of "country"). This meant that the Finnish parties would have to stake out economic policies as well as cultural ones, which proved somewhat awkward for the Young Finns in particular. The Old Finns were largely paternalist conservatives, who were sceptical towards a complete free market as well as expanding workers' rights, but the Young Finns found themselves split between a conservative and a liberal faction. The "swallows" (

pääskyt), led by the high court judge Pehr Evind Svinhufvud, supported a traditional social order as well as strict constitutionalism and resistance to Russian commands, while the "sparrows" (

varpuset), led by civil servant and law professor Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg, supported liberal reforms. This division would become completely untenable once Finland won its independence, which is why you don't see the Young Finns around today, but in 1916 the threat of Russification was still present enough that the party kept itself together.

The SDP emerged onto the scene around the same time, closely tied to the trade unions and associations of smallholders in the countryside - Finland was still overwhelmingly rural and agrarian at this time, but because it was also extremely poor, socialism held appeal for a lot of Finnish peasants. Like most social democratic parties of its day, it was modelled on the SPD in Germany, and like the SPD, it included elements ranging from moderate social reformers to outright revolutionaries. But like its bourgeois counterparts, the SDP was held together by its struggle against an outside enemy - though whether that enemy was the Russian autocrats or the Finnish bourgeoisie was very much in the eye of the beholder.

They weren't the only social movement to take root in rural Finland at this time, though, and really we'd be remiss not to talk about the

Agrarian League (

Maalaisliitto,

ML). The Finnish Agrarians differ from their Swedish and Norwegian counterparts in that they had one clear early leader and ideologue: Santeri Alkio, a writer and former Young Finn from Ostrobothnia who left the party after concluding its ideology was too far out of step with the needs and interests of rural people. Alkio took a great interest in the education and self-improvement of the peasant class, while also opposing and fearing the growth of socialism in rural Finland - this led him to formulate an ideology that very closely resembles political Catholicism, only without the clericalist aspects (although Alkio was a devout evangelical Christian, he opposed the established church). The Agrarian ideology was focused around decentralisation, community self-improvement and self-organisation, and social and economic reforms to improve the lives of the peasants. Alkio also supported independence and democracy, generally following the Young Finn line on those issues while continuing to stress the importance of rural people organising themselves rather than following the dictates of Helsinki intellectuals. In time, the Agrarians would become one of Finland's natural governing parties, being in power from independence until 1987 with only a few interruptions, none longer than two years. It took them a while to gain traction though, and in 1916 they were the second-smallest party in the Diet, beating only the incoherent and faction-ridden remnant of the

Christian Workers' League (

Kristilinnen työväen liitto,

KTL), which had once had ambitions of rivalling the SDP but now held only a single seat in Finland Proper.

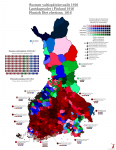

The Diet elected in 1916 would serve for about a year and a half, sitting through the fall of Nicholas II in the February Revolution and the collapse of the Russian war effort under the Provisional Government, but met its end when it passed a law transferring all political power except foreign affairs and defence to its own jurisdiction, which caused the Provisional Government to order its dissolution. Although not all Finns agreed that they were still able to do so, early elections nevertheless went ahead in October. By then, events were coming to a head in Russia once again...